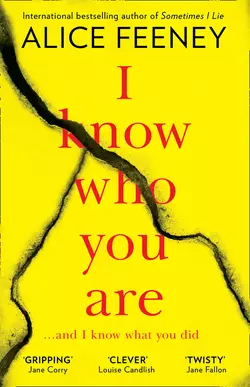

I Know Who You Are

Alice Feeney

Praise for Alice Feeney:‘Marvellous’ A. J. Finn‘A bold and original voice’ Clare MackintoshAimee Sinclair: the actress everyone thinks they know but can’t remember where from.Except me. I know exactly where you’re from, who you are, what you’ve done.Your husband has gone missing and the police think you’re hiding something. You lie for a living, always pretending to be someone else. But that’s not new, is it?Because I know you lied before. You’ve always lied. And the lies we tell ourselves are always the most dangerous . . .This twisty new psychological thriller will leave your heart pounding and your pulse racing. From the bestselling author of Sometimes I Lie, this is a brilliantly told and expertly crafted novel you won’t be able to put down.

ALICE FEENEY is a writer and journalist. She spent fifteen years at the BBC where she worked as a reporter, news editor, arts and entertainment producer and One O’clock news producer.

Alice has lived in London and Sydney and has now settled in the Surrey countryside, where she lives with her husband and dog.

Her debut novel, Sometimes I Lie, was a New York Times and international bestseller. The book has been sold in over twenty countries and is being made into a TV series by a major film studio. I Know Who You Are is her second novel.

Copyright (#ulink_83535f57-d9fd-5e11-b499-3742a5785a7a)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Diggi Books Ltd

Alice Feeney asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008236083

More praise for Alice Feeney:

‘Boldly plotted, tightly knotted – a provocative true-or-false thriller that deepens and darkens to its ink-black finale. Marvellous.’

A J Finn

‘A bold and original voice – I loved this book.’

Clare Mackintosh

‘Expect perfectly imbedded twists and sharply drawn characters. A brilliant thriller.’

Ali Land

‘A gripping debut with a brilliant twist, I loved it.’

B A Paris

‘A tightly written thriller with an ending that demands you go straight back to the beginning.’

Metro

‘Satisfyingly serpentine, and with a terrific double twist in the tale, it leaves you longing for more.’

Daily Mail

‘Intriguing, original and addictive, I can’t wait to see what the author does after this blinding debut.’

The Sun

‘Clever, compelling and masterfully plotted.’

Daily Express

‘Sometimes I Lie is a rare book, combining helter skelter twists with razor sharp sentences. Make sure you read it in a well lit room, Alice Feeney’s imagination is a very dark place indeed.’

Dan Dalton, BuzzFeed

‘This is a thriller that grabs you and holds you in its thrall.’

Nicholas Searle

For Jonny.

Agents come in all shapes and sizes.

I got the best.

Not everybody wants to be somebody.

Some people just want to be somebody else.

Contents

Cover (#ue0e402cb-b7c5-504f-a7e2-497cb8e93b49)

About the Author (#u9e924ae7-86b4-54ea-bee0-07c3257b2478)

Title Page (#u2b9b98e3-28f9-5d0c-84a8-2e85582c79a1)

Copyright (#ulink_e4d4b12b-4629-588d-bd2b-1f9d22d83371)

Praise (#ulink_d689cd67-ff69-5394-be6e-2ec54ecaace4)

Dedication (#u0c8bc4a1-e788-5a37-8bd4-95ae91d98aee)

One (#ulink_b84caa28-0b83-5acf-8cf9-32e4bb1664f6)

Two (#ulink_4aec53e0-56b5-577f-bd0d-b5d7020ac6f9)

Three (#ulink_83947721-b919-565f-8002-6f695df92592)

Four (#ulink_2b1c650b-756e-5406-9b10-8c405d17ed79)

Five (#ulink_e4008ea1-4bc6-5e63-a7fb-f42f18e96fb6)

Six (#ulink_2d91b7d1-7541-5bd3-a2b3-54379126f8d0)

Seven (#ulink_acdf9ede-4758-5559-b5ee-5f996ed5a3d6)

Eight (#ulink_e2e913f5-ab12-5d53-98a4-338cce0e6bbf)

Nine (#ulink_754bebfb-4df8-545b-bd64-2cc906eeae57)

Ten (#ulink_2acd90b0-4699-5f9b-bc11-ff3a7318f0bd)

Eleven (#ulink_e2e37625-4493-57fa-8e14-e737fd635c1b)

Twelve (#ulink_9b5c56d6-5b6b-5b3a-afbf-7a8a1d310eb8)

Thirteen (#ulink_49d7a978-025e-5448-b1c8-e511f7bbff8e)

Fourteen (#ulink_05278af9-b4f0-569e-ab4a-d05681590d83)

Fifteen (#ulink_f4682a78-4867-5776-b598-6691d6c9bcaa)

Sixteen (#ulink_c92358e6-40c8-553e-90e0-5f85aca9be96)

Seventeen (#ulink_c9d57bbe-da56-577d-b3b9-de2141c08885)

Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Forty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventy (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventy-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventy-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventy-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventy-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Six Months Later . . . (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Reading group questions (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading... (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

One (#ulink_1fc289c8-a01f-58ff-806c-256b6aa087eb)

London, 2017

I’m that girl you think you know, but you can’t remember where from.

Lying is what I do for a living. It’s what I’m best at: becoming somebody else. The eyes are the only part of me I still recognise in the mirror, staring out beneath the made-up face of a made-up person. Another character, another story, another lie. I look away, ready to leave her behind for the night, stopping briefly to stare at what is written on the dressing-room door:

AIMEE SINCLAIR

My name, not his. I never changed it.

Perhaps because, deep down, I always knew that our marriage would only last until life did us part. I remind myself that my name only defines me if I allow it to. It is merely a collection of letters, arranged in a certain order; little more than a parent’s wish, a label, a lie. Sometimes I long to rearrange those letters into something else. Someone else. A new name for a new me. The me I became when nobody else was looking.

Knowing a person’s name is not the same as knowing a person.

I think we broke us last night.

Sometimes it’s the people who love us the most that hurt us the hardest, because they can.

He hurt me.

We’ve made a bad habit of hurting each other; things have to be broken in order to fix them.

I hurt him back.

I check that I’ve remembered to put my latest book in my bag, the way other people check for a purse or keys. Time is precious, never spare, and I kill mine by reading on set between filming. Ever since I was a child, I have preferred to inhabit the fictional lives of others, hiding in stories that have happier endings than my own; we are what we read. When I’m sure I haven’t forgotten anything, I walk away, back to who and what and where I came from.

Something very bad happened last night.

I’ve tried so hard to pretend that it didn’t, struggled to rearrange the memories, but I can still hear his hate-filled words, still feel his hands around my neck, and still see the expression I’ve never seen his face wear before.

I can still fix this. I can fix us.

The lies we tell ourselves are always the most dangerous.

It was a fight, that’s all. Everybody who has ever loved has also fought.

I walk down the familiar corridors of Pinewood Studios, leaving my dressing room, but not my thoughts or fears too far behind. My steps seem slow and uncertain, as though they are deliberately delaying the act of going home; afraid of what will be waiting there.

I did love him, I still do.

I think it’s important to remember that. We weren’t always the version of us that we became. Life remodels relationships like the sea reshapes the sand; eroding dunes of love, building banks of hate. Last night, I told him it was over. I told him I wanted a divorce and I told him that I meant it this time.

I didn’t. Mean it.

I climb into my Range Rover and drive towards the iconic studio gates, steering towards the inevitable. I fold in on myself a little, hiding the corners of me I’d rather others didn’t see, bending my sharp edges out of view. The man in the booth at the exit waves, his face dressed in kindness. I force my face to smile back, before pulling away.

