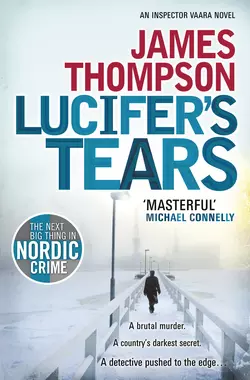

Lucifer’s Tears

James Thompson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Триллеры

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.42 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: His previous case left Kari Vaara with a scarred face, chronic insomnia and a full body count′s worth of ghosts. A year later, in Helsinki, and Kari is working the graveyard shift in the homicide unit.Kari is drawn into the murder-by-torture case of Isa Filippov, the philandering wife of a Russian businessman. Her lover is clearly being framed and while Ivan Filippov′s arrogance is highly suspicious, he′s got friends in high places. Kari is sucked ever deeper and soon the past and present collide in ways no one could have anticipated…Discover the hottest new voice in Scandinavian crime-writing – if you love Jo Nesbo and Stieg Larsson you’ll love James Thompson.