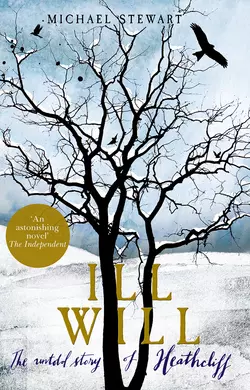

Ill Will

Michael Stewart

‘An astonishing novel’ The IndependentI am William Lee: brute; liar, and graveside thief.But you will know me by another name.Heathcliff has left Wuthering Heights, and is travelling across the moors to Liverpool in search of his past.Along the way, he saves Emily, the foul-mouthed daughter of a Highwayman, from a whipping, and the pair journey on together.Roaming from graveyard to graveyard, making a living from Emily’s apparent ability to commune with the dead, the pair lie, cheat and scheme their way across the North of England.And towards the terrible misdeeds – and untold riches – that will one day send Heathcliff home to Wuthering Heights.

MICHAEL STEWART is from Salford but is now based in Bradford. He has won several awards for his scriptwriting, including the BBC Alfred Bradley Bursary Award. His debut novel King Crow was the winner of the Guardian’s Not the Booker Award. Ill Will is his latest novel.

Copyright (#ulink_577f48a0-6b53-5582-a7dd-efc04cce932d)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Michael Stewart 2018

Michael Stewart asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008248178

Version: 2018-09-17

For Lisa and Carter

Contents

Cover (#u7d48bea7-1d42-5e12-ac1d-7f01cc1464c3)

About the Author (#uddca71ce-e4e8-5f49-b985-446bff72ecc2)

Title Page (#u4b5fb0a8-2f4e-5aaf-b63e-e48352c18d08)

Copyright (#ulink_eeaf6de5-5da2-5906-834b-c4cf6ef57b8f)

Dedication (#u03d4700f-646e-563c-baed-6e72ea21ce78)

1780 (#ulink_0aaac624-bf62-54b8-a745-b93ceaf27cd6)

On the Straw with the Swine (#ulink_ba0164cc-f1b1-5df3-9a64-385770ca5dbe)

Flesh for the Devil (#ulink_d313e6a4-7023-521b-a7d0-fb9bcfae3540)

The Man with the Whip (#ulink_402c8af3-a3d7-579d-9145-3ee2c420953c)

Throttling a Dog (#ulink_06b0f3ee-7929-5176-8ab1-3eff49952f8d)

Conjuring the Dead (#litres_trial_promo)

Tripe and Black Pudding (#litres_trial_promo)

In the Shadow of the Gallows (#litres_trial_promo)

A Game of Skittles (#litres_trial_promo)

Jonas Bold (#litres_trial_promo)

Pierce Hardwar (#litres_trial_promo)

Penny Buns and Jew’s Ears (#litres_trial_promo)

Humility, Cleanliness and Pure Thinking (#litres_trial_promo)

The Man with One Hand (#litres_trial_promo)

Vying the Ruff (#litres_trial_promo)

1783 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1780 (#ulink_658cd1e0-64ad-5f43-873e-c187fbae5c20)

You are walking through Butcher’s Bog, along the path at Birch Brink. Traipsing across Stanbury Moor, to the Crow Stones. A morass of tussock grass, peat wilderness and rock. There are no guiding stars, just the moaning of the wind. Stunted firs and gaunt thorns your only companions.

Perhaps you will die out here, unloved and unhomed. There was the tale of Old Tom. Last winter, went out looking for a lost lamb. Found a week on, icicles on his eyelids, half-eaten by foxes. Or was it the last wolf said to roam these moors? The ravens will eat out your eyes and the crows will pick at your bones. The worms will turn you into loam. You’ve forgotten your name and your language. Mr Earnshaw called you ‘it’ when first he came across you. Mrs Earnshaw called you ‘brat’ when first she took you by the chuck. Mr Earnshaw telt to call him Father and Mrs Earnshaw, Mother, but they were not your real parents. Starving when they took you in. They named you after their dead son. The man you called your father carried you over moor and fell, in rain and in snow. When finally you got to the gates of the farm it was dark and the man couldhardly stand. He took you into the main room and plonked himself in a rocker. By the fire you stood, a ghost in their home. Next to you a living girl and living boy, who spat and kicked. This was their welcome to your new hovel. Nearly ten years ago now. You’d spent weeks on the streets, eating scraps from bin and midden. Kipped by the docks and ligged in doorways. You’d trusted no one, loved no one, believed in nothing.

It was tough in the new place but you’d had it worse. You’d almost died many times. You’d been beaten inside an inch of your life. Gone five days without food. Slept with rats and maggots. Nothing this new place had in store could harm you more than you’d been harmed before. Or so you thought. The girl was called Cathy, the boy Hindley, and you hated them apiece.

Almost ten years ago. But you can still feel her hot spit on your face, and his boot in your groin. None of it ever hurt you as much as her words. Words that cut to the bone. Words that stab you in the back.

You stand on top of the Crow Stones on the brink of the wilderness. It is said that the stones were used for ritual sacrifice. The slit throat of a slaughtered goat. The gushing blood of a lamb seeping into the craggy carpet beneath your feet. The wind tries to blow you off your perch. Blow harder. You are the goat, the lamb, you care not for sacrifice. Let them take you. Let them bleed you. Fuck the lot of them.

For two years your adopted father tried to protect you from Hindley. From his maniac beatings, with fist and boot and club. Sometimes it worked. Until your adopted mother died and your father retreated into himself. The jutting stones of your borrowed home were fitting symbols. The grotesque carvings and crumbling griffins were your companions. But not now. Walking without direction. It doesn’t matter where you go as long as you go away from that place of torture, that palace of hate.

They called you dark-skinned gypsy, dirty lascar, vagabond, devil. You’ll give them dark, dirt, devil. Cathy wanted a whip. Hindley a fiddle. You’ll give her whip, him fiddle. You took a seat at the end of the hearthstone. Petted a liver-coloured bitch. There was some warmth in the room and it came from an open fire. Flames that licked, peat that steamed, coals that glowed, and wood that hissed.

Hindley called you dog and beat you with an iron bar. Mr Earnshaw tried once more to stop him. He sent Hindley to college, just to get the maniac away. And things picked up for a while. Then you watched your father die, watched the life drain from his eyes, his last breath leave his lips. You knelt at his feet and wept. You held onto his lifeless hand, the skin as brittle as a wren’s shell. Cathy wiped the tears from your eyes. Hindley came back from the funeral with a wife. She was soft in the head and as thin as a whippet. Always coughing her guts up. Things got bad again. Banished from the house, set to work outside, in the pissing wind and whirling rain. You were flogged, locked out, spent your evenings shivering in a corner while that cunt stuffed his face, supping ale and brandy. Eating and drinking, singing and laughing with his slut.

The wind has lulled now and you listen to its hush. You hear a fox scream and an owl cry. The night gathers in pleats of black and blue. The cold rain falls. You teeter on the brink. It would be so easy to tumble and smash your skull on the rocks. Let the life bleed out of the cracks and let the slimy things take you. No one would miss you. Not even you. The only thing that is real is the hardness of the rock and the pestilent air that festers. You could dive head-first onto the granite. Dead in an instant. Released from the teeth of experience.

You remember another night as black as this. Your love had lost her shoes in the bog beneath Whitestone Clough. You crept througha broken hedge, groping your way up the path in the dark, planting yourselves on a flowerpot, under the drawing-room window. They hadn’t put the shutters up and the light poured out. You clung to the ledge and peered in. It was carpeted in crimson and there were crimson-covered chairs. A shining white ceiling fretted with gold. A shower of glass drops hanging on silver chains, shimmering. It was Edgar and his sister Isabella. She was screaming, shrieking as if witches were ramming red-hot needles in her eyes. Edgar was standing on the hearth weeping. In the middle of a table sat a little dog, shaking its paw and yelping. They were crying over that dog, the silly cunts. Both had wanted to hold it and neither had let the other do so. You laughed, you and Cathy. They were like toy dogs themselves, all prim and prettified. Milksopped and mollycoddled.

They stopped yelping. They must have heard you laugh. Then Edgar saw you at the window and started shouting. You ran for it, but they’d let the bulldog loose, a big bastard with a big bastard head, and it had got Cathy by the ankle. It sank its bastard teeth in and wouldn’t let go. You got a stone and thrust it between its bastard jaws, crammed it down its bastard throat, throttled that bastard dog with your bare hands. Its huge purple tongue was hanging half a foot out of its mouth, and blood and slaver dripped from its lips.

