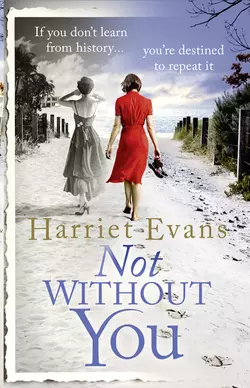

Not Without You

Harriet Evans

If you don’t learn from history . . .You’re destined to repeat itNot without you, she’d said. And I’d let her down…Hollywood, 1961: when beautiful, much-loved movie star Eve Noel vanishes at the height of her fame, no-one knows where, much less why.Fifty years later, another young British actress, Sophie Leigh, lives in Eve’s house high in the Hollywood Hills. Eve Noel was her inspiration and Sophie, disenchanted with her life in LA, finds herself becoming increasingly obsessed with the mystery of her idol's disappearance. And the more she finds out, the more she realises Eve’s life is linked with her own.As Eve’s tragic past and the present start to collide, Sophie needs to unravel the truth to save them both – but is she already too late? Becoming increasingly entangled in Eve’s world, Sophie must decide whose life she is really living . . .

Not Without You

Harriet Evans

Table of Contents

Cover (#u738e6ccc-53fa-5982-b0f3-ea356d59e416)

Title Page (#uf4429169-2d09-5f79-a41d-eafe0526db45)

Prologue (#u0831f5b0-4141-5fa1-b5c2-b4bb8a2bd398)

Part One (#u54dac358-096e-5061-bd6a-004fa4831045)

Chapter One (#u8d266610-4020-5baf-bab2-36de67191d4d)

Chapter Two (#u5cefda29-5901-574d-85f6-7709a83ab5a0)

Chapter Three (#ua03e13f2-c52c-5bf7-aa1a-be0b0a71445a)

Chapter Four (#u8048106d-6dda-5c99-9c14-a7051b675a2b)

Chapter Five (#u4d9f147c-ec9f-5e1e-a51a-1cad98fb849b)

Chapter Six (#u7439e3cb-6b2a-5e9c-91fb-427d5b705f69)

Chapter Seven (#u57d6027a-a3f8-5c2d-b4b0-46763f2eaa4f)

Chapter Eight (#ua127bc24-c0c5-5020-84fa-cc360734dd1c)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Harriet Evans (#litres_trial_promo)

Read on for an extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE

A BRIGHT SPRING day, sunshine splashing yellow through the new leaves. Two little girls stand on the banks of the swollen stream, which rushes loudly past their small feet.

‘Come on,’ says the first. ‘There’s magic coins in there. Gold coins, from the elves. I can see them glinting. Can’t you?’ She pushes the short sleeves of her lawn dress up above her shoulders; a determined imitation of the men they see in the fields beyond, backs curved over the soil. Her brown hair bobs about her head, sun darting through the bouncing curls. She grins. ‘It’ll be fun. Don’t listen to them.’

The second one hesitates. She always hesitates. ‘I don’t know, Rose,’ she says. ‘They said it’s dangerous. All that rain … Father said you weren’t to do it again. He said you’d be sent away if—’

‘You believe them, don’t you.’ Rose crosses her arms. ‘I’m not doing all those things they say I do. They’re making it up. I’m not bad.’

‘I know you’re not.’ The younger one mollifies her sister.

‘I didn’t mean to break the jug. Something happened to me, everything went black, and I didn’t know where I was.’ She bites her lip, trying not to cry. ‘I don’t like it. I want Mother and she tells me I’m bad when I do.’

A tear rolls through the brown film of dust on her cheek. They’re both silent, under the old willow tree. Eve speaks first. She points at the gold coins, swelling and then vanishing in the water’s rush.

‘Come on, let’s try to get them, then.’

‘Really?’ Rose’s face brightens.

‘I’ll do it if you do.’ She always regrets saying that.

Rose immediately clambers in. ‘I’ll go first.’

Eve watches her doubtfully. ‘It’s awfully strong. You won’t get swept away?’

‘I told you, it’s fine. Thomas does it all the time,’ Rose says, leaning over, confident again now, and Eve relaxes. Rose is right, of course. She’s always right. ‘There it is. I’m sure it’s gold! I’m sure the elves were here – their kingdom is right under the ground, ancient noble soil!’ She claps her hands. ‘Golly! Imagine if it is! I told you, little Eve. You mustn’t worry – they won’t send me away. I’m not going anywhere.’

This is the last image of her that Eve remembers. Standing like a miniature pirate, legs planted firmly in the stream. ‘We’ll always be together. I’m going to be a famous explorer. You’ll be a famous actress. We’ll do different things for a couple of weeks at a time. I’ll see some polar bears and … pharaohs. And you’ll do plays and dine with Ivor Novello. Then we’ll meet up in New York, under the King Kong building. You’ll have that delicious robe on, the one Vivien Leigh was wearing in Dark Journey. ’Member?’

Eve nods. She joins in the game, smiling. ‘Oh … yes. We’ll stay in beautiful hotels and we’ll drink milk stout.’ This was a great obsession of theirs, after Cook had told them it was her favourite tipple. But Cook had left, like so many of the servants lately. Gone in the night, shouting, ‘I’ll not stay here with that thing in the house!’

Rose nods. ‘We’ll always be together, Eve, like I say, ’cause I’m not going anywhere, not without you.’

And she screamed, then jerked forward. I can still see it, as if something else, an evil spirit maybe, was knocking her over from behind.

Should I have stayed? Or gone for help and left her prostrate in the water, eyes wide open, small body rigid? I still don’t know to this day if I did the right thing. I ran to the house, as fast as my legs would carry me.

But it was all over by the time they came back, by the time the doctor arrived. I stayed in the kitchen, with Mother; they wouldn’t let me go out there again, and when they finally returned it was much later. Too late. You see, Rose was gone. My beautiful sister was dead, and it was my fault. I should have stayed with her. Not without you, she’d said. And I let her down.

That was my first mistake, though I couldn’t be blamed for that, as everyone told me. I was only six. It was many, many years ago. But I know what I did was wrong. I left her when she needed me. I carried that mistake with me, maybe for too long. And when someone showed me a way out, a new life, I took it.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

Los Angeles, 2012

‘And … coming up next … Sophie Leigh’s diet secrets! How the British beauty stays slim, and the answer is … you won’t believe it! Chewing cardboard! I know, these stars are crazy, but that’s Hollywood for you. That’s all when we come back …’

IT’S A BEAUTIFUL May morning. We’re on the 101, on our way into Beverly Hills. I’m heading into my agent’s office and I feel like crap. I’m super late, too. I’m always late, but when your most recent picture had an opening weekend of $23 million it doesn’t matter. I could turn up at Artie’s mom’s funeral and demand to have a meeting and he’d clear the synagogue and thank me for coming.

I flip the TV off and chuck the remote across the car, out of temptation’s reach. There was a time when a ten-second trail like that would have sent me into a tailspin. They’re saying I chew cardboard? But it’s bullshit! People’ll believe it, and then they’ll … they’ll … Now I just shrug. You have to. I’ve never chewed cardboard in my life, unless you count my performance in that action movie. It’s a slow news day. Sometimes I think they stick a pin in a copy of People magazine to choose their next victim and then make something up.

When you’ve been famous for a while, you stop reacting to stuff like this. It just becomes part of life. Not your life, but the life you wake up to and realise you’re living. People filming you on a phone when you’re washing your hands in the Ladies’ room. Girls from school who you don’t remember selling your class photo to a tabloid. Being offered $5 million to sleep with a Saudi prince. Working with stars who won’t ever take their sunglasses off, ’cause they think you’re stealing their soul if you see their eyes. Sounds unbelievable, right? But there’s been some days when I almost know what they mean. I know why some of them go bat-shit crazy, join cults, wear fake pregnancy bellies, marry complete strangers. They’re only trying to distract themselves from how totally nuts being famous is. Because that’s what fame is actually about, these days. Not private jets, diamond tiaras, mansions and free clothes, handbags, shoes. Fame is actually about how you stay sane. How you don’t lose your mind.

I know I’m lucky. It could have been any one of hundreds of hopeful English girls from small towns with pushy mums who curled their hair and shoved them into audition rooms, but it was me, and I still don’t quite know why. All I know is, I love films, always have done, ever since I was little. Lights down, trailers on, credits rolling; I knew all the special idents the studios use to open a movie by the time I was eight. My favourite was always Columbia – the toga lady holding the glowing torch like the sun. And I know I’m good at what I do: I make movies for people to sit back and smile at on a Friday night with their best friend and their popcorn, watching while Sophie Leigh gets into another crazy situation. OK, it’s not Citizen Kane, but if it’s a bit of fun and you could stand to watch it again, is there anything wrong with that?

Lately I’ve been wondering though: maybe there is. Maybe it’s all wrong. The trouble is, I can’t work out how it all got like that. Or what I should do about it. In Hollywood, you’re either a success or you’re a failure. There’s no in-between.

