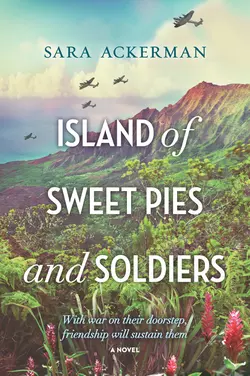

Island Of Sweet Pies And Soldiers: A powerful story of loss and love

Sara Ackerman

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 305.03 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Hawaii, 1944. The Pacific battles of World War II continue to threaten American soil, and on the home front, the bonds of friendship and the strength of love are tested.Violet Iverson and her young daughter, Ella, are piecing their lives together one year after the disappearance of her husband. As rumors swirl and questions about his loyalties surface, Violet believes Ella knows something. But Ella is stubbornly silent. Something—or someone—has scared her. And with the island overrun by troops training for a secret mission, tension and suspicion between neighbors is rising.Violet bands together with her close friends to get through the difficult days. To support themselves, they open a pie stand near the military base, offering the soldiers a little homemade comfort. Try as she might, Violet can’t ignore her attraction to the brash marine who comes to her aid when the women are accused of spying. Desperate to discover the truth behind what happened to her husband, while keeping her friends and daughter safe, Violet is torn by guilt, fear and longing as she faces losing everything. Again.Readers love Ackerman:“a well written novel, well researched and well told”“A book that I could hardly put down, I highly recommend it, this is a 5 star novel”“This book was a joy to read, due to the rich and interesting characters”“charming, engaging read”“A beautifully written story by an exciting new author”“ I loved the book!”“a heartwarming story of friendship and survival”“After reading this book, I want to read more historical fiction”