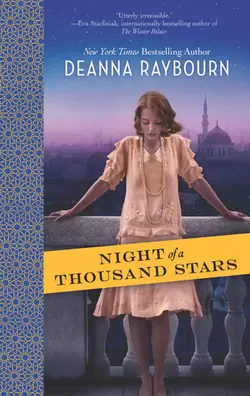

Night of a Thousand Stars

Night of a Thousand Stars

Deanna Raybourn

New York Times bestselling author Deanna Raybourn returns with a Jazz Age tale of grand adventure

On the verge of a stilted life as an aristocrat's wife, Poppy Hammond does the only sensible thingshe flees the chapel in her wedding gown. Assisted by the handsome curate who calls himself Sebastian Cantrip, she spirits away to her estranged father's quiet country village, pursued by the family she left in uproar. But when the dust of her broken engagement settles and Sebastian disappears under mysterious circumstances, Poppy discovers there is more to her hero than it seems.

With only her feisty lady's maid for company, Poppy secures employment and travels incognitaeast across the seas, chasing a hunch and the whisper of clues. Danger abounds beneath the canopies of the silken city, and Poppy finds herself in the perilous sights of those who will stop at nothing to recover a fabled ancient treasure. Torn between allegiance to her kindly employer and a dashing, shadowy figure, Poppy will risk it all as she attempts to unravel a much larger plan - one that stretches to the very heart of the British government, and one that could endanger everything, and everyone, that she holds dear.

Raybourn skillfully balances humor and earnest, deadly drama, creating well-drawn characters and a rich setting. Publishers Weekly on Dark Road to Darjeeling

New York Times bestselling author Deanna Raybourn returns with a Jazz Age tale of grand adventure

On the verge of a stilted life as an aristocrat’s wife, Poppy Hammond does the only sensible thing—she flees the chapel in her wedding gown. Assisted by the handsome curate who calls himself Sebastian Cantrip, she spirits away to her estranged father’s quiet country village, pursued by the family she left in uproar. But when the dust of her broken engagement settles and Sebastian disappears under mysterious circumstances, Poppy discovers there is more to her hero than it seems.

With only her feisty lady’s maid for company, Poppy secures employment and travels incognita—east across the seas, chasing a hunch and the whisper of clues. Danger abounds beneath the canopies of the silken city, and Poppy finds herself in the perilous sights of those who will stop at nothing to recover a fabled ancient treasure. Torn between allegiance to her kindly employer and a dashing, shadowy figure, Poppy will risk it all as she attempts to unravel a much larger plan—one that stretches to the very heart of the British government, and one that could endanger everything, and everyone, that she holds dear.

“Raybourn skillfully balances humor and earnest, deadly drama, creating well-drawn characters and a rich setting.”

—Publishers Weekly on Dark Road to Darjeeling

Praise for the novels of Deanna Raybourn (#ulink_b76fe9a7-fc99-5c3b-8bf5-061eae820a6e)

“Raybourn’s first-class storytelling is evident…

Readers will quickly find themselves embarking on an

unforgettable journey that fans both old and new are sure to savor.”

—Library Journal on City of Jasmine

“With a strong and unique voice, Deanna Raybourn

creates unforgettable characters in a richly detailed world.

This is storytelling at its most compelling.”

—Nora Roberts, #1 New York Times bestselling author

“Raybourn skillfully balances humor and earnest, deadly drama, creating well-drawn characters and a rich setting.”

—Publishers Weekly on Dark Road to Darjeeling

“A great choice for mystery, historical fiction and/or romance readers.”

—Library Journal on Silent on the Moor

“Raybourn…delightfully evokes the language, tension

and sweeping grandeur of 19th-century gothic novels.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Dead Travel Fast

“Raybourn expertly evokes late-nineteenth-century colonial India

in this rollicking good read, distinguished by its delightful lady detective and her colorful family.”

—Booklist on Dark Road to Darjeeling

“[A] perfectly executed debut… Deft historical detailing

[and] sparkling first-person narration.”

—Publishers Weekly on Silent in the Grave, starred review

“A sassy heroine and a masterful, secretive hero. Fans of

romantic mystery could ask no more—except the promised sequel.”

—Kirkus Reviews on Silent in the Grave

Also by Deanna Raybourn (#ulink_e83ad8a1-ec6d-5826-95eb-0444dc96ae64)

Historical Fiction

City of Jasmine

Whisper of Jasmine*

A Spear of Summer Grass

Far in the Wilds*

The Lady Julia Grey series

Silent in the Grave

Silent in the Sanctuary

Silent on the Moor

The Dead Travel Fast

Dark Road to Darjeeling

The Dark Enquiry

Silent Night*

Midsummer Night*

Twelfth Night*

And watch for Bonfire Night*, available soon from Harlequin MIRA!

*Digital Novellas

Night of a

Thousand

Stars

Deanna Raybourn

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For Caitlin—

another beautiful girl from an eccentric family making her way in the world.

They would have reached the nursery in time had it not been that the little stars were watching them. Once again the stars blew the window open, and that smallest star of all called out:

“Cave, Peter!”

Then Peter knew that there was not a moment to lose.

“Come,” he cried imperiously, and soared out at once into the night, followed by John and Michael and Wendy.

Mr. and Mrs. Darling and Nana rushed into the nursery but it was too late. The birds were flown.

—Peter and Wendy, J. M. Barrie

Contents

Cover (#u5ce48210-89ff-5c66-81a7-3b5deb46157c)

Back Cover Text (#ueb471609-dc23-5761-a582-cc810d685d42)

Praise (#uba19290f-0229-541b-931f-b9681eafbdcf)

Booklist (#u922af244-4645-5bae-803d-fb4676d1ede5)

Title Page (#u0f2f3997-ab1c-541c-852c-39297c6dec17)

Dedication (#uf29b6485-a6cd-55c1-8358-bbf429f06e9d)

Quote (#u426144f0-8a1f-5aa1-bb57-4a3e54536429)

One (#u64e94034-f400-58e6-8717-a96f99104244)

Two (#ue4343bfa-5576-5872-96eb-9e34b2662ee6)

Three (#uc6997879-4392-5864-b508-7d34f1fdaafa)

Four (#ub9ce5f2f-d874-580c-9d7b-2d24c4588614)

Five (#u8bed14f4-420d-51d5-8bc4-5d0c89b3a0ef)

Six (#ucd4d0242-6629-5690-9a48-697a5f3e4d42)

Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Reader’s Guide (#litres_trial_promo)

Questions for Discussion (#litres_trial_promo)

A Conversation with Deanna Raybourn (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

One (#ulink_7be97a9f-e491-5abe-bfb4-83c49c4a864f)

March 1920

“I say, if you’re running away from your wedding, you’re going about it quite wrong.”

I paused with my leg out the window, satin wedding gown hitched up above my knees. A layer of tulle floated over my face, obscuring my view. I shoved it aside to find a tall, bespectacled young man standing behind me. His expression was serious, but there was an unmistakable gleam in his eyes that was distinctly at odds with his clerical garb.

“Oh! Are you the curate? I know you can’t be the vicar. I met him last night at the rehearsal and he’s simply ancient. Looks like Methuselah’s godfather. You’re awfully young to be a priest, aren’t you?” I asked, narrowing my eyes at him.

“But I’m wearing a dog collar. I must be,” he protested. “And as I said, if you’re running away, you’ve gone about it quite stupidly.”

“I have not,” I returned hotly. “I managed to elude both my mother and my future mother-in-law, and if you think that was easy, I’d like to sell you a bridge in Brooklyn.”

“Brooklyn? Where on earth is that?”

I rolled my eyes heavenward. “New York. Where I live.”

“You can’t be American. You speak properly.”

“My parents are English and I was educated here—oh, criminy, I don’t have time for this!” I pushed my head out the window, but to my intense irritation, he pulled me back, his large hands gently crushing the puffed sleeves of my gown.

“You haven’t thought this through, have you? You can get out the window easily enough, but what then? You can’t exactly hop on the Underground dressed like that. And have you money for a cab?”

“I—” I snapped my mouth shut, thinking furiously. “No, I haven’t. I thought I’d just get away first and worry about the rest of it later.”

“As I said, not a very good plan. Where are you bound, anyway?”

I said nothing. My escape plan was not so much a plan as a desperate flight from the church as soon as I heard the organist warming up the Mendelssohn. I was beginning to see the flaw in that thinking thanks to the helpful curate. “Surely you don’t intend to go back to the hotel?” he went on. “All your friends and relations will go there straight away when they realise you’ve gone missing. And since your stepfather is Reginald Hammond—”

I brandished my bouquet at him, flowers snapping on their slender stems. “Don’t finish that sentence, I beg you. I know exactly what will happen if the newspapers get hold of the story. Fine. I need a place to lie low, and I have one, I think, but I will need a ride.” I stared him down. “Do you have a motorcar?”

