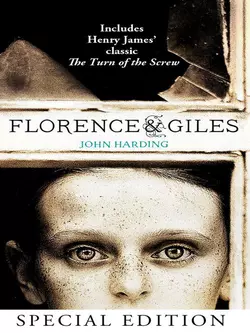

Florence and Giles and The Turn of the Screw

John Harding

A sinister Gothic tale in the tradition of The Woman in Black and The Fall of the House of Usher1891. In a remote and crumbling New England mansion, 12-year-old orphan Florence is neglected by her guardian uncle and banned from reading. Left to her own devices she devours books in secret and talks to herself - and narrates this, her story - in a unique language of her own invention. By night, she sleepwalks the corridors like one of the old house's many ghosts and is troubled by a recurrent dream in which a mysterious woman appears to threaten her younger brother Giles. Sometimes Florence doesn't sleepwalk at all, but simply pretends to so she can roam at will and search the house for clues to her own baffling past.After the sudden violent death of the children's first governess, a second teacher, Miss Taylor, arrives, and immediately strange phenomena begin to occur. Florence becomes convinced that the new governess is a vengeful and malevolent spirit who means to do Giles harm. Against this powerful supernatural enemy, and without any adult to whom she can turn for help, Florence must use all her intelligence and ingenuity to both protect her little brother and preserve her private world.Inspired by and in the tradition of Henry James' s The Turn of the Screw, Florence & Giles is a gripping gothic page-turner told in a startlingly different and wonderfully captivating narrative voice.

Florence & Giles

John Harding

For Norah

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#ue410808c-4644-5fd2-8607-2623fe145fc8)

Title Page (#u0e24d316-bd6c-5f77-a60e-7966582310c0)

Dedication (#uc5d35160-11d2-5214-accc-9262a42adb12)

The Swan (#u1ea4c3f0-9476-5838-9a06-0ddf103c67ef)

Part One (#ude60fca2-5d7e-5c22-9cbc-b0588bb1f6a6)

1 (#u687fca84-3f9d-5a84-9f42-a9adce1df580)

2 (#u683c13c0-36ce-52eb-977c-0d47bf888945)

3 (#uaa07a734-59bc-581f-93d5-5f5079e594d2)

4 (#u60405a4d-e1d7-5286-95f1-62725229cc76)

5 (#ue9e2776b-6806-5a81-830a-6cefc00a58b2)

6 (#uc41b2bc8-3a88-59af-8dd4-775a89d9976e)

7 (#ub8f04774-72d5-5ea7-8565-879990d7f9a8)

8 (#u5df8af7a-41bc-5e5c-83a9-e8e1e010de60)

9 (#u819f527c-e05e-5c66-b393-e1161bd6a4e0)

Part Two (#u461c7725-1820-5ae9-b05e-af127a01e393)

10 (#u915d3937-963d-5571-a3a5-b772ad230ac1)

11 (#u8115df85-c055-5b86-a2ae-cabf76f688f3)

12 (#uef1c42cd-8cb1-5ad0-af03-4c8fc584bd17)

13 (#ua92ad5d4-0fa8-5c08-9808-f5c12bb0b7bd)

14 (#ue887cb4c-6d37-5420-8040-33c0f46980e3)

15 (#litres_trial_promo)

16 (#litres_trial_promo)

17 (#litres_trial_promo)

18 (#litres_trial_promo)

19 (#litres_trial_promo)

20 (#litres_trial_promo)

21 (#litres_trial_promo)

22 (#litres_trial_promo)

23 (#litres_trial_promo)

24 (#litres_trial_promo)

25 (#litres_trial_promo)

26 (#litres_trial_promo)

27 (#litres_trial_promo)

28 (#litres_trial_promo)

29 (#litres_trial_promo)

30 (#litres_trial_promo)

31 (#litres_trial_promo)

32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by John Harding (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

The Swan (#ulink_1d96d17c-f5a6-5854-ad48-19174d63467b)

It was April, I remember, though my spirit was December,

When a broken bird was lifted from the darkness of the lake,

In the sun white feathers gleaming, from her mouth black water streaming,

While within my voice was screaming until I thought my heart would break;

It was I who watched her dying, drifting, drifting, waiting in her wake

For God her soul to take.

PART ONE (#ulink_2e540fbe-debf-586c-b33c-c0e387f4cca8)

1 (#ulink_ac75b4aa-4d71-5719-9fe8-ad17c150b9a1)

It is a curious story I have to tell, one not easily absorbed and understood, so it is fortunate I have the words for the task. If I say so myself, who probably shouldn’t, for a girl my age I am very well worded. Exceeding well worded, to speak plain. But because of the strict views of my uncle regarding the education of females, I have hidden my eloquence, under-a-bushelled it, and kept any but the simplest forms of expression bridewelled within my brain. Such concealment has become my habit and began on account of my fear, my very great fear, that were I to speak as I think, it would be obvious I had been at the books and the library would be banned. And, as I explained to poor Miss Whitaker (it was shortly before she tragicked upon the lake), that was a thing I did not think I could bear.

Blithe House is a great barn, a crusty stone mansion of many rooms, so immense it takes my little brother, Giles, who is as fast of limb as he is not of wit, three minutes and more to run through its length, a house uncomfortabled and shabbied by prudence, a neglect of a place, tightly pursed (my absent uncle having lost interest in it), leaked and rotted and mothed and rusted, coldly draughted, dim lit and crawled with dark corners, so that, even though I have lived here all of my life that I can remember, sometimes, especially on a winter’s eve in the fadery of twilight, it shivers me quite.

Blithe is two-hearted, one warm, one cold; one bright, the other shadowy even on the sunniest of days. The kitchen, where the stove is always burny hot, is jollied by fat Meg, our cook, smiley and elbowed in flour, often to be found flirted by John, the manservant, who seeks a kiss but is happy to make do with a floury smack. Next door, with a roaring fire nine months of the year, is the housekeeper’s sitting room, where you may find Mrs Grouse either armchaired and sewing or desked with a puzzlery of papers, trying, as she says, to ‘make head nor tail’ of things and – what seems to me contradictory – to make their ends meet. These two rooms together make one heart, the warm.

