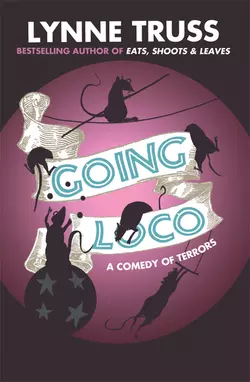

Going Loco

Lynne Truss

A wonderful comic novel from the bestselling author of ‘Eats Shoots & Leaves’.Belinda Johansson is a woman frantic, overwhelmed by the demands of work and home. Having it all? Pah. Belinda doesn't want any of it. Deep in research for her magnum opus - a definitive account of the doppelgänger in classic gothic fiction - she fails to notice the echoes of these ghoulish tales disturbingly close at hand. For not only is the cleaning lady taking over her life, but the identity of her husband, Stefan, is also in question. Is he a harmless geneticist from Sweden, or actually a cunning clone? Why is the cleaning lady's previous employer having a breakdown, and what on earth has the rat circus got to do with any of this?

LYNNE TRUSS

Going Loco

A Comedy of Terrors

To Mum, who never had the choice

Contents

Cover (#u312a964f-e44f-5bca-b736-a8e5b43331aa)

Title Page (#u8cbd3cd9-14fe-5cff-b7e5-742c53324b0e)

Part One (#u133c93dc-f973-5ee8-adec-5b1540ad2677)

One (#u47a17f47-1817-5458-be45-44372b59e193)

Two (#ue08885d9-01a8-59b6-ab2f-ac829de731a8)

Three (#u6ea96b54-93b8-5289-9131-131e021570ee)

Four (#u01d35ea6-117e-5aff-8c54-fe7e8daa38f4)

Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same author: (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part One (#ulink_638c212b-4c2e-5d5b-a849-aaab7e6e44b2)

One (#ulink_d353c213-26d4-5c21-83d7-cd289517d6af)

Since being the heroine of her own life was never quite to be Belinda’s fate, we may as well begin with Neville. Belinda was a real person, while Neville was an imaginary rat with acrobatic skills; but since he inhabited the pit of her stomach, their destinies were inextricable. Since Christmas, at least, they had started each day together, and if either performed an action independently – well, neither knew nor cared. Belinda would wake, and at the first choke of anxiety concerning the day to come, Neville commenced preliminary tumbling. Belinda clutched her throat; Neville donned a body stocking and tested his trampoline. It was pretty alarming sometimes, a bit too vivid, especially for someone who had never been particularly drawn to the romance of the Big Top. But she had no control over it. By the time Belinda was dressed and committed to the beat-the-clock panic that seemed to have become her waking life, Neville was juggling flaming brands on a unicycle and calling authentic acrobat noises such as ‘Hup!’ and ‘Hip!’ and ‘Hi-yup!’

Belinda did once mention Neville to Stefan, but since her husband’s own alimentary canal had never been domicile to a rat in spangles, he didn’t know how to react. Being a clever Swedish person, he was eager to learn new idioms, new English phrases, which was why Belinda sometimes gambled that he might understand something emotionally foreign to him as well. But when Belinda complained, ‘And now I’ve got a rat in my stomach,’ he had merely looked up from his book, sighed a bit, and turned down the volume on Abba: Gold.

‘A rat?’ he queried. ‘This is a turned-up book.’

‘Mm,’ she agreed.

They listened to Abba for a bit. Stefan mouthed the words. Perhaps under the influence of the song, Belinda found herself staring at the ceiling, wishing she were somewhere else instead.

His scientific mind slid into gear. ‘What sort of rat? Rattus norwegicus?’

‘I don’t think so,’ she said. No, the name Neville had no ring of Scandinavia. ‘He’s more of an acrobatic rat. In tights. With a high wire and parasol.’

Stefan gave her one of his steady, serious smiles; she broke the gaze, as always, by pulling a silly face, because its intensity scared her.

‘You’re working too hard,’ he said, quietly. ‘Jack is a dull boy, I think.’

‘I know, I know. Of course I am. That’s what I’m trying to tell you.’

‘So why do you invent a rat? Why not say, “Stefan, my old Dutch, help. I’m working my trousers to the bone, but I just can’t beat the clock”?’

Belinda pouted. ‘I don’t think I did invent him. I can feel him doing back-flips.’

Abba started singing ‘The Name of the Game’. Stefan turned up the volume again.

At which point Neville walked on his front paws through her intestinal tract, gripping a beach-ball between his back feet.

‘Ta-da!’ he cried.

A couple of things need to be made clear about Belinda Johansson. First, she was not Swedish (obviously). Second, she was under the rather hilarious illusion that she had a hard life, when in fact she had an enviable existence as a freelance literary critic and creative writer in some demand, living in one of the better bits of South London. And third, if she saw an abandoned sock on the bathroom floor, she would glare at it defensively rather than pick it up and sling it into a laundry bag.

This last tendency may not sound too bad, but as any slattern can attest, neglected balled-up socks have a talent for embodying reproach. ‘I’m still here,’ the sock will tell you, in an irritating sing-song tone, on your next five visits to the bathroom. ‘I’m going crusty now. And I believe I missed the wash on Sunday morning.’ Belinda’s healthy intelligence would not allow her to be browbeaten by mouldy hosiery, which was why she wouldn’t stoop to silencing its reproaches by simply tidying it up. But add this insinuating sock to the pile of attention-seeking newspapers in the kitchen (‘We’re still here too, lady!’), the ancient wine corks accumulating fluff and grease (‘Remember us?’), and the deadline for her latest potboiler (‘Tuesday, or else’), plus the pressure on her long-term book on literary doubles (‘You bitch! I can’t do it on my own!’) and you begin to understand why Belinda was giving house room to the rat. The deadlines alone she might have managed. It was the cacophony of reproach from all fucking directions in this fucking, fucking house that she couldn’t tolerate much longer. It’s sad but true that, had Belinda’s DNA not tragically lacked the genetic code for basic household organization, none of the following story need have taken place.

You couldn’t feel sorry for her, and nobody did. Many women had more responsibilities than Belinda, with considerably fewer advantages. At the nice age of thirty-six, she lived in a nice, large Victorian villa in Armadale Road, Battersea, with a nice, rather entertaining Swedish husband she’d met well into her thirties. Her work was nice, too – compiling a serious literary book alongside more lucrative horsy stuff for girls. On this Monday morning in February she was about to deliver A Rosette for Verity and collect three thousand pounds. The Swede was a senior scientist, so the Johanssons had money. Only Stefan’s habit of perusing Over-reach Your English for Foreigners on the toilet each morning could be seen as a cause of strain.

Unfortunately, however, the justice of Belinda’s complaints was not the point. The point was, her body was a twenty-four-hour adrenaline pumping station. And at the time this story starts, Belinda’s behaviour was deteriorating badly. She had caught herself waving two fingers at the postman from behind the curtains, just because he innocently delivered more post. ‘Take it away,’ she yelled. ‘Don’t bring it, take it away!’ A magazine editor had rung up with the offer of a laughably easy horse-tackle column (she’d coveted it for years), and instead of saying, ‘That’s great!’, she’d barked, ‘Do you think I just sit here with my thumb up my bum waiting for you to ring? Get a life, for God’s sake.’ At the supermarket, she had rammed her trolley into that of a dithering pensioner, saying, ‘Look, have you got a job?’ In short, the flight-or-fight mechanism Nature gave Belinda for emergencies had gone horribly haywire, as if someone had removed the knob, and lost it.

Stefan would tell her to take off the weight, or hang loose. Stefan was one of those people who has a regular job – or even, in recidivist lapses, a ‘yob’ – who attends college in office hours, and comes home in the evening to relax. In about fifteen years, he would retire. True, a certain amount of research was required of him, but it was no skin off his nose, as he was proud of remarking. Why Belinda made such a meal of things, he didn’t know.

So things came to a head in that pleasant suicide month of February, on a Monday morning. Belinda was racing out of her agreeable house at nine thirty-five for a ten a.m. train from Clapham Junction, and there was (for once) the faintest chance she would make it. She felt terrible, afflicted by a painful and humiliating dream in which she had punched Madonna on the nose for hijacking her car, only to discover that the passengers were all disabled children. This was not the sort of dream to be dislodged easily. The children had waved accusing crutches at her through the car windows, and though she’d grovelled to Madonna, she’d woken unforgiven and felt like a murderer.

Meanwhile, the manuscript of A Rosette for Verity had done its usual job of transmogrifying into a bowling ball in her shoulder-bag. She was brushing her hair with one hand and fumbling for bus-fare with the other, and Neville was helpfully practising trapeze. ‘Steady on, Neville,’ she muttered absently. And then the telephone rang in the hall.

‘Oh bugger,’ she said, as the phone trilled. Oh no. She flailed about, as if caught in quicksand. Here she was, late already, hair not dry, feeling sick with guilt about the poor crippled kiddies, and wearing a strange fashionable black slidy nylon coat she’d allowed her mother to buy her, which made her feel like an impostor.