He looked startled. “Well, yes, but—”

“Excellent. You can drive me.”

“See here, Miss Hammond, I don’t usually make a habit of helping runaway brides to abscond. After all, from what I hear Mr. Madderley is a perfectly nice fellow. You might be making a frightful mistake, and how would it look to the bishop if I aided and abetted—”

“Never mind!” I said irritably. I poked my head through the window again, and this time when he retrieved me he was almost smiling, although a slim line of worry still threaded between his brows.

“All right then, I surrender. Where are you going?”

I pointed in the direction I thought might be west. “To Devon.”

He raised his brows skyward. “You don’t ask for much, do you?”

“I’ll go on my own then,” I told him, setting my chin firmly. Exactly how, I had no idea, but I could always think of that later.

He seemed to be wrestling with something, but a sound at the door decided him. “Time to get on. My motorcar is parked just in the next street. I’ll drive you to Devon.”

I gave him what I hoped was a dazzling smile. “Oh, you are a lamb, the absolute bee’s knees!”

“No, I’m not. But we won’t quarrel about that now. I locked the door behind me but someone’s rattling the knob, and I give them about two minutes before they find the key. Out you go, Miss Hammond.”

Without a further word, he shoved me lightly through the window and I landed in the shrubbery. I smothered a few choice words as I bounced out of his way. He vaulted over the windowsill and landed on his feet—quite athletically for a clergyman.

“That was completely uncalled-for—” I began, furiously plucking leaves out of the veil.

He grabbed my hand and I stopped talking, as surprised by the gesture as by the warmth of his hand.

“Come along, Miss Hammond. I think I hear your mother,” he said.

I gave a little shriek and began to run. At the last moment, I remembered the bouquet—a heavy, spidery affair of lilies and ivy that I detested. I flung it behind us, laughing as I ran.

* * *

“I shouldn’t have laughed,” I said mournfully. We were in the motorcar—a chic little affair painted a startling shade of bright blue—and the curate was weaving his way nimbly through the London traffic. He seemed to be listening with only half an ear.

“What was that?”

“I said I shouldn’t have laughed. I mean, I feel relieved, enormously so, if I’m honest, but then there’s Gerald. One does feel badly about Gerald.”

“Why? Will you break his heart?”

“What an absurd question,” I said, shoving aside the veil so I could look the curate fully in the face. “And what a rude one.” I lapsed into near-silence, muttering to myself as I unpicked the pins that held the veil in place. “I don’t know,” I said after a while. “I mean, Gerald is so guarded, so English, it’s impossible to tell. He might be gutted. But he might not. He’s just such a practical fellow—do you understand? Sometimes I had the feeling he had simply ticked me off a list.”

“A list?” The curate dodged the little motorcar around an idling lorry, causing a cart driver to abuse him loudly. He waved a vague apology and motored on. For a curate, he drove with considerable flair.

“Yes. You know—the list of things all proper English gentlemen are expected to do. Go to school, meet a suitable girl, get married, father an heir and a spare, shoot things, die quietly.”

“Sounds rather grim when you put it like that.”

“It is grim, literally so in Gerald’s case. He has a shooting lodge in Norfolk called Grimfield. It’s the most appalling house I’ve ever seen, like something out of a Brontë novel. I half expected to find a mad wife locked up in the attic or Heathcliff abusing someone in the stables.”

“Did you?”

“No, thank heavens. Nothing but furniture in the attic and horses in the stables. Rather disappointingly prosaic, as it happens. But the point is, men like Gerald have their lives already laid out for them in a tidy little pattern. And I’m, well, I’m simply not tidy.” I glanced at the interior of the motorcar. Books and discarded wellies fought for space with a spare overcoat and crumpled bits of greaseproof paper—the remains of many sandwich suppers, it seemed. “You’re untidy too, I’m glad to see. I always think a little disorder means a creative mind. And I have dreams of my own, you know.” I paused then hurried on, hoping he wouldn’t think to ask what those dreams might be. I couldn’t explain them to him; I didn’t even understand them myself. “I realised with Gerald, my life would always take second place. I would be his wife, and eventually Viscountess Madderley, and then I would die. In the meantime I would open fêtes and have his children and perhaps hold a memorable dinner party or two, but what else? Nothing. I would have walked into that church today as Penelope Hammond and walked out as the Honourable Mrs. Gerald Madderley, and no one would have remembered me except as a footnote in the chronicles of the Madderley family.”

“Quite the existential crisis,” he said lightly. I nodded.

“Precisely. I’m very glad you understand these things.” I looked around again. “I don’t suppose you have a cigarette lying about anywhere? I’d very much like one.”

He gestured towards the glovebox and I helped myself. As soon as I opened it, an avalanche of business cards, tickets, receipts and even a prayer book fell out. I waved a slip of paper at him. “You haven’t paid your garage bill,” I told him. “Second notice.”

He smiled and pocketed the paper. “Slipped my mind. I’ll take care of it tomorrow.”

I shovelled the rest of the detritus back into the glovebox, and he produced a packet of matches. I pulled out a cigarette and settled back then gave a little shriek of dismay. “Heavens, where are my manners? I forgot to ask if you wanted one.”

He shook his head. “I don’t indulge.”

I cocked my head. “But you keep them around?”

“One never knows when they’ll be in demand,” he said. “How long have you had the habit?”

“Oh, I don’t. It just seems the sort of thing a runaway bride ought to do. I’ll be notorious now, you know.”

I gave the unlit cigarette a sniff. “Heavens, that’s foul. I think I shall have to find a different vice.” I dropped the cigarette back into the packet.

He smiled but said nothing and we lapsed into a comfortable silence.

I studied him—from the unlined, rather noble brow to the shabby, oversized suit of clothes with the shiny knees and the unpolished shoes. There was something improbable about him, as if in looking at him one could add two and two and never make four. There was an occasional, just occasional, flash from his dark eyes that put me in mind of a buccaneer. He was broad-shouldered and athletic, but the spectacles and occupation hinted he was bookish.

There were other contradictions as well, I observed. Being a curate clearly didn’t pay well, but the car was mint. Perhaps he came from family money, I surmised. Or perhaps he had a secret gambling habit. I gave him a piercing look. “You don’t smoke. Do you have other vices? Secret sins? I adore secrets.”

Another fellow might have taken offence but he merely laughed. “None worth talking about. Besides, we were discussing you. Tell me,” he said, smoothly negotiating a roundabout and shooting the motorcar out onto the road towards Devon, “what prompted this examination of your feelings? It couldn’t be just the thought of marrying him. You’ve had months to accustom yourself to the notion of being the future Viscountess Madderley. Why bolt now?”

I hesitated, feeling my cheeks grow warm. “Well, I might as well tell you. You are a priest, after all. It would be nice to talk about it, and since you’re bound by the confessional, it would be perfectly safe to tell you because if you ever tell anyone you’ll be damned forever.”

His lips twitched as if he were suppressing a smile. “That isn’t exactly how it works, you know.”

I flapped a hand. “Close enough. I always had doubts about Gerald, if I’m honest. Ever since he asked me to dance at the Crichlows’ Christmas ball during the little season. He was just so staid, as if someone had washed him in starch rather than his clothes. But there were flashes of something more. Wit or kindness or gentleness, I suppose. Things I thought I could bring out in him.” I darted a glance at the curate. “I see now how impossibly stupid that was. You can’t change a man. Not unless he wants changing, and what man wants changing? The closer the wedding got, the more nervous I became and I couldn’t imagine why I wasn’t entirely over the moon about marrying Gerald. And then my aunt sent me a book that made everything so clear.”

“What book?”

“Mrs. Stopes’ book, Married Love.”

“Oh, God.” He swerved and neatly corrected, but not before I gave him a searching look.

“I’ve shocked you.” Most people had heard of the book, but few had read it. It had been extensively banned for its forthright language and extremely modern—some would say indecent—ideas.

He hurried to reassure me. “No, no. Your aunt shocked me. I wouldn’t imagine most ladies would send an affianced bride such a book.”

“My aunt isn’t most ladies,” I said darkly. “She’s my father’s sister, and they’re all eccentric. They’re famous for it, and because they’re aristocrats, no one seems to mind. Of course, Mother nearly had an apoplexy when she found the book, but I’d already read it by that point, and I knew what I had to do.”