The freeway is crowded, and as we slow down to turn off I look up and there I am, right by the Staples Center on a billboard the size of your house. I should be used to it but still, after six years at the top, it’s weird. Me, doing my poster smile: cute chipmunk cheeks, big dark eyes peeking out from under the heavy trademark bangs, just the right amount of cleavage so the guys notice and don’t mind seeing the film. I’m holding out a ringless hand, smiling at you. I’m cute and friendly.

Two years of dating. She’s thinking rocks.

No, not those ones, fellas …

SOPHIE LEIGH IS

THE GIRLFRIEND

May 2012

My phone rings, and I pick it up, gingerly, rubbing my eyes. ‘Hi, Tina,’ I say.

‘You’re OK?’ Tina asks anxiously. ‘Did the car come for you?’

‘Sure,’ I say.

‘The clothes were OK? Did you want anything else?’

Do I want anything else? The late-morning sun flashes in reflected rays through the windows; I jam my sunglasses on and sink lower against the leather seats, smiling at the memory of him asking the very same question, then taking my clothes off piece by piece, getting the camera out, and what we did afterwards. Oh, it’s probably insane of me, but … wow. He knows what he’s doing. I’m not some idiot who lets herself be filmed by a douche-bag who puts it on the Internet. This guy is a pro, in many many ways.

‘I’m good. Thanks for arranging it all.’

‘No problem.’ Tina is the most efficient assistant on the planet. She looks worried all the time, but I don’t think she actually cares where I was last night. ‘There’s a couple things. OK?’

‘Go ahead.’ I’m staring out the window, trying not to think about last night, smiling and biting my lip because … well, I’m exhausted, that kind of up-all-night skanky, hungry, and a little bit hungover exhausted. And I can’t stop smiling.

‘So …’ Tina’s voice goes into her list-recital monotone. ‘The People interview is tomorrow. They’ll come by the house. Ashley will arrive at eight a.m. Belle is doing your make-up frosty pink and mushroom – she says the vibe is Madonna eighties glamour meets environmental themes.’ Tina takes a breath. ‘DeShantay wants to drop off some more outfits for the Up! Kidz Challenge Awards. She has a dress from McQueen and she says to tell you you’re gonna love it. It’s cerise, has cap sleeves and it’s—’

‘I don’t want to sweat,’ I say. ‘Tell her no sleeves.’

‘DeShantay says it won’t be a problem.’

‘I’m not—’ I begin, then I stop, as I can hear myself sounding like a bit of a tool. ‘Never mind. That’s great. Anything else?’

‘Tommy’s coming over later this week to talk through endorsements. And he’s gotten Us Weekly to use some new shots of you doing yoga on the beach. And the shots of you grocery shopping are being run again, in In Touch. And TMZ want the ones of you getting the manicure, only they need to reshoot—’

‘OK, OK,’ I say, trying not to feel irritated, because it’s so fake, when you say it out loud, but it’s true, and everyone does it. You can so tell when someone doesn’t want their photo taken and when they do, and those ones of me pushing my trolley through the Malibu Country Mart wearing the new Marc Jacobs sandals and a Victoria Beckham shift, holding up some apples and laughing with a girlfriend, came out the same week as The Girlfriend and I’m telling you: it’s part of the reason that film has done so well. It’s all total bullshit though. The clothes were on loan, and the friend was Tina. My assistant. And I don’t go food shopping; I’ve got a housekeeper. Be honest. If you had someone to do all that for you, would you still go pushing a trolley round the supermarket? Exactly. Today stars have to look like normal, approachable people. Fifty years ago, it was the other way round. My favourite actress is Eve Noel; I’ve seen all her movies a million times, and A Girl Named Rose is my favourite film of all time, without a doubt. You didn’t have photos of Eve Noel in some 1950s Formica store buying her groceries in a dress Givenchy loaned her. Oh, no. She was a goddess, remote, beautiful, untouchable. I’m America’s English sweetheart. Pay $3.99 for a weekly magazine and you can see my nipples in a T-shirt doing the sun salute on Malibu beach.

Another thing: I starved myself for three days to fit into that fucking Victoria Beckham dress. That girl sure loves the skinny.

We’re off the highway, gliding down the wide boulevards of Beverly Hills, flanked on either side by vast mansions: old-looking French chateaux wedged right next to glass-and-chrome cubes next to English Gothic castles, Spanish haciendas, and the rest. My first trip here with my best friend Donna, both aged nineteen, driving round LA in a brown Honda Civic, these houses blew our minds – they looked like Toytown. It’s funny how things change. Now they seem normal. I know a couple of people who live in them, and I haven’t seen Donna in nearly seven years. Where is she now? Still living in Shamley, last time I Googled her.

We’re coming up to Wilshire and I need to check my make-up. ‘I’ll see you later,’ I tell Tina. ‘Thanks again.’

‘Oh – one more thing. I’m sorry, Sophie. Your mom called again.’ I stiffen instinctively. ‘She says you have to call her back.’ Tina clears her throat. ‘She says Deena’s coming to stay with you. Tonight.’

The compact mirror drops to the floor.

‘Deena? She can’t just— Tell her she can’t.’

Tina’s voice is apologetic. ‘Your mom said she has roaches and damp and it needs to be sprayed and … She’s got nowhere to go.’

‘I don’t care. Deena is not bloody staying. Why’s she getting Mum to phone up and do her dirty work for her anyway? No. No way.’

My head feels like it’s in a vice. It always aches when I don’t eat: I’m trying to lose ten pounds before The Bachelorette Party starts shooting.

‘Her cell is broken. That’s why. So – uh – OK.’ Tina’s tone conveys it all. She keeps me on the straight and narrow, I sometimes think. I’d be a Grade A egomaniac otherwise.

I clear my throat and growl. ‘Look. I’ll try and call Mum and put her off. Don’t worry about it. Listen though, if Deena turns up …’ Then I run out of steam. ‘Watch her. Make sure she doesn’t steal anything again.’

‘Sure, Sophie,’ says Tina, and I end the call with a sigh, trying not to frown. There are wrinkles at the corners of my eyes and lines between my eyebrows; I’ve noticed them lately. The Sophie Leigh on the poster doesn’t frown. She doesn’t have wrinkles. She’s twenty-eight, she’s happy all the time, and she knows how great her life is. That’s not true. I’m thirty, and I keep thinking I’m going to get found out.

CHAPTER TWO

‘SHE’S HERE! MAJOR star power incoming, people!’

Artie’s waiting for me as the elevator doors open, his arms open wide. ‘Sophie, Sophie, Sophie!’ The assistant on reception smiles, and someone whispers, ‘I loved your last movie,’ as I walk past, and Artie hugs me and kisses me on both cheeks. ‘Hola! She’s here, people!’

It’s all an act, and he knows I know it.

‘You look. Amazing,’ he says simply, and leads me through to his office suite, overlooking Wilshire Boulevard, the wide straight road lined with palm trees right along from Rodeo Drive where Julia Roberts went shopping in Pretty Woman. I like going into Artie’s office, seeing what’s going on, what’s new. And though it sounds stupid, I like being in places where normal people work. Not that anyone at World Artists’ Management is particularly normal, but I’m an actress. OK, I’ll never be Meryl Streep, but part of my job is to play girls who work in offices and you don’t get that realistic a view of the world living in the Hollywood Hills and having the kind of life where you have your own florist.

Once upon a time I used to be like everyone else. I’m beautiful, but so are many people. It’s like being left-handed or having freckles – it’s just a fact. Plus I freely admit that the facials, the clothes and the instantly recognisable bobbed hair do a lot of the work for me. Seven years ago you wouldn’t have looked at me twice on the street.

‘Sit down,’ Artie says, gesturing to a thin, angled leather couch in the centre of the room. There’s an armchair opposite, for him, and a box of Krispy Kremes on a glass table.

I stare at the doughnuts and my stomach rumbles. I’m so hungry. I’m always hungry but I haven’t eaten since yesterday lunchtime, unless you count the maki roll I had last night and the handful of popcorn – we watched a film before we went to bed. A film he’d made of us.

Tacky, I know. At the new memory of last night, I blush again, and my stomach rumbles with a sharp pain. Which is good. I hold onto that dragging, tightening feeling, the one you get when your stomach is crying out for food and you feel like you might faint. I hold it close, and smile brightly at Kerry, Artie’s assistant.

‘Can I get you something? Some coffee?’

‘That’d be great. No milk. And some water, please. Thanks so much, Kerry. Your top is so cute!’ I say, and she glows with pleasure.

‘Thanks, it’s from this totally—’

But Artie gestures that she should clear out, and Kerry’s mouth snaps shut. She retreats immediately, still smiling. Artie sits down, and stuffs a doughnut into his mouth. I watch him. I watch the crystals of sugar on his chin, on his fingers, watch his gullet move as he swallows.

When he pushes the box towards me with the tiniest of movements, I say nothing. I shake my head and give a regretful smile, though he and I both know, of course, I’ll never take a doughnut. It’s a test. I hate him just a little bit then.

‘So,’ he says, wiping his fingers and slapping his big meaty hands onto his black pants. ‘It’s great to see you, right? Everything’s good, isn’t it? It’s great!’

‘It’s great,’ I repeat.