‘Ring-ring,’ it said, as she passed.

‘Nope,’ she told it.

‘Ring-ring,’ it persisted. ‘Remember me?’

So she snatched up the receiver and answered the phone. Why? Because life’s like that. It’s a rule. The later you are, the less time you can give to it, the more vulnerable you are to far-fetched misgivings. What if it’s the publisher phoning to cancel? Or Stefan with his head caught in some railings?

All her life, Belinda’s idea of an emergency was someone with their head caught in some railings.

‘Hello?’

A high-pitched male voice with an Ulster accent. A friendly voice, but nobody she knew.

‘May I speak with Mrs Johnson, please?’

‘Johansson,’ she corrected him automatically, shooting a despairing glance at the hall clock. Why did cold-callers always waste time assuming you aren’t the person they’ve phoned? She gritted her teeth. Before catching the train she needed to buy some stamps, renew her road tax, phone a radio producer and touch up chapter three, because she’d just remembered the bay gelding of Verity’s chief rival Camilla had emerged from a three-day event as a chestnut mare. Perhaps he had got something caught in some railings. Dramatically (and distractingly) Neville swung back and forth in a spotlight, with no safety-net, accompanied by a drum-roll. Meanwhile her bag slid off her shoulder with a great whump, as if to say, ‘Well, if we’re not going out, I’ll stop here.’

‘Hello Mrs Johnson, my name is Graham, and I work for British Telecom. We recently sent you some details of new services. I wonder, is this a good time to talk?’

‘Hah!’

Belinda gave a hollow laugh and started to fill this annoying wasted time by hoisting her bag from under the hall table – the area Stefan cheerfully called the Land That Time Forgot About. Heaps of stuff made a big tangly nest under here, even though Belinda had frequently begged Mrs Holdsworth just to chuck it all out. She looked at it now, and it said, ‘Ooh, hello, remember us?’ rather excitedly, because it didn’t get the chance as often as the socks in the bathroom or the newspapers in the kitchen. Weekly free news-sheets and fluff in lumps mingled with Stefan’s favourite moose-hat, and some spare coat buttons. Three empty Jiffy-bags bled grey lunar dust over a novelty egg-timer, a bottle of Finnish vodka, a CD of the 1970s Malmö pop sensation the Hoola Bandoola Band, and an ice-hockey puck. And there among it was a single white envelope bearing the symbol of registered post. ‘Sod it,’ she said, as she stretched to reach it.

‘This is Graham from BT,’ the man reminded her. ‘Is this a good time to talk?’

She looked at the clock again: ten forty-three. This envelope clearly contained the cash-card she’d argued about with the bank. ‘You never sent it!’ she’d said. ‘But you signed for it!’ they replied. And here it was, saying, ‘Remember me?’ In her stomach, Neville started calling other rats for an acrobatic display – ‘Yip!’ ‘Hoopla!’ ‘Hi-yip!’ From the way their weight was shifting around, they had started to form the rodent equivalent of the human pyramid. She felt compelled to admire their ingenuity. It felt as though they’d acquired a springboard.

‘Look, I’ve got to go. This isn’t convenient.’

Graham made a sympathetic noise, but did not say goodbye. Instead, he asked, ‘Perhaps you could suggest a more convenient time in the next few days?’ It was a routine phone-sales question, but it unleashed something. Because suddenly Belinda lost control.

It was because he had asked her to think ahead, perhaps. That’s what did it. Normally she went through life as if driving in the country in the dark, just peering to the end of the headlights and keeping her nerve. But daylight revealed the total landscape. ‘A more convenient time in the next few days’? Her lip quivered. She considered the next few days, a vision of the M25 choked with cones and honking, with nee-naws – of appointments and deadlines and VAT return and, and – and started to sniff uncontrollably.

Damn this bloody rushing about. Sniff. Damn this fucking life. Sniff, sniff. She’d had a big argument about this letter, and why had it been unnoticed on the floor? Why? Because there was no time to Hoover this fluff or to clear these papers. Because there was no time to sack Mrs Holdsworth for her incompetence. No time to sew buttons on, or build a nice display cabinet for moose-hats, listen with full attention to Hoola Bandoola with a Swedish dictionary, or get to the bottom of the ice-hockey puck once and for all.

There was never any time, and it wasn’t fair. She glanced into the kitchen, where the table was heaped with unpaid bills, diaries. On each of the stairs behind her was a little pile of misplaced items tumbled together (foreign money with holes in, nail scissors, receipts). If items had human rights, the UNHCR would be down on Belinda like a ton of bricks. On the wall above the phone was a handsome blue-tinted postcard of the Sussex Downs with a serene quotation from Virginia Woolf: ‘I have three entire days alone – three pure and rounded pearls.’ Stefan had given it to her ‘as a yoke’. She saw it now, and in an access of Bloomsbury envy familiar to every other working female writer of the twentieth century, Belinda simply broke down and sobbed.

‘Mrs Johnson?’

Belinda made a wah-wah sound so loud it shocked her. She wiped her nose with the back of her hand, and then, at a loss, wiped the back of her hand on mother’s glossy coat – which was of a material, alas, designed specifically not to absorb mucal waste.

No one would understand what a bad moment this was. Belinda was not the sort of person who bursts into tears. In times of stress, she simply increased adrenaline production while Neville ran a three-ring circus. She didn’t cry. Stefan hated cry-babies. His imitation of his first wife’s cry-baby mode (‘Wah, wah! I’m so unhappy, Stefan!’) was quite enough to put anybody off.

‘Perhaps you would like some time?’ Graham persisted. ‘I can tell you don’t have time right now.’

‘No, I don’t have any time,’ whimpered Belinda.

‘Shall I give you a couple of days?’

Silence. A sniffle.

‘Mrs Johnson, would you like a couple of days?’

At which point, Belinda sank to the floor again, to sit flat on her bum and sob. ‘Would I like [sniff] a couple of—?’ A loud, helpless wah-wah was coming down the phone.

‘Have you got a tissue, Mrs Johnson?’ Graham asked, gently.

‘Jo-hansson!’ she sobbed.

‘I’ll give you a couple of days.’

Belinda struggled to her feet, dragging her bowling ball towards her.

‘Give me three pure and rounded pearls, Graham. What I want’ – she sniffed noisily – ‘is three pure and rounded pearls.’

You shouldn’t dislike Belinda. She had a great many redeeming features. She knew lots of jokes about animals going into bars, for example. But clearly she had a big problem negotiating the routine pitfalls of everyday existence.

‘It’s a control thing,’ her friend Maggie said (Maggie, an actress, had done therapy for thirteen years). ‘You want total control. You somehow think an empty life is the ideal life, and a full life means it’s been stolen by other people. You think deep down that everything in the universe – including your friends, actually – exists with the sole malevolent purpose of stealing your time.’

‘Oh, I see,’ said Belinda. ‘And is this the five-minute insult or the full half-hour?’ But secretly she was aghast. The description was spot-on. Mags was right: even this short conversation now required to be added to the day’s total of sadly unavoided interruptions.

The first thing she’d noticed about Stefan was that he smiled a lot, especially for a Scandinavian. He was solemn, and said rather peculiar things, like ‘A nod is as good as a wink’ and ‘That’s all my eye and Betty Martin’, when first introduced, but he smiled even at jokes about animals in bars, which was encouraging. They had met three years ago in Putney at her friend Viv’s, at a Sunday lunch, where they had been seated adjacently by their hostess, with an obvious match-making intent. Belinda resented this at first, and almost changed places. Viv had an intolerable weakness for match-making. In a world ruled by Vivs, happy single people would be rounded up and shot.

But she took to Stefan. He was recently divorced, and recently arrived in London to teach genetics at Imperial College. He was solvent, which counted for a lot more than it ought to. Tall, blond, slender and a bit vain, he wore surprisingly fashionable spectacles for a man of his age (forty-eight at the time). Of course, he wasn’t perfect. For a start, middle-of-the-road music was a passion of his life, and he would not hear a word spoken against Abba. He idolized Monty Python, played golf as if it were a respectable thing to talk about, and was proud of driving a fast car. A couple of times he told stories about his mentally ill first wife, which struck Belinda as cruel. Also, he was condescending when he explained his work on pseudogenes. Like most specialists, she decided, he muddled reasonable ignorance with stupidity.

But basically, Belinda fancied him straight away, and had an unprecedented urge to get him outside and push him against a wall. In the one truly Lawrentian moment of her life, she felt her bowel leap, her thighs sing and her bra-straps strain to snapping. Having been single for seven years at this point, she knew all too well that she must act quickly – a specimen of unattached manhood as exotic and presentable as Stefan Johansson would have an availability period in 1990s SW15 of just under two and a half weeks. Her biological clock, long reduced to a muffled tick, started making urgent ‘Parp! Parp!’ noises, so loud and insistent that she had to resist the impulse to evacuate the building.