“And what was that?”

“I had to seduce Gerald.”

This time the curate clipped the edge of a kerb, bouncing us hard before he recovered himself and steered the motorcar back onto the road.

“I shocked you again,” I said sadly.

“Not in the slightest,” he assured me, his voice slightly strangled. He cleared his throat, adopting a distinctly paternal tone in spite of his youth. “Go on, child.”

“Well, it was rather more difficult to arrange than I’d expected. No one seems to want to leave you alone when you’re betrothed, which is rather silly because whatever you get up to can’t be all that bad because you’re with the person you’re going to be getting up to it with once you’re married, and it’s all right then. And isn’t it peculiar that just because a priest says a few words over your head, the thing that was sinful and wrong is suddenly perfectly all right? No offence to present company.”

“None taken. It does indeed give one pause for thought. You were saying?”

“Oh, the arrangements. Well, I couldn’t manage it until a fortnight ago. By that time I was fairly seething with impatience. I’m sorry—did you say something?”

“Not at all. It was the mental image of you seething with impatience. It was rather distracting.”

“Oh, I am sorry. Should we postpone this discussion for another time? When you’re not driving perhaps?”

“No, indeed. I promise you this is the most interesting discussion I’ve had in a very long while.”

“And you’re still not shocked?” I asked him. I was feeling a bit anxious on that point. I had a habit of engaging in what Mother called Inappropriate Conversation. The trouble was, I never realised I was doing it until after the fact. I was always far too busy enjoying myself.

“Not in the slightest. Continue—you were seething.”

“Yes, I was in an absolute fever, I was so anxious. We were invited to the Madderleys’ main estate in Kent—a sort of ‘getting to know you’ affair between the Madderleys and the Hammonds. It was very gracious of Gerald’s mother to suggest it, although now that I think about it, it wasn’t so much about the families getting to know one another as about the viscount and my stepfather discussing the drains and the roofs and how far my dowry would go to repairing it all.”

I stopped to finish unpinning the veil and pulled it free, tearing the lace a little in my haste. I shoved my hands through my hair, ruffling up my curls and giving a profound sigh. “Oh, that’s better! Pity about the veil. That’s Belgian lace, you know. Made by nuns, although why nuns should want to make bridal veils is beyond me. Anyway, the gentlemen were discussing the money my dowry would bring to the estate, and the ladies were going on about the children we were going to have and what would be expected of me as the future viscountess. Do you know Gerald’s mother even hired my lady’s maid? Masterman, frightful creature. I’m terrified of her—she’s so efficient and correct. Anyway, I suddenly realised that was going to be the rest of my life—doing what was perfectly proper at all times and bearing just the right number of children—and I was so bored with it all I nearly threw myself in front of a train like Anna Karenina just to be done with it. I couldn’t imagine actually living in that draughty great pile of stone, eating off the same china the Madderleys have been using since the time of Queen Anne. But I thought it would all be bearable if Gerald and I were compatible in the Art of Love.”

“The Art of Love?”

“That’s what Mrs. Stopes called it in Married Love. She says that no matter what differences a couple might have in religion or politics or social customs, if they are compatible in the Art of Love, all may be adjusted.”

“I see.” He sounded strangled again.

“So, one night after everyone had retired, I crept to Gerald’s room and insisted we discover if we were mutually compatible.”

“And were you?”

“No,” I said flatly. “I thought it was my fault at first. But I chose the date so carefully to make sure my sex-tide would be at its highest.”

“Your sex-tide?”

“Yes. Really, you ought to know these things if you mean to counsel your parishioners. The achievement of perfect marital harmony only comes with an understanding of the sex-tides—the ebb and flow of a person’s desires and inclinations for physical pleasure.”

He cleared his throat lavishly. “Oh, the sex-tides. Of course.”

“In any event, Gerald and I were most definitely not compatible.” I paused then plunged on. “To begin with, he wouldn’t even take off his pyjamas when we were engaged in the Act of Love.”

The curate’s lips twitched into a small smile. “Now that shocks me.”

“Doesn’t it? What sort of man wants a barrier of cloth between himself and the skin of his beloved? I have read the Song of Solomon, you know. It’s a very informative piece of literature and it was quite explicit with all the talk of breasts like twin fawns and eating of the secret honeycomb and honey. I presume you’ve read the Song of Solomon? It is in the Bible, after all.”

“It is,” he agreed. “Quite the most interesting book, if you ask me.” Again there was a flash of something wicked as he shot me a quick look. “So, was your betrothed a young god with legs like pillars of marble and a body like polished ivory?”

I pulled a face. “He was not. That was a very great disappointment, let me tell you. And then it was over with so quickly—I mean, I scarcely had time to get accustomed to the strangeness of it because, let’s be frank, there is something so frightfully silly about doing that, although you probably don’t know yourself, being a member of the clergy and all. But before I could quite get a handle on things, it was finished.”

“Finished?” he said, his hands tight on the steering wheel.

“Finished. At least, Gerald was,” I added sulkily. “He gave a great shudder and made an odd sort of squeaking sound.”

“Squeaking sound?”

“Yes.” I tipped my head, thinking. “Like a rabbit that’s just seen a fox. And then he rolled over and went to sleep just like that.”

“Philistine,” he pronounced.

“Then you do understand! How important the physical side of marriage is, I mean. Particularly with a husband like Gerald. One would need a satisfactory time in the bedroom to make up for—” I clapped a hand to my mouth. He smiled then, indulgently, and I dropped my hand, but I still felt abashed. “Oh, that was unkind. Gerald has many sterling attributes. Sterling,” I assured him.

“Sterling is what one wants out of one’s silver. Not a husband,” he said mildly.

I sighed in contentment. “You are good at this. You understand. And you haven’t made me feel guilty over the sin of it, although you mustn’t tell anyone, but I don’t really believe in sin at all. I know that’s a wicked thing to say, but I think all God really expects is a little common sense and kindness out of us. Surely He’s too busy to keep a tally of all our misdeeds. That would make Him nothing more than a sort of junior clerk with a very important sense of Himself, wouldn’t it?”

“I suppose.”

“Oh, I know you can’t agree with me. You make your career on sin, just as much as anybody who sells liquor or naughty photographs. Sin is your bread and butter.”

“You have a unique way of looking at the world, Miss Hammond.”

“I think it’s because I’ve been so much on my own,” I told him after a moment. “I’ve had a lot of time to think things over.”

“Why have you been so much on your own?” he asked. His voice was gentler than it had been, and the air of perpetual amusement had been replaced by something kinder, and it seemed as if he were genuinely interested. It was a novel situation for me. Most people who wanted to talk to me did so because of my stepfather’s money.

“Oh, didn’t you know? Apparently it was a bit of a scandal at the time. It was in all the newspapers and of course they raked it all up again when I became engaged to Gerald. My parents divorced, and Mother took me to America when she left my father. I was an infant at the time, and apparently he let her take me because he knew it would utterly break her heart to leave me behind. He stayed in England and she went off to America. We’re practically strangers, Father and I. He’s always been a bit of a sore spot to Mother, even though she did quite well out of it all. She married Mr. Hammond—Reginald. He’s a lovely man, but rather too interested in golf.”

“Lots of gentlemen play,” he remarked. His hands were relaxed again, and he opened the car up a little, guiding it expertly as we fairly flew down the road.

“Oh, Reginald doesn’t just play. He builds golf courses. Designing them amuses him, and after he made his millions in copper, he decided to travel around the world, building golf courses. Places like Florida, the Bahamas. He’s quite mad about the game—he even named his yacht the Gutta-Percha, even though no one uses gutta-percha balls anymore.”

He shook his head as if to clear it and I gave him a sympathetic look. “Do you need me to read maps or something? It must be fatiguing to drive all this way.”

“The conversation is keeping me entirely alert,” he promised.

“Oh, good. Where was I?”

“Reginald Hammond doesn’t have gutta-percha balls,” he replied solemnly. If he had been one of my half-brothers, I would have suspected him of making an indelicate joke, but his face was perfectly solemn.

“No one does,” I assured him. “Anyway, he’s a lovely man but he isn’t really my father. And when the twins came along, and then the boys, well, they had their own family, didn’t they? It was nothing to do with me.” I fell silent a moment then pressed on, adopting a firmly cheerful tone. “Still, it hasn’t been so bad. I thoroughly enjoyed coming back here to go to school, and I have found my father.”

“You’ve seen him?” he asked quickly.

