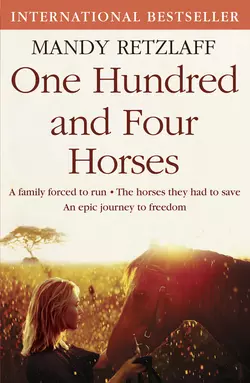

One Hundred and Four Horses

Mandy Retzlaff

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1167.87 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘A letter is handed to you. In broken English, it tells you that you must now vacate your farm; that this is no longer your home, for it now belongs to the crowd on your doorstep. Then the drums begin to beat.’As the land invasions gather pace, the Retzlaffs begin an epic journey across Zimbabwe, facing eviction after eviction, trying to save the group of animals with whom they feel a deep and enduring bond – the horses.When their neighbours flee to New Zealand, the Retzlaffs promise to look after their horses, and making similar promises to other farmers along their journey, not knowing whether they will be able to feed or save them, they amass an astonishing herd of over 300 animals. But the final journey to freedom will be arduous, and they can take only 104 horses.Each with a different personality and story, it is not just the family who rescue the horses, but the horses who rescue the family. Grey, the silver gelding: the leader. Brutus, the untamed colt. Princess, the temperamental mare.One Hundred and Four Horses is the story of an idyllic existence that falls apart at the seams, and a story of incredible bonds – a love of the land, the strength of a family, and of the connection between man and the most majestic of animals, the horse.