For me, acting has never been about attracting attention or wanting to be seen. I do what I do because I don’t know how to do anything else, and because it’s the only thing that makes me feel happy. The shy actress is an oxymoron in most people’s dictionaries, but that is who and what I am. Not everybody wants to be somebody. Some people just want to be somebody else. Acting is easy, it’s being me that I find difficult. I throw up before almost every interview and event. I get physically ill and am crippled with nerves when I have to meet people as myself. But when I step out onto a stage, or in front of a camera as somebody different, it feels like I can fly.

Nobody understands who I really am, except him.

My husband fell in love with the version of me I was before. My success is relatively recent, and my dreams coming true signalled the start of his nightmares. He tried to be supportive at first, but I was never something he wanted to share. That said, each time my anxiety tore me apart, he stitched me back together again. Which was kind, if also self-serving. In order to get satisfaction from fixing something, you either have to leave it broken for a while first, or break it again yourself.

I drive slowly along the fast London streets, silently rehearsing for real life, catching unwelcome glimpses of my made-up self in the mirror. The thirty-six-year-old woman I see looks angry about being forced to wear a disguise. I am not beautiful, but I’m told I have an interesting face. My eyes are too big for the rest of my features, as though all the things they have seen made them swell out of proportion. My long dark hair has been straightened by expert fingers, not my own, and I’m thin now, because the part I’m playing requires me to be so, and because I frequently forget to eat. I forget to eat because a journalist once called me ‘plump but pretty.’ I can’t remember what she said about my performance.

It was a review of my first film role last year. A part that changed my life, and my husband’s, for ever. It certainly changed our bank balance, but our love was already overdrawn. He resented my newfound success – it took me away from him – and I think he needed to make me feel small in order to make himself feel big again. I’m not who he married. I’m more than her now, and I think he wanted less. He’s a journalist, successful in his own right, but it’s not the same. He thought he was losing me, so he started to hold on too tight, so tight that it hurt.

I think part of me liked it.

I park on the street and allow my feet to lead me up the garden path. I bought the Notting Hill town house because I thought it might fix us while we continued to remortgage our marriage. But money is a band-aid, not a cure for broken hearts and promises. I’ve never felt so trapped by my own wrong turns. I built my prison in the way that people often do, with solid walls made from bricks of guilt and obligation. Walls that seemed to have no doors, but the way out was always there. I just couldn’t see it.

I let myself in, turning on the lights in each of the cold, dark, vacant rooms.

‘Ben,’ I call, taking off my coat.

Even the sound of my voice calling his name sounds wrong, fake, foreign.

‘I’m home,’ I say to another empty space. It feels like a lie to describe this as my home; it has never felt like one. A bird never chooses its own cage.

When I can’t find my husband downstairs, I head up to our bedroom, every step heavy with dread and doubt. The memories of the night before are a little too loud now that I’m back on the set of our lives. I call his name again, but he still doesn’t reply. When I’ve checked every room, I return to the kitchen, noticing the elaborate bouquet of flowers on the table for the first time. I read the small card attached to them; there’s just one word:

Sorry.

Sorry is easier to say than it is to feel. Even easier to write.

I want to rub out what happened to us and go back to the beginning. I want to forget what he did to me and what he made me do. I want to start again, but time is something we ran out of long before we started running from each other. Perhaps if he’d let me have the children I so badly wanted to love, things might have been different.

I retrace my steps back to the lounge and stare at Ben’s things on the coffee table: his wallet, keys and phone. He never goes anywhere without his phone. I pick it up, carefully, as though it might either explode or disintegrate in my fingers. The screen comes to life and reveals a missed call from a number I don’t recognise. I want to see more, but when I press the button again the phone demands Ben’s passcode. I try and fail to guess several times, until it locks me out completely.

I search the house again, but he isn’t here. He isn’t hiding. This isn’t a game.

Back out in the hall, I notice that the coat he always wears is where he left it, and his shoes are still by the front door. I call his name one last time, so loud that the neighbours on the other side of the wall must hear me, but there’s still no answer. Maybe he just popped out.

Without his wallet, phone, keys, coat or shoes?

Denial is the most destructive form of self-harm.

A series of words whisper themselves repeatedly inside my ears:

Vanished. Fled. Departed. Left. Missing. Disappeared.

Then the carousel of words stops spinning, finally settling on the one that fits best. Short and simple, it slots into place, like a piece of a puzzle I didn’t know I’d have to solve.

My husband is gone.

Two (#ulink_e1455fa8-b37d-5051-a842-225b4cd34fcb)

I wonder where other people go when they turn off the lights at night.

Do they all drift and dream? Or are there some, like me, who wander somewhere dark and cold within themselves, digging around inside the shadows of their blackest thoughts and fears, clawing away at the dirt of memories they wish they could forget? Hoping nobody else can see the place they have sunk down into?

When the race to sleep is beaten by the sound of my alarm, I get up, get washed, get dressed. I do all the things that I would normally do, if this were a normal day. I just can’t seem to do them at a normal speed. Every action, every thought, is painfully slow. As though the night were deliberately holding me back from the day to come.

I called the police before I went to bed.

I wasn’t sure whether it was the right thing to do, but apparently, there is no longer any need to wait twenty-four hours before notifying the police when someone disappears. The word makes it sound like a magic trick, a disappearing act, but I’m the actress, not my husband. The voice of the stranger on the phone was reassuring, even though the words it delivered weren’t. One word in particular, which he repeatedly hissed into my ear: missing.

Missing person. Missing husband. Missing memories.

I can remember the exact expression my husband wore the last time I saw his face, but what happened next is a blur at best. Not because I am forgetful, or a drunk – I am neither of those things – but because of what happened afterwards. I close my eyes, but I can still see him, his features twisted with hate. I blink the image away as though it were a piece of grit, a minor irritant, obstructing the view of us I prefer.

What have we done? What did I do? Why did he make me?

The kind policeman I eventually spoke to, once I’d managed to dial the third and final number, took our details and said that someone would be in touch. Then he told me not to worry.

He may as well have told me not to breathe.

I don’t know what happens next and I don’t like it. I’ve never been a fan of improvisation, I prefer my life to be scripted, planned and neatly plotted. Even now, I keep expecting Ben to walk through the door, deliver one of his funny and charming stories to explain it all away, kiss us better. But he doesn’t do that. He doesn’t do anything. He’s gone.

I wish there were someone else I could call, tell, talk to, but there isn’t.

My husband gradually reorganised my life when we first met, criticising my friends and obliterating my trust in all of them, until we were all we had left. He became my moon, constantly circling, controlling my tides of self-doubt, occasionally blocking out the sun altogether, leaving me somewhere dark, where I was afraid and couldn’t see what was really going on.

Or pretended not to.

The ties of a love like ours twist themselves into a complicated knot, one that is hard to unravel. People would ask why I stayed with him if they knew the truth, and I’d tell them the truth if they did: because I love us more than I hate him, and because he’s the only man I’ve ever pictured myself having a child with. Despite everything he did to hurt me, that was still all I wanted: for us to have a baby and a chance to start again.

A brand-new version of us.

Refusing to let me become a mother was cruel. Thinking I’d just accept his choices as my own was foolish. But I’m good at pretending. I’ve made a living out of it. Papering over the cracks doesn’t mean they’re not there, but life is prettier when you do.

I don’t know what to do now.

I’m trying to carry on like normal, but struggling to remember what that is.

I’ve been running nearly every day for almost ten years, it is something I file away in the slim folder of things I think I am good at, and I enjoy it. I run the same route every single morning, a strict creature of habit. I make myself put on my trainers, shaky fingers struggling to remember how to tie laces they’ve tied a thousand times before. Then I tell myself that staring at the bare walls isn’t going to help anyone or bring him back.

My feet find their familiar rhythm: fast but steady, and I listen to music to disguise the soundtrack of the city. The adrenaline rush kicks in to dismantle the pain, and I push myself a little harder. I run past the pub on the corner where Ben and I used to go drinking on Friday nights, before we forgot who and how to be with each other. Then I run past the council tower blocks and the millionaires’ playground of terraced luxury on the neighbouring street; the haves and have-nots side by side, at least in proximity.