“No. But I made some inquiries, and I know where he is. He’s a painter,” I told him. I was rather proud of the little bit of detection I had done to track him down. “We wrote letters for a while, but he travelled extensively—looking for subjects to paint, I suppose. He gave me a London address in Half Moon Street to send the letters, but he didn’t actually live there. You know, it’s quite sad, but I always felt so guilty when his letters came. Mother would take to her bed with a bottle of reviving tonic every time she saw his handwriting in the post. I didn’t dare ask to invite him to the wedding. She would have shrieked the house down, and it did seem rather beastly to Reginald since he was paying for it. Still, it is peculiar to have an entire family I haven’t met. Some of them kept in touch—my Aunt Portia, for one. She sent me the copy of Married Love. When I came to England for the little season, I asked her where Father was. She promised not to tell him I’d asked, but she sent me his address. He has a house in Devon. He likes the light there, something about it being good for his work.”

“I see.”

“It’s very kind of you to drive me,” I said, suddenly feeling rather shy with this stranger to whom I had revealed entirely too much. “Oh!” I sat up very straight. “I don’t even know your name.”

“Sebastian. My name is Sebastian Cantrip.”

“Cantrip? That’s an odd name,” I told him.

“No odder than Penelope.”

I laughed. “It’s Greek, I think. My mother’s choice. She thought it sounded very elegant and educated. But my father called me Poppy.”

Sebastian slanted me a look. “It suits you better.”

“I think so, but when I was presented as a debutante, Mother insisted on calling me Penelope Hammond. Hammond isn’t my legal name, you know. It gave me quite a start to see the name on the invitations to the wedding. Mr. and Mrs. Reginald Hammond cordially invite you to the wedding of their daughter, Penelope Hammond. But I’m not Penelope Hammond, not really.” I lifted my chin towards the road rising before us. “I’m Poppy March.”

“Well, Poppy March, I suggest you rest a bit. We’ve a long drive ahead of us, and you must be exhausted.”

I snuggled down into the seat, eyelids drooping, then bolted up again. “You’re sure you don’t need me? I am an ace reader of maps.”

“I think I can find my way to Devonshire,” he assured me. “If I get to Land’s End, I’ll know I’ve gone too far.”

Two (#ulink_e4f7948a-21d2-5d88-a65a-d9ebc13a24c2)

It was dark by the time we reached Sidmouth, and darker still by the time we turned off the main road to the small byway leading to the village of Abbots Burton. I had provided him with an imperfect address, but Sebastian had an excellent sense of direction and the wit to stop twice and ask the locals. A garage mechanic put him on the right road to carry us to the end of the village, and an avidly curious woman walking her Pomeranians pointed out the cottage.

“That’s it, Cowslip Cottage. There’s an artist that lives there,” she told him, edging around to get a proper look at me—the girl in the wedding dress sitting silently in the fancy motorcar.

Sebastian thanked the woman and nipped back into the vehicle, slamming the door sharply to put an end to the conversation. The woman tutted to her dogs as I smothered a laugh.

“Laugh now,” Sebastian told me dryly. “It will be all over the village by morning that your father has a visitor. If you wanted to keep your whereabouts a secret, I’m afraid you’d have been better off hiding out in London.”

I shrugged. Now that we were actually here the fight seemed to have gone out of me, and the look Sebastian gave me was decidedly worried.

“Damn, I’m a brute. I didn’t even think to feed you,” he muttered.

I smiled. “It doesn’t matter,” I assured him. “I couldn’t have eaten a bite.”

Just then my stomach rumbled loudly, as if to prove me a liar, and Sebastian grinned. “I’m sure your father will be more than happy to feed you up. Now, are you ready?”

I nodded, taking his hand as he helped me out of the motorcar. I’d come too far to turn back now, and I made a point of striding purposefully through the little gate at the front of the cottage and straight up to the door.

It wasn’t until I raised my hand to the knocker that I hesitated. But Sebastian was behind me, solid and reassuring, and I felt better for having him there. I suddenly realised I had never actually felt better for having Gerald around.

“I did the right thing in running away,” I murmured to myself. But still I did not knock.

“Allow me,” Sebastian said. He didn’t give me time to think. He simply lifted the knocker and dropped it into place with two sharp taps.

I barely had time to take a breath before the door opened. A man in a canvas apron stood on the threshold, scowling.

“What the devil do you want? Do you have any idea what time it is?” he barked.

I felt myself wilt, and Sebastian stepped forward, his expression livid.

“I say, that’s no way to talk to the young lady,” he began.

But before he could finish, the man in the apron was prodded aside by the business end of a walking stick. It was wielded by a tall gentleman with a head of thick silver hair and a primrose-striped smoking jacket. Father.

“Shut up, George. That isn’t how we welcome guests,” Father said. He came forward, rather slowly but with a very straight back. He peered at us and drew in his breath sharply.

“Poppy,” he breathed, and it sounded like a prayer. “Are you a mirage, child?” He put out his hand, a gnarled old hand with traces of rose madder across the knuckles. The skin on the hand was wrinkled and the fingers were twisted like the roots of an oak. An old hand, but still a graceful one.

I caught it in my own. “Yes, Father. It’s Poppy.”

He coughed hard, smothering what might have been an involuntary sound of emotion. He glanced sharply away, but when he looked back, he had recovered himself.

“Come in, child. You must be chilled to the bone. George, fetch tea and whisky. And sandwiches while you’re at it. I suspect our guests haven’t eaten,” he added.

He had not released my hand, and with it still grasped in his, he drew me into the sitting room of the cottage, where a bright fire burned upon the hearth. A pair of comfortable chairs had been arranged by the fire, but we did not sit.

“Father, I am sorry for just landing on you like this, and I will explain everything.”

“I already know,” he said mildly. “I get the newspapers even buried down here. You’re married.” He turned to Sebastian with a bland look. “I suppose I ought to offer you congratulations, young man. The heir to the Viscount Madderley, is it?”

I gave a strangled sound of horror, but Sebastian rose smoothly to the occasion. “I am afraid I do not have that honour, sir. I am Sebastian Cantrip.”

“Ah, yes. I see the dog collar now.”

I cut in before things could get entirely out of hand, muddling the introductions. “Mr. Cantrip, this is my father, Eglamour March, third son of the late Earl March, known to his friends and familiars as Plum. Father, Mr. Cantrip was the means by which I—that is to say—” I faltered, and turned pleading eyes to Sebastian.

He rose smoothly to the occasion. “Miss March, perhaps you would like to excuse yourself to wash your hands after the journey. I can explain matters to your father.”

Father gave Sebastian an assessing look, then flicked me a glance. “Back through the hall and up the stairs, my dear.”

I slipped out, hesitating outside the door. I could just hear them from my vantage point, Sebastian’s firm baritone underscored by Father’s rather more demanding aristocratic tone.

“Well, young man?” Father asked.

Sebastian hesitated, and I wished I could see their expressions.

“I’m afraid Miss March found herself disinclined to go through with the marriage. She was seeking a place of refuge,” he said solemnly. “I hope I have done right to bring her here.”

To my surprise, Father’s voice was tight with something that sounded like anger. “I suppose you didn’t think you had a choice.”

“No, I didn’t,” Sebastian countered, his own voice amused. “I daresay there will be a hue and cry and all sorts of bother before it’s all sorted, but these things can’t be helped.”

“What do you think you’re doing eavesdropping?” I jumped to find the manservant George lurking behind me, a laden tray in his hands.

“I dropped my handkerchief,” I lied coolly.

“I see no handkerchief,” he retorted.

“That’s because I haven’t found it yet,” I replied. I swept past him before he could make heads or tails of that answer, and fled up the stairs. I returned a few minutes later, face washed and hands clean, and smoothed out the crushed skirts of the wedding gown, wishing desperately that I had something—anything—else to put on.

“Next time I run away, I’ll plan better,” I muttered. I hurried into the sitting room to find Father and Sebastian sitting companionably. Food and drink had appeared in my absence but had not been touched. As soon as I took a chair the sandwiches and cakes were passed. I loaded my plate and dived in, scarcely breathing between bites. The sandwiches were dainty but stuffed with perfectly roasted ham, and the cake was light as a feather.

“George is quite something in the kitchen,” Father said, eyeing my rapidly emptying plate.

I swallowed and shot Sebastian a dark look as he helped himself to the last of the cherry tarts. The cherries had been brandied and glazed to look like jewels and the first two had melted in my mouth.

“He’s an interesting fellow,” I said politely.

Father arched a brow. “By that you mean he’s a boor, and you’re entirely correct. But he’s a devilishly good manservant and his company suits me. He frightens away all of the casual callers, and I am left to my work.”