He leans forward. ‘Honey. You’re being too British. The foreign numbers are in for The Girlfriend. We’ve already done forty million dollars – last week domestic gross was twelve million. That’s four weeks on! It’s killing everything else. It beat Will freakin’ Smith! You are back on top, baby. Back on top.’

‘Well, it’s the movie, not me,’ I say. This isn’t really true. The Bride and Groom, my breakthrough, was a really good film. Since then I think it’s been the law of diminishing returns, like Legally Blonde sequels. They’re not terrible, just not amazing. It’s not Tootsie: no one’s going to be studying the script of The Girlfriend in film school any time soon.

‘We’re on top of the world, OK? Enjoy it.’ His eyes linger on the doughnuts, and then he says, ‘So, you got a couple of weeks off now? Gonna read some scripts, take some meetings? Because we need to get thinking about your next project after The Bachelorette Party, don’t we? We’re excited about that, aren’t we? All good? You met up with Patrick yet?’

Artie put the deal together for The Bachelorette Party, the picture I’m due to start making in a few weeks. The male star, the director, the comedy-sidekick best friend, the scriptwriter and I are all agented by WAM. And Artie has got me a fantastic deal: I’m on a 20/20 – $20 million, 20 per cent of all revenues. If this film works, Artie will make a bomb.

‘No,’ I say. ‘It’s being fixed up.’

‘OK. Well, you’re gonna love Patrick, I promise you. He’s a straight-up guy. Brilliant comedian. I think you two’ll really get along.’

Patrick Drew is my co-star. He is a surfer dude with tatts who is always being photographed stoned or punching paparazzi. Last month they got him throwing up out of the side of a car, speeding along Santa Monica Boulevard. He’s extremely hot, but dumb as a plank. Apparently, we’re really lucky to get him because, you know, he’s authentic.

Artie reaches forward for another doughnut. His large meaty fingers hover over the cardboard tray, touching the smooth, shiny caramel frosting of one, the plump slick of custard on the other. I close my eyes for a second, thinking about how the sweet, fluffy cream inside would taste on my tongue. No. No. You fat bitch, no.

‘How about George?’ Artie says heavily, and when I open my eyes his mouth is full and he’s brushing sugar off his trim beard. ‘You guys met last month, yes?’

‘Yes. He’s great.’

‘George is a fucking great director.’ Artie nods. ‘The guy’s a genius. You’re lucky.’

‘I know it. He is a genius. I’m very lucky.’ I’m parroting it back to him.

Artie gives me a curious look. ‘I’m glad you two are getting along. Tell me something—’

Kerry comes in with the coffee and the water. Artie nods at her then shakes his head, swivelling on his chair.

‘Forget it.’ He rubs his hands. ‘What comes next, after you wrap on The Bachelorette Party. This is what we need to think about. The new Sophie Leigh Project, Fall 2013.’

Now’s my moment. My palms are a bit sweaty. I rub them together. ‘Actually, I’ve been wanting to talk to you about that.’

‘Great!’ Artie smiles happily.

I take a sip of the water ‘Just … run some things past you.’ I don’t know why I feel nervous. It’s crazy. I’m the A-Lister – a film with me in will always be a tent pole, something for the studios to prop up their profits with while they try out other, smaller, more interesting projects. ‘I’ve had some ideas … been thinking about them for a while. I – wanted to find the right time to pitch them to you.’

Artie frowns. ‘You shoulda told me. I’d have come over. Twenty-four/seven, Sophie, I’m always here. You’re my number one priority.’

‘It’s OK, I’ve been crazy with promotional stuff,’ I say. ‘I only – I want us to think carefully about what we do next. I kind of want to move along a bit. Not make the same old film again.’

Artie nods violently. ‘Me too, me too,’ he says. ‘Man, this is great, you’re totally right! I totally agree.’

‘Oh, good!’

‘Sophie. You’re a really talented actress. We have to make sure we exploit that. Let me show you something.’ He’s still nodding. Then he stands up, strides to the other side of the huge office, picks up a pile of paper.

My gaze drifts out the window. Downtown Beverly Hills gleams through the glass wall. It’s a beautiful day. Of course it is. The purple-blue jacaranda trees are out all over LA; they stretch in a line down towards West Hollywood. It’s spring. Not like spring at home in the UK though, where everything’s lush and green and hopeful. In northern California the wild flowers litter the canyons and mountains along Route 101, and the fog clears earlier in the mornings and the surf frills the waves, but in LA spring is like any other season: more sunshine. It’s the only time I miss home. I was never a country girl, but you couldn’t live in Gloucestershire and not love the bulbs coming up, the wet black earth, the freshly minted green everywhere. Sometimes I wish—

A loud thud recalls me to my senses as Artie throws a script on the table in front of me. ‘This,’ he says. ‘This will blow your mind.’

I look down at the title page. ‘Love Me, Love My Pooch’, I read.

‘Yes!’ Artie’s rubbing his hands. ‘It’s getting a lot of heat. Cameron’s interested, but she’s way too old. Universal want it for Reese but I heard she passed already. And some people say Carey Mulligan is super keen. So we need to move fast. Do you want to read it tonight?’

I’m still staring at the script. ‘Carey Mulligan wants to star in Love Me, Love My Pooch?’

Artie nods, looking amazed. ‘Sure, honey. Why not? You think – oh, wait, do you think it’s, ah, kinda silly? The title?’

‘A bit,’ I admit, relieved. ‘It’s—’

‘No problem!’ He waves his hands. ‘Listen. We can change that. The important thing is the material. And the material is fan. Tastic.’

‘What’s it about?’

‘I heard it’s Legally Blonde meets Marley and Me. Schlubby guy meets hot girl, hot girl not interested, schlubby guy uses dog called Pooch to get hot girl. Girl falls for schlubby guy.’ He laughs. ‘Cute, huh? It’s so cute!’

I hear myself say, ‘Yeah! Sounds good.’ Then I correct myself. ‘What I mean, Artie, is – sure it’ll be great, but I don’t know.’ I take a breath. ‘I’d like to do a movie that’s – uh. Maybe not about some girl hanging out for a boyfriend and being ditzy. Something a bit more interesting.’

Artie nods enthusiastically. He brushes sugar off the front of his black silk shirt. ‘Great. Sure. I’m with you. Let’s talk about it. I can see you want a change. You’re not just a beautiful face. You’ve got so much talent.’

‘Well … thanks.’ I nod politely; I’ve learned to accept compliments over the years. Not that everyone agrees with him. The critics are … hmm, how shall I put this? Oh, yeah, VILE about my films; the more money I make the ruder they are. ‘Sophie Leigh’s Sweetener Overload,’ the LA Times called my last movie.

‘Listen, I don’t want to play Chekhov or anything. I’m not one of those annoying actors who tries to prove themselves on Broadway.’ I can hear my voice speeding up. ‘It’s that I don’t always want to be playing someone who’s a dippy girlie girl who gets drunk after one cocktail, who’s obsessed with weddings and babies and has a mom and dad with funny one-liners who live in the suburbs.’

There’s a pause, as Artie tries to unpick what I’m saying. ‘I guess you’re right.’ The smile has faded from his eyes and he’s silent for a moment, tapping one foot against the coffee table. ‘We don’t want to get into a Defence: Reload situation,’ he continues, suddenly. ‘You’re back on top. We shouldn’t jeopardise that, Sophie, that’s totally true.’

‘No way,’ I say warmly. Though I hadn’t said anything of the sort, he’s right. ‘God, that was terrible.’

‘Listen.’ He grabs my hands. ‘You were great in it! Astonishing! It’s just America’s not ready for you to do martial arts action.’ He shrugs. ‘Or hipster mumbly independent shit. You’re with me now, OK? I am never gonna let you make the same mistake.’

‘Sure.’ Artie’s right, as always. Anna was my old UK agent back from South Street People, the teenage soap that I had my first big role in. I left her after first Goodnight LA, the art-housey independent film I’d always wanted to make, disappeared without trace and then Defence: Reload totally bombed. Two flops in a row. Biiiiiig mistake. Huge. As they say. I’m not made to wear leather and do high-kicks. The film was horrible and Anna was useless about it – everything seemed to take her by surprise and she’d flap and cry down the phone. It was time for a change. I went with Artie, and he put me in Wedding of the Year, and it spent three weeks at number one and was the fifth-biggest grossing picture of 2009. Anna understood I had to move. It’s all part of the game – we’re still friends. (Translation: I sent her a gift basket. We’re not friends.)

‘I’m not talking about doing another Defence: Reload,’ I say. ‘But … well, I don’t always have to be the daffy girl who loses her engagement ring, do I? Look at that pile. There has to be something in there.’

Artie gets up. ‘You don’t want to see everything, trust me. Here’s the highlights.’

He flicks the list over to me.

Bridezilla. Boy Meets Girl. Bride Wars 2. Two Brides One Groom. I glance down the list, the same words all leaping out and blurring into one huge inkjet mush of confetti. I turn the page. ‘This is the rest of the scripts I’m getting sent?’

‘Yeah, but you don’t need to worry about that. These are not projects to take seriously.’