Moving to an expensive corner of West London was Ben’s idea. I was away in LA when we bought the place; fear persuaded me it was the right thing to do. I didn’t even step inside before we owned it. When I finally did, the whole house was quite transformed from the photos I had seen online. Ben renovated our new home all by himself: new fixtures and fittings for the brand-new us we thought we could and should be.

As I run around the corner of the street, my eyes find the bookshop. I try not to look, but it’s like the scene of an accident and I can’t help it. It’s where we arranged to meet for our first date. He knew about my love of books, which is why he chose this place. I arrived a little early that night, filled with anticipation and nerves, and browsed the shelves while I waited. Fifteen minutes later, when my date still hadn’t turned up, my anxiety levels were peaking.

‘Excuse me, are you Aimee?’ asked an elderly gentleman with a kind smile.

I felt confused, a little sick; he was nothing like the handsome young man in the profile picture I had seen. I considered fleeing from the shop.

‘Another customer came in earlier; he bought this and asked me to give it to you. He said it was a clue.’ The man beamed as though this were the most fun he’d had in years. Then he held out a neatly wrapped brown-paper parcel. With the tension removed from the situation, things seemed to fall into place and I realised this was the owner of the shop, not my date. I thanked him and took what I guessed was a book, grateful when he left me alone to unwrap it. Inside, I found one of my childhood favourites: The Secret Garden. It took a while for the penny to drop, but then I remembered that the florist on the corner shared the same name as the book.

The woman in the flower shop grinned as soon as I walked in, my entrance accompanied by the tinkle of a bell on her door.

‘Aimee?’

When I nodded, she presented me with a bouquet of white roses. There was a note:

Roses are white.

So sorry I’m late.

Can’t wait for tonight.

You’re my perfect date.

I read it three times, as though trying to translate the words, then noticed the florist still smiling in my direction. People staring at me has always made me feel uncomfortable.

‘He said he’d meet you at your favourite restaurant.’

I thanked her and left. We didn’t have a favourite restaurant, having never eaten out together, so I walked along the high street carrying my book and flowers, enjoying the game. I replayed our email conversations in my mind and remembered one about food. His preferences had all been so fancy, mine . . . less so. I had regretted telling him my favourite meal and blamed my upbringing.

The man behind the counter at the fish-and-chips shop smiled. I was a regular back then.

‘Salt and vinegar?’

‘Yes please.’

He shovelled some chips into a paper cone, then gave them to me, along with a ticket for a film screening later that night. The chips were too hot, and I was too anxious to eat them as I hurried along the road. But as soon as I saw Ben standing outside the cinema, all my fear seemed to disappear.

I remember our first kiss.

It felt so right. We had a connection I could neither fathom or explain, and we slotted together as though we were meant to be that way. I smile at the memory of who we were then. That version of us was good. Then I stumble on the uneven pavement outside the cinema, and it brings me back to the present. Its doors are closed. The lights are off. And Ben is gone.

I run a little faster.

I pass the charity shops, wondering if the clothes in the windows were donated in generosity or sorrow. I run past the man pushing a broom along the pavement, sweeping away the litter of other people’s lives. Then I run past the Italian restaurant where the waitress recognised me the last time we ate there. I haven’t been back since; it feels as if I can’t.

I am paralysed with a unique form of fear when strangers recognise me. I just smile, try to say something friendly, then retreat as fast as I can. Thankfully it doesn’t happen too often. I’m not A-list. Not yet. Somewhere between a B and C I suppose, a bit like my bra size. The version of myself I wear in public is far more attractive than the real me. It’s been carefully tailored, a cut above my standard self; she’s someone nobody should see.

I wonder when his love for me ran out?

I take a shortcut through the cemetery and the sight of a child’s grave fills me with grief, redirecting my mind from thoughts of who we were, to who we might have been, had life unfolded differently. I try to hold on to the happy memories, pretend that there were more than there were. We are all programmed to rewrite our past to protect ourselves in the present.

What am I doing?

My husband is missing. I should be at home, crying, calling hospitals, doing something. The memory interrupts my thoughts but not my footsteps, and I carry on. I only stop when I reach the coffee shop, exhausted by my own bad habits: insomnia and running away from my problems.

It’s already busy, filled with overworked and underpaid Londoners needing their morning fix, sleep and discontentment still in their eyes. When I reach the front of the queue, I ask for my normal latte and make my way to the till. I use contactless to pay, and disappear inside myself again until the unsmiling cashier speaks in my direction. Her blonde hair hangs in uneven plaits on either side of her long face, and she wears a frown like a tattoo.

‘Your card has been declined.’

I don’t respond.

She looks at me as though I might be dangerously stupid. ‘Do you have another card?’ Her words are deliberately slow and delivered with increased volume, as though the situation has already exhausted her of all patience and kindness. I feel other sets of eyes in the shop joining hers, all converging on me.

‘It’s two pounds forty. It must be your machine, please try it again.’ I’m appalled by the pathetic sound impersonating my voice coming from my mouth.

She sighs, as though she is doing me an enormous favour, and making a huge personal sacrifice, before stabbing the till with her nail-bitten finger.

I hold out my bank card, fully aware that my hand is trembling and that everyone can see.

She tuts, shakes her head. ‘Card declined. Have you got any other way of paying, or not?’

Not.

I take a step back from my untouched coffee, then turn and walk out of the shop without another word, feeling their eyes follow me, their judgment not far behind.

Ignorance isn’t bliss, it’s fear postponed to a later date.

I stop outside the bank and allow the cash machine to swallow my card, before entering my pin and requesting a small amount of money. I read the unfamiliar and unexpected words on the screen twice:

SORRY

INSUFFICIENT FUNDS AVAILABLE

The machine spits my card back out in electronic disgust.

Sometimes we pretend not to understand things that we do.

I do what I do best instead: I run. All the way back to the house that was never a home.

As soon as I’m inside, I pull out my phone and dial the number on the back of my bank card, as though this conversation could only be had behind closed doors. Fear, not fatigue, withholds my breath, so that it escapes my mouth in a series of spontaneous bursts, disfiguring my voice. Getting through the security questions is painful, but eventually the woman in a distant call centre asks the question I’ve been waiting to hear.

‘Good morning, Mrs Sinclair. You have now cleared security. How can I help you?’

Finally.

I listen while a stranger calmly tells me that my bank account was emptied, then closed yesterday. Over ten thousand pounds had been sitting in it – the account I reluctantly agreed to make in joint names, when Ben accused me of not trusting him. Turns out I might have been right not to. Luckily, I’ve squirrelled most of my earnings away in accounts he can’t access.

I stare down at Ben’s belongings still sitting on the coffee table, then cradle my phone between my ear and shoulder to free up my hands. It feels a little intrusive to go through his wallet – I’m not that kind of wife – but I pick it up anyway. I peer inside, as though the missing ten thousand pounds might be hidden between the leather folds. It isn’t. All I find is a crumpled-looking fiver, a couple of credit cards I didn’t know he had, and two neatly folded receipts. The first is from the restaurant we ate at the last time I saw him, the second is from the petrol station. Nothing unusual about that. I walk to the window and peel back the edge of the curtain, just enough to see Ben’s car parked in its usual spot. I let the curtain fall, and put the wallet back on the table, exactly how I found it. A marriage starved of affection leaves an emaciated love behind; one that is frail, easy to bend and break. But if he was going to leave me and steal my money, then why didn’t he take his things with him too? Everything he owns is still here.

It doesn’t make any sense.

‘Mrs Sinclair, is there anything else I can help you with today?’ The voice on the phone interrupts my confused thoughts.

‘No. Actually, yes. I just wondered if you could tell me what time my husband closed our joint account?’

‘The final withdrawal was made in branch at seventeen twenty-three.’ I try to remember yesterday – it seems so long ago. I’m fairly sure I was home from filming by five at the latest, so I would have been here when he did it. ‘That’s strange . . . ’ she says.

‘What is?’

She hesitates before answering.

‘Your husband didn’t withdraw the money or close the account.’

She has my full attention now.

‘Then who did?’