His tone was light, but I felt the sting of loneliness in his words. I put my plate down, the cake suddenly ashes in my mouth.

“I don’t blame you,” he said softly.

I looked up into green eyes that were very like my own. Father was smiling. “It was your wretched mother’s doing. She’s the one I blame.”

A sharp blow sounded at the front door, and I started. Sebastian jumped to his feet, but Father sat serenely. “That will be the harpy now,” he said mildly.

“Most likely,” Sebastian agreed. “I drove fast, but I suspect they saw us getting away, and Mr. Hammond has a beauty of a Lagonda. I glimpsed it a few times on the road behind us.”

I threw Sebastian a horrified glance, and he stepped in front of me as if to act as my shield. From his seat, Father gave us a curious glance and was watching us still when George appeared.

“Shall I answer that, sir, or send them to Coventry?”

“By all means, answer it,” Father said, waving an airy hand. “Might as well get it done with now. I have too much experience of Araminta’s temper to think it will sweeten by morning.”

I rose to my feet, my hand sliding neatly into Sebastian’s. At the warm touch of his skin, I jumped, pulling free and thrusting both of my hands behind my back. All proper behaviour seemed to have flown out of my head, and I found myself wishing I could faint or fall into a fit, anything to avoid the next few minutes.

“She’ll be frightfully angry,” I warned Sebastian. “This is far worse than the time I kept a pet frog in the bidet at the Ritz.”

“Courage,” Sebastian murmured.

I nodded and took a deep breath as George returned. “Mr. and Mrs. Hammond, sir. And I didn’t get the names of all the rest of them. There were too many,” he added nastily. He stepped aside to let Mother and Reginald into the room, and behind them came an avalanche of people.

“Good God,” Father pronounced. “Am I to be invaded by a whole tribe of Americans?”

“It’s just the family,” I assured him. “That’s my stepfather, Mr. Hammond, and of course, you know Mother, and those are the twins, Petunia and Pansy, and I think those must be the boys back there, Reginald Junior and Stephen. There’s my maid, Masterman—she’s the one looking disapproving. And oh, yes, there’s Gerald. Hello, Gerald,” I said as calmly as I could manage. “You haven’t met my father, Eglamour March. Father, Gerald Madderley.”

Father took a deep breath and rose slowly from his chair. He greeted Gerald, then put out his hand to my stepfather. “How do you do, Mr. Hammond. I believe we have something in common,” he said, his voice acid on the last word as he glanced at Mother.

She was not pleased. Her tone was just as cold as his as she watched her two husbands shake hands. “Yes, let’s all be marvelously polite about this, shall we? In the meanwhile—”

“In the meanwhile, Araminta, you’ve had entirely too many children for my sitting room to accommodate,” Father said firmly. “Now, those boys will have to go as well as the girls with the appalling flower names. Madderley, I suppose you have a dog in this fight, so you may stay. Hammond, since you paid for the affair, you are welcome to stay, as well. And let’s have the maid in case anyone decides to succumb to the vapours. Araminta, you will stay only so long as you can keep a civil tongue in your head.”

Mother opened her mouth to reply then snapped it closed. “Very well,” she said through gritted teeth. “Children, out to the car. And mind you don’t get out and go walking about. These English villages are full of typhoid. They have very bad drains.”

Father gave a short laugh. “Good God, how could I have forgot your obsession with drains?”

“I think we have more important matters to discuss,” she told him, her voice icy. She turned to me. “Poppy, do you have anything to say for yourself?”

I looked from my enraged mother to Gerald’s mild face and back again. “Only that I am very sorry for behaving quite so badly. I ought to have said something sooner—”

“Sooner!” Mother’s voice rose on a shriek. “You mean, you knew? You knew you had no intention of marrying Gerald and you let this all play out like some sort of Elizabethan tragedy—”

“Oh, for God’s sake, Araminta, a pair of people who probably weren’t terribly suited didn’t get married. I would hardly call that a tragedy,” Father put in.

“Of course you wouldn’t,” she replied. “You are the very last person who would understand about keeping one’s sacred promises.”

He raised a silver brow. “A hit. A palpable hit,” he said, his tone amused. “I was waiting for that, and I’m so glad you didn’t disappoint.” He turned to Reginald with an appraising gaze. “You must have the patience of Job, good sir. I salute you.” He raised a glass of whisky in Reginald’s direction.

“I play a good bit of golf,” my stepfather told him. “It teaches patience like nothing else.”

Mother opened her mouth, no doubt to blast Father again, but she suddenly seemed to catch sight of Sebastian. “Who are you? I recognise you. You were at the church today. Do you mean to say—” She broke off, her expression one of mounting horror. “Oh, my dear God. I cannot believe it. Not even you, Penelope, would be heartless enough to elope on your wedding day with another man.”

Sebastian opened his mouth, but before he could get out a word, Gerald stepped up and clipped him under the chin with one good punch, snapping his head back smartly. Sebastian kept his feet for a moment, then his eyes rolled back into his head and he slid slowly to the floor.

Gerald stood over him, shaking out his hand while Father called for George to bring cold cloths, and the children, hearing the uproar, dashed in from outside. As they crowded into the sitting room, Reginald attempted to calm Mother as she hysterically berated me while I stared in horror at Sebastian’s closed eyes.

Father threw up his hands. “It seems we must surrender to pandemonium,” he said to no one.

George brought the cloths as I shoved Gerald out of the way to kneel over Sebastian. Father guided Gerald to the fire and gave him a glass of whisky while I held a cold, wet cloth to Sebastian’s jaw. His eyes fluttered open, wide and very dark. I leaned over him, one hand on his chest, and he reached up to clasp my hand as my face hovered inches from his.

“Can you hear me?” I pleaded. “Are you all right?”

His mouth curved into a smile.

“Lovely,” he murmured. “Just a bit closer.”

I gasped. “You fraud!” I muttered just loudly enough for him to hear. “He didn’t knock you out at all.”

Sebastian rolled his eyes. “No, but I wasn’t about to give him the chance to try again. This way he keeps his pride, and I don’t make a mess of your father’s sitting room carpet by shedding Madderley blood all over it.”

I pushed off his chest, sitting upright and handing him the cloth. “You can hold your own compress,” I told him tartly. I didn’t even bother to explain to him that Gerald had been the boxing champion of his year at Harrow. There was something rather endearing about Sebastian’s faith that he could trounce Gerald, and I had learned enough about men to let him keep his illusions, although I had to admit the chest under my palm had been very firmly muscled.

A quarter of an hour later, order had been restored. Sebastian was sitting upright in one of the chairs, nursing a large whisky and making a show of holding a cold compress to his jaw. Mother had ordered the younger children to return to the motorcar, which they did under violent protest, and Father had opened a bottle of his best single malt to share with Reginald—a sort of reward for the job he had done soothing Mother’s hysteria. Masterman the maid simply stood out of the fray, her expression inscrutable as a Buddha as she watched the chaos unfold.

I sipped at my own whisky as Mother regarded me coldly.

“I do not approve of young ladies drinking spirits,” she said.

“Considering the circumstances, it’s a wonder she isn’t sniffing cocaine,” Father put in. He poured another measure for an appreciative Reginald and settled himself back into his chair.

“Now, I think we can all agree that physical violence is not called for under the circumstances and that we ought to discuss matters like adults,” Father began with a dark look to where Gerald sat nursing his sore knuckles in the corner. Gerald flushed but said nothing.

“Too bloody late for that,” Sebastian muttered.

“Yes, well,” Father said, trailing off with a vague smile. “Now, I think it is quite clear that Poppy did not in fact elope with Mr. Cantrip. He obviously thought he was carrying out some act of chivalry, for which his only payment has been a rather lucky blow from Mr. Madderley.”

Sebastian glowered at Gerald, who studied the carpet with rapt fascination.

Father went on. “Now, there are many things to be settled, but the first is one of the law. Mr. Cantrip, you are entitled to bring charges against Mr. Madderley for the assault to which we have all been witness. Do you wish me to send for the police so that you may do so?”

There were shocked gasps from around the room, but Gerald lifted his chin, ready to do his duty manfully.

All eyes were fixed on Sebastian. “God, no,” he moaned.

“Very well,” Father said, his expression one of grudging admiration. “Now, Poppy, your former fiancé has travelled down here, clearly with an eye to carrying you back to London and into the bonds of holy wedlock. Do you wish to go with him?”

“God, no,” I said, echoing Sebastian as I dropped my head into my hands.

“Very well. Mr. Madderley, you are excused.”