The lunch was half bliss, half agony, with Stefan dividing his attention between Maggie and Belinda, and finding out whose biological clock could ‘Parp’ the loudest. Perhaps his understanding of natural selection contributed to this ploy. Either way, Belinda – who had never competed for a man – was so overwhelmed by the physical attraction that she contrived to get drunk, make eyes at him, and (the clincher) ruthlessly outdo Maggie at remembering every single word of ‘Thank You for the Music’ and the Pet Shop Sketch.

‘Lift home, Miss Patch?’ he’d asked her breezily, when this long repast finally ended at four thirty. She’d known him only four hours, and already he’d given her a nickname – something no one had done before. True, he called her ‘Patch’ for the unromantic reason of her nicotine plasters; and true, it made her sound like a collie. But she loved it. ‘Miss Patch’ made her feel young and adorable, like Audrey Hepburn; it made her feel (even more unaccountably) like she’d never heard of sexual politics. ‘Lift home, Miss Patch?’ was, to Belinda, the most exciting question in the language. Soon after it, she’d had her tongue down his throat, and his hands up her jumper, with her nipples strenuously erect precisely in the manner of chapel hat-pegs – as Stefan had whispered in her ear so astonishingly at the time.

And now here they were, married, and Belinda was having this silly problem with the El Ratto indoor circus; and Maggie could decipher plainly all the selfish secrets of her soul, and she’d burst into tears like a madwoman talking to a complete stranger on the phone because he offered her big fat pearls but didn’t mean it. However, Stefan was still smiling because (as she had soon discovered) he always smiled, whatever his mood. He had told her that he was known in academic circles as the Genial Geneticist from Gothenburg.

‘So what did your masters think of Verity’s Rosette?’ he asked. It was Monday evening, and they were loading the dishwasher to the accompaniment of ‘Voulez Vous’.

‘A Rosette for Verity? They’ll let me know. We discussed the idea that she might break her neck in the next book and be all brave about it, but I said, “No, let’s do that to Camilla.” Six Months in Traction for Camilla – what do you think?’

He smiled uncertainly. ‘You are yoking?’

‘A bit, yes.’

‘You remember we visit Viv and Yago tomorrow?’

‘We do?’ she said. ‘Damn. I mean, great.’

‘Maggie will be there, too. Maggie is a good egg, for sure. I want to tell her she was de luxe in the play by Harold Pinter. Mind you, no one could ever accuse Pinter of gilding the lily, I think.’

‘Shall we watch telly tonight? The Invasion of the Body Snatchers is on.’

Although she was really desperate to get on with some work, she felt guilty about Stefan, and regularly made pretences of this sort. Hey, let’s just curl up on the sofa and watch TV like normal people! She fooled nobody, but felt better for the attempt. The trouble was, whenever she felt under pressure, she had the awful sensation that Stefan was turning into a species of accusatory sock. Besides which, it was nice watching television with him, and cuddling. She always enjoyed those interludes with Stefan when they didn’t feel the need to speak.

‘Don’t you want to work?’

‘Well, I—’

He smiled.

‘You have been Patsy Sullivan today, all day?’ (Patsy Sullivan was her horsy pseudonym.) ‘Then you must work yourself tonight.’

‘Are you sure? It’s just, you know, it’s February, and the book is due in October. And I feel this terrible pressure of time, Stefan. And I’ve got fifty-three Verity fan letters in big handwriting to answer. I have to pretend to the poor saps that I live on a farm with dogs and stuff. And I’ve got to go and see saddles tomorrow in Barnet. Do you know the line of Keats – “When I have fears that I may cease to be, before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain”?’

Stefan thought about it. ‘No, I don’t know that. But it sounds like you.’ He turned to go, then stopped. ‘So I shall look forward to tomorrow night. Now just tell me about Yago and Viv. Why is it that whenever I perorate in their company, they react as though I have dropped a fart?’

This was difficult to answer, but she managed it.

‘They’re scared of you, Stefan. It’s scary, genetics. There you sit, knowing all about the Great Code of Life, and all Viv and Jago know about is Street of Shame gossip and the Superwoman Cook Book. It’s a powerful thing, knowing science in such company.’

‘In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king?’

‘Exactly.’

‘I have got bigger fish to fry?’

‘That’s it.’

Belinda was glad she’d reassured him. She decided not to mention the fart. ‘Even I’m scared of you, a bit,’ she said, squeezing his arm and looking into his lovely eyes. They were like chips of ice, she thought.

‘Oh, Belinda—’ he objected.

‘No, it’s true. I sometimes think you could unravel my DNA just by looking at me. And then, of course, you could knit me up again, as someone else with different sleeves and a V neck.’

Belinda envied the way Stefan’s work fitted so neatly into the time he spent at college. She imagined him now with enormous knitting needles, muttering, ‘Knit one, purl one, knit one, purl one,’ in a loud, clacky room full of brainy blokes in lab coats all doing the same, trying to finish a complicated bit (turning a heel, perhaps) before the bell rang at five thirty.

People were always telling Belinda that genetics was a sexy science, but Stefan said it was harmless drudgery – and she was happy to believe him. Clueless about the nitty-gritty, she just knew that his research involved things called dominant and recessive genes. ‘So some genes are pushy and others are pushovers, and the combination always causes trouble?’ she’d once summed it up. And he’d coughed and said gnomically, ‘Up to a point, Lord Copper.’

At that momentous Sunday lunch, she had not told him much about her own work. As she discovered later, Swedes don’t ask personal questions; they consider it ill-mannered. But she had told him about Patsy Sullivan, and made him laugh describing the horsy adventures. However, the time she regarded as daily stolen from her had nothing to do with her desire to write about red rosettes for handy-pony. It wasn’t time she wanted for ‘herself’, either. Magazines sometimes referred to women making time for ‘themselves’, but driven by her Keatsian gleaning imperative, Belinda had absolutely no idea what it meant. ‘Make time for yourself.’ Weird. Chintzy wallpaper probably had something to do with it. Long hot baths. Or chocolates in a heart-shaped box.

Thus, if well-intentioned people chose to flatter Belinda in a feminine way, it just confused her. ‘Buy yourself a lipstick,’ Viv’s mother had said during her university finals, giving her a five-pound note. But the commission had made her miserable. She’d hated hanging around cosmetics counters with this albatross of a fiver when she could have been revising the Gothic novel in the library. Belinda’s revision timetable had been incredibly impressive, and very, very tight. Only when Viv absolved her with ‘Buy some pens, for God’s sake,’ did she race off happily and spend it.

Yes, for someone who lived so much in her head, it was an alien world, that feminine malarkey. Luckily the other-worldly Stefan didn’t mind too much, but Belinda’s well-coiffed mother despaired of her, and left copies of books with titles like Femininity for Dummies lying around in her daughter’s house. Yet even as a teenager Belinda had flipped through all women’s magazines in lofty, anthropological astonishment, amazed at the ways contrived by modern women to occupy their time non-productively. Facials, for heaven’s sake. Leg-waxing. Fashionable hats. Stencils.

From this you might deduce that Belinda’s secret personal work was of global importance. But she was just writing a book called The Dualists, a grand overview of literary doubles through the ages. Being Patsy half the time had given her the idea. ‘Like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde,’ she explained, when people looked blank. ‘Or like me and Patsy Sullivan.’ But if she implied that she took the subject lightly, she certainly didn’t.

In fact, like most areas of study, the closer you got to the literary double, the more importantly it loomed; the more it demonstrated links with life, the universe, everything, even genetics and photocopying. Abba impersonators, Siamese twins, Face/Off – the world was full of replicas. And why was the genre so popular? Because everyone believes they’ve got an alternative, parallel life – in Belinda’s case, perhaps, the ideal existence of that unregenerate toff Virginia Woolf, with her pure and rounded pearls. This parallel life was just waiting for you to join it, to stop fannying about. Every time you made a choice in life, another parallel existence was created to demonstrate how your own life could have been. Surely everybody felt that? Surely everybody looked in the mirror and thought, That’s not the real me. It used to be, but it’s not now. Surely everyone measured themselves against their friends? Especially these days, when everyone was so busy?

Either way, for the past three years, between all the demands of Patsy and socks (and Stefan), Belinda had left unturned not a single existential book in which a malevolent lookalike turned up to say, ‘I’m the real you. And hey, you’re not going to like what I’ve been doing!’ Her office, formerly the dining room, was heaped with books and notes. She had become an expert on the dark world of Gogol and Dostoevsky, Nabokov, Stevenson and Hogg. Name any writer who shrieked on passing a reflective shop window, and Belinda was guaranteed to have a convincing theory about the personal crisis that conjured up his story, and summoned his double to life.

Oh yes, the nearer you stood to the literary double, the more (spookily) it told you universal truths of existence. Unfortunately for Belinda, she could never quite appreciate that the further you stood back from the literary double (as all her friends effortlessly did), the more it resembled leg-waxing by other means.

The phone rang at ten o’clock and Stefan answered it.

‘It was a man from British Telecom, seemed a bit rum,’ he reported to Belinda, who was curled up with a book in her study, Neville snoozing contentedly save for the occasional twitch of his little pink tail. ‘His name was Graham.’