The cold heart (but not for me! Ah, not for me!) beats at the other end of the house. Unloved and unvisited, save by me, the library could not be more unlike the kitchen: unfired, cool even in the burnery of summer, freezing in winter, windows darked by never-opened thick drapes, so I have to steal candles to read there and afterward scrape their guilty drippery from the floor. From one end to the other is one hundred and four of my shoed feet, and thirty-seven wide. Three men could stand one upon the other and scarce touch the ceiling. Every inch of wall, aside from the door, the draped windows and their window seats, is wooden shelving, from floor to ceiling, all fully booked.

No maid ever ventures here; the floors are left unbroomed, for unfootfalled as they are, what would be the point? The shelves go unfingerprinted, the wheeled ladders to the upper ones unmoved, the books upon them yearning for an opening, the whole place a dustery of disregard.

It has always been so (apart from the governessed times, of which more anon), leastways as far as I remember, for I first made my way here a third of my lifetime ago, when I was eight. We were then still ungovernessed, because Giles, who is some three years my junior, the one the teaching’s for, was considered too young for school or indeed any kind of learning, and we were hide-and-seeking one day when I opened a strange door, one that hitherto had always been locked – or so I had thought, probably on account of its stiffness, which my younger self could not manage – to refuge from him there, and discovered this great treasury of words. The game was straightway forgotten; I shelf-to-shelfed, extracting book after book, the opening of each a sneezery of dust. Of course I could not then read, yet that somehow wondered me even more, all these thousands – millions more like – of coded lines of undecipherable print. Many books were illustrated, woodcutted and colour-plated, a frustratory of captions beneath, every one of which taught me the miserable impotence of finger-tracery.

Later, after I had been scolded for going missing for so long that Mrs Grouse had everyone searching for me, not only all the maids but floury Meg and John too, I asked her if she would teach me to read. I instincted not to mention the library and it feared me quite when she gave me a quizzical look and said, ‘Now missy, what in the world has made you think of that?’

It was one of those questions it’s best not to answer, for if you keep quiet, grown-ups will always go on to something else; they lack the persistence of children. She deep-breathed in and long-sighed it out. ‘The truth is, Miss Florence, that I’m not exactly sure your uncle would want that. He has made clear to me his views on the education of young women. I think he would say that this was not the time.’

‘But please, Mrs Grouse, he wouldn’t have to know. I wouldn’t tell a soul and if he should visit unexpectedly I would hide my book behind my back and stuff it under the cushions of the chair. You could teach me in your sitting room; even the servants need not know.’

She laughed and then serioused again. She lined her brow. ‘I’m sorry, Miss Florence, I wish I could, I really do, but it’s more than my job’s worth.’ She got her mouth into a smile, something it was always ready to do. ‘But I tell you what, there’s a little housekeeping left this month, maybe enough for a new doll. Now, young lady, what say you to a new doll?’

I said yes to the doll; it was better to appear bought off, but her refusal to help me, far from discouraging me, opposited, and merely stubborned my resolve. Slowly, and with some difficulty, I taught myself to read. I lingered the kitchen and stole letters from John when he was reading the newspaper. I would point to an ‘s’ or a ‘b’ and ask him to tell me its sound. One day in the library I fortuned upon a child’s primer and from that and from here and there, I eventually broke the code.

So began the sneakery of my life. In those early days Giles and I were let wild; much of the day we could play as we liked. We had only two restrictions: one was to avoid the old well, although that was anyway covered up with planks and paving slabs too heavy for us to lift and so was just one of those things grown-ups like to worry themselves about and presented no danger to us at all; the other was to stay away from the lake, which was exceeding deep in parts, and perhaps might. How like grown-ups it is to see danger where there is none; to look for it in a lake or a well, which offer no harm in themselves without the agency of human malevolence or neglect. Yet these same cautious adults would be all unaware when the threat to us children actually came, for unlike us, for all their talk of the house being full of ghosts and ghouls, they had long ago ceased to hear unexplained footsteps in the dark.

Running apart, my brother Giles has not many talents, but one thing he is good at is keeping a secret. When I took him to the library, he little cared for the books, although he could be occupied by colour plates of birds or butterflies for an hour or two. He was happy enough scampering up and down the ladders and climbing the shelves or hiding behind the drapes, or else he would play outside; you could trust him, even at that early age, to avoid the lake, or Mrs Grouse’s prying eyes.

I, meanwhile, spent hour after hour reading, and because my absences, although unremarked during the daytime, would be noticed in the evenings, my bedroom became a smugglery of books. After Giles reached the age of eight and was sent away to school, of course, my life turned into an unheedery of anyone else. I could come and go as I liked; this part of the house was largely unvisited, and I grew so bold I scarce worried about anyone seeing me enter or leave the library, or disturbing the dust that lived there. In this way I absorbed Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, the novels of Sir Walter Scott, Jane Austen, Dickens, Trollope, George Eliot, the poetry of Longfellow, Whitman, Keats, Wordsworth and Coleridge, the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, they were all there. But one writer towered them all. Shakespeare, of course. I started with Romeo and Juliet, moved on to the histories, and soon made short work of the rest. I wept for King Lear, I feared Othello, and dreaded Macbeth; Hamlet I simply adored. The sonnets weeped me. Above all, I fell in love with the iambic pentameter, a strange passion for an eleven-year-old girl.

The thing I liked most about Shakespeare was his free and easy way with words. It seemed that if there wasn’t a word for what he wanted to say, he simply made one up. He barded the language. For making up words, he knocks any other writer dead. When I am grown and a writer myself, as I know I shall be, I intend to Shakespeare a few words of my own. I am already practising now.

It was always my greatest ambition to see Shakespeare on stage, but there is no theatre between here and New York City, hopelessing my wish. Last summer, not long before Giles was sent off to school, the people who have the estate next door, the Van Hoosiers, came calling; they had a son, Theodore, a couple of years older than me, an only child they wished to unbore. They lived in New York most of the year, travelling the hundred miles or so up here only in summer to escape the heat of the city, and the young man had no one to keep him amused and so he excited to find me. He sat and doe-eyed me all through tea.