Gerald bolted to his feet. “Now, see here—”

“No,” Father said pleasantly. “I don’t have to see anything. What you must see is that you have intruded upon the peace and tranquility of my house by bringing violence into it. The young man you assaulted is good enough to overlook your bullying, and my daughter wishes to have nothing to do with you. Therefore, you have no further business here. Go away. And next time, choose a girl who actually loves you. My daughter clearly does not.”

I raised my head to watch as Gerald opened his mouth a few times, but no words came. He turned wordlessly on his heel and left.

Father gave me an appraising look. “If that’s the sort of man you chose of your own free will, your mother has done a far more tragic job of bringing you up than I would have credited.”

“Oh, that is like you, Eglamour,” Mother began.

Father lifted an elegant hand. “I’m sure you did your best, Araminta. But it is quite clear that you’ve raised a daughter who has absolutely no idea how to speak to you, otherwise she would have told you ages ago she had doubts about this wedding.”

Mother’s eyes narrowed. “How do you know she had doubts about this wedding?”

Father’s look to me was kindly. “Because she went to the trouble to find out my address some weeks back. I’m sorry, child, but your Aunt Portia has never been particularly good at keeping secrets. She told me you asked for my address, and I hoped you would come to me if you needed me.”

“Thank you, Father,” I said, almost inaudibly.

“Now, I know you want to abuse her further, Araminta, and I won’t say she hasn’t acted quite badly. I’m sure you, Mr. Hammond, are out quite a few of your American dollars on this wedding that almost was,” Father said.

Reginald looked uncomfortable as he always did where money was concerned. “Well, if it made her happy,” he said, trailing off.

“Yes, well, I think we can all agree it did not make her happy. In fact, I daresay the child doesn’t know what will. But she needs rest and time to discover that.”

Mother gathered up her resolve and opened her mouth, but Father lifted his hand again.

“No, Minty. I will give you full credit for raising a lovely girl. She’s audacious and brave and passably clever, I’d say, and, like all Americans, beautifully groomed. But she’s also limp with exhaustion, and a scene with you is the last thing she needs. Leave her here with me. For one month. At the end of that time, I will deliver her to London myself to face the consequences of her actions.”

The fight seemed suddenly to go out of Mother and I stared, rapt. I had never known anyone, not even Reginald, to handle her so deftly. I could see him paying close attention—I only hoped he was taking notes. Mother sniffled a little, capitulating under Father’s masterful handling. “I don’t know what to do with her, Plum. I never did. She’s exhausting, always asking questions and never satisfied just to be. There’s always something new she wants to do, some new scheme to try. Cookery classes and psychology courses and driving lessons, and none of them ever finished. It’s one mad idea after another and so much...she’s just so...so March.”

Father smiled thinly. “Blood will out, dear Minty. Now, go back to London with your appallingly healthy and boisterous brood of Americans and let me sort this out. Perhaps you could send down some clothes for her if you think about it. She can’t totter about like Miss Havisham in her wedding finery.”

Mother rose. “Naturally, I’ve already thought of that. Her trousseau trunk is in the car.” She turned to my maid. “Masterman, we cannot expect you to continue in service with Miss Hammond after today’s debacle. We will naturally give you an excellent reference, a month’s wages, and a ride back to London. It was good of you to come this far.”

Masterman stirred. “On the contrary, madam, I should like to remain with Miss Hammond.”

Mother blinked. “Whatever for?”

Masterman’s expression did not change, but I had the strangest feeling Mother might have more easily shifted the Pyramids than moved Masterman from her decision. “Because it suits me, madam,” she replied quietly.

Mother shrugged. “Very well, but do not be surprised if you find you can’t stick it after all. Miss Hammond can be extremely trying to one’s nerves.” Mother turned and gave me a long look. “One month, Penelope. You have one month to figure out what it is that you want. This is the last time I will clear up a mess you’ve left behind.”

She turned on her heel and swept from the room. Reginald stepped forward, putting a kindly hand on my shoulder as I stared after her in dismay.

“Don’t fret, honey. I’ll settle her down. You just rest and don’t worry about anything. And I’ll put some money into your account,” he added softly. Dear Reginald, always solving everyone’s problems by throwing cash at them.

I summoned a smile and rose on tiptoe to press a kiss to his smoothly shaven cheek. “You really are a very nice man, Reginald.”

He ducked his head and shook hands with Father before following Mother out the door. Father sat back in his chair with an air of satisfaction.

“That man ought to be sainted,” he mused. “For miraculous fortitude.”

“Mother isn’t so bad,” I began automatically.

“She’s a nightmare,” Sebastian observed in a dry voice.

“Dear God, I almost forgot you were still here,” Father said, perking up. “It’s grown late. I suppose we shall have to offer you a place to sleep tonight. George can show you over to the inn. They’ve always a room in reserve for one of my guests, and they’ll be happy to accommodate you. As for you—Masterman, was it? There is an extra bed in the guest room upstairs. Help your mistress, there’s a good girl. I think Poppy is half-asleep on her feet.”

I started to protest that I could very easily make my own way upstairs, but Masterman had taken charge of the situation. I didn’t know if she was more put out at having to share a room or Father calling her a girl, but she pushed me firmly up the stairs and put me to bed with ruthless efficiency. I gave myself up to it, letting her bully me a little since it suited us both. She turned out the light and undressed swiftly, settling herself into the narrow extra bed.

“You didn’t have to stay on,” I told her sulkily. There had been a certain guilty glee in ridding myself of Gerald, but it was a little blunted with Masterman still there to make certain I didn’t do anything interesting.

“Yes, I did,” she said, her voice almost fierce in the darkness.

“But why?”

“My reasons belong to me, miss. Now go to sleep or you’ll look a fright in the morning,” she said.

So I did.

Three (#ulink_6aa9d853-15c9-553e-840b-c40956da8462)

The next morning Masterman busied herself unpacking my trunk while I found Father at breakfast. I murmured a greeting and slid into a chair, smiling widely at a glowering George who banged a pot of tea on the table in front of me and trudged off for a fresh rack of toast.

“Poor soul,” I said quietly. “I imagine he was in the war. Is it shell shock?”

Father lowered his newspaper and gave me a thoughtful look. “You mean his foul moods? No, no. George is a flat-footed Quaker, entirely unsuited to the soldiering life. He’s just churlish. But he is an excellent cook and I’ve never had whiter linen,” he finished. He went on looking at me intently.

“I behaved very badly, didn’t I? It all seemed so remote yesterday, as though it were happening to a stranger, but today...” I trailed off.

“Today it is news,” Father said, passing the newspaper.

There it was, in black and white for all to see. Viscount’s Heir Jilted By American Society Girl. I shook my head. “How awful it sounds. And I’m not really American,” I protested.

Father smiled. “Thank God for small mercies. At least you sound like one of us. It’s been quite a few years since I’ve seen you. You have a look of the Marches about you. Puts me quite in mind of your Aunt Julia when she was your age, although your hair is fairer.”

“If it weren’t for my aunts, I wouldn’t be in this frightful mess,” I said darkly.

Father raised his brows inquiringly, and before I knew quite what I was saying, the entire story tumbled out, starting with Aunt Portia’s gift of Married Love. I paused only while George brought in the toast, but as soon as he returned to the kitchen, I carried on.

“And that’s it, minus the gruesome details,” I added. I alluded to a fundamental incompatibility with Gerald, but there had been no actual mention of sex-tides. Some things a girl cannot share with even the most liberal of fathers. I gave him a smile. “You’ve been truly marvellous, and I know it can’t have been easy, not with Mother descending like all the plagues of Egypt yesterday.”

Father smiled again. “I can cope with Araminta. And I must say, I’m very glad you felt you could come to me. I know I’m little more than a stranger to you really.”

“But you aren’t,” I protested. “I had your letters. At least Mother let us correspond. And I always think letters are terribly intimate, don’t you? I mean, you can tell the page things you can’t ever say to a person’s face.”

“Heart’s blood in place of ink?” he asked, his eyes bright.

“Precisely. Although I seem to be doing a rather good job of telling you what I’m thinking now. I probably shouldn’t have told you any of it, but it seems that once I told it all to Mr. Cantrip yesterday, I can’t stop talking about it. Very freeing, I find.” I plucked a fresh piece of toast from the rack and buttered it liberally. “Of course, now I have to decide what to do with myself.”

“Surely that won’t be difficult.”

“Not for a person like you,” I said, nodding to the exquisite framed landscapes on the walls. “You’ve always had your painting. I’m simply hopeless. I was expensively educated to be decorative and charming and precious little else. Mother was right, you know. I never stick with anything because I don’t seem to be good at anything.”