Belinda bit her lip. ‘Oh yes?’

‘He was ringing from home, to check you were recovered. I told him, “This is ten o’clock at night, were you born in a barn?”’

Belinda looked amazed. Neville stirred.

‘You are all right, aren’t you, Miss Patch? He said he only mentioned his money-off Friends and Family scheme and you wept, like cats and dogs.’

She nodded. She felt cornered. When women had breakdowns, their husbands left them. It was a well-known fact. When Stefan’s former wife Ingrid had a breakdown, he left her good and proper, in an institution in Malmö.

‘You try to do too much,’ he said.

‘I know.’

‘It’s not my fault, is it?’

Belinda gasped. His fault?

He searched her face, which crumpled under the strain of his kindness.

‘Of course it’s not,’ she snuffled.

‘Come to bed,’ he said, reaching to touch her.

‘All right,’ she said.

‘You must not forget, Belinda. No man is an island.’

‘No.’

She put down her book, and got up.

He smiled. ‘The thing about you, Belinda, is you need two lives.’

‘Well, three or four would be nice,’ she agreed, switching off the light. ‘Why don’t you make some clones for me? You know perfectly well you could knock up a couple at work.’

Two (#ulink_37291374-4b38-587c-823a-f564379bbd0e)

It was eleven thirty on Tuesday night in Putney, the candles were guttering, and Jago was telling a joke over coffee. It was one of the smart showbiz ones he’d picked up on a trip home to New York several years ago.

‘So the neighbour in Santa Monica says, “I tell ya, it was terrible. Your agent was here and he raped your wife and slaughtered your children and then he just upped and burned your damn house down.” And the writer says, “Hold on a minute!…”’ Here Jago paused for a well-practised effect. His guests looked up.

‘“Did you say my agent came to my house?”’ Belinda laughed with all the others, although she’d heard Jago tell this joke before. Oh, understanding jokes about agents, didn’t it make you feel grown-up and important? She remembered the first time she’d managed to mention her agent as a mere matter of fact, without prefacing it with ‘Oh listen to me!’ It had been one of those Rubicon moments. No going back now, Mother. No going back now.

To be honest, Belinda’s grand-sounding agent – A. P. Jorkin of Jorkin Spenlow – was a dusty man she’d met only once. But he was adequate to her meagre purposes, being well connected as well as reassuringly bookish, though alas, a sexist. ‘Let’s keep this relationship professional, shall we?’ she’d said to him brightly in the taxi, when he put his hand on her leg and squeezed it. ‘All right,’ he agreed, with a chalky wheeze, pressing harder. ‘How much do you charge?’

Ah yes, she’d certainly made a disastrous choice with Jorkin, but changing your agent sounded like one of those endlessly difficult, escalatory things, like treating a house for dry rot. For a woman who can’t be arsed to pick up a sock, it was a project she would, self-evidently, never undertake. ‘Perhaps he’ll die soon,’ she thought, hopefully. Random facial hair sprouted from Jorkin’s cheek and nose, she remembered dimly. She really hated that.

Jago’s agent, of course, was quite another matter. Not that Jago ever wrote books, but having a big-time agent was an essential fashion accoutrement once you reached a certain level in Fleet Street: the modern-day equivalent of a food-taster or a leopard on a chain. Dermot, who often appeared on television, was famously associated with those other busy scribblers, the Prime Minister and the Archbishop of Canterbury. Complete with his too-tight-fitting ski tan, he was tonight’s guest of honour, amiably telling Stefan about rugby union in South Africa, fiddling with a silver bracelet, and recounting jaw-dropping stories about being backstage at Clive Anderson. No random facial hair on this one. No hair at all, actually. When she’d told him in confidence about her book on literary doubles, he’d laughed out loud at the sheer, profitless folly of it. ‘Here,’ he’d said, taking off his belt with a flourish. ‘Hang yourself with that, it’s quicker.’

Tonight he was feeling more generous, so he gave her a tip. ‘Belinda, why don’t you write a bittersweet novel about being single in the city with a cat?’

‘Perhaps because I hate cats and I’m not single, and I don’t write grown-up fiction.’

‘OK, but single people sell.’

‘Which is why I’m writing about double people, no doubt.’

‘Well,’ he sighed, leaning towards her and picking imaginary fluff from her shoulder, ‘you said it.’

Belinda wondered now whether she should have taken his advice. Was her literary work above fashion? Or just so far beyond it that it had dropped off the edge? She poured herself some more wine and took a small handful of chocolates. Relaxation on this scale was a rare and marvellous thing. Neville had given the other rats the night off, evidently, and was spending the evening quietly oiling his whip. Stefan was now teasing Dermot about the real-life chances of an attack of killer tomatoes (for some reason, Dermot was rather exercised on this point); Jago was arguing good-naturedly with Dermot’s assistant about modern operatic stage design. Maggie (bless her) seemed to be adequately hitting it off with the spare man Viv always thoughtfully provided – this time a long-haired, big-boned sports reporter plucked without sufficient research from Jago’s office. And, with all the dinner finished, it now befell Belinda to adopt her perennial role at dinner parties – i.e. pointlessly sucking up to Viv.

‘That was such a good meal,’ she began. ‘I don’t know how you do it. I feel like I’ve eaten the British Library. I can’t even buy ready-cook stuff from Marks and Spencer’s any more, did I tell you? Every time I go in, I see all the prepared veg and I get upset and have to come out again. Even though I haven’t got time to prepare veg myself, I’m so depressed by bags of sprouts with the outer leaves peeled off that I have to crouch on the floor while my head swims. Has that ever happened to you?’

Viv shrugged. She refused to be drawn into Belinda’s domestic inadequacies. After all, they’d been having the same conversation for eighteen years. Also, praise always made her hostile – a fact Belinda could never quite accept, and therefore never quite allowed for.

‘I like your top,’ Belinda said.

‘Harvey Nicks. I went back to get another one, actually, but they only had brown. Nobody looks good in brown. I don’t know why they make it.’

Belinda wondered vaguely whether her own top-to-toe chocolate was exempt from this generalization. She didn’t like to ask.

‘What do you think about Leon for Maggie?’ Viv demanded.

‘The petrolhead?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, I can’t say he’s perfect. So far his only conversation is pit-stop records. He just told Maggie that Rembrandt wasn’t a household name.’

‘Yes, but Maggie is so lonely and desperate, she might not mind a diversity of interests.’

They paused to hear what was happening between Maggie and Leon.

‘Villeneuve’s a person?’ Maggie was saying. ‘Good heavens! So what’s the name of that bridge in Paris?’

Belinda raised an eyebrow, while Viv pretended not to hear. What a terrible life Maggie had. She looked pityingly at Maggie and saw how her own life might have turned out, if only she hadn’t responded so well to the nickname Patch. In her spare time, Maggie did therapy. When she got work, it was underpaid. It was common knowledge that she slept with totally unsuitable people. And when she went out to her friends’ house for a pleasant evening, looking more glamorous than the rest of them put together, they thoughtlessly paired her with a talking ape.

Sitting here, Belinda was caught in a common dilemma of women who compare themselves with others. With whom should she compare herself tonight? Beside Maggie, she looked rather accomplished. Whereas beside Viv, she looked like a road accident. Viv did dinner parties for eight without breaking stride. She had three sons with long limbs and clean hair who said, ‘Hello, Auntie Belinda, do you want to see my prize for geography?’ and ‘Guess what, I’ve got another part in a radio play.’ Viv dressed beautifully in navy. She attended a gym and went swimming. She canvassed for the Labour Party. And, just to give her life a bit of interest, she was the youngest ever female consultant anaesthetist of a major London private hospital.

Belinda took another reckless swig of wine. She used to say she had only two modes when it came to drinking: abstinence and abandonment. Looking at her fifth glass, she realized this system had recently simplified.

‘Jago got made executive features editor at the Effort.’

Belinda put down her glass with a clunk. ‘I didn’t know that.’

‘Last week. Bunter Paxton was kicked upstairs.’

‘Fuck.’

‘Dermot says it’s all part of his plan. I’m warming to Dermot. Are you?’

Belinda struggled to find the right thing to say. She was impressed, upset, mortified. Comparisons might be odious, but Viv and Jago were her own age. Identically her own age. She and Viv had started adult life with almost identical opportunities, from exactly the same spot, in fact: queuing for DramSoc at University College London, where they were subsequently cast as Helena and Hermia in A Midsummer Night’s Dream alongside Jago as Bottom. Viv was in medicine; she and Jago were in English. She had rather fancied Jago in those days. Hard to imagine now. Stefan was so good, so dear, the way he just fitted in. What a shame his first wife, the loony one in Malmö, had got custody of all their Swedish friends.

Viv nudged her to look at Maggie and Leon again. They had their heads together. ‘Anal?’ Leon was querying, his body language expressive of severe discomfort. He ran his hand through his long, greasy hair. ‘Are you sure?’