There is another long pause.

‘Well, according to our records, Mrs Sinclair, it was you.’

Three (#ulink_16562561-f76d-5693-8907-7e7181a897c6)

‘Mrs Sinclair?’ The bank’s call centre sounds very far away now, even farther than before, and I can’t answer. I’ve come undone. Time seems like something I can no longer tell, and it feels as if I’m tumbling down a hill too fast with nothing to break my fall.

I think I’d remember if I went to the bank and closed our account.

I hang up as soon as I hear the knock at the door and run to answer it, practically tripping over my feet. I’m certain that Ben and a logical explanation will be waiting behind it.

I’m wrong.

A middle-aged man and a young girl wearing cheap suits are standing on my doorstep. He looks like a guy with friends in low places, and she looks like lamb dressed as mutton.

‘Mrs Sinclair?’ she says, coating my name in her Scottish accent.

‘Yes?’ I wonder if they might be selling something door-to-door, like double glazing or God or, even worse, whether they might be journalists.

‘I’m Detective Inspector Alex Croft and this is Detective Sergeant Wakely. You called about your husband,’ she says.

Detective? She looks like she should still be in school.

‘Yes, I did, please come in,’ I reply, already forgetting their names and ranks. It’s very loud inside my head right now, and my mind is unable to process the additional information.

‘Thank you. Is there somewhere we could all sit down?’ she asks, and I lead them into the lounge.

Her petite body is folded into a nondescript black trouser suit, with a white shirt tucked underneath. The ensemble is not unlike a school uniform. Her face is plain but pretty, and without a smudge of make-up. Her shoulder-length mousy hair is so straight it looks as though she might have ironed it at the same time as her shirt. Everything about her is neat and uncommonly tidy. I think she must be new at this; perhaps he is training her. I wasn’t expecting detectives to appear on my doorstep: a uniformed officer perhaps, but not this. I wonder why I’m receiving special treatment and shrink away from the potential answers lining up inside my head.

‘So, your husband is missing,’ she prompts as I sit down opposite them both.

‘Yes.’

She stares, as though waiting for me to say more. I look at him, then back at her, but he doesn’t seem to be much of a talker, and her expression remains unchanged.

‘Sorry, I’m not really sure how this works.’ I already feel flustered.

‘How about you start by telling us when you last saw your husband?’

‘Well . . . ’ I pause to think for a moment.

I remember the screaming argument, his hands around my throat. I remember what he said and what he did. I see them share a look and some unspoken opinions, then remember I need to answer the question.

‘Sorry. I’ve not slept. I saw him the night before last. And there’s something else I should tell you . . . ’

She leans forward in her chair.

‘Someone has emptied our joint account.’

‘Your husband?’ she asks.

‘No, someone . . . else.’

She frowns, overworked folds appearing on her previously smooth forehead. ‘Was it a lot of money?’

‘About ten thousand pounds.’

She raises a neatly plucked eyebrow. ‘I’d say that was a lot.’

‘I also think you should know that I had a stalker a couple of years ago. It’s why we moved to this house. You’ll have a record of it; we reported it to the police at the time.’

‘Seems unlikely that this and that are related, but we’ll certainly look into it.’ It seems odd to me that she is being so dismissive of something that might be important. She leans back in her chair again, frown still firmly in place, fast becoming a permanent feature. ‘When you called last night, you told the officer you spoke to that all your husband’s personal belongings are still here, is that right? His phone, keys and wallet, even his shoes?’ I nod. ‘Mind if we take a look around?’

‘Of course, whatever you need.’

I follow them through the house, not sure whether I’m supposed to or not. They don’t talk, at least not with words, but I pick up on the silent dialogue they exchange between glances, as they search every room. Each one is filled with memories of Ben, some of which I would rather forget.

When I try to pinpoint the exact moment we started to unfold, I realise it was long before I got my first film role and went to LA. I’d been away filming in Liverpool for a few days, a small part in a BBC drama, nothing special. I was so tired when I got back, but Ben insisted on going out for dinner, pulled his warning face when I said I’d rather not. I dropped my earring getting ready, and the back of it disappeared beneath our bed. That tiny sliver of silver was the butterfly effect that changed the course of our marriage. I never found it. I found something else instead: a red lipstick that did not belong to me and the knowledge that my husband didn’t either. I suppose I wasn’t completely surprised; Ben is a good-looking man, and I’ve seen how other women look at him.

I never mentioned what I found that day. I didn’t say a word. I didn’t dare.

The female detective spends a long time looking around our bedroom, and I feel as though my privacy is being unpicked as well as invaded. I was taught as a child not to trust the police and I still don’t.

‘So, remind me again of the exact time you last saw your husband,’ she says.

When he lost his temper and turned into someone I no longer recognised.

‘We were having a meal at the Indian restaurant on the high street. I left a bit earlier than him . . . I wasn’t feeling well.’

‘You didn’t see him when he got home?’

Yes.

‘No, I had an early start the next day. I’d gone to bed by the time he got back.’ I know she knows I’m lying. I’m not even sure why I am, a mixture of shame and regret perhaps, but lies don’t come with gift receipts; you can’t take them back.

‘You don’t share a bedroom?’ she asks.

I’m not sure how or why this is relevant. ‘Not always; we both have quite hectic work schedules – he’s a journalist and I’m—’

‘But you did hear him come home that night.’

Heard him. Smelt him. Felt him.

‘Yes.’

She notices something behind the door, and takes a pair of blue latex gloves from her pocket. ‘And this is the bedroom you sleep in?’

‘It’s where we both sleep most of the time, just not that night.’

‘Do you ever sleep in the spare room, Wakely?’ she asks her silent companion.

‘Used to, if we’d had a fight, when we still had enough time and energy to argue. But none of our bedrooms are spare any more, they’re all full of hormonal teenagers.’

It speaks.

‘Any reason why you have a bolt on the inside of your bedroom door, Mrs Sinclair?’ she asks.

At first, I don’t know what to say.

‘I told you, I had a stalker. It made me take home security pretty seriously.’

‘Any reason why the bolt is busted?’ She swings the door back to reveal the broken metal shape and splintered wood on the frame.

Yes.

I feel my cheeks turn red. ‘It got jammed a little while ago, my husband had to force it open.’ She looks back at the door and nods slowly, as though it is an effort.

‘Got an attic?’

‘Yes.’

‘Basement?’

‘No. Do you want to see the attic?’

‘Not this time.’

This time? How many times are there going to be?

I follow them back downstairs and the tour of the house concludes in the kitchen.

‘Nice flowers.’ She looks at the expensive bouquet on the table and reads the card. ‘What was he sorry for?’

‘I’m not sure, I never got to ask him.’

If she thinks something, her face doesn’t show it. ‘Great garden.’ She stares out through the glass folding doors. The looked-after lawn is still wearing its stripes from the last time Ben mowed it, and the hardwood decking practically sparkles in the early-morning sun.

‘Thank you.’

‘It’s a nice place, like a show home or something you’d see in a magazine. What’s the word I’m looking for . . . ? Minimalist. That’s it. No family photos, books, clutter . . . ’

‘We haven’t unpacked everything yet.’

‘Just moved in?’

‘About a year ago.’ They both look up then. ‘I’m away a lot for work. I’m an actress.’

‘Oh, don’t worry, Mrs Sinclair. I know who you are. I saw you in that TV show last year, the one where you played a police officer. I . . . enjoyed it.’

Her lopsided smile fades, making me think that she didn’t. I stare back, feeling even more uncomfortable than before, and completely clueless about how to reply.

‘Do you have a recent photograph of your husband that we can take with us?’ she asks.

‘Yes, of course.’ I walk through to the mantelpiece in the lounge, but there is nothing there. I look around the room at the bare walls, and sparse shelves, and realise that there is not a single photo of him, or me, or us. There used to be a framed picture of our wedding day in here, I don’t know where it has gone. Our big day was rather small; just the two of us. It led to even smaller days, until we struggled to find each other in them. ‘I might have something on my phone. Could I email it to you or do you need a hard copy?’

