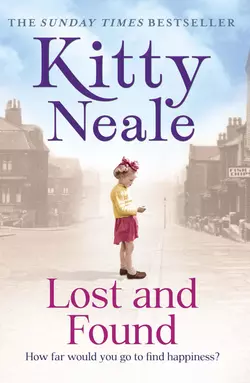

Lost & Found

Kitty Neale

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 384.72 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The gritty new drama from the Sunday Times bestselling author of Nobody’s Girl.Bullied by everyone around her for years, has Mavis Jackson finally found happiness? Or is it a case of going from the frying pan straight into the fire?BULLIEDTaunted by everyone around her, including her mother Lily, 15-year-old Mavis Jackson is devastated when her only ally, her father Ron, leaves home to beat his gambling addiction. Forced to walk the streets in search of junk to sell, the future seems bleak.BRIBEDUntil an unexpected fairy godmother arrives in the form of Edith Pugh. Struck down with a debilitating illness, she needs help around the home. In Mavis, she sees the perfect solution. Especially as she has ulterior motives…BLAMEDMeanwhile, Ron has fallen off the wagon and disappeared. Best mate Pete doesn′t know where he is and has to break the terrible news. But does he have another reason for his sudden interest in the Jackson family?BETRAYEDBack at Edith′s, Mavis revels in her new job. But when Edith reveals her true motives for taking Mavis under her wing, she faces a monumental decision, one which could change her life for ever…