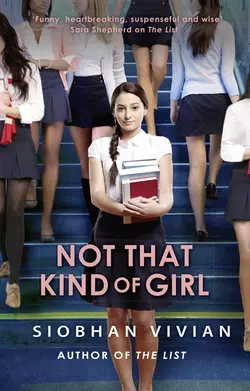

Not That Kind Of Girl

Siobhan Vivian

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Книги для подростков

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 467.61 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Slut or saint? Good friend or bad friend? In control or completely out of it?She′s avoided boys, always topped her class and is poised to become the first female student council president in years.But being the good girl isn′t always easy. Not when Natalie’s advice hurts more than it helps. Not when a boy she once dismissed becomes the one she can′t stop thinking about.Soon Natalie’s learning that the line between good and bad is fuzzier than she thought and crossing it could end in disaster . . . or be the best choice she’s ever made.