Afterward Mrs Grouse suggested I show Theodore the lake. Now it misfortuned that Giles was ill in bed that day, confined by a severe headache. My brother is as sickly as I am well; he has illness enough for us both, while I have no time to be indisposed, having all the looking after and worrying to do. Giles’s absence now, when young Van Hoosier and I outdoorsed, gave my visitor free rein with me. He nuisanced me, obsessed as he was by my allowing him to give me a kiss. I had no fixed objection to this, being, as I was, not much younger than Juliet when she got herself romanced, but young Van Hoosier was no Romeo. He had a large head and eyes like balls that stood out from their sockets. He looked like a giant bug. Now, I am tall for my age, but Theodore was even taller, without half as much flesh; he beanpoled above me, which did not endear him to me, for I have never been one who could stand to be looked down upon.

We were side-by-siding on a stone bench beside the lake and I shifted myself to other-end from him, for I found his attentions annoying and was about ready to get up and leave, but then he let slip, no doubt at some mention of mine of Shakespeare, that he had seen Hamlet. I alerted and sat up straight and looked at him anew. Perhaps, after all, this boy might not be so unbooked as he succeeded so well in appearing; there were possibilities here, I sensed. I offered him a deal. I would allow him the kiss he so craved, if he would write a love poem for me.

Well, he pulled out a notebook and pencil and got right down to it there and then, and in no time at all was ripping out the page he’d written on and handing it to me, which impressed me quite, though I dare say you can guess what befell. Foolish girl, I wanted him to summer’s day me, I really thought he might. Instead, of course, he doggerelled me and, after he’d forced the kiss he claimed was his due, left me crying by the lake, not only roughly kissed but badly Longfellowed too. Here is how the Van Hoosier ode finished, so you’ll understand for yourself:

What fellow who has any sense

Would not want to kiss Florence?

2 (#ulink_f955c710-be7b-5b99-8f91-d42ebcb2b695)

Giles was sent away to school last fall when he was eight, which, although young, was in keeping with other boys of his class who lived in remote places such as Blithe, where there was no suitable local school. We horse-and-trapped him to the station, John and Mrs Grouse and I, to put him on the train to New York, where he was to be met by teachers from the school. We cried him there; at least Mrs Grouse and I did, while John losing-battled with a quivering lower lip. Giles himself was happy and laughing. He could not remember ever having been on a train and, in his simple, childlike way, futured no further than that. Once on board, he sat in his seat, windowing us with smiles and waves, and I bit my lip and did my best to smile him back, but it was a hard act and I was glad when at last the train began to move and he vanished in a cloud of steam.

I berefted my way home. All our lives, Giles and I had never been apart; it was as though I had lost a limb. How would he fare unprotected by me, who understood his shortcomings so well and loved him for them? Although I had no experience of boys apart from Giles and the silly Van Hoosier boy, I knew from my reading how they cruelled one another, especially at boarding schools. The idea of my little Giles being Flashmanned weeped me all over again when I had just gotten myself back under control. When we neared Blithe House and the trap turned off the road into the long drive, avenued by its mighty oaks rooked with nests, it heavied my heart; I did not know how my new, amputated life was to be borne.

Most girls my age and situation in life would long have been governessed, but I understood this was not for me. By careful quizzery of Mrs Grouse, and a hint or two dropped by John, and general eavesdroppery of servantile gossip, I piecemealed the reason why. My uncle, who had been handsome as a young man, as you could see in the picture in oils of him that hung at the turn of the main staircase, had at one time been married, or if not actually wed, then engaged to, or at least deeply in love with, a young woman, a state of affairs that lasted a number of years. The young lady was dazzlingly beautiful but not his equal in refinement and education, although at first that seemed not to matter. All futured well until she took it into her head (or rather had it put there by my uncle) that she beneathed him in intellectual and cultural things; their life together would be enriched, it was decided, if they could share not just love, but matters of the mind. The young lady duly enrolled in a number of courses at a college in New York City.

Well, you can guess what happened. She wasn’t there long before she got herself booked, and musicked and poetried and theatred and philosophied and all ideaed up, and pretty soon she offrailed, and most probably started drinking and smoking and doing all sorts of other dark deeds, and the upshot of it was that she ended up considering she’d overtaken my uncle and intellectually down-nosing him, and of course then it was inevitable but that she someone-elsed. At least, I think that’s what happened, although I misremember now how much of the above I eavesdropped and how much my mind just made up, as it is wont to do.

And so my uncle took against the education of women. He pretty much decultured himself too, far as I can tell. He shut up Blithe House and left the library to moulder and moved to New York, where I could not imagine he could have had so many books. I had no idea how he passed his time without books, for I had never met him, but I somehow pictured him big-armchaired, brandied and cigared, blank eyes staring out of his once handsome, but now tragically ruined, face into space and thinking about how education had done for his girl and blighted his life.

So I lonelied my way round the big house, opening doors and disturbing the dust in unslept bedrooms. Sometimes I would stretch myself out on a bed and imagine myself the person who had once slumbered there. Thus I peopled the house with their ghosts, phantomed a whole family, and, when I heard unidentified sounds in the attic above me, would not countenance the idea of mice, but saw a small girl, such as I must once have been, whom I imagined in a white frock with a pale face to match, balleting herself lightly across the bare boards.

The thought of this little girl, whom I began to believe might be real, for Blithe was a house abandoned by people and ripe for ghosts, would always eventually recall me to the games I had played with Giles. To unweep me, I would practical myself and search for new places to hide for when he should return at the end of the semester, and when that staled, which it did with increasing frequency, I libraried myself, buried me in that cold heart that more and more had become my real home.