Then there was a servant running towards you. A big bear of a man. He grabbed Cathy and dragged her in. You followed him. Mr Linton was running down the hallway, shouting ‘What is it?’ The man grabbed you inside too and pulled you under the chandelier. Mr Linton was looking over his spectacles. Isabella said, ‘Put him in the cellar.’ ‘That’s Mr Earnshaw’s daughter,’ said another. ‘Her foot is bleeding.’ You cursed the servant, swore like a trooper. He dragged you into the garden, threw you on the grass, then went back to the house and locked the door behind him.

You went to the window again. Thought about smashing it in. She was sitting on the sofa. A servant brought a bowl of water. They took off her shoes and stockings. They washed her feet. They fed her cake. Edgar stood and gawped. They dried her wild hair and combed it sober. They wheeled her to the fire. The Lintons stood there staring.

You should shelter. Soaked to the bone and shivering, teeth chatter in your skull. You think about a nook beneath Nab Hill where the earth is soft and the rocks block the wind. It was the first place you and Cathy fucked. She took hold and put you inside her. Her white thighs astride your black hips. Your teacher, your lover, your sister, your mother. She was all you needed in the world. The rest could go to hell.

She stayed at Thrushcross Grange for five weeks. Till Christmas. Hardly knew her when she returned. Turned up on a black pony, hair all done, wearing a fancy hat with a feather in the ribbon. Even her speech was altered. She was dressed in a silk frock. You felt ashamed of your appearance, felt dirty. Your hair was coarse and uncombed. She said you looked grim and laughed in your face. You couldn’t stand to listen to that laugh, couldn’t stand to be so black next to one so white. You ran out of the room, burning with shame. Your flesh was a fire of disgust. The next day the Lintons were invited to the house. You were banished to the outbuildings. They called you dog, called you devil. You’ll give them dog, give them devil.

Your thoughts are jumbled. They whirr like the storm around you. They make a flaysome din in your skull. Shelter. There’s a cave under Penistone Crags. A roof over your head. A hole to lig in. Get out of the storm. Where are you? Somehow you are lost. The moor so familiar, but you don’t recognise the landscape. You make out black shapes, skeletal outlines of withered hawthorns. Whinstone and mud. The ground keels. You are somewhere. You are nowhere. You are here. The night is as black as your shame, as black as your face. You are wandering like a blind man. You don’t know anything any more. Not what’s up. Not what’s down. You don’t know who you are, where you came from. You don’t even know your own name.

On the Straw with the Swine (#ulink_cfb50fb9-5576-51ad-b307-2e9af50b2ea4)

I woke the next morning with my head on a pillow of mud, Cathy. I could hear the worms crawl through the earth beneath. I imagined them poking their blind noses through the loam. I ached all over. Every bone was a bruise. Everything I touched and everything around me was cold and wet. I watched an ant crawl over the back of my hand, clambering over each hair as though it were a hillock. It was a bright June morning. The sun was shining, making the dew glisten. I stood slowly, painfully, and looked around. I recognised where I was. Somewhere between Harbut Clough and Shackleton Knoll. Not far from the prominent stoop where you first kissed me on the lips. Lips so soft. Kisses so sweet. The lark and the linnet sang to us.

I walked along a faint path, past Lumb Falls, towards Abel Cross. My head was pounding and my mouth was parched. My eyes stung and my legs throbbed. I was shivering. I picked up pace. Got to gather heat. I walked past a cluster of farmhouses and stone outbuildings. By a mistal I could hear the milch cows lowing inside. Maybe they would let me have some barley bread and buttermilk. No, got to keep on going. I contoured over the hillside, Crimsworth Dean in the distance. The forest beneath, a verdant roof of leaves. I could see at the top of the woods the outline of Slurry Rock jutting out like a boar’s fang. I walked along the grassy bank of the beck until it sloped gently down to the water. I stooped to drink where the flow was strong. I let the cold of the water flurry in the cup of my hands, then supped greedily. My mouth and throat unclagged as the cool liquid slooshed.

I could live out here, a wild man in a cave. I didn’t need anyone else, want anyone else, have anyone else. I could catch rabbits with snares I’d make myself and cook them on the fire. I could make a rod out of willow and fish for trout and pike. I could make a bed out of fresh heather and, like the titmouse, I’d gather the soft heads of cotton grass to line my nest. Fuck people, I didn’t need them. People only brought you pain. Better to stay away from people. At least until I had a plan.

I thought about you with the Lintons that day, when they came to visit. I vowed to get you all or die attempting it. Supping mulled ale from silver mugs. I was a stain on their polished tray. I was the muck on their well-scrubbed floor. Leave them to it. I had turned my back on them and gone inside to feed the beasts. Fuck ’em. Fuck the rotten lot. Spoke to no one except the dogs. And when you had all gone to church, I went onto the moor. Fasted and thought. I had to turn things around. I had to get you back.

I came in through the kitchen door, went to Nelly and said, ‘Make me decent.’ I was younger than Edgar but taller and twice as broad. I could knock him down in a twinkle. I wanted light hair and fair skin. Nelly washed and combed my curls. Then she washed me again. But she couldn’t wash the black off my face. Then I saw you all, descending from a fancy carriage, smothered in furs. Faces white as wealth. I’ll show the cunts, just as good as them, and I opened the door to where you and they were sitting. But Hindley pushed me back and said, ‘Keep him in the garret. He’ll only steal the fruit.’ How ashamed I’d felt that day. How cold and lonely I’d been in that garret with just the buzzing of the flies for company.

I stopped by a ditch and picked some crowfoot. I looked at the white petals and the yellow centres. Some call it ram’s wort; it is said to cure a broken heart. How pretty it looked with its lobed leaves, and how desolate. I crushed it up and threw it on the ground. I had no use for pretty things. Bring me all that is ugly and I will serve them all my days, the henchman to all that is loathsome. I laughed at my own grandiosity. What was I? Even less than the muck on my boots. Which weren’t even my boots, but Hindley’s hand-me-downs. How he’d gloated over that. Another detail he could use to show the world that I was beneath him. Almost everything I owned had once been his property. I had nothing that I could call mine. Not my breeches nor my surtout, not even the shirt on my back. I walked a little further through grass and moss and rested by a rowan tree. It is said that witches have no power where there is a rowan tree wood. Do you hear me, Cathy?

My mind snapped back to that day. That cunt Edgar had started, saying my hair was like the hair of a horse. I’d grabbed a bowl of hot sauce and flung it right at him. Edgar had screamed like a girl and covered his face with his hands. Hindley grabbed hold of me, dragging me outside. He punched me in the gut. When I didn’t react, he went for the iron weight and smashed it over my back. Go down. Kicking me in the ribs. In the face. Stomping on my head. Then he got the horse whip and flogged me till I passed out.

I gripped the root of the rowan to help me to my feet. I needed something to eat to stop the pain in my gut. I saw some chickweed growing by a cairn and clutched at the most tender stems. It tasted of nothing. I found some dandelions further on and chewed on the leaves. They were a bitter breakfast. I carried on walking. Something of the plants must have nourished me because as I walked I could feel some of my strength restored. The sun was getting bigger and higher in the sky and my wet clothes began to steam.

Cold stone slabs. When I had woken the next day from Hindley’s flogging, Cathy, I discovered that he’d locked me in the shed. I was aching all over, bruises everywhere, caked in dried blood. It wasn’t the first time he’d beaten me senseless, nor was it the first time he’d shoved me in the shed. I could cope with the beatings, and the cold stone flags for a cushion, but the humiliation still stung like a fresh wound. A razor’s edge had a kinder bite. I could hear you and them in the house. There was a band playing, trumpets and horns, clatter and bang. I could hear you and them chatting and laughing as I lay in the dark, bruised and battered, my whole body a dull ache and a sharp pain. I swallowed and tasted the metal of my own blood. How to get the cunt? I didn’t care how long it took. I didn’t care how long I had to wait. Just so as he didn’t die before I did. And if I burned in hell for all eternity it would be worth it. At least the flames would keep me warm and the screams would keep me company. Kicking the cunt was not enough. He must suffer in every bone of his body and in his mind too. His every thought must be a separate torture. He must have no peace, waking or asleep. His whole life, every minute of every hour of every day, must be torture. Nothing less would do.

