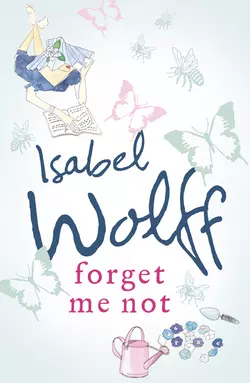

Forget Me Not

Isabel Wolff

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The sparkling new novel from the bestselling author of ‘A Question of Love.’ Perfect for fans of Jane Green.After the sudden death of her mother, Anna Temple realises she needs to live for the moment and pursue her dream of becoming a garden designer. Swapping hedge funds for herbaceous borders, she says goodbye to City life for a fresh start in the country.But on the eve of her sparkling new future she meets the gorgeous Xan and their chance encounter changes her world in more ways than she could ever imagined – enter baby Milly.Juggling her new business with the joys and fears of motherhood alone is a struggle, and when Anna unearths a long-buried family secret, skeletons tumble from the closet. Suddenly nothing is as it seems, past or present…