One morning I settled myself down with – I remember it so well – The Mysteries of Udolpho, and after two or three hours, as I thought, I’d near ended it when I awared a sound outside the window, a man’s voice calling. Now, this was an unusual occurrence at Blithe, any human voice outdoors, for there was only John who worked outside and he had not, as I have, the habit of talking with himself, and everywhere was especially quiet now with Giles gone and our sometimes noisy games interrupted, so that I ought to have been surprised and to have immediately investigated, but so absorbed was I in my gothic tale, that the noise failed to curious me, but rather irritated me instead. Eventually the voice began to distant, until it died altogether or was blown away by the autumn wind that was gathering strength outside. I had relished a few more pages when I heard footsteps, more than one person’s, growing louder, coming toward me, and more shouting, but this time inside, followed by a flurry of feet in the passage outside, and the voice of Mary, the maid, calling, ‘Miss Florence! Miss Florence!’ And then the door of the library was flung open followed by Mary again calling my name.

I froze. As luck would have it I was ensconced in a large wingbacked chair, its back to the door, invisibling me from any who stood there, providing, of course, they no-furthered into the room. My heart bounced in my chest. If I were discovered it would be my life’s end. No more books.

Then Meg’s voice, ‘She’s not here, you silly ninny. What would she be doing in here? The girl can’t read. She’s never been let to.’

I muttered a prayer that they wouldn’t notice the many books whose spines I had fingerprinted, my footsteps on the dusty floor.

‘Well, that’s as maybe,’ replied Mary, ‘but she’s got to be somewhere.’

The sound of the door closing.

The sound of Florence exhaling. I closed the book carefully and made sure to put it back in its place upon the shelf. I crept to the door, put my ear to it and listened. No sound. Quick and quiet as a mouse, I opened the door, outed, closed it behind me, and sped along the passage to put as much distance as possible between me and my sanctum before I was found. As I made my way to the kitchen I wondered what all the to-do was about. Obviously something had happened that required me at once.

I could hear voices in the drawing room as I tiptoed past and went into the kitchen, where I interrupted Meg and young Mary, who were having an animated chat. At the sound of the door they stopped talking and looked up at me in a mixture of surprise and relief.

‘Oh, thank goodness, there you are, Miss Florence,’ said Meg, deflouring her arm with a swishery of kitchen cloth. ‘Have you any idea what the time is, young lady?’ She nodded her head at the big clock that hangs on the wall opposite the stove and my eyes followed hers to gaze at its face. It claimed the hour as five after three.

‘B-but that’s impossible,’ I muttered. ‘The clock must be wrong. It cannot have gotten so late.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with the clock, missy,’ snapped Meg. ‘Begging your pardon, miss, it’s you that’s wrong. You’re surely going to catch it from Mrs Grouse, you’ve had the whole household worried sick. Where on earth were you?’

Before I could answer I heard footsteps behind me and turned and face-to-faced with Mrs Grouse.

‘M-Mrs Grouse, I – I’m sorry…’ I stammered, and then stopped. Her face, rosy-cheeked with its Mississippi delta of broken veins and their tributaries, was arranged in a big smile.

‘Never mind that, now, my dear,’ she said kindly. ‘You have a visitor.’

She turned and went into the passage. I rooted to the spot. A visitor! Who could it possibly be? I didn’t know anyone. Except, of course, my uncle! I had never met him and knew little about him except that, according to his portrait, he was very handsome, the which would be endorsed by Miss Whitaker when she arrived.

Mrs Grouse paused in the passageway and turned back to me. ‘Well, come along, miss, you mustn’t keep him waiting.’

Him! So it was my uncle! Now perhaps I could ask him all the things I wanted to ask. About my parents, of whom Mrs Grouse claimed to know nothing, for she and all the servants had come to Blithe only after they had died. About my education. Perhaps when he saw me in the flesh, a real, living young lady rather than a name in a letter, he would relent and allow me a governess, or at least books. Perhaps I could charm him and make him see I wasn’t at all like her, the woman who had been cultured away.

Mrs Grouse stopped at the entrance to the drawing room and waved me ahead of her. I heard a cough from within. It made me want to cough myself. I entered nervously and stopped dead.

‘Theo Van Hoosier! What are you doing here? Shouldn’t you be at school?’

‘Asthma,’ he said, apologetically. Then triumphantly, ‘I have asthma!’

‘I – I don’t understand.’

He walked over to me and smiled. ‘I have asthma. I’ve been sent home from school. My mother has brought me up here to recuperate. She thinks I’ll be better off here in the country, with the clean air.’

Mrs Grouse bustled into the room. ‘Isn’t that just grand, Miss Florence. I knew you’d be pleased.’ She dropped a nod to Theo. ‘Not that you have asthma, of course, Mr Van Hoosier, but that you’ll be able to visit us. Miss Florence has been so miserable since Master Giles went off to school, moping around the house on her own. You’ll be company for one another.’

‘I can call on you every day,’ said Theo. ‘If you’ll permit me, of course.’

‘I – I’m not sure about that,’ I mumbled. ‘I may be…busy.’

‘Busy, Miss Florence,’ said Mrs Grouse. ‘Why, whatever have you to be busy with? You don’t even know how to sew.’

‘So does that mean I may, then?’ said Theo. He puppied me a smile. ‘May I call on you, please?’ He stood holding his hat in his hand, fiddling with the brim. I wanted to spit in his eye but that was out of the question.

I nodded. ‘I guess, but only after luncheon.’

‘That’s dandy!’ he said and immediately got himself into a coughing fit, which went on for some time until he pulled from his jacket pocket a little metal bottle with a rubber bulb attached, like a perfume spray. He pointed the top of the bottle at his face and squeezed the bulb, jetting a fine mist into his open mouth, which seemed to quieten the cough.

I curioused a glance at him and then at the bottle.

‘Tulsi and ma huang,’ he said. ‘It’s an invention of your Dr Bradley here.’

I puzzled him one.

‘The former is extracted from the leaves of the Holy Basil plant, the latter a Chinese herb long used to treat asthma. It is Dr Bradley’s great idea to put them together in liquid form and to spray them into the throat for quick absorption. He is experimenting with it and I am his first subject. It appears to work.’