‘Email is fine.’ That unnatural smile spreads across her face again, like a rash.

I pick up my mobile and start to scroll through the photos. There are plenty of the cast and crew working on the film, lots of Jack – my co-star – a few of me, but none of Ben. I notice my hands are trembling, and when I look up, I see that she has noticed too.

‘Does your husband have a passport?’

Of course he has a passport. Everyone has a passport.

I hurry to the sideboard where we keep them, but it isn’t there. Neither is mine. I start to pull things out of the drawer, but she interrupts my search.

‘Don’t worry, I doubt your husband has left the country. Based on what we know so far, I don’t expect he is too far away.’

‘What makes you say that?’

She doesn’t respond.

‘DI Croft has solved every case she’s been assigned since joining the force,’ says the male detective, like a proud father. ‘You’re in safe hands.’

I don’t feel safe, I feel scared.

‘Mind if we take these?’ She slips Ben’s phone and wallet inside a clear plastic bag without waiting for an answer. ‘Don’t worry about the photo for now, we can collect it next time.’ She removes her blue plastic gloves and heads out into the hall.

‘Next time?’

She ignores me again and they let themselves out. ‘We’ll be in touch,’ he says, before walking away.

I sink down onto the floor once I’ve closed the door behind them. I felt is if they were silently accusing me of something the whole time they were here, but I don’t know what. Do they think I murdered my husband and buried him beneath the floorboards? I have an urge to open the door, call them back and defend myself, tell them that I haven’t killed anyone.

But I don’t do that.

Because it isn’t true.

I have.

Four (#ulink_10957104-7d02-56cf-9687-6c7c9fdd7403)

Galway, 1987

I was lost before I was even born.

My mummy died that day and he never forgave me.

It was my fault – I was late and then I turned the wrong way. I’m still not very good at looking where I am going.

When I was stuck inside her belly, not wanting to come out for some reason that I do not remember, the doctor told my daddy he’d have to choose between us, said he couldn’t save us both. Daddy chose her, but he didn’t get what he wanted. He got me instead, and that made him sad and angry for a very long time.

My brother told me the story of what happened. Over and over.

He’s much older than me, so he knows things that I don’t.

He says I killed her.

I’ve tried awful hard not to kill things since then. I step over ants, pretend not to see spiders, and when my brother takes me fishing, I empty the net back into the sea. He says our daddy was a kind man before I broke his heart.

I hear them, down in the shed together.

I know I’m not allowed, but I want to know what they are doing.

They do lots of things without me. Sometimes I watch.

I stand on the old tree stump we use for chopping wood, and peek through the tiny hole in the shed wall. My right eye finds the chicken first, the white one we call Diana. There is a princess with that name in England – we named the chicken after her. Daddy’s giant fist is wrapped around its throat, and its feet are tied together with a piece of black string. He turns the bird upside down and it hangs still, except for its little black eyes. They seem to look in my direction, and I think that chicken knows I’m watching something I shouldn’t.

My brother is holding an axe.

He’s crying.

I’ve never seen him cry before. I’ve heard him through my bedroom wall, when Daddy uses his belt, but this is the first time I’ve seen his tears. His fifteen-year-old face is red and blotchy and his hands are shaking.

The first swing of the axe doesn’t do it.

The chicken flaps its wings, thrashing like a banshee, blood spurting from its neck. Daddy clouts my brother around the head, makes him swing the axe again. The noise of the chicken screaming and my big brother crying start to sound the same in my ears. He swings and misses, Daddy hits him again, so hard he falls down on his knees, the chicken’s blood spraying all over their dirty white shirts. My brother swings a third time and the bird’s head falls to the floor, its wings still flapping. Red feathers that used to be white.

When Daddy has gone, I creep into the shed and sit down next to my brother. He’s still crying and I don’t know what to say, so I slip my hand into his. I look at the shape our fingers make when joined together, like pieces of a puzzle that shouldn’t fit, but do – my hands are small and pink and soft, his hands are big and rough and dirty.

‘What do you want?’ He snatches his hand away and uses it to wipe his face, leaving a streak of blood on his cheek.

I only want to be with him, but he is waiting for an answer, so I make one up. I already know it is the wrong one.

‘I thought you could walk me to town, so I could show you the red shoes I wanted for my birthday again.’ I’ll be six next week. Daddy said I could have a present this year, if I was good. I haven’t been bad, and I think that’s the same thing.

My brother laughs – not his real laugh, the unkind one. ‘Don’t you get it? We can’t afford red shoes, we can barely afford to eat!’ He grabs me by the shoulders, shakes me a little, the way that Daddy shakes him when Daddy is cross. ‘People like us don’t get to wear red bloody shoes, people like us are born in the dirt and die in the dirt. Now fuck off and leave me alone!’

I don’t know what to do. I feel strange and my mouth forgets how to make words.

My brother has never spoken to me like this before. I can feel the tears trying to leak out of my eyes, but I won’t let them. I try to put my hand in his again. I just want him to hold it. He shoves me, so hard that I fall backwards and hit my head on the chopping block, chicken blood and guts sticking to my long black curly hair.

‘I said, fuck off, or I’ll chop your bloody head off too,’ he says, waving the axe.

I run and I run and I run.

Five (#ulink_54b017c5-2977-5e4f-96d3-a65efb298589)

London, 2017

I run from the car park to the main building at Pinewood. I’m never late for anything, but the unscheduled police visit this morning has thrown me off balance in more ways than one.

My husband has disappeared and so has ten thousand pounds of my money.

I can’t solve the puzzle, because no matter how I slot the pieces together, there are still too many missing to complete the picture. I remind myself that I have to keep it together for just a little while longer. The film is almost finished, just three more scenes to shoot. I bury my personal problems somewhere out of reach as I hurry along corridors towards my dressing room. As I turn the final corner, still distracted, I walk straight into Jack, my co-star.

‘Where have you been? Everyone is looking for you,’ he says.

I glance down at his hand gripping the sleeve of my jacket and he removes it. His dark eyes see straight through me and I wish they didn’t, it makes it almost impossible to lie to him, and I can’t always speak the truth; my inability to trust people won’t allow it. Sometimes, when you spend this long working with someone, when you get this close, it’s hard to hide the real you from them completely.

Jack Anderson is consciously handsome. His face has earned him a small fortune and more justifiably than his intermittent acting skills. His uniform of chinos and slim-fitted shirts are cut to flatter and hint at the muscular shape of him underneath. He wears his smile like a prize and his stubble like a mask. He’s a bit older than me, but the grey flecks in his brown hair only seem to make him more attractive.

I am aware that we have a connection. And I am aware that he is aware of that, too.

‘Sorry,’ I say.

‘Tell it to the crew, not me. Just because you’re beautiful, doesn’t mean the world will wait for you to catch up with it.’

‘Don’t say that.’ I look over my shoulder.

‘What, beautiful? Why? It’s true, you’re the only one who can’t see it, which just makes you even more enchanting.’ He takes a step closer. Too close. I take a tiny step back.

‘Ben didn’t come home last night,’ I whisper.

‘So?’

I frown and his features readjust themselves, to reflect the caution and concern most people would display in these circumstances. He lowers his voice. ‘Does he know about us?’

I stare at his face, so serious all of a sudden. Then the creases fold and fan around the corners of his mischievous eyes, and he laughs at me. ‘There’s a journalist waiting in your dressing room, too, by the way.’

‘What?’ He may as well have said assassin.

‘Apparently your agent arranged the interview, and they only want to speak to you, not me. Not that I’m jealous . . . ’

‘I don’t know anything about—’

‘Yeah, yeah. Don’t worry, my bruised ego will regenerate itself, always does. She’s been in there for twenty minutes. I don’t want her writing something shit about the film because you can’t set an alarm, so you might want to be a little more tout suite about it.’ He often adds a random French word to his sentences, I’ve never understood why. He isn’t French.

Jack walks off down the corridor without another word, in either language, and I question what it is about him that I find so attractive. Sometimes I wonder if I only ever want things I think I can’t have.

