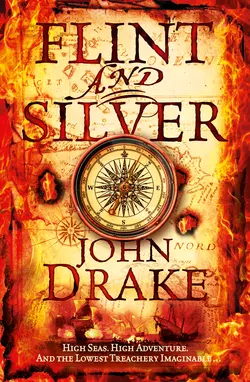

Flint and Silver

John Drake

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фэнтези про драконов

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Rip-roaring adventures for fans of ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ and Patrick O’ Brian, in these pirate prequels to ‘Treasure Island’.