I scan the second and third pages. Pat Me Down. She’s So Hot Right Now. From Russia with Lust. ‘What’s My Second-Best Bed?’ I say wearily.

Artie takes the piece of paper off me and looks at the list. ‘No idea,’ he says. He gets up and goes over to his glass desk, taps something into his computer. ‘Hold on. Oh, yeah. It’s some time-slip comedy. They sent it to you because … there was some note with it. I remember reading it but I can’t remember it. I think it was because you can do a British accent.’

‘Well – yes,’ I say. ‘They’re right there. What is it?’

‘Second-Best Bed …’ His finger strokes the mouse. ‘Second-Best – oh, yeah, here it is. She’s a guide at Anne Hathaway’s cottage and she dreams Shakespeare comes and visits her.’ Artie shakes his head, then turns to the shelf behind him, picking a script out of a pile. ‘Who’d wanna guide people round Anne Hathaway’s cottage? Why’s Anne freaking Hathaway living in a cottage anyways? She just got a place in TriBeCa. I don’t understand, that’s crazy.’

‘Anne Hathaway was Shakespeare’s wife,’ I say. ‘That’s who they mean. Her house was outside Stratford-upon-Avon.’ I’ve been to Anne Hathaway’s cottage about three times. It was a short coach drive from my school. Closer than the nearest Roman fort or working farm, so our crappy school used to take us there every year – it was almost a joke. I remember one year Darren Weller escaped from the group and ran into the forest. They had to call the police. Darren Weller’s mum came to meet the coach. She screamed at Miss Shaw, the English teacher, like it was her fault Darren Weller was a nutcase. I can picture that day really clearly. Donna and I went to McDonald’s in Stratford and drank milkshakes – simply walked off while the others were going round his house or something. It’s the naughtiest thing I’ve ever done.

It’s funny – I never thought Donna and I would lose touch. We stopped hanging out so much when I moved to London for South Street People, then she had a baby. She wasn’t best pleased when I told her I was off to Hollywood. I don’t think she ever really believed I wanted to be an actress. She thought it was all stupid, that Mum was pushing me into it.

‘OK, OK.’ Artie isn’t interested. ‘Take them, read them through if you want. But will you do me a favour?’ He puts his hand on his chest and looks intently at me. ‘Will you read Love Me, Love My Pooch for me? As a personal favour? If you hate it, no problem. Of course!’ He laughs. ‘But I want to see what you think. They’re offering pretty big bucks … I have a feeling about this one. I think it could be your moment. Take you Sandy–Jen big. That’s the dream, OK? And I’m working on it for you.’ He takes his hand off his chest, and gives me the script, solemnly. ‘Now, tell me what picture you’d like to make. Let’s hear it. Let’s make it!’ He claps his hands.

I’m still clutching the pile of scripts, with Love Me, Love My Stupid Pooch on the top. I clear my throat, nervously.

‘I want to … This is going to sound stupid, OK? So bear with me. You know I moved house last year?’

‘Sure do, honey. I found you the contractors, didn’t I?’

‘Of course.’ Artie knows everyone useful in this town. ‘You know why I bought that house?’

‘This is easy. Because you needed a fuck-off huge place means you can tell the world you’re a big star. “Look at me! Screw you!”’ Artie chuckles.

‘Well, sure,’ I say, though actually I don’t care about that stuff that much the way some people do. I’ve got a lot of money, I give some of it away and I take care of the rest, I don’t need to go nuts and start buying yachts and private islands. This was the place I always wanted. It’s a beautiful thirties house, long, low, L-shaped, high up in the hills, kind of English meets Mediterranean, simple and well built. Blue shutters, jasmine crawling over the walls, Art Deco French doors leading out to a scallop-shaped pool.

I love it, but it has a special connection that means I love it even more.

‘I bought the house because it belonged to Eve Noel. She lived there after her marriage.’

Artie’s lying back against the couch. He scrunches up his face. ‘Who? The … the movie star? The crazy one?’

‘She wasn’t crazy.’

Artie scratches his stomach. ‘Well, she disappeared. She was huge, then she vanished. I heard she was crazy. Or dead. Didn’t she die?’

‘She disappeared,’ I say. ‘She’s still alive. I mean, she must be somewhere. But no one knows where. She made those seven amazing films, she was the biggest star in the world for five years or so, and then she vanished.’

‘OK, so what?’ Artie puts his hands behind his head.

‘I want to make a film about her.’

From my bag I pull out a battered copy of Eve Noel and the Myth of Hollywood, the frustratingly slim biography of her that ends in 1961. I must have read it about twenty times. ‘So … it’d be a film about where she came from, about her starting out in Hollywood, what happened to her, why she left.’

‘I never knew you were into Eve Noel. Old movies.’ Artie makes it sound like I’ve told him I love anal porn.

‘Sure,’ I say. ‘My whole childhood was spent on the sofa watching videos. It’s a wonder I don’t have rickets – I never saw the sun.’

Artie grunts. He doesn’t much like funny women. ‘So why the big obsession with her?’

‘She’s the best. The last real Hollywood star. And she … She grew up near me, a little village near Gloucester?’ I can hear the edge of the West Country accent creep into my voice, and I stutter to correct it. ‘It’s crazy, no one knows what happened to her, why she left LA.’

The first time I saw A Girl Named Rose, I was ten. I remember we had a new three-piece suite. It was squeaky, because Mum didn’t want to take off the plastic covers in case it spoiled. I was ill with flu that knocked me out for a week and I lay on the sofa under an old blanket and watched A Girl Named Rose, and it changed my life. I never thought about being an actress before then, even though Mum had been one, or tried to, before I was born, but after I saw that film it was all I wanted to do. Not the kind Mum wanted me to be, with patent-leather shoes and bunches, a cute smile, parroting lines to TV directors, but the kind that did what Eve Noel did. I’d sit on the sofa while Mum talked on the phone or had her friends over, and Dad worked in the garage – first the one garage, then two, then five, so we could afford holidays in Majorca, a new car for Mum, a bigger house, drama school for me. The world would go on around me and I’d be there, watching Mary Poppins and Breakfast at Tiffany’s, anything with Elizabeth Taylor, all the old musicals, Some Like It Hot … you name it, but always coming back to Eve Noel, A Girl Named Rose, Helen of Troy, The Boy Next Door. I even cut out pictures of my favourite films and made a montage in my room: Julie Andrews running across the fields; Vivien Leigh standing outside Tara; Audrey Hepburn whizzing through Rome with Gregory Peck; Eve Noel walking down the road smiling, hands in the pockets of her flared skirt.

Everyone else at school thought I was weird. It was weird, probably. But Eve Noel and that film opened a world up for me. It seemed magical. It isn’t, any more, and I should know. Back then it was all about glamour and artifice, these gods and goddesses deigning to appear on a screen for us. Whereas I know what it’s like now. It’s a business, less profitable than online poker, but a profitable business still, until the Internet kills it totally dead.

Mum and I used to drive past Eve Noel’s old house. It’s in ruins now. It’s funny – everyone knows that’s where a film star grew up. But no one knows the film star any more, or even where she is now. Her last picture was Triumph and Tragedy, in 1961, and it was a big flop. There’s a picture of her at the Oscars, the year she didn’t win and her husband did. She’s smiling, so lovely, but she doesn’t look right. Her eyes are odd, I can’t describe it. And then – nothing.

I try and explain all this to Artie. He nods enthusiastically. ‘Give me the pitch then,’ he says.

‘The pitch?’

He’s grinning. ‘Come on, Sophie. You know it’s you, but you’re gonna have to get some big guys to put big money up if you want this thing made. Give me the one-line pitch.’

‘Oh …’ I clear my throat. ‘Kind of … A Star is Born meets … um … Rebecca? Because the house burns down. I suppose maybe it’s more The Player set in the fifties meets A Star is Born, or—’

‘Boorrring!!’ Artie buzzes. My head snaps up – I’m astonished.

‘Listen,’ he says. ‘You are my number one client. You are so important to me. This could be amazing. I’m talking Oscar-amazing. But it could be career suicide. Again. And you can’t afford that. Again.’

He stands up again and pats his stomach. ‘I’m a pig. I’m a pig! Listen to me, sweetheart. Go home. Think up a great pitch. We have to get this thing made.’

‘Really?’ I stand up, stumbling slightly.

‘Really. But you’re totally right. If we can’t do it properly we should forget all about it.’

‘That’s not—’

‘And you’ll read the dog script? For me? Think about who’d be good, who you’d like to work with?’ I must have nodded, because he gives a big smile. ‘Thank you so much. Take the other scripts. Read them. I wanna know what you think of them all. I’m interested in your opinion. Sophie Leigh Brand Expansion. We’re big, we need to go bigger, and you’re the one who’s gonna lead us there. Capisce?’

‘Thanks, Artie,’ I say, aware that something is slipping from my grasp but unsure of how to take it back. ‘But also the Eve Noel project, let’s think—’

‘Sure, sure!’ He pats me on the back and squeezes my shoulder. ‘I think with the right project and a good writer we could have something wonderful. And listen, I spoke to Tommy, did he tell you?’ I shake my head. Tommy’s my manager, and he rings Artie roughly ten times a day with ideas, most of which Artie rejects. ‘It’s fantastic news!’