Belinda wrestled briefly with self-pity, and lost. Just look at what Viv had made of her life. I could have had that. She was beginning to remember why she didn’t enjoy going out.

‘And yet you go to all this trouble,’ she marvelled, waving a hand.

Viv sighed. Not this again. Not that Superwoman crap.

‘I’m not getting into this again, Belinda, I warn you. As I’ve told you a million times, my cleaning lady does everything in this house, and I don’t lift a finger. In fact, I’m sorry to say this,’ Viv’s voice rose, ‘but I wish you’d just shut up about it.’

Even in her drunken state, Belinda was startled by Viv’s high-handed, imperious tone. Just because you abjectly deferred to someone year after year, paying them superlative compliments, that surely didn’t give them the right to assume some sort of superiority, did it?

‘All right, keep your hair on,’ slurred Belinda, ‘I only said –’

‘Listen, I’m just going to say this to you, Belinda. Just this. Sack Jorkin. Lose Patsy. Boot Mrs Holdsworth.’

‘Is that all?’

‘That about covers it, yes.’

‘Should I move to Botswana as well?’

‘I’m just telling you how it looks from where I’m standing. And where lots of other people are standing too.’

‘Mrs H washes her hair with Daz, Viv. She lives on water boiled up from old sprout peelings. She hasn’t had a new scarf for ten years.’

Other chatter stopped abruptly as Belinda’s voice rose. Only Leon could be heard, saying, ‘Penile? In what way?’

Stefan intervened. ‘I agree with Viv you should award Mrs Holdsworth the Order of the Boot,’ he offered, with a smile. ‘Viv is right, as always. Mrs Holdsworth takes the piss and cooks her own goose long enough. Tell her to up stumps. A good wine needs no bush.’

Belinda was confused, and a bit resentful. She didn’t understand how sacking the cleaning lady would in any way improve her ability to give dinner parties. And she disliked it, naturally enough, when pleasant evenings with chums and husband turned Stalinist all of a sudden. She couldn’t remember the last time she saw it on a menu. Dessert followed by show trials; then coffee and mints.

‘You need people with a bit of initiative around you,’ said Viv. ‘There’s nothing supernatural about what I do. I just hive off bits of my life I don’t want. You could do that. I give mine to Linda. The cleaning lady. She does everything. She’s doing the washing-up right now. She did all the shopping and most of the cooking.’

Belinda nodded. ‘Linda,’ she repeated, dumbly. So deeply did Belinda believe in Viv’s domestic powers, she had always suspected Linda was an invention.

‘I’ve got no sympathy for you, Belinda. None whatever.’

‘Thanks.’

‘You know what I mean.’

Belinda sniffed loudly, and started to fish under her chair for her handbag. ‘Stefan, shall we go home soon?’

‘Oh for God’s sake, don’t take offence,’ snapped Viv. ‘I’m only thinking of you, as usual.’

Belinda noticed that the others had stopped talking, in order to listen better. She was not unaware that tiffs with Viv were becoming a regular feature of fun nights out. She tried a last-ditch compliment, to deflect attention. It didn’t work. ‘You’ve redecorated this room,’ said Belinda. ‘It’s lovely. All this white is very attractive.’

‘Well, we got sick to death of sea green. No one has that any more.’

Belinda experienced a familiar sensation, remembering her own sea-green bedroom, bathroom, kitchen, hall and array of fitted carpets. ‘All right,’ she said, seeing that flattery was getting her nowhere. ‘Assuming I can get someone brilliant like your Linda, how do I choose which bits of my life to give her? I wouldn’t know where to stop, I mean start.’ Belinda thought about it, and felt a bit sick. ‘No, I was right the first time. I wouldn’t know where to stop.’

Viv arranged some wine bottles in a line. She was resisting the urge to hit Belinda. ‘Belinda, just imagine you had the choice. Would you rather sit in your study reading about – what is it you want to read about all the time?’

‘Doubles. Like Dr Jekyll and Mr—’

‘OK. Would you rather sit in your study reading that ridiculous old nonsense, or – I don’t know – keep the loo seat free from nasty curly pubes?’

Belinda masticated a truffle. It tasted wonderful, like violets. It took her mind off the hurtful implication that her curly pubes were nasty. ‘All right,’ she said warily, ‘I’ll replace Mrs Holdsworth. But I’m keeping Jorkin and Patsy.’

‘It’s your funeral,’ said Viv, and getting up, she started to clear dessert plates.

Stefan leaned across. ‘How about we ask this Linda if she can work for us too? She doesn’t work for you every God’s hour, I think?’

It was the most innocent of questions. But had they heard a suicidal gunshot from the downstairs cloakroom the effect could not have been more Ibsenesque. Viv stood up and knocked over her chair; Jago shot her a meaningful glance; Viv’s eyes widened in anger as she turned to face Belinda.

‘If you do that,’ she said, ‘I warn you, I’ll never speak to you again.’

Belinda laughed. They all did. Maggie even clapped. But Viv was serious. ‘Take my cleaning lady, you ungrateful bitch—’

‘Viv, we’re only talking about a cleaning lady! This is ridiculous.’

Jago chipped in. ‘I know it sounds crazy. Linda’s more than a cleaning lady, that’s all. She has a way of making herself indispensable. And let’s just say—’

‘That’s enough, Jago.’

Belinda fell back in her chair, exhausted. ‘I don’t get it,’ she confessed. ‘I’m sorry, but I don’t get it.’

‘Coffee?’ said Viv.

‘I’ll help,’ offered Dermot.

Belinda and Stefan pulled faces at one another.

At the other side of the table, Leon presented Maggie with a perfect, tiny origami racing car, folded out of a napkin. ‘All right,’ he said. ‘Tell me what’s anal about that.’

Belinda woke up suddenly. How long she’d been nodding at the table she didn’t know. Noticing Viv was missing from her side, however, she stood up to find her but lurched unexpectedly and almost sat down again. She must be drunk. Jago was now telling Leon a familiar joke about a Jewish widow addressing her husband’s ashes in her hand. ‘“Remember the blow-job you always wanted, Solly?”’

Trying for a second time, she got up successfully and propelled herself towards the door – at which point, she heard Viv on a darkened landing, whispering angrily to Dermot.

‘I wouldn’t mind but she owes everything to me,’ Viv was saying.

‘Belinda’s a real nobody,’ Dermot agreed. ‘A nothing of a nobody.’

Belinda leaned against a wall and listened.

‘I introduced her to Stefan. It was all me. But she’s never content.’

‘Some people suck the blood out of you. They’re vampires. I see it every day, people taking the credit when everything they do is my idea. You have to tell them how great they are all the time. Belinda just takes and takes.’

‘You’re right. People only ever want to talk about themselves. We’re just mirrors they see themselves in. Mirrors in which they flatter themselves.’

Dermot’s voice became tender. ‘You shouldn’t be bothering with vampires, Viv. You should think only of your lovely, lovely self. I know I shouldn’t say it, but Viv, I mean this, you’re such a good person.’

Belinda held her breath and grimaced. Dermot clearly didn’t understand that flattering Viv made her vicious – sometimes to the point of violence. But something else happened. Because Viv evidently caught a sight of herself in Dermot’s flattering mirror.

‘Am I?’ said Viv.

‘You’re so good, so fine. In fact, I admire you very much.’

‘You do?’

‘I’ve got no reason to say this, incidentally.’

‘I know.’

There was a pause while the loathsome Dermot thought of some more sugary things to say. Belinda was astonished.

‘You’re fantastic,’ he continued.

‘Thank you.’

‘And, you know, I love just talking about you freely like this, without you feeling you have to say anything reciprocal about me.’

‘Wow.’

Belinda backed away to the kitchen, fearful of overhearing the inevitable culminating squelch of a kiss in the dark. Her emotions were mixed, and her demeanour unsteady, but her intention was perfectly clear. As she made her way to the kitchen, she had one single thought. She would hire Linda. Ungrateful vampire bitch that she was, she was determined to take, take, take. Petulance was an emotion that held no fears for Belinda. If Viv thought so badly of her already, then stealing her cleaning lady was obviously the very least she owed her reputation.

None of Viv’s friends had come face to face with Linda, so it was quite a surprise that she looked like Kylie Minogue. Belinda had imagined a composite of stereotypes. Lumpen librarian in a thick skirt and frilly blouse. Rubber gloves in primrose yellow. Intimidating. Carrying a bucket. A Cordon Bleu, perhaps, pinned to her sensible apron.

But the woman reading the magazine in the kitchen was in her early thirties and pretty. She wore fitted jeans and a spotless white T-shirt, with strappy shoes. Her auburn hair was thick and long, and when Belinda noticed her hands – small and clean, with nails beautifully polished, like mother-of-pearl – she felt an unaccustomed jolt of envy.

Hearing Belinda in the doorway, this youthful vision of unlikely cleaning lady assumed it was Viv. ‘I wish you’d let me do the rest of it, Viv,’ she said, indicating rather a lot of washing-up on the kitchen surfaces, ‘but I have to say I’m enjoying this Lancet. Oh, hello.’