I’d been walking for a good hour and my clothes were almost dry. I’d walked off the stiffness and the pains all over my body were abating. But not the pain in my head. That was growing. I walked through Midgehole and along the coach road to Hebden. I’d walked it before, once with my father and several times with Joseph. With horse and cart. I was hungry again and thirsty. The chickweed and dandelion breakfast not enough to sustain me for long. I hadn’t eaten a proper meal since yesterday morning, and only then a heel of stale bread with a bit of dripping. Along the roadside was a row of cottages. Sparrows flitted from the ivy to the hedges. A cat sat and watched. The world was waking up. I saw a man load up his horse and cart with woven cloth and earthen pots. It was market day then. Rich pickings for some. Perhaps there would be opportunity to work for some food or like the vagabond you all think I am, I might find a way to steal some victuals.

By the time I got into town, the market was already open. Merchants stood by their stalls. Some of them shouted their wares. Others made a show of their articles. There were ’pothecaries selling cure-alls, potions for this, creams for that. There were herb sellers. Grocers standing by stalls piled high with fruits and vegetables. Some sold meats: hunks of hams, racks of rumps. Others sold cheeses: wheels and wedges, finished with mustard seeds and toasted hops. Baskets, breeches, a brace of grouse. Hats, shawls, second-hand wigs, a heap of dead rabbits. Cordials and syrups, jams and sauces. Woollens from the hill weavers. Pewter dishes, earthen plates, porridge pots and thibles. I could smell lavender, thyme and burdock, and other sharp smells I couldn’t discern. The stallholders shouted over each other, so that you couldn’t make out what they were saying, just the bark and screech of their voices. Did I want this? Did I want that? A quart for a quarter. Four for a penny. Half for ha’penny. I didn’t want much. A lump of cheese or a slice of beef would do me. I wandered around, waiting for my opportunity, but there were too many eyes about.

I bade my time before I found a way to swipe an apple. I tucked it under my coat and walked off, waiting until I was around the corner before I took a bite of the sweet flesh. The apple was wrinkled by winter but to me it tasted delicious. As I took bite after bite of the fruit, I wondered if my revenge would taste as sweet as that ripe pulp. I watched children laiking. They ran after a ball around the town square, playing catch, then piggy-in-the-middle. A small child squealed as the older taunted him. I remembered playing piggy-in-the-middle with you and Hindley. He’d always throw the ball too high for me to catch, even if I jumped. But you would throw it low on purpose and pretend it was a bad throw. From those outward actions, our inner feelings grew.

I thought back to the day his slut gave birth to a son. She was ill, crying out in pain, and it was such joy to watch Hindley suffer. That week, as she lay dying, the cunt was in agony. How I laughed behind Hindley’s back. Thank you, God, I said under my breath, or thank you, devil. I’d prayed to both, not knowing which would hear me first. All my prayers were answered. I knew what Hindley loved the most and it was his slut. I knew what would hurt the cunt the most – the slow, painful death of his slut.

The doctor’s medicine was useless. My spell was stronger. I learned from your witchery and from your arcane power. My anti-medicine had worked. I watched her cough and splutter. I watched her chuck up blood. I watched the life drain from her face. I watched the wretched slut die in front of the cunt. I went to the funeral so I could observe his agony some more. How I’d wanted to laugh when they’d lowered the coffin into the ground and tears had rolled down his cheeks. Each tear was a sugared treat. And afterwards in the church hall, he was inconsolable. The curate had patted him on the back, said he was sorry for his loss, and offered him some brandy. But Hindley was unreachable in his grief. Only I knew how to reach him. Later that night I’d put my ear to his chamber door and listened to him sob as though it were sweet music.

Hareton was the bairn. The fruit of Hindley and the slut’s union. You were fifteen, all curves and skin. I taunted Hindley so that he beat me. Called his bairn a witless moon-calf. And I laughed when he fired and lost his temper. So that his beating brought no satisfaction. Fuck the lot of them: Isabella, Edgar, Hareton, Hindley. I’ll make them pay. I’ll make them all suffer. I’ll make a purse from their skin. They called me vulgar, called me brute. But they had no inkling of the depths of my brutality. I spoke through gritted teeth: mock me now, but one day I will sup from your silver cup. And it won’t be ale I’ll sup, but a broth of your tears and blood.

I stopped a way from the market and watched women haggle with the stallholders. I gnawed the apple to its core, crunched the pips between my teeth, and slung it over a hedge. Truth was, I didn’t have any idea what to do next. I had no friends, no food, no money, no home. All I could trade was my labour. I didn’t want to work here in Hebden, too close to you and them. Even if I didn’t see you, or Joseph or anyone else, word would get back. I needed to go further, to a new parish. A place called Manchester, halfway between home and Liverpool, where Mr Earnshaw had brought me from. We’d discussed it together after Sunday service one time. There was lots of work by. Big mills being built and new machines invented. We’d talked about how we could run away, find work and make a fresh start, free from Hindley’s tyranny.

I went back to the marketplace. More people were milling about now and it was easier this time to steal another apple and a chunk of bread. I stole a wheel of cheese and a meat pie, put them in my pockets. I climbed to the hill above the town. The sun was still in the east and I needed to walk west as that was the direction of Manchester. I just needed to keep the sun behind me until noon, then keep the sun in front of me till dusk. I could see Lumbutts Farm in the distance. I made my way across moor, through Bird Bank Wood and Old Royd. And eventually into the village of Todmorden. The road followed the river, where the houses were built into the steep clough, which climbed high on both sides. The effect of this was to make the way ahead darker than the way back. Parts of the clough were quarried and there were heaps of stones waiting to be faced at the mouths of the delves. I needed money and lodgings. I was far enough away now from Wuthering Heights. Although I’d walked here by myself before, when you were laid up at the Lintons’, I knew that it was far enough away from Wuthering Heights that I’d not be spotted here. Joseph said the men who lived hereabouts had hairs on their foreheads and the women had webbed feet, but I suspected that was just idle laiking. I could ask for work. Summer. Plenty of farm labour. It was midday when I arrived in the village. I sat down by the green. I ate the pie. First the crust, then the filling. I wandered around until I found a tavern on the corner of a cobbled street. There was a sign outside that I could not read, but the painting on the sign was of a jolly fellow in a bright smock, and the place looked friendly enough. After some deliberation, I plucked up the guts to go inside.

It was dark and smelled of stale beer, colder inside than out. There was a fireplace but no fire, it being the wrong time of year for flames. I marked the stone floor and the low wood beams, the wooden benches and seats. A few farmers were standing around a horn and rope, playing ring-the-bull. A group of labourers were leaning on the bar. I asked them to excuse me as I made my way to the barrels. They were in no rush to move but shuffled out of the way nevertheless.

‘What can I get you?’ said the landlord. A large, ruddy-faced man with ginger whiskers. He was standing by a massive barrel of ale, laid on its side, with a tap at one end. I had no money.

‘I’m looking for work.’

‘You what?’

‘I want a job.’

‘Round here?’

‘Or hereabouts. I’m a hard worker. I don’t shirk. I can do any amount of farm work: digging and stone-breaking, wall-building, graving, tending foul. Whatever there is I can turn my hand to it. Do you have work yourself? Cellar work, maybe? I can lift barrels all day.’

‘No. No work here, pal.’

‘Would you mind if I asked your customers?’

‘What do you think this is? Either buy some ale or fuck off.’

I looked around the room. At the hostile faces, white faces. White faces looking me up and down. I didn’t fit, wasn’t welcome. I looked at the labourers and saw the muck on their knuckles like ash keys. I looked at the farmers and saw the mud on their boots. Yes, there was work hereabouts, but not for me, Cathy. Turn around. Get out.