‘What?’

‘He tested the line we discussed for the Up! Kidz Challenge Awards on a focus group and it came back great. So that’s what you’re saying. OK? Wanna give it a try, for old times’ sake?’

I smile obligingly, hold up my bare left hand, then scream, ‘I LOST MY RING!!!’

This is the line I’m famous for, from The Bride and Groom. It’s a cute film actually, about a wedding from the girl’s point of view: bitchy bridesmaids, rows with parents – and from the guy’s point of view: problems at work, a bachelor party that ends in disaster. The bride, Jenny, loses her ring halfway through in a cake shop, and that’s what she screams. I don’t say it often, because I don’t want to have a catchphrase. Tommy would sell dolls that scream ‘I LOST MY RING’ and T-shirts by the dozen if I let him. I don’t let him.

‘Wonderful. Just wonderful.’ Artie’s clutching his heart. I push my sunglasses back down over my eyes.

‘It’s good to see you,’ I say, hugging him. ‘We’ll talk soon. When are the awards?’

‘Two weeks. Ashley will brief you. So you’re OK? You know you’re going with Patrick, yes?’

I hesitate. ‘Well, and George,’ I say. ‘A bonding night out before we start shooting.’

‘George? OK.’

I match him stare for stare and as I look at him I realise he knows.

‘George is a great director.’ For once Artie’s not smiling. His tanned face droops, like a hound dog. His beady eyes rake over me.

‘I know he is,’ I say slowly.

‘That’s all.’ He turns away. ‘That’s all I’m gonna say. OK?’

I can imagine what’s going on in his mind. If she’s banging George, they’ll be making trouble on set. Patrick Drew’s gonna get difficult about his close-ups as it’ll all be on her. George’ll dump her halfway through and start fucking someone else and she’ll go schizoid. This is a disaster.

I know it’s nothing serious, me and George. He’s A-list, so am I; we won’t squeal on each other. He’s way older than I am, he’s been around. Plus I don’t need a relationship at the moment, neither does he. If we screw each other once a week, what’s the harm?

Artie chews something at the back of his mouth, rapidly, for a few seconds, then claps his hands. ‘OK, we’ll regroup afterwards about your Eve Noel idea. I like it, you know. If not for you then someone. Maybe you’re right! Could be big …’ He pauses. ‘Hey, you should be a producer.’

He laughs, and I laugh, then I wonder why I’m laughing. Me, in a suit, putting the finance on a movie together, all of that. Then I think … no. That’s not for me, I couldn’t do that. I’m too used to being the star – it’s true isn’t it?

‘Read the scripts, think it over,’ he says, as I leave the room. ‘Then we’ll talk.’

CHAPTER THREE

AS I EXIT the building, I’m still thinking about Darren Weller and the day we went to Stratford, me and Donna escaping to McDonald’s. I’m smiling at the randomness of this memory, walking through the glass lobby of WAM, clutching this bunch of scripts, and suddenly—

‘Ow!’ Someone’s bumped into me. ‘Fuck,’ I say, rubbing my boob awkwardly and trying to hold onto the scripts, because she got me with her elbow and it is painful.

This girl grips my arm. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she says, her eyes huge. ‘Oh, my gosh, that was totally my fault. Are you OK—?’ She looks at me and laughs. ‘Oh, no! That’s so weird. Sophie! Hi! I didn’t recognise you with your shades on.’

I’m trying not to rub my boob in public. I can see T.J. waiting by the car right outside. ‘Hi there,’ I smile. ‘Have a great day!’

‘You don’t remember me, do you?’

I stare at her. Who the hell is she? ‘No, I’m sorry,’ I say, beaming my big megawatt smile and going into crazy-person exit-strategy mode. ‘But, it’s great to meet you, so—’ She’s still grinning, although she looks nervous, and something about her eyes, her smile, I don’t know, it’s familiar. ‘Oh, my God, of course,’ I say impulsively. I push my sunglasses up onto my head. ‘It’s …’

I search my memory, but it’s blank. The weird thing is, she looks like me.

‘Sara?’ she says hesitantly. ‘Sara Cain. From Jimmy Samba’s.’ She’s still smiling. ‘It’s been so long. It’s really fine.’

I stare at her, and the memory leads me back, illuminating the way, as scenes light up in my mind from that messy, golden summer.

‘Sara Cain,’ I say. ‘Oh, my gosh.’

Back in 2004 I starred in a sweet British romcom, I Do I Do, during a break in South Street People’s shooting schedule. It did really well, better than we all expected, and LA casting agents started asking to see me, so I went out to Hollywood again the following summer. That was when Donna and I kind of fell out, actually; she told me it was a big mistake and I was in over my head.

She was wrong, as it turns out. It was a great time. I was young, didn’t have anything to lose, and I thought it was pretty crazy that I was there anyway, to be honest. Jimmy Samba’s was the frozen-yoghurt place on Venice Beach where my roommate Maritza worked and we all practically lived there: a whole gang of us, actors, writers, models, musicians, all waiting for that big break.

‘Your twin, remember?’ I stare at her intently. She gives a small, self-conscious giggle.

‘Wow,’ I say. ‘The twins. Sara, I’m so sorry, of course I remember you.’

The thing about her was, we had a few auditions together, and every time people always commented on how similar we looked. She had a couple of pilots, and the last time I saw her it looked like things might be about to happen for her.

The sight of her is like hearing ‘Hollaback Girl’ – that was my song of that summer. Takes you totally back there to a time that I rarely think about now. It’s gone and that’s weird, because we were friends. Her dad was a plastic surgeon, I remember that now, an old guy who’d done all the stars; I loved hearing her stories about him. She even came up to the rental house in Los Feliz, her and some of the gang, after I moved out of Venice. But it was an uncomfortable evening. Sara especially was weird. And even though I called her and a few others a couple of times afterwards, no one returned my calls. Turns out we weren’t all friends, just people in similar situations, and I didn’t belong in that gang, the clique of hopefuls. I’d passed onto the next stage, and they didn’t want to know me any more.

Now I try to look friendly. ‘That’s so cool, bumping into you here. How’s it going? Who are you here to see?’

She doesn’t understand and then smiles. ‘Oh. I’m not acting these days.’ My face is blank. She smiles again, a little tightly. ‘I – work here? I’m Lynn’s assistant? She’s in the same department as Artie.’

‘I know Lynn,’ I say. ‘OK, so …’ I trail off, embarrassed.

‘It’s fine,’ she says, nodding so her perky ponytail bounces behind her. ‘It’s totally fine. Guess some of us have it and some of us don’t. I don’t miss the constant rejection, for sure. That time they told me no when I walked in the room, you remember that?’

I screw up my face. ‘Oh … oh, yeah, I remember. What was it for?’

‘It was The Bride and Groom, Sophie.’ She grins. ‘You should remember, we were totally hungover from being up all night drinking Bryan’s tequila?’

‘Oh, my God,’ I say, shifting my bag onto my other shoulder. ‘That night.’

‘Some of us get the right haircuts at the right time, you mean!’ Sara smiles, and says suddenly, ‘That was a totally insane evening, wasn’t it? You getting that bob, like … who was it? Eve Noel?’ She looks at my hair. ‘Still rocking it, right? You always said those bangs got you the part – maybe that’s what it took!’ She stops, and then looks alarmed. ‘Sorry,’ she says, flushing. ‘I mean, of course … you’re so good as well, you totally deserve it!’

‘No way. I was probably drunk,’ I said. ‘I’d never have got that bob if I hadn’t been totally bombed. I owe Bryan … it was Bryan, wasn’t it?’

She nods. ‘It was.’

My memory is so shit, it’s terrible. Maybe the tequila drowned my brain cells, because they were kind of crazy times. We behaved pretty badly, we didn’t have anything to lose. I was still seeing Dave, my boyfriend back in London who I met on South Street People, but I knew he was cheating on me by then. (Turns out he was cheating on me about 80 per cent of the time we were together anyway.) It’s the only slutty period of my life; maybe everyone has to have a summer like that. I’d always worked so hard and all of a sudden it was so easy. America was easy. Sunshine, friendly people, and I was young. I lived for the ocean, the cafe, the bars and the crowd I hung out with.

I loved acting, but I never thought I’d make it, to be honest. I knew I wasn’t as talented as someone like Sara, knew I wasn’t trained. I didn’t know anything about stagecraft or method; I turned up and said the lines the best way I could. Still do, I think. I’d already got further with my career than I’d ever expected to without Mum by my side all the time, and I suppose I thought I’d ride it for as long as I was allowed to. They’d find me out and I’d be sent home and so for the time being, I reasoned, I should hang loose and enjoy myself – and for once, I really, really did.

I stroke my forehead and fringe, trying to remember. ‘Bryan. He was hot, wasn’t he? Kind of Ashton Kutcher-y.’

She smiles. ‘That’s him.’

‘I think I slept with him,’ I muse.

‘Yeah, I know,’ she says, then she adds, ‘You know, I went out with him for a while. Maybe we are twins!’