Something about this greeting puzzled Belinda but, on the other hand, she was so fuddled by drink she could barely remember her mission.

‘Psst. Are you Linda?’ she hissed.

Linda was evidently amused. ‘Yes,’ she hissed back, exaggeratedly.

‘Shh,’ said Belinda. ‘I’m Mrs Johansson, but you can call me Belinda.’

‘All right, Mrs Johansson.’

‘Listen, Linda. I’ve got something to ask you.’ Belinda staggered slightly. ‘I want to ask you to work for me.’

‘That’s nice,’ said Linda. ‘I wondered when you would. That’s a lovely top.’

Belinda looked down at it, but couldn’t focus. ‘Are you sure? It’s not black, you know. It’s brown.’

Linda smiled.

‘Shall I come tomorrow?’

‘Wow, yes. If you’re sure. Blimey, that was easy.’

Belinda turned, and steadied herself in the doorway. ‘Dr Ripley may not be happy about this,’ she added, over her shoulder. She felt she ought to mention it.

‘That’s OK,’ said Linda.

‘Really?’

‘Leave it to me. Are you all right?’

‘I’m OK,’ said Belinda. ‘Thanks.’

Stefan tried never to argue with his second wife. Things had gone badly enough with the first one. But that night, as he drove home late through South London, he was impatient. Because for some mad reason Belinda had gone behind Viv’s back and attempted to steal her cleaning lady. Moreover, she’d informed him as if he would be pleased.

‘This underhandedness is a rum go, Belinda,’ he said. ‘Honest to goodness, I feel I may blow my top.’

‘I’m sorry,’ she said. Stefan drove too fast when he was angry. She’d only said Viv was a cow who regularly pierced her heart with a hundred poison quills, and now they were going to get killed jumping traffic-lights.

‘Listen. Viv is a lovely person. Your behaviour beggars description.’

‘No, Stefan. You’re wrong. There’s a subtext. Underneath all Viv’s loveliness towards me she actually hates me and she wants me dead. It’s a sibling-y kind of thing.’

‘You hate her, more likely. Because you make a meal of everything and to her it’s a doodle.’

‘Doddle.’

They stopped too late at some traffic-lights, and the car slewed with the braking force, jolting both of them forward. Belinda judged that this was not the right moment to mention how much she disliked Stefan’s driving.

‘Tell me you won’t hire this Linda.’

‘I can’t. Besides, Stefan, it was your idea. You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.’

He put the car in gear, revved high, and let out the clutch so that they shot forward at forty miles an hour.

‘Belinda, I tell you straight. It is not just the Linda thing. I am fed up to the back teeth, you are coming a cropper and I will not fiddle while Rome burns. Maggie says to me tonight, “Belinda is wedded to her work, not to you, Stefan.” You cry on the telephone to the man. I don’t want you going loco, Belinda. It happened to me before.’

Belinda frowned. What did he mean, it happened to him?

They cornered with a squeal of rubber.

‘Let’s leave Maggie out of it. She’s got her own agenda.’

Stefan slowed for some lights, and Belinda took a deep breath. ‘Look, I’m not going loco, as you put it. It’s just that nobody understands me except Neville.’

Stefan swung the car into Armadale Road, spotted a parking space and braked abruptly. It was an excellent spot, twenty yards from the house. He reversed the car into the space, turned off the engine, extinguished the lights. And putting his hand on Belinda’s arm, he pulled a solemn face.

‘Belinda, this isn’t like you. You are breaking up.’

‘For heaven’s sake, she’s only a cleaning lady.’

She kissed him hard, running a hand round his collar, smelling his hair. She’d never been addicted to a person before Stefan.

‘You’ll like her,’ she said. ‘Once you’ve met her, I promise you. You won’t be able to help it. And Viv will get over it. The cow.’

Back at Jago’s, at three a.m., Viv crept downstairs to check the burglar alarm and found Linda sitting in the dining room in the dark, a book of Viv’s old photos in front of her on the table.

‘Linda?’ But Linda did not look up.

Viv switched on a table lamp and coughed.

‘Viv!’ Linda said pleasantly. ‘What a nice evening. Your friends are so interesting.’

‘Well, Leon was dreadful. Honestly, Jago is such a desperate judge of character. Do you know, after all that boring Brands Hatch nonsense, it turned out he doesn’t drive? Maggie had to give him a lift to Wandsworth Town. I don’t know why I try so hard for people, they never co-operate.’

Viv tidied a few things while Linda watched. The light-bulbs hummed. She smoothed a curtain. She had something important to ask. Talking to the cleaning lady, she had none of the commanding manner she adopted with Belinda. She seemed almost deferential.

‘Linda?’

‘Mm?’

‘You know how I depend on you?’ Viv laughed nervously. ‘I had a scare this evening. Did Belinda speak to you? You wouldn’t leave us, not after everything?’

But, as Linda turned a page and studied the pictures, Viv’s heart sank. She had hoped Linda would do the cleaning-lady equivalent of running into her arms. Instead, it was like asking, ‘You do love me, don’t you?’ and knowing after a few, short, vertiginous seconds that an affair was all over. The longer you have to wait for an answer to that sort of question, the more certain you can be that the answer is not the one you want.

‘How old is Stefan?’ asked Linda.

‘What? Oh, fifty-one.’

‘And you introduced him to Belinda.’

‘Yes. My sister met him at Imperial.’

Viv joined Linda to look at the album. It included fuzzy colour pictures from the old DramSoc days. Viv perused the page. Their faces were almost unrecognizable, but nothing had changed, really. At college, Maggie was disastrously involved with a succession of goaty lecturers. Belinda complained all the time about the timetable. And Viv organized an excellent summer outing, to which Jago brought along some useless dickhead they never saw again.

‘Are you going to Belinda?’

‘I thought I would, yes. Oh, Viv, don’t look like that. I’m so sorry. But at the end of the day, I’m only your cleaning lady!’

‘How can you say that?’ Viv gasped.

Linda took Viv’s hand and squeezed it. It would have been clear to any onlooker that the usual relationship between employer and cleaning lady (‘How are the feet?’ ‘We need more Jif’) had been long since outgrown.

‘It’s gone a bit mad here,’ said Linda.

Viv laughed. ‘You can say that again.’

She thought about it, took a deep breath, and resolved to be brave. ‘So. How are we off for J-cloths?’ she asked.

Linda smiled at her gratefully. ‘How the hell should I know?’ she retorted.

At which the two of them laughed and laughed in the small hours until they had to hold each other up. At three a.m., Belinda woke Stefan by turning the light on. She’d had a dream she needed to write down. And since he was now awake, she was quite keen to tell him about it, too. And also to treat him to an instant analysis, as she always did. In this dream, she said, she’d been bundled up in the bedclothes and placed in the washing-machine by an unseen hand. ‘It was an unseen hand,’ she said, significantly. ‘But I think we know whose it was. She was singing “I Should Be So Lucky”.’

Stefan shrugged.

‘Kylie Minogue,’ she explained. Belinda popped to the loo, and came back, over-confident that she had captured her husband’s attention. She shook him awake to continue.

Belinda often had premature burial dreams, but this one was different. No shovel, no grit. No bone-white fingers poking through the black earth. No, this was the opposite of the Gothic nightmare. Instead of feeling frightened and stifled in this one, she’d had rather a wonderful time. The water was warm and sudsy, something like amniotic fluid but with bright blue enzymes for a whiter white. And the rhythm was very comforting. ‘Slosh-to-the-right, two, three, slosh-to-the-left, two, three. Over, over, over, over, slosh, slosh, slosh.’ It reminded her of perhaps the greatest joy of her infancy – the bathtime game her father had played with her, safely cradling her in strong arms, then gently drawing her the length of the bath while singing the old music-hall song, ‘Floating down the river, on a Sunday afternoon’.

Stefan closed his eyes. As a scientist, he was more interested in the physiology of dreams than their nostalgic evocations.

‘No chance of you drowning, my dear? I say it helpfully, you understand.’

‘No, no. I didn’t even struggle. It was so cosy. Sloshing about. I just tapped on the milky glass from time to time – “Hello? Excuse me! Hello?” – because life was going on outside, and you were out there, Stefan, eating a bagel. You didn’t even seem to notice I’d gone.’

‘Which cycle were you on?’

‘Special treatments.’

‘Oh, good. I have always wondered what that was for.’

Belinda happily snapped shut her dreams notebook and turned the light off. ‘You know what this means?’

‘Something about the womb?’

‘No, it means Accept the Cleaning Lady. That’s good, isn’t it? Even my subconscious says it’s a good idea.’

‘Well, I’m going up,’ said Viv. ‘Thanks again for everything tonight. It will be odd not to make a list for you.’

‘It was all a sham, Viv. It’s time for you to admit it. You are Superwoman. We talked about this. We knew it couldn’t go on.’

Viv’s chin wobbled. ‘I’m not Superwoman,’ she said.