I wandered around the village. Not much to see. There were signs of life all right. But no life for me. I made my way to the river. If I followed its flow, it would take me in the right direction. There was a faint path by its banks, more of a rabbit run, or a badger track. I carried on walking, at the edge of what I knew. I’d never been further than this point. Not since I was a small boy, in any case, when I was taken from one place to another, then to somewhere else to be abandoned at the dockside. My memory of my early life was like a landscape shrouded in a thick mist. I remembered streets near water. I remembered rowing boats and ships with massive sails. I remembered a warm room full of strong smells and harsh sounds, a strange man with a knife, beckoning me. He was smiling at me but something about him was unsettling. He smelled of grease and sweat and his teeth were black. There were many shiny surfaces but everything else was a blur. I didn’t even have a clear memory of Mr Earnshaw. The first thing I remember clearly is you, Cathy. I remember our first meeting, and our friendship growing stronger each day. Until it grew beyond friendship into something else. I remember the first time we fucked, and after, lay in each other’s arms, looking up at the sky, watching the clouds form into faces. Counting crows. Joseph was out, loading lime past Penistone Crags. Hindley was on business. When we got back home, I marked the occasion in the almanac on the wall. A cross for every night you spent at the Lintons’. A dot for those times spent with me on the moor. I showed you the almanac. You said that you found me dull company. You said I knew nothing and said nothing. You said I stank of the stable. Then Edgar turned up, dressed in a fancy waistcoat and a high-topped beaver hat. I left you to your pretty boy.

As I followed the beck west, I dreamed as dark as the brackish waters. I wanted to kill them all, but like a cat with a bird, leave them half-killed, so I could come back later, again and again, to torment them. You as well, Cathy. You were not exempt from my plans. The sun was directly above me now and I could feel its heat. I took off my coat and bent down low so that I could cup some water from the beck. I saw my black reflection staring back. I took a drink. It cooled me. I sat by the bank and brooded. I watched water boatmen and pond skaters dance across the surface of the beck where it gathered and pooled. I watched beetles dive for food and gudgeon gulp. Blue titmouse and great titmouse flittered in the branches above. I watched a shrike impale a shrew on the lance of a thorn. I didn’t know how long it would take me to get to Manchester. Another day or two, perhaps. Surely there would be work there for a blackamoor. I’d heard we were more common in those parts. I stripped off and dived into the beck, washing all the filth from my body. The water was cool at first but as I swam, it soon warmed around me. My flesh tingled and my skin tightened. I splashed water on my face and rubbed at the mud in my hair. I lay back, let the water take my weight, and looked up at the sky. I floated like that, staring up at the white whirl of clouds, with no thought in my head. The clouds drifted, gulls flew by. I closed my eyes and tried to keep my mind as clear as the sky, pushing out all thoughts.

Across the blank blue of my mind I heard a voice: There’s money to be made in Manchester town. And I remembered Mr Earnshaw say that a man from humble stock could make a pretty penny in the mills and down the mines. And I heard your voice, Cathy. That it would degrade you to marry a man as low as me. Oh, I’d get money all right. I’d show you. I’d shame you. Words that burned. Words as sharp as swords. Words you could only say behind my back. I’d shove those ugly words down your lovely throat.

I swam to the bank and climbed out. I sat by the edge of the water and watched toad-polls flit by the duckweed and butterflies flap by Rock Rose. A butterfly and a frog. They both had two lives. Why couldn’t I have two lives? Like that toad-poll at the edge of the beck, already sprouting legs, about to break through the film of one world into another, I was on the cusp of the life that had been and the life that could be. I could rise from the depths. I could crawl into the light.

I lay naked as a newborn and listened to rooks croak and whaaps shriek. I let the sun and the breeze dry my skin, then I got dressed. I stuck my hands deep in my pockets, retrieved the rest of the pilfered vittles, just crusts and crumbs, and scoffed the lot. I lay back on the cool grass to rest for a minute or two. I watched twite and snipe, grouse and goose. I didn’t want to think about you or them but it seemed that my mind was set on its course. I couldn’t stop it thinking about them and you. What they had done. What they had not done. What you had done. What you had not done. It would degrade you. I would degrade you.

I watched the peewit flap their ragged wings and listened to their constant complaining, tumbling so low as to almost bash their heads on the bare earth. Perhaps they had young nearby and were warning me away.

Out here, surrounded by heather and gorse, with the blue sky above me, I felt free. I closed my eyes and felt the sun’s rays on my face. The sun felt like you. Like your heat next to my skin. Like your breath on my neck.

When I woke the sun was further on. I felt dozy. Must keep going. I got up and shook the grass from my clothes. I plucked cleavers from my breeches. I stretched my limbs and joined the path by the river once more. I walked through fields of sheep, fields of wheat, fields of beef. Fields of milk, mutton and mare. Over meadow, mire and moor. I climbed over dry-stone walls. And clambered through forest. Eventually I approached another village. I arrived at a packhorse track and walked along it. I passed cottages and barns. Mistals and middens. There was a sign on the road but I couldn’t read it. Although I knew the alphabet, you never completed your tutelage. There was always something in the way with language. We had a more direct connection, Cathy. A pure link. That’s what you said, and I believed you.

It was a small village with two taverns, a butcher’s, a baker’s and a chapel. All clustered around a green where a tethered goat grazed. I went into the first pub and asked for work. I went into the second pub and asked for work, and in every shop. Everywhere I enquired the answer was the same: no work for the likes of you. My limbs ached. My eyes felt as though they were full of sand. I sat on a bench in the graveyard. I was tired and it would be dusk soon. No roof to offer me shelter. I sat and watched two old women tend to a grave. They pulled out weeds and arranged some flowers. They scraped away the lichen from the engraving so that the chiselled letters were fresh once more. They nattered and gabbed. So-and-so has his eye on so-and-so. Will he do right by her or will he use her as his plaything? Looks Spanish. When’s summer going to start proper? Who was that strange fella in church last Sunday? Not seen him before. Not from these parts. Old Mr Hargreaves is dead. Finest weaver in the county. Found him in his own bed. Half-undressed. On and on they nattered, about this and that. By these women was an open grave.

The women noticed that I was watching them. They looked at me suspiciously. They pointed and whispered. But I didn’t care. Let them talk. Let them think and say what they liked. They meant nothing to me. There was no one alive who meant anything to me now. Not even you, Cathy. I was nothing, and no one. I focused instead on the black rectangle to the side of the women. Its blackness falling down into the ground. Where did it go, this blackness? To hell? Perhaps I should climb into this hole. I thought back to Joseph’s fire-and-brimstone catechisms. Was hell really all as bad as he would have it? With sinners in perpetual torment? You showed me a picture in a book, Cathy. A man with horns and a pitchfork and a big grin on his pointy face. He looked more comical than evil. Evil hides behind the door. It lurks in the shadows. As I thought about hell and evil, I saw people congregate. There were men and women gathering around the black rectangle. There were four men carrying a coffin on their shoulders. They were dressed in black and the men and women surrounding the hole were dressed in black. A veiled woman was crying. I could see her face shake beneath the veil and tears fall onto her dress. It was good to watch her cry and watch the rest of them grieve. Let her weep in her widow’s weeds. It was music and food to me.

I thought about her wedding to this corpse who had once been a man. Perhaps in this very church. Everyone done up again, only this time in white and brightly coloured garments, the lavish pretence, the gilded facade. Pretending to marry for love, when really it was for wealth and status. Love didn’t need a marriage chain or a poncey parade. Love baulks at ceremony and licence. They talk about tying the knot but love unties binds. It lets the bird out of the cage. The bird that is freed flies highest. The cage is best remembered enveloped in flames.

You told me you would never get married. That we would always be together. You promised. How easily your words betray you. Marriage is for dull people, we both agreed. And people are dull, except for when they grieve. I watched the priest and the party of mourners, watched the mound of earth at the back writhing with worms, starlings stabbing at the flesh. I watched the men drop the coffin, using ropes to lower it slowly into blackness. More people weeping. Some of them beyond tears. I supped on their misery. Every death is a good death. All flesh is dead meat. I had cried when Mr Earnshaw passed away, but now I wished I hadn’t. I was glad I’d listened to his last breath. Seen him choke. Will he go to hell or to the other place? I hoped he would burn and his blood would boil in the red flames of the inferno. I cursed cures and blessed agues. At last the wooden box was lowered into the ground completely and the ropes thrown in after it. Swallowed up by blackness. How long would the fine oak casket last until the wood splintered and decayed, and all the slimy things ate beneath the grave?

When all of the party had gone back the way they came, with heads bowed and handkerchiefs on display, I stood up and approached the open grave. I stood over the black hole and peered in. The coffin was surrounded by clay, with black soil on top of the box, which the pastor had chucked in. I imagined, in the place of the coffin, you and I, Cathy, lying next to each other. With six feet of earth above our heads. For all eternity. That way you would keep your promise.

I left the churchyard and wandered around the village and the looming moorland until it was fully dark. I was looking for shelter. I came across a farm surrounded by outbuildings. I found an unlocked barn, lifted the latch and swung open the door. Inside there were pigs, nudging and jostling each other. They smelled of their own shit. In the corner, by the swine, was some loose straw. It wasn’t exactly a four-poster bed but I could make my rest out of that, I thought.