There’s an awkward pause. Sara clears her throat, and stares at me after a moment. ‘Sorry,’ she says. ‘I’m being weird. But it’s really good to see you, that’s all. I never returned your calls. I suppose I was jealous. Brings back those days and it’s crazy, remembering how it used to be, I guess.’

‘You were really good,’ I say, changing the subject. She looks uncomfortable, but I press her. ‘Have you totally left it behind? That’s a real shame.’

Sara knits her fingers together. ‘Yeah. At my last audition, this guy, the director I think it was, stared at me and said, “This girl’s just an uglier Sophie Leigh. Next, please.”’ She’s smiling as she says this, but there’s an awful expression in her eyes. ‘That’s what made me give it up.’

‘That … that sucks, Sara.’ We’re silent. I sling my bag over my shoulder again and as the silence stretches on, and Sara says nothing, blurt, ‘So, Bryan! What’s he doing now?’

‘Bryan moved to New York. He has his own salon now – he’s doing really well.’ She recovers her smile again. ‘Hey, I’m super happy for him. And for you! You totally deserve your success, Sophie! It’s not only about the bob, so don’t believe people who tell you it is!’

‘Uh – thanks.’ Maybe it’s time to go. ‘Great to see you, Sara.’ I wave to T.J., my driver.

Sara calls after me, ‘You look so great, Sophie. Sorry again!’

I stride out, smiling at another WAM minion who glows when she spots me and at the doorman as I exit the building, momentarily catching the wall of fierce afternoon heat.

I climb into the car, sinking into my seat. T.J. has got me a diet root beer and some carrot and celery sticks, and there’s even a packet of crisps (which I’ll never eat, of course), all nicely laid out in the back. Chips, I should say. I’m mostly American these days, but some things never feel right. Chips are the chips you have with fish and burgers.

‘Mulberry sent you over some new stuff to pick out. Tina was unpacking it when I left and she told me to tell you,’ T.J. says. He pulls the limo away from the kerb.

‘Get Tanisha to come over.’ Tanisha is T.J.’s daughter.

‘I’ll call her. That’s kind of you. She did well on her test yesterday, Sophie, I’m real pleased with her.’

A thought occurs to me. ‘Did Deena arrive yet?’

‘I don’t know,’ T.J. says firmly. ‘She wasn’t there when I left.’ He switches topic. ‘So how’s your day going?’

I have to think for a moment. ‘Not sure.’ Now we’re gliding away from WAM, I recall what I wanted to say to Artie, and what in my hungover state I actually said. I said I would read that stupid script. I didn’t really get to talk about Eve Noel, the film I want to make one day, the mystery about her that I still don’t understand. Not because it’s complicated, because that’s obvious. But because she was new in town once like I was, and it must have started out OK for her. And I don’t know what happened to her, no one seems to know or care. I’m on every billboard in town but she was the last great film star, to my mind. Hollywood is about extremes, as someone once said. You’re either a success or a failure, there’s no in-between.

We’re turning into Sunset, right by the Beverly Hills Hotel, and I glance over at the white italic scrawl, the palm trees that reach up to the endless blue. I pull my sunglasses on and lie back against the soft leather. For a few minutes I can be still. Don’t have to worry about that wrinkle on my forehead, that bulge in my stomach, that crappy script, that feeling all the time that someone else, someone better, should be living my life, not me.

the avocado tree

Los Angeles, 1956

‘NOW, MY DEAR,’ Mrs Featherstone whispered to me as we entered the crowded room. ‘Don’t forget. Call everyone Mr So-and-So and be simply fascinated, no matter what they say. You understand?’

‘Yes, Mrs Featherstone,’ I answered obediently.

She put her hand on my back and smiled mechanically. ‘And remember, what are you called?’

‘Eve Noel.’

‘That’s it. Good girl. Your name’s Noel now. Don’t forget.’

Her thumb dug into my shoulder blade. I could feel the side of her ring pushing into my flesh and involuntarily I stepped away, then smiled politely, looking around the room.

It was a beautiful old mansion house in Beverly Hills; at least it looked old, though they told me afterwards it had only been finished last year. At the grand piano a vaguely familiar man sat playing ‘All the Things You Are’ and my skin prickled with pleasure: I loved that song. I had danced to it only two weeks ago, on our clapped-out gramophone in Hampstead. Already it seemed like a lifetime ago.

Mr Featherstone was at the bar, shaking hands, clapping shoulders. When he saw his wife, he nodded mechanically, excused himself and came over.

‘Hey,’ he said, nodding at his wife, ignoring me. ‘OK.’ He turned to the three men standing in a knot beside us, and grasped the hand of the first one.

‘Hey, fellas, I want you to meet someone. This is Eve Noel. She just arrived from London, England. She’s our new star.’ His arm was around my waist, his fingers pressed tightly against the black velvet. I wanted to shrink away.

Each man balanced his cigarette in the cut-crystal ashtray, then turned to shake my hand. I had no idea who they were. The third, younger, man narrowed his eyes, and turned away towards the piano player to ask him something. The first man smiled, kindly I thought. ‘When did you get here, Eve?’

‘Two weeks ago,’ I said.

‘Where are you staying?’ He smoothed his thinning hair across his shiny pate, an automatic gesture.

‘She’s at the Beverly Hills Hotel at the moment, and Rita is chaperoning her where necessary,’ Mr Featherstone said before I could speak. He cleared his throat importantly. ‘Eve is our Helen of Troy, we’re announcing it next week.’

‘Good for you,’ said the second man. ‘Louis, you dark horse. You swore you’d got Taylor.’

‘We went a different way. We needed someone … fresh, you know. Elizabeth’s a liability.’ His hand tightened on my waist and he smiled.

‘That’s great, that’s great,’ said the first man. ‘So – you got what you wanted from RKO, Louis? I heard they wouldn’t give you the budget.’

He and the second man smirked at each other. ‘Oh,’ said Mr Featherstone. He flashed them a quick, automatic smile. ‘Hey, we all make mistakes, don’t we.’ His voice faltered. ‘But they’re coming around. We’ll start principal photography in a couple of weeks – we don’t need the money right now. It’s only that – well, fellas, this thing is going to be huge, and I’d like a little extra, you know? I’ve been thinking, a big studio might like to share some costs. I assure you, they’d get more than their share back. MGM and David O. Selznick, ring any bells?’ He winked at the first man, as though trying to make him complicit in something. ‘But let’s not talk business in front of Miss Noel.’

‘Of course,’ said the second man. He was short and greying where the first man was short and fat with black hair; they looked similar, and it occurred to me suddenly they must be brothers. ‘How do you find LA, Miss Noel?’

‘Oh,’ I said. I moved away from Mr Featherstone’s hand. ‘I think it’s wonderful.’

‘Wonderful, eh?’

‘Oh, yes, wonderful.’ I could hear myself: I sounded dull and stupid.

He laughed. ‘How so?’

‘Oh, the …’ I couldn’t think of how to explain it. ‘The sunshine and the palm trees, and the people are so friendly. And there’s as much butter as you like in the mornings.’

He and his companions laughed; so did Mr and Mrs Featherstone, a second or two later.

‘I’m from London,’ I said.

‘No,’ the first man said, faux-incredulous. ‘I would never have guessed.’

I could feel myself blushing. ‘Well, it’s only – we had rationing until really quite recently. It’s wonderful to be able to eat what you want.’

‘Now, dear!’ Mrs Featherstone said. ‘We don’t want you talking about food all night to Joe and Lenny, do we! They’ll worry you’re going to ruin that beautiful figure of yours.’ Again the thumb, jabbing into my back.

‘Oh, no!’ I tried to smile. As with everything else here I was constantly trying to work out what the rules were; I always felt I was saying the wrong thing.

‘I’m sure that would never happen.’ I jumped. The third man, who’d not yet spoken, had turned back from the piano and was eyeing me up and down, like a woman scanning a mannequin in a shop window. He smiled, but it was almost as though he were laughing. ‘You look as if you were born to be a star,’ he said.

It was all so ridiculous, in a sense. Me, Eve Sallis, a country doctor’s daughter, who this time two months ago was a mousy drama student in London, sharing a tiny flat in Hampstead, worried about nothing so much as whether I could afford another cup of coffee at Bar Italia and what lines I had to learn for the next day’s class: there I was, at a film producer’s house in Hollywood, dressed in couture with a new name and a part in what Mr Featherstone kept referring to as ‘The Biggest Picture You Will Ever See’. Tonight a beautician had curled my short black hair and caked on mascara and eyeliner, and I’d stepped into a black velvet Dior dress and clipped on a diamond brooch, and a limousine with a driver wearing a peaked hat had driven me here, though it was a 300-yard walk away and it felt so silly, when I could have trotted down the road. But no, everything was about appearance here. If people were to believe I was a star then I had to behave like a star. Mr Featherstone had spotted me in London. He had spent a great deal of money bringing me over and I had to act the part. It was a part, talking to these old men, exactly like Helen of Troy. And I wanted to play her, more than anything.