There followed an awkward silence as Theo slowly absorbed that the subject had not the interest for me that it had for him. Then, in repocketing the bottle, he managed to drop his hat and as he and Mrs Grouse both went to pick it up they banged heads and that started him off coughing and wheezing all over again. Finally, when he had stopped coughing and had his hat to fiddle with once more, he gave me a weak smile and said, ‘May I visit with you now, then? After all, it is after luncheon.’

‘It may be after yours,’ I said, ‘but it ain’t after mine. I haven’t had my luncheon today.’ And I turned and swept from the room with as much poise as I could muster, hoping that in getting rid of Theo, I hadn’t jumped it back into Mrs Grouse’s mind about me going missing earlier on.

3 (#ulink_d94e9800-8a65-5c3f-aba8-c059a72634da)

Suddenly my existence was uncosied. I was seriously problemed. First I had to make sure I didn’t fail to show up for a meal again, lest next time they went looking for me they find me, with all the repercussions that would involve. But the question was easier posed than solved. I had no timepiece. Then over a late luncheon, when Mrs Grouse was so full of Theo Van Hoosier she didn’t think to interrogate me as to my whereabouts earlier, I pictured me something about the library that might undifficulty me regarding my problem and, as soon as I’d finished eating, slipped off and made my way there.

Sure enough, tucked away in a dark corner, mute and unnoticed, was a grandfather clock. It was big, taller than I, though not nearly so tall as Theo Van Hoosier, the prospect of whose daily visits almost unthrilled me of the finding of the clock. Gingerly I opened the case, as I had seen John do with other clocks in the house, and felt about for the key. At first I thought I was to be unfortuned, but then as I empty-handed from the case there was a tinkle as my little finger touched something hanging from a tiny hook and there was the key. I inserted it in the hole in the face and began winding, being careful to stop when I met resistance, for John had warned me that overwinding had been the death of many a timepiece.

I had noted the time when leaving the kitchen and to be safe added fifteen minutes on to that to allow for my getting to the library and for the finding of the key. The clock had a satisfyingly loud tick and I thought how at last I would no longer feel alone here. There would be me, my books and something akin to another heartbeat, if only in its regularity. Something, moreover, that wasn’t Theo Van Hoosier.

Of course, no sooner did the starting of the clock end one problem than it began another. For if anyone should venture into the library its ticking was so loud they could not fail to notice it and so be set to wondering who had started it and kept it wound and then on to working out who had been here. I shrugged the threat away. So be it. I had to know the time during my sojourns here or I would be discovered anyway. Besides, no one else had ever been in here in all my librarying years, so it unlikelied anyone would now. Too bad if they did; it was a risk I had to take.

That afternoon it colded and our first snow of the fall fell. I watched it gleefully, hoping it would mean that Theo Van Hoosier would not be able to visit. Surely if his asthma was enough to keep him from school he should not be trudging through snow with it? I kept my fingers crossed and imagined him asthmaed up at home, consoling himself with a bad verse or two.

With this promise of salvation, though, the snow difficulted me in another way. Or rather the drop in temperature did. I had never wintered much in the library, because it had no fire and colded there, and because before I always had Giles to keep me amused elsewhere. Although I tried gamely, determined reader that I am, to carry on there, my fingers were so cold I could scarce hold my book or turn its pages, let alone keep my numbed mind on it. I slipped out of the room and by means of the back staircase made my way to the floor above. There I found a bedroom whose stripped bed was quilted only in dust, but footing it was an oak linen chest in which were three thick blankets. Of course, there was riskery in transporting these to the library, because if I encountered anyone en route I would be completely unexplained. And unlike a book, I could not simply slip a bulky blanket inside my dress.

Nevertheless, without the blankets I would not be able to read anyway, so it had to be done. I resolved to take all three at once since one would be just as hard to conceal as three and the fewer blanketed trips I made, the lower the risk. They were a heavy and awkward burden, the three together piled so high I could scarce see over them, but I outed the room and pulled the door shut after me with a skill of foot-flickery. I had halfwayed down the back stairs and was about to make the turn in them when I heard the unmistakable creak of a foot on the bottom step of the flight below. I near dropped my load. It was no good turning and running, one way or another I would be caught. There was nothing for it but to stand and await my fate. I held my breath, listening for another step below. It never came. Instead I heard Mary’s voice, talking to herself (ah, I thought, so I am not the only one who does that!). ‘Now where did I put the darned thing? I made sure it was in my pocket. Damnation, I shall have to go back for it.’

I heard a slight grateful groan as the stair released her foot and then angry footsteps hurrying along the corridor below. I waited a moment after their sound had faded away, then scurried down, tore along the passage and ducked through the library door.

There I pushed together two of the big leather wingbacked armchairs, toe to toe, and nested me in them with two of the blankets for a bed and the third stretched over the tops of the chair backs to make a canopy. I thought of it as my own four-poster, though of course it had nary a single one. When I left the room I pushed apart the chairs again, folded the blankets and hid them behind a chaise longue. It might offchance that someone entering the room would just not notice the clock, or attach the correct significance to it if they did, clocks being an ever present in many rooms and an often unnoticed background kind of thing. But they could not fail to see my nest and so it had to be constructed every day anew.

Thus began a new pattern to my days. The mornings I tick-tocked away in my nest, contenting me over my books until the clock struck the quarter hour before one, when I denested, slipped from the room and hurried to lunch. But soon as Theo Van Hoosier began to call, the afternoons problemed me anew. I had no way of knowing what time he might arrive and despite my best efforts to schedule him he proved as unreliable as he was tall. Sometimes he appeared directly after lunch; others he turned up as late as half past four. He excused himself on the grounds that he had a tutor and was dependent upon the whimmery of same.

Now, suppose I went to the library and young Van Hoosier came while I was there, it would be as bad as the time I missed lunch. They would search for me and either my secret would be discovered or later they would question it out of me. On the other hand, if I hung around in the drawing room or the kitchen waiting for Theo and he arrived late, I could waste hours of precious reading time.

That is what I was forced to do, the first few Van Hoosier days. I sat in a twiddlery of thumbs looking out the window at the snow or playing solitaire. The worst thing was my idleness attentioned me to Mrs Grouse and set her to wondering why she had not noticed it before; she didn’t guess how I had always out-of-sighted-out-of-minded me, and it started her talking about me doing something useful, such as learning to sew. She even sat me down one day and began to mystify me with stitchery. I thought I would lose my mind.