I left the barn and wandered some more, not tired enough to lie down on God’s cold earth. I walked down a tree-lined track, back into the village. As I did, I heard music in the distance, a cheerful jig, and, drawn to the noise as a moth is to a lantern, I tried to find its source. I wandered along cobbled roads and muck tracks until I came to a village hall. It was a large barn, painted white, with light pouring from its windows. The music was coming from inside. I walked around the back. There was a small leaded window and I peered in. There were lines of lanterns and a huge fireplace with a roaring fire. There was a long table laid with food and drink. There were people lined up dancing: men and women of all ages. The women wore colourful frocks and bonnets. The men wore smart breeches, bright waistcoats and fancy hats. The hall was decorated with brightly coloured ribbons. There was a fiddle player in a cocked hat, playing a frenetic tune. I watched the group dance and sing and sup flagons of ale. I watched them smile and laugh and talk excitedly. The men held their women in their arms and drew them close to their bodies. I felt sick at the sight of them.

Then I saw a black, repulsive face staring back at me. Half-man, half-monster, just as Hindley said. My reflection in the glass pane. A black shadow of a man with not a friend in the world nor a bed to rest, barred from life’s feast. I wanted the night sky to swallow me up, to be dust. I could never be one of those people in there. My life would never be one of mead and merriment. Condemned to stand outside the party. Not like you, Cathy, with your fancy frocks and fancier friends. With your ribbons and curls and perfumes. I wandered back to the farm, crept into the animal barn, and lay down on the straw with the swine.

Flesh for the Devil (#ulink_a827ffe7-be88-5a87-b0d1-5b74f21f0613)

That night I dreamed we were on the moor; the heather was blooming, and you were teaching me the names of all the plants of the land: dog rose, gout weed, earth nut, fool’s parsley, goat’s beard, ox-tongue, snake weed. Your words were like a spell. I watched your lips form the sounds. I saw your tongue flit between your perfect teeth. Witches’ butter, bark rag, butcher’s broom, creeping Jenny, mandrake. We looked around at the open moorland, but it had all been hedged and fenced and walled. There were men, hundreds of them, burning the heather, digging ditches, breaking rocks. There were puritans, Baptists, Quakers, inventors, ironmasters, instrument-makers. Our place had been defiled. The flowers of the moor had been trampled on. The newborn leverets butchered. The mottled infant chicks of the peewit had been crushed underfoot. Guts in the mud. You were in the middle of the mob, a heckling throng, staring around. I held my hand out but I couldn’t reach you. You were lost to me.

The next thing I was aware of was someone taking me by the shoulders.

‘What the bloody hell do you think you’re doing?’

I was in the barn with the swine, and a lump of a man with a bald head was shaking me roughly. He wore big black boots and a leather jerkin. He looked more like an ogre than a man. It was morning and light from the open barn door poured in.

‘I’m sorry, sir.’

I was too weak from sleep to fight the brute.

‘What do you think this is, a doss-house?’

‘I had nowhere to stay,’ I said.

‘That’s no excuse.’

‘I was tired,’ I said.

‘Get up and get out. This isn’t a hostel for gypsies.’

‘I’m no kettle-mender.’

‘What’s your name?’

I thought for a moment; I wracked my brains.

‘Come on then, lad, speak up. Have the hogs gobbled your tongue?’

I remembered that young boy at chapel, Cathy, you were friendly with him. Died of consumption a few years since. I always liked his name. It was good and whole and clean.

‘My name, sir, is William Lee.’

I’d stolen the name of a dead child. A boy we laiked with before and after sermon.

‘Well then, William, Will, Billy, that doesn’t sound gypsy to me, I give you that. What kind of work can you do?’

‘I can dig, build walls, tend fowl, tend swine. Any work you have.’

‘Are you of this parish?’

‘I’m an offcumden, sir, from the next parish.’

‘I do need hands, as it happens.’

‘What for?’

‘I’ve a wall that needs building. And stone that needs breaking. A bloke did a flit after a drunken brawl a few nights back. I’m a man down.’

‘I’m that man, sir. I’m a grafter.’

‘Sure you’re not a pikey?’

‘I’m sure.’

‘I don’t employ gyppos.’

He took me over three fields, two of meadow, one of pasture, to where there was a birch wood and a small quarry. As we stood by the delph I realised, in fact, that he wasn’t as large as I’d at first thought. Though still heavyset and big of bone, he was not the giant my waking eyes had taken him for.

‘This is where you get the stone. There’s a barrow there. Don’t over-fill it, mind. I don’t want it splitting.’

He showed me where it had been parked for the night. Next to the barrow were several picks and wedges, as well as hammer and chisel. Then he walked me across to another field where a wall was partly constructed.

‘And this is the wall. In another hour or so there will be some men to join you. Some men to break stone and others to build. The one they call Sticks will tell you what to do.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

‘The name’s Dan Taylor. I own this farm.’

With that the farmer walked back down to the farm buildings and I sat on a rock. I amused myself by pulling grass stalks from their skins and sucking on the ends. I gathered a fist of stones and aimed them at the barrow. I watched the tender trunks of the birch wrapped in white paper. A web of dark branches. The leaves and the catkins rustled in the breeze. I waited an hour or two before the first of the men arrived. He was skinny as a beanpole and his hair was dark. He had a bald patch to the side just above his ear, in the shape of a heart. His beard grew sparsely around his chops. He told me the farmer had spoken to him about me.

‘Well, William Lee, you do as you’re told and we’ll get along fine, laa. The name’s John Stanley. Everyone calls me Sticks.’

He unfurled his arms the way a heron stretches out its wings and offered me his willowy hand to shake.

We broke stone for a time before two more men appeared and joined us. When we were joined by another two men, Sticks put his pick down.

‘Right, men, we’re all here and there’s lots to do. Looks like the weather will hold out despite the clouds.’

He pointed up. There were patches of blue but mostly the sky consisted of clouds the colour of a throstle’s egg. Not storm clouds though.

‘Good graftin’ weather,’ one of the men said.

‘This is William Lee. He’ll be working with us today. Me, William and Jethro will work here to begin. Jed, you barrow, and you two start walling. We’ll swap after a time. Come ’ed.’

We set to work again.

‘You from round here then, laa?’ Sticks said as he loaded up a barrow with freshly broken stones.

‘The next parish. About thirty miles east.’

‘So what brings you to this parish then?’

‘I’m just drifting. No particular reason.’

‘People don’t just drift. They always have a purpose. You’re either travelling to somewhere or running away from someone. Which is it?’

‘Neither.’

‘Suit yourself. Give me a hand with this.’

I helped him lift a large coping stone.

‘Had a southerner here last week. From Sheffield. Think he found us a bit uncouth. Only lasted two days. Could hardly tell a word he said, his accent was that strong.’

‘You don’t sound like you’re from round these parts yourself,’ I said.

He had a strange accent and not a bit like a Calder one. He had a fast way of talking and a range of rising and falling tones that gave his speech a distinctive sound.

‘You travel around and you take your chances. I’ve done it myself. Got turned out of one village one time. The villagers threw stones at me and called me a foreigner. It’s getting harder and harder for the working man to make a living.’

‘Why’s that then?’

‘Because a bunch of aristocrats are stealing the land beneath our feet. They’ll turn us all into cottars and squatters. Before you know it there won’t be any working men, just beggars and vagrants, thieves and highwaymen, prostitutes and parasites. Mark my words, laa.’

‘Is that so?’

‘The days of farm work is coming to an end. They’ve got Jennies now across the land that can spin eighty times what a woman can spin on her tod. A lot of the labourers hereabouts have gone off over to Manchester, doing mill work, building canals. I’ve done canal work myself, built up the banks, worked on the puddling. Dug out the foundations. It’s back-breaking work, I’ll tell you that. It’s said that on the duke’s canal the boats can travel up to ten miles an hour. And not a highwayman to be seen. Done dock work as well, in Liverpool. That’s where I’m from, you see, laa.’

I liked the way he pronounced ‘Liverpool’, lumping it up and dragging it out.

I thought about where I had come from. All that I knew was that Mr Earnshaw found me on the streets of that same town. Perhaps I would go back there. Seek out my fortune in that place instead. I wasn’t fixed. No roots bound me to the spot. Where there was money to be made that’s where I was heading. Enough money to get you and Hindley. If I were to make the journey, I could use Sticks’s know-how.