‘Well, I’m Joseph Baxter,’ said the first man, leaning forward to take my hand again. He really was quite fat, I noticed now. ‘This is my brother Lenny, and this interesting specimen of humanity is Don Matthews. He’s a writer.’ He tapped the side of his nose. ‘First rule of Hollywood, Miss Noel. Don’t bother about the writers. They’re worthless.’

The third man, Don, nodded at me, and I blushed. ‘Hey there,’ he said. He shook my hand. ‘Well, let me welcome you to Hollywood. You’re just in time for the funeral.’

‘Whose funeral?’ I asked.

They all gave a sniggering, indulgent laugh as a waiter came by with a tray. I took a drink, desperate for some alcohol.

Don smiled. ‘Miss Noel, I’m referring to the death of the motion picture industry. You’ve heard of a little thing called television, even in Merrie Olde England, I assume?’

I didn’t like the way he sounded as though he were poking fun, and the others didn’t seem to notice. Nettled, I said, ‘The Queen’s Coronation was televised, over four years ago, Mr Matthews. Most people I know have a television, actually.’

I sounded like a prig, like a silly schoolgirl. The three older men laughed again, and Mr Featherstone raised his eyebrows at the two brothers, as if to say, ‘Look fellas, I told you so.’ But Don merely nodded. ‘Well, that’s told me. I guess someone should tell Louis then, before he starts making The Biggest Picture You Will Ever See.’

Mr Featherstone looked furious; his red nostrils flared and his moustache bristled, actually bristled. I’d discovered in my whirlwind dealings with him that he had no love for a joke. I knew what Mr Matthews was talking about, though. Every film made these days seemed to be an epic, a biblical legend, a classical myth, a story with huge spectacle, as if Hollywood in its death throes were trying to say, ‘Look at us! We do it better than the television can!’

‘We’ll come by and meet with you properly,’ Mr Featherstone told Joe and his brother. ‘I’d like for you to get to know Eve. I think she’s very special.’

‘We should … arrange that.’ Joe Baxter was looking me up and down once more. ‘Miss Noel, I agree with Louis, for once. It’s a pleasure to meet you.’ He took my hand. His was large, soft like a baby’s, and slightly clammy. He breathed through his mouth, I noticed. I wondered if it was adenoids. ‘Yes,’ he said to Mr Featherstone. ‘Bring Miss Noel over, we’ll have that meeting. Maybe we’ll – ah, run into you again tonight.’

‘Bye, fellas.’ Don stubbed out his cigarette, and winked at me. ‘Miss Noel, my pleasure. Remember to enjoy the sunshine while you’re here. And the butter.’

He touched my arm lightly, then turned around and walked out of the door.

‘Who was that?’ I asked Mrs Featherstone, who was ushering me towards another group of short, suited, bespectacled men.

‘Joe and Lenny Baxter? They’re the heads of Monumental Films, have you really not heard of Monumental Films?’

‘Of course, yes,’ I said. ‘I didn’t realise. That’s – gosh.’ I cleared my throat, trying not to watch Don’s disappearing form. ‘And the writer – Don?’

‘Oh, Don Matthews,’ she said dismissively. ‘Well, he’s a writer. Like they say. I don’t know what he’s doing here, except Don always was good at gatecrashing a party. He drinks.’

‘He wrote Too Many Stars,’ Mr Featherstone said absently, watching the Baxter brothers as they walked slowly away, to be fallen upon by other guests. ‘He’s damn good, when he’s not intoxicated.’

I gasped. ‘Too Many Stars? Oh, I saw that, it must have been four, five times? It’s wonderful! He – he wrote it?’

‘She’s got enough people to memorise without clogging her brain up with nonentities like Don Matthews,’ said Mrs Featherstone, as if I hadn’t spoken. ‘Who’s next?’

‘Well.’ Mr Featherstone scanned the crowd. ‘I wanted to get the Baxters, that’s the prize. If I could put her in front of them they’d see—’ He nodded at me, his expression slightly softening. ‘Honey, you did very well. Make nice with the Baxters if you run into them again, OK? I want them to help us with the picture.’

It was hot, and the smell of lilies and heavy perfume was overwhelming, suddenly. ‘May I be excused for a moment?’ I heard myself say. ‘I’d like to use the – er –’

‘What? Oh, yes, of course.’ Mr and Mrs Featherstone parted in alarm; any reference to reality or, heaven forbid, bodily functions, was abhorrent to them. I’d discovered this the evening I arrived in Los Angeles, tired, bewildered and starving after a flight from London that was exhilarating at first, then terrifying, then just terribly tiring. When we got to the hotel I’d said I felt I might be sick, and both of them had reared back as if I was carrying the bubonic plague.

I slipped through the crowd, past the ladies in their thick silk cocktail dresses, heavy diamonds and rubies and emeralds and sapphires on their honey skin, in their ears, on their fingers – and the gentlemen, all smoking, gathered in knots, talking in low voices. I recognised one ageing matinee idol, his once-black hair greying at the temples and his face puffy with drink, and a vivacious singer, whom I’d read about in a magazine only two weeks ago, nuzzling the neck of an old man who I knew wasn’t her husband, a film actor. But they all had something in common, the guests: they looked as though they were Someone, from the piano player to the lady at the door with the ravaged, over-made-up face. The party was for a producer, thrown by another producer, to celebrate something. I never did find out what, but it was like so many parties I was to go to. It was the first of a template in my new life, though I didn’t know it then. Old-fashioneds and champagne cocktails, delicious little canapés of chicken mousse and tiny cocktail sausages, always a piano player, the air heavy with smoke and rich perfume, the talk all – all, all, all, always the business. Films, movies, the pictures: there was only one topic of conversation.

It was early May. In London winter was over, though it had been raining for weeks by the time I left. But here it was sunny. It was always sunny, the streets lined with beautiful violet-blue blossoms. The air on the terrace outside was a little cooler and I stood there, relief washing over me, glad of the breeze and of this rare solitude. There was a beautiful shell-shaped pool, and I peered into the shimmering turquoise water, looking for something in the reflection. The trees lining the terrace were dark, heavy with a strange green fruit. Idly, I reached up and touched one, and it dropped to the ground, plummeting heavily like a ripe weight. I picked it up, terrified lest anyone should see, and held it. It was shiny, nobbly. I turned it over in my hand.

‘It’s an avocado,’ a voice behind me said.

I jumped, inhaling so sharply that I coughed, and I looked at the speaker. ‘Hello, Mr …’ I stared at him blankly, wildly.

‘It’s Don. Don’t worry about the rest of it. You’re very – er, polite, aren’t you?’ He finished his drink and put it down on a small side table. I watched him.

‘What do you mean, “er, polite”?’

He wrapped his arms around his long lean body, hugging himself in a curiously boyish gesture. ‘Oh, I don’t know. I just met you. You’re awfully on your guard. Like you’re not relaxed.’

I wanted to laugh – how could anyone relax at an evening like this?

‘I – I don’t know,’ I said. ‘Back in London …’

But I didn’t know how to explain it all. Back in London I was always late, I was always losing parts in class to Viola MacIntosh, I never had enough money for the electricity meter, or for a sandwich, and my flatmate Clarissa and I alternated sleeping in the bedroom with its oyster-coloured silk eiderdown that shed a light snowfall of feathers every time you moved in the night, or on the truckle bed in the sitting room, with the springs that pierced your sides, like a religious reproach for our sinful ways.

Whoever I was back then, I wasn’t this person, this cool demure girl, and I knew I was always relaxed. This was my dream, wasn’t it? Training to be an actress. And that’s all I’d ever wanted to do since I was a little girl, playing dress-up with Mother’s evening gowns from the trunk in her dressing room. First with Rose, then by myself after Rose died. There was a brief period during which my increasingly distant parents were concerned about my solitude enough to organise tea parties with other (suitable) children who lived nearby, but it never took. Either I wouldn’t speak or I went and hid. A punishment to myself, you see. If I couldn’t play with Rose, then I wouldn’t play with anyone.

One night, when I was older, I had crept back downstairs to collect my book, and heard their voices in the parlour. I stood transfixed, the soles of my feet stinging cold on the icy Victorian tiled floor. And I remember what my father said.

‘If she’s as good as they say she is, we can’t stand in her way, Marianne. Perhaps it’s what the girl needs. Bring her out of her shell. Teach her how to be a lady, give up this nonsense of pretending Rose is still here.’

My father, so remote from me, so careworn. I looked down at the avocado in my hand. I found it so strange to think of him and Mother now. What would they make of it all? How would I ever describe this to them? But I knew I wouldn’t. When I’d left the cold house by the river eighteen months previously to take up my place at the Central School of Speech and Drama it was as though we said our goodbyes then. I wrote to them and of course I had let them know about my trip to California. But I was nearly twenty. I didn’t need them any more. I don’t know that I ever had, for after Rose died we eventually shrank inwards, each to his or her own world: my father his surgery, my mother her work in the parish church, and I to my own daydreams, playing with the ghost of Rose, acting out fantasies that would never come true.

Mr Featherstone had called my parents himself, to explain who he was. ‘Funny guy, your old pop,’ he’d said. ‘Seemed to not give a fig where you were.’

