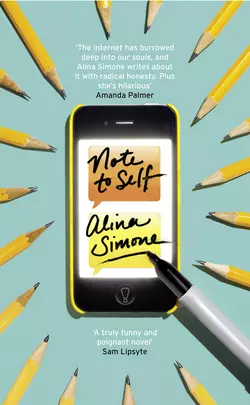

Note to Self

Alina Simone

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 465.10 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A darkly humorous reckoning of our modern condition – spam mail, internships, frenemies and hype – and the story of Anna’s quest for the meaningful life she knows she deserves.Are you a real person?Anna Krestler has been fired and needs a new job. What she doesn’t need is to check her Gmail account for new messages, or click-through to a blog on underwear that prevents cameltoe. But Anna is addicted to the internet, and no matter how much her life-coach bullies her, she can’t resist the lure of the next link.Everything changes for Anna when she chances upon a particularly cryptic online advert. Her reply is the gateway to an existential adventure that sees her swallowed whole by New York’s avant-garde art scene and the strange world of experimental cinema.Anna will do anything to impress Taj, the enigmatic filmmaker, and gradually he begins to direct every aspect of Anna’s life. But is Taj for real anyway? Is Anna? And what’s better? To be totally, obviously real, or really obviously fake?