‘I’m heading that way myself,’ I said.

‘Be careful how you go, laa. It’s not safe to walk the roads. A man’s liable to be picked up by a press gang or else kidnapped and sent to the plantations. They’re building big mills over in Manchester. But you won’t get me going there. Worse than the workhouse. Have you heard of the men of Tyre?’

‘No.’

‘Pit men. They cut the winding ropes, smashed the engines and set fire to the coal.’

‘Why?’

‘To protest against their working conditions. It’s not natural to never see the sun. A pit is hell on earth. A mill is not much better. Folk call it progress. But there’s trouble brewing, mark my words.’

‘So what brings you here then? Why did you leave Liverpool?’

‘Oh, I travelled about. Done this and that. You know how it goes.’

We worked on all morning with Sticks chelping in my ear. At lunchtime the farmer brought bread and ale. I asked for water.

‘What’s wrong with ale, lad?’

I had no intention of turning into a Hindley.

‘Nothing, sir, I just prefer God’s water.’

‘Well, there’s a stream up yonder you can drink from. Or there’s the well in the yard.’

After we’d eaten we swapped around. Me and Sticks set to work on the wall. Behind us was a birch wood and down the valley the farm and the outbuildings. We could see the thatched roofs from where we grafted. I shifted the stones into different sizes, heaping them into sets, saving the large uneven stones for the coping. I enjoyed the work even though it was slow going, like piecing together a puzzle. Each stone had to be carefully selected so that it sat just right with its mates. We started with the largest, heaviest stones, for the foundation of the wall, working up so that it got slimmer as we built. Every now and again we would strengthen it with through stones that hitched the two sides. We chose the flat side of the stones to face the wall, filling in the gap between the two sides with the odd-shaped smaller stones left behind, then the large, boulder-like ones as coping to top the wall and make it solid. The sun was up and the larks were singing way above our heads. So high in the sky I couldn’t actually see them. I saw a puttock being attacked by two crows and later the same crows attacked a glead that was twice their size. It’s just one battle after another, I thought. Even in these placid skies.

‘Had a problem with rats last week. The barn was overrun with them. Had to get the rat-catcher in with his dogs. Took him the best part of the day to flush them out and even then he didn’t get them all,’ said Sticks as he looked to place the stone in his hand.

‘Well, where there’s hens there’s rats,’ I said.

‘You’re right there.’

‘And where there’s swine there’s rats.’

‘True enough. Where there’s folks there’s rats,’ he said and laughed. ‘Seems, sometimes, folks and rats are the same thing.’

We worked on in silence for a time, selecting the right stones, placing them, then finding a better stone for the job and starting again. For every three we laid we’d have to go back a stone. After we had built about half a yard, Sticks stopped working and took out his clay pipe. He sat on one of the stones and stuffed the bowl of the pipe with tobacco. He snapped off the end of the pipe and took out a striker and a brimstone match. He held the striker to the match until the sparks caught. Then he held the lighted match to the bowl. He puffed out smoke and smiled at his success.

‘What’s your vice then?’

‘Eh?’

‘Do you play cards at all?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘We usually have a game after supper. Ace of hearts, faro, basset, hazard. What’s your preference?’

On rainy days I’d played hazard with you plenty of times, Cathy. When the storms outside raged even too ferociously for our tastes. But the other games I’d never heard of.

‘I’ll probably sit this one out,’ I said.

‘No head for gambling, eh?’

‘Need to earn some money first.’

‘There’s a tavern up the road. There’s skittles and ring-thebull every night if that’s more your tipple.’

‘I’m not much of a player.’

‘There’s a cockfight at least once a week, sometimes a fistfight. If you’ve no taste for blood there’s always dancing.’

‘I’m not much of a dancer.’

‘Suit yourself. But if you work hard you’ve got to play hard. The one goes with the other,’ he said.

He finished his pipe and put it in his pocket. We worked on all through the afternoon. By the end of the day we’d built up two yards of wall. We cleaned our tools with rags and stored them safe for the evening, then we traipsed down the hill for supper. Sarah, the farmer’s wife, served up oatmeal, bacon and potatoes. She was such a wee thing that I couldn’t help but picture her union with Dan Taylor and wince at the prospect. Like an ox on top of a stoat. The farmer rolled out a barrel of beer. He untapped it and poured the beer into large flagons. He handed them around.

‘Not for me, thanks.’

‘That’s half your wages.’

‘I don’t drink beer more than I need to slake my thirst.’

‘Ah, spirits more your choice?’

‘I don’t drink spirits.’

‘I’ll have his portion,’ Jethro said, a short, stocky man with red hair.

‘Well, don’t think I’ll be paying you otherwise,’ the farmer said.

‘Leave him be,’ said his wife. ‘Can I get you anything else?’

‘Water if you’ve got it, please.’

‘There’s buttermilk?’

She fetched me an earthen pot of buttermilk.

The farmer seemed pleased with my work and said that he would take me on. For all my labour I was to be paid five shillings a week and a gallon of beer a day. I would drink what I needed to slake my thirst and sell the rest to the other labourers at thruppence a pint. If I could sell four pints a day, that would be another shilling, doubling my wage to ten shilling a week.

After I’d eaten I took a walk roundabouts. The farm consisted of a barn, a parlour, a dairy, peat-house, stables and mistal. There was also a chicken coop away from the buildings, with a fenced-in run where the birds could scrat. A dozen hens and a handsome cock. The window of the dairy had the word ‘Dairy’ carved into its lintel. I’d seen this before when we’d been out walking one time, Cathy. I remember you telling me that this was to ensure it would not be liable for the window tax. Another way the rich robbed from the poor.

I walked up the lane. A mile from the farmhouse, there was a short turn by a clump of sycamore. The lane was narrow and next to this a church. It was a small, steep-roofed, stone building, with a few arched windows in a stone tower, rising scarcely above the sycamore tops, with an iron staff and vane on one corner. There was a small graveyard, enclosed by a hedge, and in the corner of this, but with three doors opening in front upon the lane, was a long crooked old cottage. On one of the stone thresholds, a peevish-looking woman was lounging, and before her, lying on the ground in the middle of the land, were two girls playing with a kitten. They stopped as I came near and rolled out of the way, while I passed by them. One of the girls laughed, and the other whispered and pointed. The woman said something in a sharp voice. I wondered what she’d said and who she was. I felt that in some way I was being judged. Though they seemed far from a position of authority.

I wandered around the other side of the farm. Past the farmyard was another huge barn, a wagon-shed, the farmhouse, and the piggeries I’d ligged in the previous night. Close to was a mountain of manure that steamed and festered. The farmyard was divided by a wall, and milch cows were accommodated in the separate divisions. It was quite a place the farmer and his wife had. I wondered how he’d come by it. By hard graft or by cunning theft? Or by being born into it? Which is another kind of theft.

I made my way back to the outbuilding where the men were at their leisure.

Sticks asked me where I’d been. I told him about my perambulations and of the sharp-tongued woman.

‘That’s the wife of the farmer’s son,’ he said in hushed tones. ‘Be careful how you tread with the pair of them. She goes by the name of Mary and he goes by the name of Dick. I don’t know which is worse. I saw her crack a man’s skull open with a hemp-wheel last summer. He’s tapped different. He doesn’t lose it like she does. If he clobbered you over the head he wouldn’t raise his voice, or change his expression. There would be no sign of anger at all. Got to watch those ones, laa. The farmer’s no soft touch either. He’ll have you up at four o’clock in the morning and he’ll work you till dusk. You’ll earn every shilling, I’ll tell you that much. I’ve done all sorts in my time. At six years old I were a bird-scarer. I’ve been a gardener, land surveyor, bookkeeper for a brewery. Every type of manual labour. Doesn’t matter what you do, the master’s always got the upper hand.’

The farmer’s wife fetched more victuals. After bread and cheese and porter, the men brought out their pipes. One of them took a spill and lit it from the fire, lighting first his pipe, then passing it around. There was some conversation on the hardness of the times and the dearness of all the necessaries of life. There was talk of reform.

‘Why bother? It’ll only end up the same, either way,’ Jethro said.

Sticks butted in. ‘Listen, laa, why should the wealth be in the hands of so few? And why should they get to say how it goes, when we don’t get a say at all? Have we, as grafters, no right to get what’s fair? I’m talking about the courts of this land. They’re corrupt. Have you no opinion about that, soft lad?’