I have read somewhere that boredom mothers great ideas and so it was with me. Where I was going wrong was in my association of reading with the library, whereas in fact all I needed was somewhere I could private myself and from where I could keep an eye on the front drive to see the approach of Theo Van Hoosier. No sooner had I thought of this than I solutioned it. Blithe House had two towers, one at the end of either wing. They were mock gothic, all crenellations, like ancient fortresses, and neither was at all used any more. I suspect they were never made much of, since each had its own separate staircase, its upper floors reachable only from the ground, so that to go from the room on the second floor to one on the same floor in the neighbouring part of the house, you first had to descend the tower stairs to the first floor, go to one of the staircases leading to the rest of the house and then ascend again. But what the towers promised to offer was a commanding view of the drive. From the uppermost room, of either, I guessed, I would be able to see all its curvy length. The function of the towers had always been decorative rather than practical, and the one on the west wing had been out-of-bounded to Giles and me because it was in need of repair, which naturally, with my uncle’s tight pursery, never came. Therefore I could be sure that no one would ever go there. If I could get to it unobserved, I would be able to read whilst looking up from time to time to observe the drive. Moreover, the west tower had another great convenience: it was only a short corridor and a staircase away from the library, a necessary proximity, because I would have to carry books up there.

Consequently, the following afternoon, armed with a couple of books in readiness for an afternoon of reading and Van Hoosier spotting, I duly set off for the west tower, only to be met by the most awful hope-dashery at the foot of its stairs. In all my plotting there was something I had quite forgot. Placed across the bottom of the stairs, nailed to the newel post, were several thick boards, floorboards no less, completely blocking any ascent, put there, like the planks and stone slabs over the well, to prevent Giles and me from dreadful accidenting. I set down my books and tried to move the planks, but they were firmly fixed, so I only splintered a finger for my trouble; no budgery was to be had. I was in a weepery of frustration. I tried putting my feet on one board to clamber over, but there was no foothold for it, access was totally denied. Besides, I realised, even if I had been able to climb over, any entry so arduous and difficult would be so slow I’d be laying myself open to redhandery should anyone chance that way.

I picked up my books and had started to walk away, utterly disconsolate at the loss of my afternoons just when I thought to have recovered them, when I brained an idea. I dashed back, went around the side of the staircase, pushed my books through one of the gaps between the banisters, then hoisted myself up and found I could climb the stairs from the outside, by putting my feet in the gaps. In this way I was able to ascend past the barricade and then, thanks to my leg-lengthery, haul myself over the banister rail and onto the staircase. I stood and looked down with satisfaction at the barrier below and felt how safe and secure I would be in my new domain. I certained no one else would be able to follow me. I couldn’t imagine Mary or fat Meg or plump Mrs Grouse stretching a leg over the banister rail, even if they had been witted enough to think of it.

I made my way up to the second floor, then to the third and finally through a trapdoor to the fourth, the uppermost, from which I could look down upon not only the driveway but also the roof of the main building. The top of the tower consisted of a single room, windowed on all sides. I stood there now, mistress of all I surveyed, fairytaled in my tower, Rapunzelled above all my known world. I looked around my new kingdom. It was sparsely furnished and appeared to have been at one time a study. There was a chaise and a heavy leather-topped keyhole desk, the leather itself tooled with a fine layer of mould, and before the desk, a revolving captain’s chair. It was heads or tails whether the library or this room contained more dust and I would not have liked to wager upon it. The windows were leaded lights and a few of the small panes were missing, so a fine draught blew through the room and there were bird droppings on the dusty floor, showing that the wind was not the only thing that entered this way.

Still, it was all a wonder to me. The windows had drapes at the four corners but these were all tied back and I realised I would have to be careful and keep my head low so as not to be visible from below. No matter, if I sat at the desk, I could Van Hoosier the drive and so long as I did not move about excessively no one was likely to see me.

The ventilation of the missing panes meant the room would always be cold and my first task was to secure more blanketry. I set down my books and duly went scavenging. It tedioused having to go right down to the first floor and then up again to the second for my purloinery but there was no other way. I had emptied my old chest of blankets for the library and I did not fortune upon another such. However, I did find a couple of guest bedrooms that were kept in readiness should we ever have another guest and I to-the-winded my caution, stripped them of their quilts, stole two of the three blankets beneath and then replaced the quilts. I surveyed what I had done. I had skinnied the beds but I couldn’t imagine anyone would notice, and should a maid remake the bed she probably wouldn’t suspect. After all, who at Blithe – other than a shivering ghost – would steal a blanket?

I made sure the coast was clear and sped down the staircase to the first floor, along the main corridor, and threw the blankets over the barrier at the bottom of the tower stairs. I had just hauled myself up onto the outside of the stairs when the door to the main corridor opened. No time to wait! I hurled myself head over toe over banister rail and onto the stairs, where I crouched behind the barricade, hoping for unseenery through the gaps.

‘Oh my goodness, what was that!’ It was Mary’s voice.

‘Ghosts most likely,’ said a voice I recognised as belonging to Meg. ‘They say Blithe is full of ghosts.’

‘Tch! You don’t believe in that nonsense, do you?’ Mary’s voice betrayed a certain lack of confidence in the words it uttered.

I spyholed them through the barricade. Meg raised an eyebrow. ‘I reckon I’ve worked here five years and seen many things. When you’ve been here as long as I have, you’ll know, you’ll know.’ And she opened the door to the main corridor again, picking up a dustpan into which she’d evidently just swept something. She disappeared inside; before Mary followed her, she pulled a face at the older woman’s retreating back.

