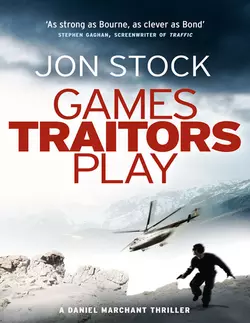

Games Traitors Play

Jon Stock

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 697.21 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Re-inventing the spy story for the 21st Century.John Le Carre meets Jason Bourne!Salim Dhar is the world′s most wanted terrorist. The CIA is under pressure to hunt him down, after he narrowly failed to kill the US president. The borders of Afghanistan and Pakistan are the target of relentless drone strikes. Echelon, the West′s intelligence analysis network, is in meltdown, monitoring all channels for the faintest trace of Dhar. But no one can find him. Only Daniel Marchant, renegade MI6 officer, knows where he is.Marchant has been living in Marrakech, listening to the traditional Berber storytellers as they enthral tourists with tales from The Arabian Nights. Marchant believes that Dhar has shunned technology, retreating to old customs:coded messages for Dhar are being embedded in ancient narratives.When a man flees from the square, Marchant pursues him up into the Atlas Mountains, where he sees an unmarked military helicopter take off and head east. Is someone shielding Dhar to perpetrate an act of proxy terrorism on the West? Or is the CIA right when it claims to have killed him?To discover the truth, Marchant must be recruited by Moscow. But Marcus Fielding, erudite Chief of MI6, doubts that his young intelligence officer has the mental strength to be a double agent. It′s a role that will require him to believe his late father was a traitor, an allegation that Marchant fought long and hard to dispel. Now he must rekindle those rumours and confront dark truths about his own loyalties. He must also work with Lakshmi Meena, the CIA′s beautiful new liaison officer in London. Can he ever trust a woman-or an American-again after being betrayed by her predecessor?As Britain braces itself for an airborne terrorist attack, Marchant survives torture in Morocco and India in his bid to find and stop Dhar. Will family ties ultimately prove more binding than ideology? In an absorbing thriller that combines the nuances of Cold War Le Carre with the ejector-seat excitement of Top Gun, Marchant discovers that treachery is the greatest game of all.