“What have you tried?”

I shrugged. “All the usual nonsense they make you do at school, at least at schools for young ladies. Flower arranging, painting, music.”

“And none of those suit you?”

“My flower arrangements look like compost heaps, my paintings all look like bogs, and as for music, I have the keenest appreciation for it and no ability whatsoever to understand it. I think it’s because of the maths.”

“Maths?”

“Music is all mathematical, at least that’s what our music master told us. And I was frightful at maths, as well.”

“Rather a good thing your Uncle Lysander isn’t alive to hear you say it. He was a gifted composer, you know. You would have crushed him thoroughly.”

I gave him a sympathetic look. “I know I wrote at the time, but I really am quite sorry. I should have liked to have known him. Perhaps I can meet Aunt Violante and the children whilst I’m here.”

Father stared into the depths of his teacup as if looking for answers. He said nothing, and I moved on, my tone deliberately bright. “In any event, I’m hopeless at all the usual female things. All I seem to be good at is poking around into people’s lives. Headmistress used to say I could take a First in Gossip if it were on offer at Oxford.”

A ghost of a smile touched Father’s lips. “Your Aunt Julia is precisely the same. I sometimes wonder if Mr. Kipling met her somewhere and used her as the basis for his inquisitive mongoose. ‘Go and find out’ will be etched on her gravestone. But she has ended up doing well enough for herself.”

I rolled my eyes. “I should say. It is rather grand having a duchess in the family since I threw away my chance at being a peeress.”

“Believe me, child, being a duchess is the least of her accomplishments, and it was entirely unexpected. If it weren’t for peculiar Scottish peerage laws and half a dozen young men getting blown up in the war, her husband would never have succeeded to the dukedom. No, I wasn’t thinking of her rank, child. I was thinking of her work. She struggled with many of the same feelings you have. She found purpose in joining her husband’s work. I know it’s practically revolutionary to suggest it, but I don’t think idleness is good for young people—particularly not young people with money. It grinds away at the character until there’s nothing left.”

I tipped my head, thoughtful. “You think I ought to take a job? Like something in a shop?”

He smiled again. “I doubt a shopkeeper would want you if you’re hopeless at maths. I was thinking of something that excited you, stirred your sense of adventure. You need to be challenged, child. You need to see something of the world, and from some vantage point other than your stepfather’s yacht. Oh, I’ve seen the society columns,” he went on. “I know what it means to be the stepdaughter of a man like Reginald Hammond. You think you’ve seen the world because you’ve been to New York and Paris and Biarritz, but what have you really seen other than a pack of useless people exactly the same as the ones you left behind? Same old faces, same old places,” he pronounced.

I nodded. “You’re right, of course. There are times I want to simply scream with boredom. But I wouldn’t even know where to start to look for something useful to do.” My glance fell to the newspaper, and I grinned as I pointed to an article. “How about this? Apparently the famous aviatrix Evangeline Starke has disappeared in the Syrian desert. Perhaps I should give flying lessons a bash,” I added.

Father lifted an elegant brow. “I was thinking of something a trifle less life-threatening.”

I was about to suggest rally-car driving when George appeared in the doorway. “It’s that Mr. Cantrip,” he said darkly.

Father smoothed his turquoise waistcoat. “Very well. Send him through, George.”

I was still immersed in the article about Evangeline Merryweather Starke when Sebastian entered and Father greeted him coolly.

“Good morning, Mr. Cantrip. I trust you had a good night’s sleep at the inn?”

“Very good, thanks. Good morning, Miss March.” The name took me aback for a moment then I grinned to myself. I had played at being Miss Hammond for too long. It was time to reclaim my own name once and for all.

I looked up and flashed him a quick smile. “Good morning.” My face fell as I took a closer look at him. A spectacular bruise was blossoming on his jaw, and I jumped to my feet.

“Oh, heavens! It’s worse than I thought last night. I still can’t quite believe Gerald did that to you. He’s always seemed so mild-mannered.”

Sebastian touched his jaw ruefully. “Yes, well, apparently still waters run deep in his case.” He glanced down at the newspaper on the table. “I see you’ve the morning edition there. I suppose they’ve been rude about you?”

I pulled a face. “Brutal. As expected. One doesn’t just jilt a peer’s son with impunity,” I said with an attempt at lightness. “But I’m far more interested in this story about the aviatrix who’s gone missing in Syria.”

I handed the newspaper to Sebastian, who skimmed the article quickly. He gave it back without a word and I looked at him curiously. “Are you quite all right, Mr. Cantrip? You’ve gone very white under that bruise.”

Sebastian summoned a smile that didn’t quite meet his eyes. “Have I? I suppose it’s just the delayed effects of yesterday’s dramatics. Shock and all that. I’ll be right as rain in a bit.”

“Won’t you have some breakfast?” Father asked him, his expression thoughtful.

“No, sir, thank you. They fed me quite heartily at the inn. I merely wanted to pay my respects on my way back to London.”

“You’re going back? Already?” I masked the pang I felt with a quick smile. “Of course you are. You have a parish there, and I’ve managed to drag you away from it and through the muck. Shall I see you out?”

He followed me to the front door of the cottage.

“I know what you’re worried about,” I said, pitching my voice low. “But you aren’t named in the newspaper piece,” I assured him. “They haven’t any idea how I got away, and I won’t tell a soul. I ought to have realised what awful trouble you could get into by helping me, and I won’t forget it. Really, I owe you most dreadfully and I never forget a debt.”

He shook his head, his expression dazed. “You are a unique young woman, Miss March.” He hesitated on the doorstep. “I wish I didn’t have to dash away.”

“So do I,” I told him. “I feel as if I’ve just imposed on you horribly and haven’t had the chance to make it up to you.”

For an instant the buccaneer flash was back in his eyes, and I wondered just how hard he found it to be a properly behaved member of the clergy. “Would you like to make it up to me?”

I felt a thrill at his audacity, but I primmed my mouth, remembering propriety for once.

“Thank you. For everything.” I put out my hand, but he ignored it. Instead he settled both of his hands on my shoulders, leaning down to brush a quick kiss to my cheek. He hadn’t shaved, and his whiskers rasped a little against my skin. Before I could respond, he was gone, out the door and out of my life as quickly as he’d come.

I closed the door behind him feeling a little deflated and oddly nostalgic. He had been a perfect companion in my little adventure, and I could never have managed my escape without him. After months of Gerald’s chilly affections, being around Sebastian had been like basking in summer sunshine. It was absurd, I told myself firmly. I had only just met him. One couldn’t get homesick for a person.

When I returned to the breakfast table, Father was looking thoughtfully at the newspaper I’d left behind.

“Everything all right, Father?”

He gave me a bland smile. “Quite, my dear. Now, finish your breakfast and perhaps you and Masterman would like to take a nice walk and get acquainted with the village. This will be your home for as long as you like.”

* * *

It took fewer than twenty minutes to walk completely around the village, and by the time I finished I had a pebble in my shoe and had counted precisely seventeen front curtains twitch as we walked past.

“It seems the entire village has already heard about our arrival,” I told Masterman.

She pursed her lips. “People are the same wherever you go, miss—interested in gossip and scandal, and you’ve given them meat enough to feed on for a year.”

We had just come to the pond on the village green and I stopped. I had been considering how to approach her ever since she had told Mother she would stay with me. It wasn’t that I didn’t like Masterman, not exactly. But she was my last tie to Gerald’s family and my near-miss as the future Viscountess Madderley. The sooner I severed that connection, the better. Besides, there was something uncanny about her, a quiet watchfulness I didn’t entirely understand.

I cleared my throat. “It’s really very good of you to stay on, all things considered.” I chose my words carefully. “After all, working for me won’t exactly count in your favour when you apply for a new position.”

She said nothing as we walked on, and I decided to push just a little further. “I mean, you won’t want to go on working for me forever. I don’t even know what my plans will be.”

“I am certain you will figure it out,” she said mildly.

I suppressed a sigh. She was going to be difficult to dislodge, I decided. And the only solution was a more direct approach.

“See here, Masterman—”

She turned to look at me, her hazel eyes placid. There was a slightly greenish cast to them, like a mossy stone on a riverbed. “I am not leaving, miss.”

I gaped at her. “How on earth did you know that’s what I was about to suggest?”

She shrugged. “It’s only logical. Mrs. Hammond suggested it last night and you lit up like Bonfire Night.”

I ducked my head. “That wasn’t very kind of me. I apologise, Masterman. And it isn’t that I don’t like you. You mustn’t think that.”