So here I was, princessed in my tower, blanketed at my desk, shivering some when the wind blew, but alone and able to read, at least until it twilighted, because I could have no giveaway candles here. I suddened a twinge, thinking – I knew not why just then – of Giles, away at his school, in turn thinking perhaps of me, and I wondered if he was happy. It brought to mind how I had once torn in two a playing card – the queen of spades it was – straight across the middle, thinking to make two queens from one, the picture at the top and its mirror image below, but found instead I did not even have one, the separate parts useless on their own, and it struck me this was me without Giles, who was a part of my own person. How I longed for his holidays to begin so I could show him our new kingdom. This was all I lacked for happiness, for Giles to be here to share it with me.

It was not to be. And so I started off on my new life. I morninged in the library and afternooned in my tower. I reasoned early on that it would be foolish to keep returning books to the library after finishing my day in the tower; carrying them about increased the likelihood of being caught. This meant that if I were reading something in the morning, I could not continue with the same book in the afternoon. I resolved therefore to make a smugglery of books in the tower (where there was little chance of detection anyway), which would remain there until they were finished, and for my reading day to be of two separate parts. I libraried the mornings away on solid books, philosophy, history and the like; I also began to teach myself languages and to work up a passable knowledge of French, Italian, Latin and Greek, although I would not vouch for my accent in the two former, never having heard either of them spoke; the afternoons were my fantasy time, appropriate for my tower. I indulged myself in Mrs Radcliffe, ancient myths and Edgar Allan Poe. The only fly in my ointment here, though, was that I must never let my concentration lapse, must never surrender myself too much to the words that swam before my eyes and in my head and distract myself to my doom.

On the day after I first occupied my tower, I morninged out up the drive, measuring how long it would take Theo Van Hoosier to walk its length, from the moment he first visibled from the tower, to the moment when he vanished from view under the front porch of the house. How did I work out the time, I who had no timepiece? I counted it out, second by second, and to make sure my seconds were all the right length I figured them thus: one Shakespeare, two Shakespeare, three Shakespeare. In this way I reckoned that young Van Hoosier would be in view for four and a half minutes. Thus, when I set out for the tower room after lunch I would first sneak into the drawing room, which has a direct view of the drive, and make sure Van Hoosier was not in view. If he was not, then I had four and a half minutes to get to the tower, otherwise, if I took any longer and he should appear unviewed at the precise moment my back was turned when I set off, he could have reached the front door and be out of view again before I was at my post and so occasion all the dangerous calling and searching for me. Let me tell you, it was a stretch to make it to the tower in that time. If I happened to meet John or Mary or Meg or Mrs Grouse and they delayed me for even a few seconds it impossibled my journey in the allotted time and so meant I had to go back and check the drive and start once more from the beginning. Not only that, all the while I had to be one-Shakespearing-two-Shakespearing and if someone should speak to me and I should lose my number, then it was back to the drawing board – that is the drawing room – all over again.

By the time I reached the bottom of the tower staircase I was usually up to two hundred-Shakespeare and it was touch and go whether I could climb the outside of the staircase, haul myself over the banisters, take off my shoes (for fear of my running feet booming out on the uncarpeted treads) and get to the tower room in time. On one occasion I just made it, peeped through the window and saw Van Hoosier’s hat disappearing under the front porch, so that I had to tear back down the staircase, haul myself back over the banisters, climb down the outside bit and get myself into the main corridor all over again before they started hollering for me. But then, no one had ever told me having a secret life was going to be easy.

4 (#ulink_92fe9f5f-158e-56c4-a9fc-dcece82c946e)

That first day when it snowed I figured myself likely weather-proofed against the Van Hoosier boy, but I had made the very mistake that all too many people made with me (who would have thought I had two book nests? who would have thought I Frenched and Shakespeared?), namely I judged him by appearances. I figured him a spineless sort of tall weed, who would buckle in two without his starched shirt to hold him upright. So I grudged an admiration for him that day when I upglanced the drive from the drawing room (I had not then found my tower refuge, of course) and saw him Wenceslasing his way through the drifted snow. A dogged and doglike devotion to me, I realised, worth so much more than his doggerel could ever be.

Mrs Grouse told me to wait in the drawing room. I heard her open the front door and invite him to shake the snow from his boots, followed by an interval of quite prodigious stamping. Shortly afterward, the door to the drawing room opened and Mrs Grouse said, ‘Young Mr Van Hoosier to see you, miss,’ as though we didn’t both know I was sitting in there waiting for him and as if, too, I were much used to visitory. In this, and in adjectiving our guest as young, Mrs Grouse showed that she herself didn’t know how to behave, that she was a housekeeper and childminder, not a hostess. When she shut the door behind him, I noticed she had even neglected to relieve Van Hoosier of his hat.

I invited him to sit down. I had positioned myself in an armchair so as to preclude any possibility of him nexting me and he couched himself opposite, folding himself as though he were hinged at the knees and hips. We sat and smiled politely at one another. I did not know what to do with him and he did not know what to do with his hat. He sat and Gargeried it, twisting it this way and that, rotating it with one hand through the thumb and forefinger of the other, flipping it over and over. Finally, after he’d dropped it for the third time, I upped and overed to him. I irritabled out a hand. ‘Please, may I take that?’

He gratefulled it to me. I outed to the hall and hung it with his coat. But when we were seated again I realised I might have removed the hat but I had not removed the problem. Indeed I had exacerbated it, for now he had nothing to fiddle with. He was forced to fall back on cracking his knuckles, or crossing and uncrossing his legs, this way and that. I hard-stared his shins and he caught my gaze and, uncrossing his legs, put both feet firmly on the floor. He looked scolded and in that moment his face so Gilesed I twinged guilt.

‘Well,’ he said at last, ‘here we are.’

‘It would appear so,’ I frosted back.

‘It is very cold outside. The snow is deep.’

‘And crisp and even,’ I said.

‘What?’ He knew he was being made fun of, but could not quite figure out how.

We sat in silence some moments more. Then he said, ‘Oh yes, I almost forgot,’ and began patting the different pockets of his jacket and pants in an unconvincery of unknowing the whereabouts of something. Finally he pulled out a folded paper and began to unfold it. ‘I wrote you another poem.’

The look I gave him was several degrees colder than the snow and like enough to have sent him scuttling back out into it. ‘Oh no, it’s OK; you don’t have to entertain a kiss this time. There’s no question of any kissing being involved.’

