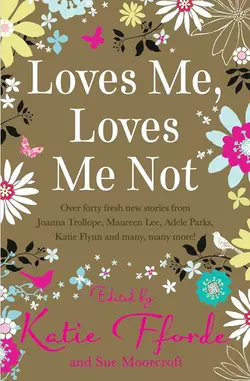

Loves Me, Loves Me Not

Romantic Association

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Indulge yourself…With over forty stories to choose from, this fabulous collection has something for everyone – from bittersweet holiday flings to emotional family weepies; from fun chick-lit tales to Regency romances – Loves Me, Loves Me Not is a true celebration of the very best in romantic fiction.Read all-new stories from the bestselling authors of today and discover the bestselling authors of tomorrow.