Linda put her hands on Viv’s shoulders. ‘Yes you are.’

And Viv jumped, as if she had been stung.

‘And what was the spin like?’ said Stefan.

‘Oh, that’s a point.’

Belinda turned on the light again as Stefan groaned.

‘What is it now?’

‘I woke up before the spin.’ She made a note. ‘Perhaps I’ll have to have the spin another time.’

When the lamps were finally out, they lay quietly in the dark for a minute. Stefan’s pre-sleep breathing had a little rhythmic squeak in it, a whistle in his nose. Belinda listened to it comfortably, happy. The room was otherwise perfectly still, perfectly quiet.

Hiring a new cleaning lady had been such a small decision, yet it had changed everything. On her way to the bathroom she had spotted a heap of laundry at the top of the stairs but it had not said, ‘Remember me?’ Instead it had asked rather excitedly, ‘When does she start? When does she start?’

Something else had changed, too, although at first she couldn’t put her finger on it.

‘Neville?’ she whispered, at last. In her abdomen, a spotlight swivelled around a deserted Big Top, finding only sand and sawdust, and bits of torn paper streamer. ‘Neville, are you there?’

Three (#ulink_8705aa6e-57ef-5038-9be1-6af6c1a62128)

Belinda was right to say that Maggie had her own agenda. In fact, Maggie’s agenda was about as well disguised as a Centurion tank in a hairnet. Thus, when she told her oldest friend Belinda, ‘You work too hard’, what she really meant was ‘You don’t spend enough time listening to my problems’. When she said to Stefan, ‘Belinda cares only about her work,’ what was clearly imported by this treachery was ‘I’ll always love you, Stefan, I want to have your babies, and it’s not too late’. Telling Leon she thought Villeneuve was a bridge in Paris translated as ‘You’re a dreadful motor-racing bore and I can’t believe I’m listening to this.’ Indeed, the paradox of Maggie’s life was that the more rudely she semaphored her real message, the more her friends felt it polite to take her words at face value.

When she woke on Wednesday in her Clapham flat, the morning after the dinner party, it surprised her to find that Leon was still there. She assumed it was Leon, anyway. An enormous naked male body was sleeping face down diagonally in her four-foot bed, which was as unprecedented as it was uncomfortable. Blokes who went to bed with Maggie were, of course, not literally ‘all the same’, as she would sometimes complain, but they certainly shared many tendencies, and one of these was the quite strenuous avoidance of sleep. As if obeying house rules pinned to the door, they would resolutely roll out of Maggie’s bed and breast the cold night air without so much as a cup of tea or a post-coital cuddle. It was a strange, inexplicable nocturnal-urgency syndrome she had often remarked on.

‘Gotta go,’ they’d say, hopping about zipping their trousers and cleaning their teeth at the same time, like characters in a bedroom farce. ‘Unfortunately, I’ve got a very, very early appointment in the morning. Is this soap scented? It’s not bluebell or something?’

‘All my conquests are either undead or office cleaners,’ she would tell her mates, by way of brave humour. But in fact her conquests were fathers of small children, of course; fulfilling some sort of universal genetic imperative to cheat on the wife during the first year of parenthood. Maggie made a point of meeting the wives of her Undead Office Cleaners as soon as possible – not to cause trouble but simply to prevent her from becoming ‘the other woman’. Meeting the wife had this curious way of dispelling any self-deluding fantasies about adultery. Before you met the wife in the living flesh, you could imagine you were the real person and the wife was the anonymous incorporeal phantom. Whereas after you met her, the mirror swivelled to offer a truer perspective, in which the wife was the real person and you were the lump of garbage.

Anyway, ask any of her friends, and they could tell you Maggie’s exact emotional pattern on these wham-bam occasions, because she’d described them often. As the taxi roared off at two a.m., she would wave gaily from the doorway in her dressing-gown, feeling all jelly-legged and warm. Then she’d go back to her tousled bed with Ariel and Miranda (the cats), Hello! magazine and a hot cup of something brown and chocolatey called Options (nice touch), and as she brushed the condom wrapper from the sheet, she’d tell herself that no scene could better sum up the freedom of modern womanhood.

Oh yes, Simone de Beauvoir would be so proud. Look, all that money, yet Barbra Streisand still had a hideous home! On the verge of sleep, she might decide it was high time a sexy woman of her calibre had her navel pierced. And then, seemingly a minute later, she woke alone in broad daylight. The room looked dusty; her pillow was caked in dribble and cat hair; she felt ravaged and cheap. The man in question was by now several miles away playing with baby in the bath, and would doubtless ignore her the next time they met, making her feel she’d been punched in the stomach. ‘What have I done?’ she would wail, then burst into tears and phone Belinda.

‘Shouldn’t you be getting home?’ (translation: ‘Get out of my house’) she asked Leon. She kicked his bum, which wobbled. Although she couldn’t now remember all the details, it had not been a terribly successful night, and it was annoying to find him still here. Evidently in Formula One they can refuel a car in under seven seconds – a statistic that was now proving hard to dislodge from her memory. Good grief, she still had her bra on.

Quite rightly it offended Maggie that while she was fit, pretty, clever, a bit famous and had screen-tested for Titanic, she’d still allowed herself to go to bed with Leon. It was so obvious she was too good for her sexual partners, yet strangely, there was no system of justice governing such matters, no god of eugenics who intervened on her behalf. ‘Stop!’ a voice should have said, as Leon gently placed his big paw on her neck in the car. ‘This coupling goes against nature, and must not proceed. This woman is reserved for clever, attractive males who write poetry and stuff. Kenneth Branagh, at least.’

But Maggie knew that the voice saying, ‘Stop!’ would never be hers. While she waited for Stefan to stop loving Belinda, she made the best of things; responded to advances from all directions; made quite a few advances of her own. Not that she was blind to male imperfections; far from it. But in sexual matters, you are often obliged to take your partner at his own estimation, and it’s a sad fact of life that many ugly, bald men look in the mirror and see Kevin Costner. Consequently, Maggie’s romantic career had encompassed sexual partners who, in former, more brutal, God-fearing eras, would have been stoned to death by mobs.

Leon snored and flapped a big white arm, but otherwise showed no sign of life, so she got up. She could have snuggled down, growled an erotic Murray Walker impersonation to rouse his ardour (she was good at accents). But on second thoughts, a bacon sandwich was more appealing. It was nearly lunch-time. So instead she made unrestrained noise having a shower, getting dressed, playing an oldies programme on Radio Two, and singing. She switched off half-way through Abba’s ‘Take A Chance On Me’ – it reminded her too painfully of her first-in-line feelings for Stefan.

She checked Leon wasn’t dead, of course. Remembering her duty as a hostess, she held a mirror to his lips until she saw vapour. But he wasn’t dead, and he wouldn’t wake up. So, humming ‘Gimme, Gimme, Gimme (A Man After Midnight)’, she left him a note with directions to the Gemini corner café, and went out.

At college, Stefan was having coffee with Jago in the library canteen. They had arranged it the night before, when Jago overheard Stefan on the subject of killer tomatoes. ‘We’ll do a genetics supplement and you can be consultant editor,’ he’d told Stefan. ‘I’ll see you at eleven.’ The trouble with journalists (as Stefan had often said to Belinda) was that they couldn’t help regarding you not as a person but as a source.

‘I need some Swedes quick,’ Jago might ring up to ask, mid-thought in his scurrilous weekly column in the Effort. No preamble, of course. Busy man, Jago. Part of his charm.

‘For sure. Ingmar Bergman, August Strindberg, Björn Borg.’

Jago could be heard tapping his keyboard in the background. ‘B-U-R-G?’

‘Well, B-E – which one?’

‘All of them. You tell me.’

‘Ingmar is B-E-R-G, August is B-E-R-G, and Björn is B-O-R-G. The reason for such a high incidence of the name Berg and its variants, of course—’

‘Great. You sure?’

‘Yes.’

‘One more Swede who isn’t a Berg, in case the subs don’t take my word for it?’

‘Abba?’

Four more emphatic taps.

‘Good man, gotta go.’

‘That was Yago,’ Stefan would tell Belinda, still holding the dead receiver in his hand.

‘How did I guess?’

The phrase ‘need-to-know basis’ had been invented for Jago. He was only interested in anything when he needed to know. Tell him a fact at an inappropriate moment (when he wasn’t writing an article, or commissioning one) and he literally screwed up his face to prevent it getting in. He was a tabula rasa with a straining Filofax, and other people were the fools who stored primary material until he came along to nick it. Not that your help would earn you any loyalty from him, let alone thanks. You could help him a hundred times, and he’d stitch you up on the hundred and first. The curious thing was, when Jago looked in a mirror he saw George Washington.

‘So how big is this supplement in the Effort?’ Stefan sighed, playing with his specs in a professorial manner.

‘Twelve pages. Minus ads. That leaves room for about three articles and a dozen pics.’

‘Why do you think I’ll contribute to it?’

‘Um, because if you don’t, I’ll go straight to Laurie Spink?’