I don’t know anything about any interview, and I would never have agreed to do one today if I had. I hate interviews. I hate journalists; they’re all the same – trying to uncover secrets that aren’t theirs to share. Including my husband. Ben works behind the scenes as a news producer at TBN. I know he spent time in warzones before we met; his name was mentioned in online articles by some of the correspondents he worked with. I’ve no idea what he is working on now, he never seems to want to talk about it.

I found him romantic and charming at first. His Irish accent reminded me of my childhood, and bred a familiarity I wanted to climb inside and hide in. Whenever I think it might be the end, I remember the beginning. We married too fast and loved too slowly, but we were happy for a while, and I thought we wanted the same thing. Sometimes I wonder whether the horrors of the world he saw because of his job changed him; Ben is nothing like the other journalists I meet for work.

I know a lot of the showbiz and entertainment reporters now; the same familiar faces turn up at junkets, premieres and parties. I wonder if it might be one of the ones I like, someone who has been kind about my work before, someone I’ve met. That might be okay. If it’s someone I haven’t met before, my hands will shake, I’ll start to sweat, my knees will wobble and then, when my unknown adversary picks up on my absolute terror, I’ll lose the ability to form coherent sentences. If my agent had any understanding of what these situations do to me, he wouldn’t keep landing me in them. It’s like a parent dropping a child who is scared of water into the deep end, presuming that the child will swim, not sink. One of these days I know I’m going to drown.

I text my agent, it’s unlike Tony to set something up and not tell me. Other actresses might throw their toys out of their prams when things don’t go according to plan – I’ve seen them do it – but I’m not like that, and hope I won’t ever be; I know how lucky I am. At least a thousand other people wish they could walk in my shoes, and they are more deserving than I am to wear them. I’m still fairly new to this level of this game, and I’ve got too much to lose. I can’t go back to the start, not now. I worked too hard and it took so long to get here.

I check my phone. There’s no response from Tony, but I can’t keep the journalist waiting any longer. I paint on the smile I have perfected for others, before opening the door with my name on, and finding someone else sitting in my chair, as though she belongs there.

She doesn’t.

‘I’m so sorry to have kept you waiting, great to see you,’ I lie, holding out my hand, trying to keep it steady.

Jennifer Jones smiles up at me as though we are old friends. We are not. She’s a journalist I despise, who has been horribly unkind about me in the past, for reasons I’ll never understand. She’s the bitch who called me ‘plump but pretty’ when my first film came out last year. I call her Beak Face in return, but only in the privacy of my own thoughts. Everything about her is too small, especially her mind. She leaps up from the chair, flutters around me like a sparrow on speed, then grips my fingers in her tiny, cold, claw-like hand, giving my own an over-enthusiastic shake. Last time we met, I’m not convinced she had seen one frame of the film I was there to talk about. She’s one of those journalists who thinks that because she interviews celebrities, she is one too. She isn’t.

Beak Face is middle-aged and dresses like her daughter would, had she been willing to pause her career long enough to have one. Her neat brown hair is cut into a style that was almost fashionable a decade ago, her cheeks are too pink and her teeth are unnaturally white. She’s a person whose story has already been written, and she’ll never change her own ending, no matter how hard she tries. From what I’ve read about her online, she wanted to be an actress herself when she was younger. Perhaps that’s why she hates me so much. I watch her tiny mouth twitch and spit as she squawks fake praise in my direction, my mind already racing ahead, trying to anticipate the verbal grenades she plans to throw at me.

‘My agent didn’t mention anything about an interview . . . ’

‘Oh, right. Well, if you’d rather not? It’s just for the TBN website, no cameras, just little old me. So you don’t need to worry about your hair or how you look at the moment . . . ’

Bitch.

She winks and her face looks as if it has suffered a temporary stroke.

‘I can come back another time if . . . ’

I force another smile in reply and sit down opposite her, my hands knotted together in my lap to stop them from shaking. My agent wouldn’t have agreed to this unless he thought it was a good idea. ‘Fire away,’ I say. Feeling like I really am about to get shot.

She takes an old-fashioned notebook from what looks like a school satchel she probably stole from a child on the street. I’m surprised, most journalists I meet nowadays record their interviews on their phones. I guess her methods, like her hair, are stuck in the past.

‘Your acting career started when you got a scholarship to RADA when you were eighteen, is that correct?’

No, I started acting long before that, when I was much, much younger.

‘Yes, that’s right.’ I remind myself to smile. Sometimes I forget.

‘Your parents must have been very proud.’

I don’t answer personal questions about my family, so I just nod.

‘Did you always want to act?’

This one is easy, I get asked this all the time and the answer always seems to go down well. ‘I think so, but I was extremely shy when I was a child . . . ’

I still am.

‘There were auditions for my school’s production of The Wizard of Oz when I was fifteen, but I was too scared to go along. The drama teacher put a list of who got what part on a notice board afterwards; I didn’t even read it. Someone else told me that I got the part of Dorothy and I thought they were joking, but when I checked, my name really was there, right at the top of the list – Dorothy: Aimee Sinclair. I thought it was a mistake, but the drama teacher said it wasn’t. He said he believed in me because he knew I couldn’t. Nobody had ever believed in me before. I learned my lines and I practised the songs and I did my very best for him, not for me, because I didn’t want to let him down. I was surprised when people thought I was good, and I loved being on that stage. From that moment on, acting was all I ever wanted to do.’

She smiles and stops scribbling. ‘You’ve played a lot of different roles in the last couple of years.’

I’m waiting for the question, but realise there isn’t one. ‘Yes. I have.’

‘What’s that been like?’

‘Well, as an actor, I really enjoy the challenge of becoming different people and portraying different characters. It’s a lot of fun and I relish the variety.’

Why did I use the word relish? We’re not talking about condiments.

‘So, you like pretending to be someone you’re not?’

I hesitate without meaning to, still recoiling from my previous answer. ‘I guess you could put it that way, yes. But then I think we’re all guilty of that from time to time, aren’t we?’

‘I imagine it must be hard sometimes, to remember who you really are when the cameras aren’t on you.’

I sit on my hands to stop myself from fidgeting. ‘Not really, no, it’s just a job. A job that I love and that I’m very grateful for.’

‘I’m sure you are. With this latest movie your star really is rising. How did you feel when you got the part in Sometimes I Kill?’

‘I was thrilled.’ I realise I don’t sound it.

‘This role has you playing a married woman who pretends to be nice, but in reality has done some pretty horrific things. Was it a challenge to take on the part of someone so . . . damaged? Were you worried that the audience wouldn’t like her once they knew what she’d done?’

‘I’m not sure we want to give away the twist in any preview pieces.’

‘Of course, my apologies. You mentioned your husband earlier . . . ’

I’m pretty sure I didn’t.

‘How does he feel about this role? Has he started sleeping in the spare room in case you come home still in character?’

I laugh, hoping it sounds genuine. I start to wonder if Ben and Jennifer Jones might know each other. They both work for TBN, but in very different departments. It’s one of the world’s biggest media companies, so it has never occurred to me that their paths might have crossed. Besides, Ben knows how much I hate this woman; he would have mentioned if he knew her.

‘I don’t tend to answer personal questions, but I don’t think my husband would mind me saying he’s really looking forward to this film.’

‘He sounds like the perfect partner.’

I worry about what my face might be doing now, and focus all of my attention on reminding it to smile. What if she does know him? What if he told her that I’d asked for a divorce? What if that’s why she’s really here? What if they are working together to hurt me? I’m being paranoid. It will be over soon. Just smile and nod. Smile and nod.

‘You’re not like her then, the main character in Sometimes I Kill?’ she asks, raising an overplucked eyebrow in my direction, and peering at me over her notepad.

‘Me? Oh, no. I don’t even kill spiders.’

Her smile looks as if it might break her face. ‘The character you’re playing tends to run away from reality. Was that something you found easy to relate to?’

Yes. I’ve spent a lifetime running away.

A knock at the door saves me. I’m needed on set.