I couldn’t explain that it was normal for me. I was alone, really, and I had been for years; I’d learnt to live that way.

I felt a touch on my arm, and I looked up to find Don Matthews watching me. He said, ‘It’s a culture shock, I bet, huh?’

‘Something like that.’

He smiled. He had a lopsided grin that transformed his long, kind face. I watched him, thinking abstractly what a nice face it was, how handsome he looked when he smiled. ‘It’s also …’ I took a deep breath, and said in a rush, ‘Don’t think me ungrateful, but I feel a bit like a prize camel. With three humps. Mr Featherstone and his wife are very kind, but I’m never sure if I’m saying what they want me to say.’

‘They don’t want you to say anything. They want you to look pretty and smile at the studio guys in the hope that they’ll give Louis some money to finance the picture. Oh, they say the studios are dying a slow death, but there’s no way Louis will be able to make Helen of Troy without a lot more money than he’s got.’ He reached out to the tree and twisted off another avocado. ‘A camel with three humps, huh? Well, you look fine from where I’m standing.’ He took a penknife out of his pocket, and sliced the thin dark green skin to reveal the creamy green flesh inside, then scooped some and handed it to me. Our fingers touched. I ate it, watching him.

‘It’s delicious,’ I said. ‘Like velvet. And nuts.’

‘It’s perfectly ripe,’ he said. ‘Enjoy it, my dear.’

I nodded, my mind racing.

‘What’s your real name?’ he said, his voice gentle. ‘It’s not Eve Noel, is it?’

I swallowed, blushing slightly at being thus exposed. ‘Sallis. Eve Sallis.’

‘Eve’s a nice name.’

‘I hate it. I wanted to—’ I looked around, weighing up whether to take him into my confidence. ‘I called myself Rose at drama school. Rose Sallis, not Eve. But Mr Featherstone liked Eve, so I’m Eve again.’

‘Why Rose?’

My hands were clenched. ‘It was my sister’s name. She died when I was six.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Don, his face still. ‘You remember her at all?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Very clearly.’ Then, in a rush, ‘She drowned. In the river by our house. It was a strong current and she fell over.’

‘That’s awful. What the hell were you kids doing in there anyway?’

‘It was only her,’ I said, and I blinked. ‘We weren’t allowed. I was chicken.’

‘But she wasn’t.’ His tone was even, not judgemental.

‘Rose was … naughty. Very wild. They said it was dangerous, there’s a weir upstream and the current’s too strong. But she never listened.’ I scrunched my face up. ‘I can see her if I really concentrate. She was older than me, and she’d get so furious with them, shouting, screaming, and sometimes she’d play dead … I thought she was playing dead that time, you see, and I left her to get help, and it was too late …’

It felt so good to be talking about something close to me, to share a piece of my real self with someone, instead of this artifice all the time. Don watched me, a sympathetic expression in his kind dark eyes.

‘You must miss her.’

‘Every day. She was my idol, my sister.’ My shoulders slumped. ‘And they never let me see her afterwards, to say goodbye, you see. I …’ I shook my head. ‘I used to go over everything we did together in my head. So I’d remember. I didn’t have anyone else, you see. She – she was my best friend.’

‘So Rose was like a tribute to her.’ Don sliced another piece of avocado, watching me. ‘That’s nice.’

‘Nice is such a little word, isn’t it,’ I said after a moment’s silence. He raised his eyebrows.

‘You’re right, Miss Noel. It’s not nice. Well, I’m sorry again. Rose, huh? Maybe I should call you Rose.’

‘OK,’ I said, sort of laughing, because it was a strange conversation, yet I felt more comfortable with him than anyone that night.

‘OK, Rose.’ I liked how it sounded when he said it.

‘Can you tell me something?’

‘Of course, Rose. What did you want to know?’

The noise from the party inside washed over towards us. A shriek of hilarity, the sound of men laughing, the distant ringing of a bell.

‘What happens if I don’t stay quiet?’ I said. ‘What about if I tell them I’ve made a mistake and I want to go home?’

‘Do you think that?’

I breathed out. ‘Um – no.’ My throat felt tight all of a sudden. ‘I’m not sure. It’s been two weeks and …’ I swallowed. ‘This is stupid. I’m homesick, I suppose. It’s such a different world.’

The sky above us was that peculiar electrifying deep blue, just before the moon appears. He took my hand. His skin was warm and his fingers on mine strangely comforting, even though he was a stranger. ‘Hey,’ he said. ‘Look at the stars above you.’ I looked up. ‘And the fruit on the trees, the smell of money in the air. You’re in California. You were chosen to come here. You’re going to star in what could be the biggest picture of the year. I know Louis can come off as a jerk, but he knows what he’s doing, trust me.’ He shrugged. ‘This is the break thousands of girls dream about.’

‘I know,’ I said. I wished I could put my head on his shoulder. I could smell tobacco and something else on his jacket, a woody, comforting smell. ‘And I can’t go home. The thought of going back to London with my tail between my legs. And seeing my parents – explaining to them.’ I stood up straight. ‘I have to get on with it. Stiff upper lip, and all that.’

‘You British,’ he said. He released my hand. ‘Where’s home, then?’

How did I explain I didn’t really have a home? ‘Oh, it’s a village in the middle of the countryside. But I was at drama school, in London. I was living in a place called Hampstead. That was really my home.’

‘I’ve always wanted to go to Hampstead. Oh, yes,’ Don said, smiling at my surprise. ‘My father was a teacher. Taught me every poem Keats ever wrote.’ I must have looked completely blank, because he said, ‘Keats lived in Hampstead, you little philistine. I thought you Brits grew up on the stuff.’

I shrugged. ‘He didn’t write plays. I like playwrights.’

Don leaned his lanky body against the tree, sliced a little more avocado, and said, ‘How about screenwriters?’

I smiled. ‘I like them too, I suppose.’

‘I’m glad to hear it,’ he replied.

‘There you are, Eve.’ Mr Featherstone came waddling out onto the terrace. ‘I was wondering where you’d got to.’

‘I’m so sorry,’ I said guiltily. ‘I met Don – Mr Matthews – again, and we were—’

‘I was monopolising your star,’ Don said smoothly. ‘I should let you go.’

‘No, I don’t want to interrupt,’ Mr Featherstone said genially, wiping his moist brow with a handkerchief. ‘Eve, I wanted you to meet the head of publicity for Monumental, Moss Fisher. He’s a great guy, and if he likes you too I really think the Monumental deal’s in the bag.’ He smiled at me. ‘Joe Baxter liked you, honey. Really liked you. He wants us to go out to dinner with him. So I’m gonna take you to meet Moss now and then we’re going to Ciro’s. You’ll love it.’ He looked at Don. ‘Won’t she, Don?’

‘Depends,’ Don said. ‘But yes, I think she might like it. If she makes up her mind it’s what she wants.’

The shade from the tree was black. I couldn’t see his face. ‘Well,’ I said. ‘Goodbye – and thank you.’

‘It was my pleasure,’ he said. ‘Hey, do something for me, will you? Try and enjoy it.’

He moved away and I suddenly realised I might not see him again. I don’t know why but I called after him, ‘I loved Too Many Stars. It’s my favourite film.’

He stopped and turned around, one half of his slim body golden in the light from the hallway, the party. ‘Thank you,’ he said. ‘Thank you, Rose.’

He disappeared through the door and then he was gone.

‘Did you tell Don Matthews to call you Rose?’ Mr Featherstone said, a note of displeasure in his voice as he steered me back inside. ‘Why would you do that?’

‘I – it’s – oh, we were having a joke.’ But then the guilt I always felt deepened some more, as though I thought Rose was something to joke about. ‘I’m sorry, I won’t do it again,’ I said, more to myself than to him.

‘It takes time to learn these things,’ he said. ‘You’ve done very well, my dear.’ His eyes ranged over my dress again. ‘Now, here’s Mr Baxter. And Mr Fisher. Be nice. Moss, hey! This is the little lady I was telling you about. Eve dear, this is Moss Fisher.’

Out of the shadows stepped another man, thin and even shorter than the Baxters. His thick curling hair was smoothed down with Brylcreem or something that made it look wet. His dark eyes darted from side to side, then stared coldly at me. He nodded.

‘Hi,’ he said, to no one in particular.

‘Hello, Mr Fisher,’ I said politely.

He didn’t acknowledge this, but turned to Joe Baxter. ‘The teeth need fixing, Joe.’

‘Yes, I know,’ Mr Baxter said under his breath. ‘Still though—’

‘How old are you?’ Moss Fisher asked, almost uninterestedly.

‘I’m – I’m nearly twenty.’

He nodded. ‘Maybe it’s worth it,’ he said. He shrugged. ‘The hairline, too. It’s awful but they can change it. Do a screen test. I’m going, Joe. See ya tomorrow.’

Joe Baxter rose a hand in farewell as Moss Fisher walked away.

‘Don’t mind Moss,’ he said jovially. ‘He’s all business. A great guy, a great guy, isn’t he, Louis?’

‘Oh, yes,’ said Mr Featherstone. He stared at my hair in annoyance. I put my hand up to my brow, self-conscious.