‘Opinions cost lives. That talk is high treason,’ Jethro said.

He pointed out that the penalty for which was to be hanged by the neck, cut down while still alive and disembowelled.

Jethro pulled a fork from the fire with a faggot on the end and blew on it to cool it. ‘And then, as if that’s not bad enough, his entrails burned before his face. Then beheaded and quartered.’ Just in case Sticks hadn’t got the message, he took the faggot and bit into it.

‘But apart from that, what’s the punishment?’ Sticks said.

There was much laughter at this.

‘Look, all I’m saying is that every man should have a vote. Whether lord or labourer, jack or judge,’ said Sticks. ‘Give every man his own acres so that he’s not beholden to any landlord. And give him a voice. Give him a say-so over his own matter, that’s all I’m saying.’

There was more grumbling and protestation.

‘I’m talking about universal suffrage, for heaven’s sake. God made us all equal.’

‘You won’t get that without a civil war, I’m telling you that.’ Jethro again, between bites of his faggot. ‘Mark my words, there’s them at the top and there’s men like us, and there’s no changing it.’

‘We’ve already had a war and where did that get us? Bloody nowhere, that’s where,’ said another man.

‘The only way you’re going up in this world is swinging from the gibbet,’ said yet another.

I let the sounds of their arguments drift over me. I had no interest in universal suffrage. Only in a particular form of suffering: yours and Hindley’s.

They talked some more, then the cards came out and I watched the men play.

‘Is that gypsy boy laikin’?’ Jethro said, pointing to my corner.

‘He’s no gypsy,’ Sticks said.

‘His skin is gypsy.’

Different games of cards were played and money changed hands. Jethro was well oiled by this point, and throwing his coins around. I watched him stroke his red hair distractedly as he chucked his money about. I saw him lose his hand, once, twice, then a third time, and in so doing, lose that week’s wage. I must learn to play this game, I thought. Jethro sat in his chair in the dark, smoking his pipe and supping ale. He was muttering under his breath, ‘What will she say? What will she say?’ Sticks, who was the winner, was smiling and laughing, dealing one more hand. Here was another man reaping where he had not sown and gathering where he had not strawed. There are more ways than one to skin a rabbit, Cathy. Ask a weasel.

‘I’ll tell you what,’ said Sticks to Jethro, ‘I’ll give you a chance to get even. How does that sound?’

Jethro pretended not to hear and sat in the dark sucking his pipe, which had now gone out.

‘Tomorrow even, bring that cock you were bragging about. I’ll bring one of mine, and we’ll have a little skirmish.’

Jethro grunted.

‘Suit yourself, then.’

But despite Jethro’s apathy, the next night after supper he disappeared for half an hour, returning with a cock in a willow cage. Inside was a black-and-red bird of some considerable size. A proud fowl with a penetrating gaze and a lustrous plumage. The men gathered around the cage to get a closer look. There was nodding of heads and a general air of admiration. Dan Taylor turned to Sticks.

‘Well then, get your battle stag, let’s see a bit of cocking.’

Sticks nodded. He stood up and shook the straw off his breeches. He walked off and returned with a cage containing a mottled brown-gold rooster, a similar size and weight to that of Jethro’s. It looked like the comb and wattle of both birds had been dubbed, so there was just a lip of red on the head of the birds, and a line of red under the neck. A party of men gathered around. I was introduced to Dick, Dan’s eldest son, and took an instant dislike to him. He had the same petty meanness in his eyes as Hindley. He was smaller than his father, with black hair and red skin. Where his father was broad and meaty, Dick was all bone with muscles like knots in string. The outline of his skull beneath his skin protruded. The men talked about which cock would win and bets were laid.

‘My money’s on Jethro.’

‘Mine’s on Sticks.’

‘Tha’s more a dunghill than a gamecock.’

Some men shuffled the bales of hay and straw so that an enclosed area was formed and the birds were released. The men jostled to get the closest. I watched the fight from some distance. The men were positioned at the furthest extremes of the makeshift arena. Before the fight the birds were slapped and their feathers ruffled to agitate them. At first the men held their birds by their back ends, lifting them up and down and towards each other. The spectators shouted encouraging words. The men approached each other so that the birds, still being held, could peck and squawk at each other to further agitate them. Then when the birds were fired up, the men let them go and they flew at each other. The feathers on the backs of the birds’ necks were stiff like a turned-up collar and what was left of their combs were gorged. Their tail feathers stood proud and they held their chests out. They faced each other, their necks protruding. The black one bobbed his head and the brown one followed. I imagined these cocks as me and Hindley. With me as the black one and Hindley the brown.

Then the brown one flew up, making a piercing squawk, striking out with his spurs. The black one retaliated by jumping over his opponent. They turned to face each other again. There was a stand-off before the birds squared up once more, strutting and sticking their chests out, clucking and squawking. A flapping of wings and the birds flew up. The black one was on the back of the brown, but then the brown bird flipped over and the table was turned. More strutting, then they squawked and pecked some. They started to spar more aggressively and it was hard to follow the action. There was screeching and blood. Feathers and dust. I couldn’t make out the details. The men cheered on.

I noticed Dick Taylor, standing apart from the men, not joining in or cheering, but smiling inwardly. His black eyes seemed blacker in his red face. Unlike the other men, his pleasure didn’t seem to come from the game itself. His joy was derived from the suffering of others. After a time, the commotion was over but I couldn’t tell who had won in the chaos and confusion. Both birds seemed to be bleeding badly. Neither was the victor. Dick was still smiling as money changed hands, the smile only a skull makes from the grave. I realised it was a different kind of battle I wanted with Hindley. Where the scars are worn on the inside. Whoever the loser and whoever the victor, their cuts would heal in time and they would be ready to fight again. But I didn’t just want Hindley dubbed, I wanted to watch his very spirit crushed.

With the exception of the red-skinned Dick, and the politically minded Sticks, the farm labourers were a simple enough bunch of men. As long as they had work during the day, ale and bread at night, card games and somewhere to lig down, they seemed agreeable. We all slept together in the barn, with a chaumin dish burning flaights. The arrangement being not that much more than I’d found in the hog barn, but I couldn’t really complain. It was dry and it was warm. We ate together in the kitchen in the morning. Cages hung from the ceiling beams with songbirds trapped inside. A blackbird, a nightingale and a throstle. An oak chest, a chest of drawers, a long table that accommodated us all around it, and chairs for us to sit on. The floor and tops were strewn with bowls and tins, jugs and mugs, syrup tins and porridge thibles. In the back kitchen the food was stored, beer brewed and oatcakes baked. The farmer’s wife was helped out by Mary, the peevish wife of Dick.

I decided I would stay here for a while. The work suited me and I enjoyed the company of this Sticks character. Or at least he didn’t lock me in with the beasts or take a whip to me. I kept my head down, sold my ale rations to the other men, and saved my pennies. I was biding my time until I had enough bunce to move on to Manchester town, maybe even Liverpool. I would save four pounds. That seemed a sum that would keep me from destitution and set me up wherever I found work next. I calculated that I could be back on the road again in eight weeks, if I kept clean.

We worked all week on the wall and by the Sunday it was finished. We stood back and admired our work. The wall was good and strong. No wind and no beast would break it. I looked around at the landscape all around me. Meadow, pasture and field enclosed by stone walls and beyond that moorland. Walls that reached up steep cloughs and bridged over fast-flowing becks. Walls that marked who owned what and marred the land they squatted upon.

It was the end of the first week and the farmer insisted that I accompany him to church. As you know, Cathy, I am no lover of the chapel, but it was easier to keep the peace. He loaded up a coach with the members of his family and me and Jethro and a few others followed on foot. Sticks refused to accompany us, saying that he could worship his God any place he liked. He didn’t need churches. When we got to the place of worship, we were expected to walk up the church and bow to the parson. The squire and other parish notables sat in state in the centre of the aisle and erected a curtain around their peers to hide them from the vulgar gaze of the likes of me and Jethro and the other men. The minister talked of virtue and charity. But I had neither virtue or charity, just bile and contempt. God was not my friend. I sought only the company of the devil. Indeed, I had much in common with him, for had he not been cast out of heaven and was he not now wandering the earth in search of his revenge?