‘I’m so sorry, I think that might be all we have time for, but it’s been lovely to see you,’ I lie. My phone vibrates with a text as she packs up her things and leaves my dressing room. I take it out as soon as I’m alone again and read the message. It’s from Tony.

We need to talk, call me when you can. And no, I didn’t arrange or agree to any interviews, so tell them to bugger off. Don’t speak to any journalists before speaking to me for the time being, no matter what they say.

I feel like I might cry.

Six (#ulink_41573036-8fdd-5bb0-8511-61e32f0f2563)

Galway, 1987

‘There now, why are you spoiling that pretty face with all those ugly tears?’

I look up to see a woman smiling down at me outside the closed shop. I ran all the way here after my brother shouted at me. All I wanted was to look at the red shoes I thought someone might buy me for my birthday this year, but they’re gone from the window. Some other little girl is wearing them, a little girl with a proper family and pretty shoes.

‘Have you lost your mummy?’ the woman asks.

I start to cry all over again. She takes a crumpled tissue from the sleeve of her white knitted cardigan, and I wipe my eyes. She’s very pretty. She has long dark curly hair, a bit like mine, and big green eyes that forget to blink. She’s a bit older than my brother, but much younger than my daddy. Her dress is covered in pink and white flowers, as if she were wearing a meadow, and she is the spit of how I imagine my mummy would have looked. If I hadn’t killed her with a wrong turn. I blow my nose and hand back the snotty rag.

‘Well now, don’t you be worrying yourself – worrying never solved anything. I’m sure we can find your mummy.’ I don’t know how to tell her that we can’t. She holds out her hand, and I see that her nails are the same colour red as the shoes I wish were mine. She waits for me to hold it, and when I don’t she bends down, until her face is level with my own.

‘Now, I know you’ve probably been told not to talk to strangers, and that there are some bad people in the world, and that’s good if you have, because it’s true. But that’s also why I can’t leave you here on your own. It’s getting late, the shops are closed, the streets are empty and if something were to happen to you, well, I’d never forgive myself. My name is Maggie, what’s yours?’

‘Ciara.’

‘Hello, Ciara. It’s nice to meet you.’ She shakes my hand. ‘There, now we’re not strangers any more.’ I smile, she’s funny and I like her. ‘So, why don’t you come with me and if we can’t find your mummy, we can call the police and they can take you home. Does that sound all right with you?’ I think about it. It’s an awful long walk back home, and it is getting dark already. I take the nice lady’s hand and walk beside her, even though I know home is back the other way.

Seven (#ulink_1aaa9b66-58ac-5c38-bee5-acff7c885f40)

London, 2017

Jack takes my hand in his. He stares at me across the hotel restaurant table, and it feels as though everyone in the room is watching us. It’s impossible not to form a relationship off-screen when you spend this many months filming together. I know he’s enjoying this moment and his touch feels more intimate than it should. I’m scared of what is about to happen, but it’s far too late for that now, too late to pretend we both don’t know what happens next. I can see people staring in our direction, people who know who we are, and I think he senses my apprehension, gently squeezing my fingers in silent reassurance. There’s really no need. When I make my mind up about something it’s almost impossible for anyone to change it, including me.

He pays the bill with cash and stands, leaving the table without another word. I wipe my mouth with the napkin from my lap, even though I’ve hardly eaten a thing. I think about Ben for the briefest of moments, instantly wishing that I hadn’t, because the thought of him is hard to extinguish once inside my head. I can’t remember the last time Ben took me for a romantic meal or made me feel attractive. But then, the present is always a superior time; looking down its nose at the past, turning away from the temptations of the future. I ignore the fear trying to hold me back and follow Jack. Despite my hesitation, I always knew that I would when the time came.

He gets into the hotel lift up ahead of me. The doors start to close but I don’t run to catch up, I don’t need to. The metal jaws slide open again, right on time, to swallow me whole as I step inside. We don’t speak in the lift, just stand side by side. We’ve evolved as a species to hide our lust, like a dirty secret, even though finding other people attractive is exactly what we were designed to do. Still, I’ve never done anything like this before.

I’m aware of other people in the lift around us, aware of being watched. With each floor we pass I feel more anxious about our final destination. I always knew this was going to happen, even the first time we met. My heart changes speed inside my ears, I’m breathing too fast and I worry that he can tell how scared I am of what we’re about to do. His hand brushes mine as we step out on to the seventh floor, by accident I think. I wonder if he might hold it, but he doesn’t. He is not here to offer romance. That isn’t what this is and we both know that.

He slots the key card into the door, and for a moment I think it won’t work. Then I hope it won’t, something to buy me just a little bit more time. I don’t want to do this, which makes me wonder why I am. I seem to have spent my life doing things I don’t want to.

Inside the room, he takes off his jacket, flinging it onto the bed, as though he is angry with me, as though I have done something wrong. His handsome face turns to look in my direction, his features twisted into something resembling hate and disgust, as though he is mirroring my own thoughts about myself in this moment, in this room.

‘I think we need to have a talk, don’t you? I’m married.’ His final two words are like an accusation.

‘I know,’ I whisper.

He takes a step closer. ‘And I love my wife.’

‘I know.’ I’m not here for his love, she can keep that. I look away, but he takes my face in his hands and kisses me. I stand perfectly still, as though I don’t know what to do, and for a moment I worry that I can’t remember how. He is so gentle at first, careful, as though worried he might break me. I close my eyes – it’s easier to do this with them closed – and I kiss him back. He changes gear faster than I was anticipating, his hands sliding down from my cheeks, to my neck, to the dress covering my breasts, his fingertips tracing the outline of my bra beneath the thin cotton. He stops and pulls away.

‘Fuck. What the fuck am I doing?’

I try to remember how to breathe.

‘I know, I’m sorry,’ I reply, as though this were all my fault.

‘It’s like you’re inside my head.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I say again. ‘I think about you all the time. I know I shouldn’t, and I promise I’ve tried so hard not to, but I can’t help it—’ My eyes fill with tears. He’s at least ten years older than me, and I feel like an inexperienced child.

‘It’s okay. This, whatever this is, is not your fault. I think about you too.’

I stop crying when he says that, as though the latest sentence to have spilled from his mouth changes everything. He lifts my chin, turning my face to look up at his own, which my eyes search, trying to determine whether there is any truth in his words. Then I reach up to kiss him, my eyes offering an unspoken invitation, and this time, he doesn’t hesitate. This time, our lives outside of this moment are buried and forgotten.

Jack’s hands move down to the front of my dress, expert fingers removing me from it, revealing the black lace of my bra underneath. He lifts me onto the desk, knocking the room-service menu and hotel phone to the floor. Before I know what is happening, he’s on top of me, pinning my arms down, forcing his body between my legs.

‘And, cut,’ says the director. ‘Thanks, guys, I think we got it.’

Eight (#ulink_fd6dac2a-4baf-5380-9f58-57fd6a2702be)

Galway, 1987

Maggie held my hand all the way back to the cottage on the seafront. She held it so tight that it hurt a little bit some of the time. I think she was just afraid I might run away again, and that a bad person might find me like she said. But the only running I did was to keep up with her walking. She’s a fast walker and I’m tired now. She kept looking around the whole time, as though she was scared, but we didn’t pass any other people at all along the back streets, good or bad.

The cottage is very pretty, just like Maggie. It has a smart blue door and white bricks – it’s nothing like our house at home. She doesn’t have much stuff, and when I ask why not, she says this is just a holiday cottage. I’ve never been on holiday, so that’s why I didn’t know about things like that. She’s busy putting clothes in a suitcase now, and just when I think she might call the police, she decides to make us some tea and a snack instead, which is nice. On the walk here I told her all about how my brother said we can’t afford to eat, so she probably thinks I’m hungry.

‘Would you like a slice of gingerbread cake?’ she asks from the little kitchen. I’m sitting in the biggest armchair I’ve ever seen. I had to climb it just to sit on it, like a mountain made of cushions.