“I don’t,” she replied with that same unflappable calm.

“Oh, well, good. Because I do,” I assured her with a fatuous smile. “It’s just that—”

“I make you uncomfortable,” she supplied.

“That’s not at all what I meant to say,” I said, feeling my cheeks flush warmly.

“But it is what you feel,” she said. There was no malice in her voice and her gaze was calm and level. I heaved a sigh.

“Very well. Yes. You make me uncomfortable. I’m afraid you’ll always be a reminder of how badly I behaved.”

“But I don’t think you did behave badly,” she told me.

I stared at her a long moment. “That might be the nicest thing you’ve ever said to me.”

“It happens to be true,” she said. She began to walk and I hurried after, suddenly eager to talk to her. There was something curiously topsy-turvy about the mistress chasing after the maid, and I grinned as I caught up to her.

“You don’t think I ought to have married Gerald?”

“Absolutely not. Miss March, what do you think a servant’s chief responsibility is?”

I thought of the endless round of brushing clothes and whipping hems and pinning hair and shrugged.

“It’s to be watchful—to see all and understand what we see. I watched you with Mr. Madderley, and I could tell from the first moment I saw you together you were entirely unsuited.”

“You might have told me,” I said, kicking a pebble.

“You did not ask,” she returned mildly.

I grinned again. “All right, Masterman. I’ll give you that. And you can stay on if you like.”

She gave me a brisk nod to indicate her acceptance. We walked on in silence for a little while, taking a turn around the pond. A few apathetic ducks bobbed on the glassy surface and a limp lily floated along. There was no one else on the village green, and even the smoke coming from the chimneys drifted in lazy circles.

“Masterman, with your gift for watchfulness what do you make of our present circumstances?”

She looked around the village, taking in the quiet shops and tranquil, sleepy air of the place.

“I think, miss, we are in very great danger of being bored.”

* * *

She was not wrong. After that, our days settled into a pattern. Masterman and I went for long walks each morning, and after luncheon Father painted in his studio while I tried to make friends with George, although he remained stubbornly unmoved by my charms. I asked him to teach me to make his clever little soufflés or roast a duck or let me polish the silver, but each attempt was met with a firm rebuff. “That’s your side of the cottage,” he would state flatly, pushing me out of the kitchen and back into the hall. It was too bad really, because I was bored senseless and genuinely interested in acquiring a few new skills. It might come in handy to be able to roast a duck, I thought, but George was unwilling to oblige.

So I occupied myself with brooding. I wrote no letters and received only one—a curt message from Mother stating that she had returned the wedding gifts but that I had been remiss in returning my engagement ring to Gerald. It was an enormous pigeon’s blood ruby, a relic from the days of the first King George and worn by every Madderley bride. The viscountess had been particularly resentful at giving it up, and I was abashed I hadn’t thought to give it back to Gerald when he left the cottage. I made a note to take it with me when I went up to London next; I couldn’t possibly trust such a valuable jewel to the post. But London held no charms for me in my present mood. I had given up reading the Town newspapers after the second day. They were vitriolic on the subject of my almost-marriage, and going up would mean facing people who had decided I was only slightly less awful than Messalina.

So I buried myself in books, raiding Father’s library for anything that looked promising. There were a handful of Scarlet Pimpernel books and an assortment of detective stories, but beyond that nothing but weighty tomes on art history. I had almost resigned myself to reading one of them when I discovered a set of books high on a shelf, bound in scarlet morocco. They were privately printed, that much was obvious, and I gave a little gasp when I saw the author’s name: Lady Julia Brisbane. She was Father’s youngest sister, and the most notorious of our eccentric family. After a particularly awful first marriage, she had taken as her second husband a Scot who was half-Gypsy and rumoured to have the second sight. The fact that he was distantly related to the Duke of Aberdour hadn’t counted for much, I seemed to recall. There had been scandal and outrage that a peer’s daughter had married a man in trade. Nicholas Brisbane was a private inquiry agent, and Aunt Julia had joined him in his work. Ending up a duchess must have been particularly sweet for her, I decided. Father had talked about them my first morning at the cottage, and as near as I could guess, these books were her memoirs.

I turned the first over in my hands. Silent in the Grave was incised in gilt letters and a slender piece of striped silk served as a bookmark. I opened to the first page and read the first line. “To say that I met Nicholas Brisbane over my husband’s dead body is not entirely accurate. Edward, it should be noted, was still twitching upon the floor.” I slipped down to sit on the carpet, the books tumbled in my lap, and began to read.

I did not move until it was time for tea, and only then because Father joined me. He beckoned me to the table by the fire, giving a nod of his silvery-white head to the book in my hands.

“I see you’ve discovered Julia’s memoirs.”

I shook my head, clearing out the cobwebs. I had spent the whole day wandering the fog-bound streets of Victorian London with my aunt, striding over windy Yorkshire moors and climbing the foothills of the Himalayas. I took a plate from him and sipped at my tea.

“I can’t believe I never knew she did all those things.”

His smile was gentle. “It’s never been a secret.”

“Yes, I always knew she went sleuthing with Uncle Brisbane but I had no idea the dangers they faced. And you—”

I broke off, giving him a hard look.

He burst out laughing. “There’s no need to look so accusing, child. Yes, I did my fair share of detective work, as well.”

“I can’t believe Aunt Julia almost killed you once with her experiments with explosives.”

“Once?” His eyes were wide. “Keep reading.”

He urged sandwiches and cakes on me, and I ate heartily, suddenly ravenous after missing luncheon entirely.

“That’s what I want,” I told him.

He had been staring into the fire, wool-gathering, and my voice roused him. He blinked a few times and looked up from the fire. “What, child?”

“I want what Aunt Julia has. I want a purpose. I want work that makes me feel useful. I don’t just want to arrange flowers and bring up babies. Oh, that’s all right for other girls, but it isn’t right for me. I want something different.”

“Perhaps you always have,” he offered mildly.

“I think I have,” I replied slowly. “I’ve always been so different from the others and I never understood why. My half-sisters and -brothers, my schoolmates. Don’t mistake me—I’ve had jolly enough times, and I’ve had friends,” I told him, pulling a face. “I was even head girl one year. But as long as I can remember, I’ve had the oddest sense that it was just so much play-acting, that it wasn’t my real life at all. Does that sound mad?”

“Mad as a March hare,” he said, his lips twitching. He nodded to the mantelpiece, where a painting hung, a family crest. Our family crest. It was a grand-looking affair with plenty of scarlet and gold and a pair of rabbits to hold it up. “Family lore maintains the old saying about March hares is down to us, that it isn’t about rabbits at all. It refers to our eccentricity, the wildness in our blood. And the saying is a tribute to the fact that we do as we dare. As do you,” he finished mildly.

I started. “What do you mean by that?”

A wry smile played over his lips. “I know more of your exploits than you think, child.”

“Exploits! I haven’t done anything so very interesting,” I protested.

He gave me a sceptical look. “Poppy, give me some credit. I mayn’t have been a very devoted father, but neither have I been a disinterested one. Every school you’ve been to, every holiday you’ve taken, I’ve had reports.”

“What sort of reports?” I demanded.

“The sort any father would want. I had little opportunity to ascertain your character myself, so I made my own inquiries. I learnt you were healthy and being brought up quite properly, if dully. Araminta has proven herself a thoroughly unimaginative but unobjectionable mother. At first, I thought it best, given the sort of family we come from. I thought a chance at normality might be the best thing for you. But the more I came to discover of you, the more I came to believe you were one of us. They do say that blood will always tell, Poppy.”

I gave him a look of grudging admiration. “I’m torn. I don’t know whether to be outraged that you spied upon me or flattered that you cared enough to do it.”

His smile was wistful. “I always cared, child. I cared enough to give you a chance at an ordinary life. And if you think that wasn’t a sacrifice of my own heart’s blood, then you’re not half as clever as I think you are.”

His eyes were oddly bright and I looked away for a moment. I looked back when he had cleared his throat and recovered himself. “I’m surprised you found me clever from my school reports. The mistresses were far more eloquent on the subject of my behaviour.”

“No, your marks were frightful except in languages. Looking solely at those I might have been forgiven for thinking you were slightly backwards. It was those reports of your behaviour that intrigued me, particularly the modest acts of theft and arson.”

“But those were necessary!” I protested. “I broke into the science master’s room to free the rabbits he’d bought for dissection. And the fire was only a very small one. I knew if the music mistress saw her desk on fire, she’d reveal where she’d hidden the money they accused the kitchen maid of stealing.”