Days went by, then another week. I had saved a full pound as I’d planned to do and was a quarter to my goal. There were more walls to build and we worked steadily every day, taking it in turns, using hammer, wedge and chisel to break stones in the morning, then hand and eye to build the wall in the afternoon. The next day, we’d swap it around. It helped to break up the monotony of the job. I mostly partnered with Sticks and we grafted with me listening and him talking. His conversation ranged from the political to the personal within the same breath.

‘Have you heard of the tithe awards, laa?’

‘What’s that?’

‘A tenth of produce given to the rector of the land. One pig in ten, one egg in ten, one cow in ten. But the mill dun’t have to give a tenth of their produce. What do you think about that then?’

I shrugged.

‘I tell yer, it’s unfair is what it is.’

‘I suppose it is.’

‘We’ve got to fight for a fairer system, laa. No one is going to make the world fairer, only us. By hard graft. You’ve got to fight for everything you get in this life. Even love. My first love was Mary. Fourteen years of age. I was seventeen. What a beauty. Like a painting. At the very first sight I was taken, I remember it like this morning. I had a feeling so strong for her that I forgot what I was supposed to be doing. I just wanted to be with her all day, morning, afternoon and evening. As soon as I’d finished my work I’d be there, like a dog. It was just like in the songs, when a temptress puts a spell on a man.’

Oh, I knew that feeling all right, Cathy.

The wall-building was slow but satisfying work. I liked holding the stones in my hands, turning them over. I liked their weight and hardness. Something that was solid and dependable. And it was good to stand back at the end of the day and look over what we’d achieved.

When the wall was done there was more work for me. Dan had stable work I could do and to which I was accustomed, and plough work to which I was not but soon became so. Every morning I rose before four of the clock and would go into the stable. There I would cleanse the stable, groom the horses, feed them, then prepare my tackle. I would breakfast between six of the clock and half past the clock. Then plough until three. I took half an hour for dinner, attended to the horses until I don’t know what hour, when I would return for supper. After supper, for extra bunce, I would either sit by the fire to mend the shoes of the farmer’s family or beat and knock hemp or flax, or grind malt on the quern, pick candle rushes, or whatever the farmer bade me do until eight of the clock. Then I would attend to the cattle. There was not much time for leisure, but the pennies were piling up and I kept a bag of them hidden in the woods in the hollowed-out trunk of an elm.

The other workers began and ended each day by thanking God, but I would do no such thing. And so this became my routine for the next few weeks. The work was hard but I grew strong and my thoughts turned again to my plan. I now had two pounds. I was halfway there. Perhaps in Manchester I could set myself up and be my own master. Every night I would wander to the hollow and count my pennies. Once I had counted them, I would pile them all carefully back into the bag and hide it in the hollow as a squirrel does an acorn. It was a disturbed night in the barn with the other labourers, as some of them snored or else talked in their sleep. When slumber did visit me I dreamed about you. Sometimes I would wake with you on top of me, but when I reached out to touch your skin you turned into air. In another dream, I came into your chamber and you were there in bed with Edgar and he was leering at me. Other times I’d dream I was with Hindley, with my hands around his throat, squeezing the life out of him, and I would wake with a jolt and the disappointment of an empty grasp.

I would lie on my back, trying to block out noxious smells and the noisy racket, filling my head with plans of revenge. Yes, I would make my fortune in Manchester or Liverpool, but at some point in the future, I intended to return to you, an improved gentleman. I remembered the adage of the hare and the tortoise. I would take my time. I would savour my vengeance. I would linger as it lied.

With this in mind, one day I got into conversation with Sticks and asked him what I could do to improve my situation.

‘You need to read and write, laa.’

‘I know my alphabet,’ I said.

‘That’s a start. But you look around you at those who can read and write and those that can’t. Every labourer here is illiterate, me excepted. Do you think the squire is illiterate? Do you think the parson is? Or the doctor or the lawyer or the judge?’

‘So why do you choose the life of a farm labourer if you can read and write?’

‘Like I’ve said to you before, laa. There’s them that’s running to something, and them that’s running away.’

‘Which one are you?’

‘No matter, laa, no matter. Look, you want to improve your station in life then you start with your letters and your words. Everything comes from that.’

Sticks was right: if I were to gain dominion over Hindley’s mind and over his estate, and also gain your true respect and be a worthy adversary to Edgar, I would have to go beyond the rudimentary lessons you taught.

‘So how would I go about it then?’ I said.

‘I tell you what, laa, there’s a Sunday school that’s been set up in the village by the Methodists there. Been going a few years now, and it’s not just for bairns.’

Sure enough, when I went into the village the following Sunday I was informed that there was indeed a school for youths of both sexes, from fourteen to twenty-one years of age, and that it was in a commodious room at number four Sheppard Street. I attended one of the sessions. There were about twenty pupils sitting on the floor as there were no chairs. Most of them looked to be farm labourers. The teacher was a Methodist called George, simply dressed in black with a white silk scarf. His skin was pale and his hair was short and parted on one side. He copied out some passage from the bible in neat handwriting, using chalk and a slate, and said it was our duty to learn to read it for ourselves. He turned to us and picked up a bible. He held it aloft.

‘God gave you eyes and a brain. This book is not just for priests and nobility, it is for you and your kin, and it’s your duty to read the truth within.’

He called us ‘children of wrath’. He chalked up the letters of the alphabet on the board and we had to join in as he sang them out. It was a joyless and repetitive experience. I tallied that the classroom was not for me. I tried to take instruction but something in my head resisted. I was familiar with the alphabet in any case and would as much be able to self-learn given a book or two and some time. I went on three or four separate occasions and was by then further on with my learning but not sufficient as I’d hoped. When George was taken up with tutoring one morning, I took hold of one of the bibles in the room and secreted it inside my surtout. I knew its stories well from Joseph’s sermons, and figured this would help me to sightread. I waited for the lesson to come to an end, then walked out of the school bidding George good day and saying that I would see him the following Sunday, even though I had no intention of going to the school ever again.

So, the next Sunday, after telling the farmer and his wife that I was off to school, I walked up and onto the moor and, after some searching, I found a shallow cave where I could self-school. It was a good spot, a long way from any path, and well hidden. I spent every spare hour I had there. When the workers were playing cards and drinking ale, I would sit with my book. I brought blankets and made the space comfortable. I found a flint and steel in one of the barns, collected kindling and wood, filched a few flaights from the lower barn, and there I’d stay, with a fire to keep me warm, nicely sheltered. Once or twice I even spent the night there, waking at dawn and sneaking back into the barn while the others were still sleeping, joining the rest of the labourers without anyone the wiser. But mostly I studied. It was hard-going to begin with. I opened the book on the first page and commenced my learning. The first word was easy. I knew the sound of ‘I’ and ‘n’ and could put them together. ‘The’ I also knew. The third word was my first challenge, but by saying it aloud in stages, I got there. First ‘beg’ then ‘inn’ then ‘ing’: ‘beginning’. Many hours those first few pages took me and I was glad I had no company to hear my clumsy efforts. A Hindley or a Joseph would soon have made me regret my efforts, sure enough.

It was all God said this and God said that. And God made this and God made that. I always liked the story of the Garden of Eden. And I was pleased when I got that far. The story was familiar to me but it was good to reacquaint myself with its lesson. Though it was not the orthodox one. God lied to Adam and Eve. He said that if they ate the forbidden fruit then they would die. But the fruit was not poisonous and they did not die. In any case, God had made the tree and made the fruit. Then the serpent came along and talked to Eve. But the serpent did not lie because he said that if they ate the fruit they would know good and evil and the snake was right. They did learn good and evil when they ate the fruit. God lied. The devil told the truth. When they were cast out of Eden, I thought that this was for the best. Who would want to stay in Eden under the authority of a tyrant? I was on the side of the snake. For wasn’t the snake also a child of heaven?

I recalled that day when we clambered down Duke Top, through the wooded clough past Cold Knoll, resting in the heather near Lower Slack.

‘What’s that?’ you whispered.

I didn’t see it at first, so well hidden was it in the undergrowth, but as my eyes adjusted, I saw it, a viper’s nest, the mother with her babies underneath her belly. They were all curled around each other for warmth. The mother bobbed her head and flicked her tongue. She saw us watching her and coiled protectively around her brood. We sat and watched, as stiff as rocks, not wanting to disturb the scene. We hardly even dared to breathe. At last we crept away, leaving them alone again. There was something majestic about that creature and we had both been bewitched by her finery.