‘Yes,’ I say, feeling pleased with myself, sitting in the nice chair about to eat cake with the nice lady.

She appears in the doorway. The smile that was always on her face before, has vanished.

‘Yes, what?’

I don’t know what she means at first, but then I have an idea. ‘Yes, please?’ Her smile comes back and I am glad.

She puts the cake down in front of me, along with a glass of milk, then puts on the television for me to watch while she goes to use the phone in the other room. I thought she had forgotten about calling the police, and now I feel sad. I like it here, and I want to stay a bit longer. I can’t hear what she is saying over the noise of Zig and Zag on the TV – she’s turned the volume up very loud. When I’ve finished the cake I lick my fingers, then I drink the milk. It tastes chalky but I’m thirsty, so I finish the whole glass anyway.

I feel sleepy when she comes back in the room.

‘Now then, I’ve spoken to your daddy, and I’m afraid he says that what your brother told you is true: there isn’t enough food for you at home any more. I don’t want you to start your worrying again, so I’ve said to your daddy that you can stay here with me for a few days, and then I’ll take you back home once he’s sorted himself out. Does that sound grand?’

I think about the TV, and the cake, and the comfy chair. I think it might be nice to stay here for a little while, even though I will miss my brother a lot and my daddy a bit.

‘Yes,’ I say.

‘Yes, what?’

‘Yes . . . please . . . and thank you.’

It’s only when she leaves the room again that I wonder how she spoke to my daddy when we don’t have a phone at home.

Nine (#ulink_c4024be8-e8f0-58de-8bdf-e108faf8c826)

London, 2017

I check my phone again before getting out of the car. I’ve tried to call my agent three times now, but it just keeps going to voicemail. I even called the office, but his assistant said Tony was unavailable, and she used that tone people reserve for when they know something you don’t. Or perhaps I’m just being paranoid. With everything else that is happening, I suppose that’s possible. I’ll try again tomorrow.

The house is in complete darkness as I trudge up the path. I keep thinking about Jack and the way he kissed me on set. It felt so . . . real. I wear the idea of him like a blanket and it makes me feel safe and warm, the cloak of fantasy always more reliable than cold reality. But lust is only ever a temporary cure for loneliness. I close the front door behind me, leaving longing back in the shadows, out on the street. I switch on the lights of real life, finding them a little bright; they permit me to see more than I want to. The house is too quiet and too empty, like a discarded shell.

My husband is still gone.

I’m instantly dragged back in time, reliving the precise moment when his jealousy climaxed and my patience expired, generating the perfect marital storm.

I remember what he did to me. I remember everything that happened that night.

It’s a strange feeling, when buried memories float to the surface without warning. Like having all the air sucked out of your lungs, then being dropped from a great height; the perpetual sense of falling combined with the unavoidable knowledge that you’re going to hit something hard.

I feel colder than I did a moment ago.

The silence seems to have grown louder, and I look around, my eyes frantically searching the empty space.

I feel like I’m being watched.

The sensation you get when someone is staring at you is inexplicable, but also very real. I feel frozen to the spot at first, trying, but failing, to reassure myself that it’s just my imagination. Then adrenaline ignites my fight or flight response, and I hurry around the house, pulling all the curtains and blinds, as though they are fabric shields. Better safe than spied on.

The stalker first entered my life a couple of years ago, not long after Ben and I got together. It started with emails, but then she appeared outside our old house a few times, and delivered a series of hand-written cards when she thought nobody was home. Someone broke in when I was away in LA, and Ben was convinced it was her. It was one of the main reasons I agreed to move here, to a house I hadn’t even seen, except online. Ben took care of everything, so that we could get away from her. What if she found me? Found us?

The stalker always wrote the same thing:

I know who you are.

I always pretended not to know what that meant.

I feel lost. I don’t know what to do, how to feel, or how to act.

Should I call the police again? Ask for an update and tell them the things I didn’t last time, or just sit here and wait? You can never really predict how you will behave when life goes non-linear; you don’t know until it happens to you. People are capable of all kinds of surprising things. I’m dealing with the situation as best I can, without letting others down any more than I already have. I know I must be missing something, not just my husband, but I don’t know what. What I do know, is that the only person I can rely on to get me through this, is me. I don’t have anyone left to hold my hand. The thought triggers a memory, and my mind rewinds to when I was a little girl; someone always liked to hold my hand back then.

Something very bad happened when I was a child.

I’ve never spoken about it with anyone, even after all these years; some secrets should never be shared. The series of childhood doctors I was made to see afterwards said that I had something called transient global amnesia. They explained that my brain had blocked out certain memories, because it deemed them too stressful or upsetting to remember, and that the condition would most likely stay with me for life. I was just a child, and I didn’t take their diagnosis too seriously back then. I knew that I had only been pretending not to remember what happened. I haven’t given it too much thought in recent years. Until now.

I think I would remember if I had emptied and closed our bank account. I think a lot of things; the problem is that I don’t know.

I keep thinking about the stalker.

I can’t seem to stop my mind replaying the first time I saw her with my own eyes, standing outside our old home. I heard the letter box rattle and thought it was the postman. It wasn’t. A lonely-looking vintage postcard was face down on the doormat. There was no stamp. It had been hand-delivered, and I remember picking it up, my hands trembling as I read the then-familiar spidery black handwriting scrawled across the back.

I know who you are.

I opened the door and she was right there, standing across the street looking back at me. I thought I was going to throw up. I’d never seen her before, Ben had, but until that moment she was still little more than a phantom to me. A ghost I didn’t believe in. The previous emails, and then postcards, hadn’t scared me too much. But seeing her in the flesh was terrifying, because I thought I recognised her. She was some distance away, her face mostly covered with a scarf and sunglasses, but she was dressed just like me, and in that moment, I thought it was her. It wasn’t. It can’t have been.

She ran away when she saw me. Ben came home early and we called the police.

I should be more worried than I am about my husband.

What is wrong with me? Am I losing my mind?

It feels as if something very bad is happening again, something a lot worse than before.

Ten (#ulink_1a90c737-ecbb-51ee-a0cb-469f9d462440)

Galway, 1987

I feel lost when I wake up. I don’t know where I am.

It’s dark and cold. I have a tummy ache and feel a bit sick, just like I do when my brother takes me out on Daddy’s fishing boat. I reach out into the darkness, my fingers expecting to meet my bedroom wall, or the little side table made out of driftwood from the bay, but my fingers don’t feel that. Instead they touch something cold, like metal, all around me. I start to panic, but I’m very tired, so tired I realise that I must be dreaming. I close my eyes and decide that if I still don’t know where I am when I’ve counted to fifty inside my head, then I’ll let myself cry. The last number I remember counting is forty-eight.

The next time I open my eyes, I’m in the back of a car. It’s not my father’s car, I know that without having to think about it too much, because we don’t have one any more. He sold it to pay the electricity bill when the lights went out. The seats of the car I’m in are made of red leather, and my face and arms seem to be stuck to it when I first wake up; I have to peel them off.

I stare at the back of the head of the person driving, before remembering the nice lady called Maggie. Then I sit up properly and look out of the windows, but I still don’t know where I am.

‘Where are we going?’ I rub the sleep from my eyes, gifts the sandman left behind scratching my cheeks.

‘Just a little drive,’ says Maggie, smiling at me in the small mirror which shows a rectangle of her face.

‘Are you taking me back to my daddy’s house?’

‘You’re staying with me for a wee while, do you remember? There isn’t enough food for you at your house just now.’

I do remember her saying that, I’m just so tired I forgot.

‘Why don’t you have another little sleep, not far to go now. I’ll wake you when we get where we’re going. I have a lovely surprise for you when we get there.’

I lie back down on the red leather seat and close my eyes, but I don’t sleep. Even though I do like surprises, I’m scared and excited all at once. Maggie seems nice, but everything I just saw out the window looked so strange: the houses, the walls, even the signs on the side of the road.

I might be wrong, but it feels like I am a long way from home.

Eleven (#ulink_4e654f35-3e96-50be-a028-2a584db32a6c)

London, 2017