Stefan smiled but didn’t reply. Laurie Spink made television programmes about genetics. He had a column in The Times.

‘OK, forget that Spink blackmail thing, that was tacky. If you do this for me, Stefan, I promise never to tell Belinda how I know you’re not a natural blond. What more can I say? Copy is by next Friday. A thousand words on anything. Is there a gene for monstrous boobs? Could you look for it between now and next Friday? I’m only thinking of the picture desk.’

‘Do people actually read these supplements, Yago? I’m afraid I am a doubting Thomas.’

‘Well, I’m glad you asked that. Research shows that, yes,’ he screwed up his face, as if trying to remember the exact figure, ‘one million, two hundred and twelve people read these supplements.’

‘But really they’re thrown in the bin?’

‘In a New York second.’

Stefan checked his watch and stood up. Jago took the hint. Besides, he’d arranged to call Laurie Spink in five minutes’ time. ‘I’ll be off,’ he offered. ‘So you’ll do it?’

Stefan shrugged. ‘No. It’s not really me, I think.’

‘Of course it’s you!’

‘I’m not a writer, Yago.’

‘No problem, big guy. We’ll write it for you in the office. I’ll ghost you. Happens all the time.’

‘Monstrous boobs may be for some the cat’s pyjamas, but – no.’

‘Stefan, why are you doing this to me?’

‘Because it’s a free country.’ Stefan shrugged. ‘East is east and west is west. Genetics is not all beer and skittles.’

Jago was confused, but more than that, he was hurt. Journalists always pout if you puncture their plan, even if they’ve only had the plan for the last ninety seconds.

‘Why do you call it copy?’ Stefan asked.

Jago looked puzzled.

‘Call what copy?’

‘Copy. I mean, the writing is supposed to be one-off, I think?’

‘Well, I wouldn’t go that far. This is journalism we’re talking about.’

‘I mean, would you ever say, “Gosh, hey, this is very original one-off copy”?’

Jago had had enough. ‘If I ever said, “Gosh, hey,” at all, I’d lose my job, Stefan. As should you, I might add.’

He strode out of the canteen, and extracted his mobile phone from an inside pocket. Stefan had just completely wasted his time. What a two-face! ‘Gosh, hey, this is very original one-off copy!’ he said, with Stefan’s careful accent. He couldn’t wait to get back to the office to try that one on the guys.

Belinda spent the morning writing an imaginary riding-in-Ireland piece for Jago’s paper, and wondering what had happened to Neville. He was not his usual bouncy self. Even when the phone rang and it was her mother (eek!) there was only a twitch or scuttle from Los Rodentos. Someone phoned up to ask Belinda to appear on radio (she declined, but felt agitated); she remembered Stefan’s birthday was next week; the usual pressures most certainly applied. But no trampolining by small furry bodies. The rats were on a go-slow. Ever since she’d decided to hire Linda, she’d felt like the proverbial sinking ship. ‘Psst, Neville,’ she whispered. ‘Are you all right?’ Not a scuttle; not a squeak. Life was odd without his wheeling and bouncing. She pictured him with little round spectacles, like John Lennon. But no matter how much she hummed ‘Imagine’ to encourage him, he simply wasn’t interested.

Belinda always had a marvellous time alone with her imagination. Having invented quite a good travel piece, if she said so herself (‘Wind and soft rain whipped the ponies’ fetlocks; my hat was too tight, like an iron band’) she was now plotting the next Verity novel, Atta Girl, Verity!, in which Verity’s impoverished mum would break the terrible news that she couldn’t afford to stable Goldenboy at the Manor House any more – or not unless Verity took a backbreaking after-school job pulling weeds in Camilla’s mummy’s seven-acre garden.

How she enjoyed visiting pain and anguish on Verity, these days. She beamed as she considered Verity’s fate. Ho hum. By the rules of such fiction, Verity must, of course, come back from a perfect hack on Goldenboy, and be rubbing him down with fresh-smelling straw when in the distance, eek! splash!, Camilla falls into the ornamental fishpond! Run to the rescue, Verity! Don’t care if your plaits get wet! Recover Camilla unconscious, apply life-saving techniques, and after a feverish period awaiting Camilla’s recovery, receive as reward (wait for it) free stabling for the rest of your life! And not forgetting double oats for good old Goldenboy!

The children’s book world was mainly supplied these days with grim stuff about discarded hypodermics, but Belinda knew her own smug little readers would lap up the free stabling plot all right, mainly because they had already proved themselves stupid with no imagination. How easy they were to manipulate, these little princesses. Psychoanalysis might never have been invented. ‘Camilla cuts off Verity’s plaits,’ she wrote now, mischievously. ‘Verity caught cheating in the handy-pony. Shame increases when V investigated by RSPCA; maltreatment of G Boy exposed on national TV by Rolf H. V’s mother seeks consolation in lethal cocktail of booze and horse pills, and is shot by vet. Camilla wins Hickstead.’

Just then a key turned in the front door. Mrs Holdsworth? Belinda felt stricken. She’d been so busy torturing Verity! What was the etiquette for sacking a cleaning lady? Did you let her do the cleaning first, or what?

‘Only me,’ called Mrs H, coughing as she slammed the front door, and struggled out of wellingtons.

Belinda stayed paralysed at her desk, panicking. ‘Hello!’ she called, and waited.

‘“Come into the garden, Maud,”’ sang Mrs H, coughing between words. ‘“For the black bat night has—”’ Here a great explosion of phlegm-shifting, culminating in ‘God almighty, Jesus wept.’

She popped her grey head round the study door, fag in mouth. Here goes, thought Belinda, then noticed that Mrs H’s left arm was suspended in a rather grubby sling.

‘Don’t fucking ask,’ said Mrs Holdsworth gloomily. ‘Doctor says six months. I tell you what for nothing. My fucking brass-polishing days are over.’

‘That’s awful,’ sympathized Belinda. ‘And when they’d hardly begun. What a shame. I’m sorry.’

‘So am I. No grip, you see.’

‘I’ve been thinking—’ Belinda began.

‘Fucking stairs are the worst, of course.’

Mrs H scratched her knee through her overall, using her one good arm. Recollecting that there were three floors to her house (plus attic), Belinda didn’t see how an injured wrist stopped you from going upstairs, but she said nothing. Asking Mrs Holdsworth to elaborate on an intriguing statement was a mistake she’d regretted on too many occasions, and she now had a policy of restricting herself to a noncommittal ‘Mm’ wherever possible.

‘Mm,’ she said now, with as much of a funny-old-world tone as she could manage.

Mrs H continued to stand in the doorway. It always grieved her to spend less than half of her allotted three hours telling people how long it was since she bought a scarf. She tried again. ‘Bleeding great ’urricane on the way, apparently.’

‘Mm.’

‘That Salman Rushdie was in the butcher’s again. I said to him, “Very good, mate. Disguising yourself as a pork chop, are you? That’s fucking original.”’

‘Mm.’ Belinda pretended to be deeply engrossed in her notes.

‘My boy says he’s written a new book called Buddha Was a Cunt. Is that true?’

In the café, Maggie read last week’s Stage from cover to cover, filling time before her therapy appointment at two p.m. Maggie had run the gamut of therapy over the years. She’d done Freudian twice and Jungian three times, but had so far avoided Kleinian because Belinda had once said, ‘What, like Patsy Cline?’ which had somehow ruined it. Belinda had an awful way of belittling things that were important to you, by saying the first thing that came into her head. Kleinian therapy would now only involve singing maudlin I-fall-to-pieces country songs, which was what Maggie did at home anyway without paying.

Nowadays Maggie was working with a new therapist, Julia, who was the best she’d ever had. The idea was to work on isolated problems, and correct the thinking that led to inappropriate behaviour or beliefs. For example, Maggie had a problem about other people being late. ‘So does everyone,’ pooh-poohed Belinda. ‘Not like me,’ said Maggie. And it was true. Maggie not only got angry and worried as the minutes ticked by, but after a while she started to imagine that the other person was not late at all. He had actually arrived on time, and was standing at the bar or something – but that she had completely forgotten what he looked like.

‘But he’d recognize you?’ Belinda objected. ‘So you’d still meet up.’

No, said Maggie. Because it was worse than that. He’d forgotten what she looked like, too.

‘That’s mad,’ Belinda had said, helpfully. ‘You should never have become an actress if you can’t handle the odd identity shift, Mags.’

Luckily, the therapist took a more constructive approach.

‘Now, since this non-recognition event has never occurred in reality,’ said Julia, ‘we must uncover the roots of your irrational anxiety, which I’m afraid to say, Margaret, is your sense of total unlovability. It’s not your fault. Not at all. Your needs were never met by your parents, you see.’

‘You’re right.’

‘You were made to feel invisible by those terrible selfish people, who should never have had children.’

Maggie sniffed. ‘I was.’

‘They looked right through you.’

Tears pricked Maggie’s eyes. ‘They did.’

‘Did they tell you to stop dancing in front of the television, perhaps?’