I thawed my face and settled back in my chair. ‘Well, in that case, Mr Van Hoosier, fire away.’

Well, the least said about the second Van Hoosier verse, the better. The best you could say was that it was nowhere near as bad as the first, especially as it didn’t carry the threat of a kiss, although, then again, I wasn’t too impressed by the final rhyme of ‘immense’ and ‘Florence’; fortunately the reference was to the supposed number of my admirers, not my size.

When he’d finished reading it, Theo looked up from the paper and saw my expression. ‘Still not the thing, huh?’

‘Not quite,’ I said.

He crumpled the paper into a ball and thrust it into his pocket. ‘Darn it,’ he said good-naturedly, ‘but I’ll keep going at it till I crack it, you see if I don’t. I’m not one for giving up.’

In this last he proved as good as his word, not just in the versifying but in the snow trudgery too. It didn’t matter if it blizzarded, or galed or howled like the end of the world outside, he Blithed it every afternoon for the next couple of weeks. After he’d visited with me a few times I began to see that, like his verse, his lanky body rhymed awkwardly and scanned badly. His long limbs didn’t fit too easily into a drawing room, where it seemed one or other of them was always flailing out of its own accord, tipping a little side table here or tripping a rug there; he was like a huge epileptic heron. It impossibled to comfortable him indoors, so on the fourth or fifth visit, when he suggested we take ourselves outside, I was somewhat relieved, for if we stayed in it was only a matter of time before china got broke; not that I minded that, for there was nothing of value at Blithe and no one to care about it anyhow, but I could imagine how distraught he would be. It was only as we put on our coats that I second-thoughted. Was it really safe to have him clumsying about on snow and ice? Would not his parents blame me if it were one of his arms or legs, rather than china, that got broke? God knows, there was enough of them to damage.

‘Is this wise?’ I said, as he mufflered himself up.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, your asthma and all. Taking it out into the cold.’

‘Not at all. It’s the best thing for it, a nice bright frosty day like today when the air is dry and clear. It’s the damp dreary days that get on my chest and set me to coughing.’

So out we went and, to my surprise, my very great surprise, we funned it for a couple of hours. It was not that Theo lost his awkwardness in this new element, but rather that this element was so bare and empty of obstacles that he had nothing to do but fall over on the ice, which he did time and time again. When he went you had to stand clear as his great arms windmilled fit to knock your head off if you should happen to put it in the way of them and his legs jerked up like a marionette’s and then everything collapsed like a deckchair and left a dead spidery bundle on the ground. It was so comical that the first time I burst out laughing before I could help myself and then, when the pile of his bones didn’t move, rushed to him, fearfulling what I would find. But he always pulled himself up with a smile and so after a while we got to making snowballs and throwing them at one another, at which he took a terrible pasting because his own throws were so bad he was as like to hit himself as put one on me. And then he suggested we make a snowman, and we started but we had only got halfway through fashioning a sizeable head when it reminded me of the winter before, how I’d done this with Giles, and it guilted me. I thought of him classroomed somewhere while I was still here enjoying myself and not thinking of him for a single moment for two whole hours together, and all at once I was chilled to my core and couldn’t unchatter my teeth, so that Theo, seeing this, insisted we repair indoors.

As if my thoughts had either been stirred by those of Giles himself or themselves stirred him, next day there was a letter from him. He was not a great correspondent, lacking as he did my facility with the written word, although I had done my best to teach him to read and write. Mrs Grouse, who totally ignoranted this, of course, thought it a marvel how quickly the school had taught him to write, although his letters were so badly formed it took me a great while to figure out even this short epistle. Before I had the letter to myself, though, I had to listen to Mrs Grouse’s guesses as to what Giles’s mangled hieroglyphics might mean, for, of course, I was not supposed to be able to read them for myself. The poor woman, who was, I suspected, as literate, or rather illiterate, as my brother himself, could make a fair fist of only three-quarters of it and more or less guessed the rest. But when I had it to myself, I managed by long study, and knowledge of Giles, to pretty much figure it out.

Dear Flo,

I am to write home every other Sunday. We have a time for it and all the boys must do it. I hope you are well. I hope Mrs Grouse is well. I hope Meg and Mary and John are all well. I am very well thank you. I am not homesick. I am very slow with my lessons but I don’t mind. The other boys laugh at me for this, but I don’t mind the laughing so much. I will close now.

Your loving brother

Giles

What did it mean, ‘I don’t mind the laughing so much’? So much as what? Were there other things that he minded more, physical intimidation perhaps, some kind of pinching or hitting or hair-tugging or fire-roasting? Or was it merely a figure of speech, a way of saying he wasn’t greatly bothered by it? And why did he talk about not being homesick? Why mention it at all, unless perhaps he was and had been instructed not to worry those at home by writing them about it. The letter weeped me and that night in bed I puzzled over it again, then pillowed it, wanting thereby to feel close to poor Giles.

5 (#ulink_e796571a-2b28-5b1b-92a7-394f5688f198)

You should not deduce from that afternoon in the snow with Theo Van Hoosier that I was all joy unalloyed at his visits. There was plenty to alloy my joy, but nothing more so than the disturbance to my reading. It was not simply the long and often untimely interruptions the visits occasioned. It was also all the moments when he unappeared. You will recall that whenever I was towered I had to check the drive once every four and a half minutes. To leave margin for error this meant once every four minutes. But, of course, I was untimepieced and I didn’t see myself hauling no grandfather clock over the banisters and up the stairs. The only way I could judge the time, therefore, was by the turn of my pages, the pace at which I read. So before taking each book from the library I timed myself reading a few pages by the grandfather clock, to determine exactly how far four minutes would take me. If it were three and a half pages, then up in the tower room I would have to look out the window at every such interval. I cannot begin to tell you how annoying this was. It was like trying not to drop off to sleep; all the time, as the book drew me in, as its author surrounded me with a whole new world, some part of me was fighting the delicious surrender to such absorption and saying, three and a half, three and a half, three and a half. Sometimes I’d sudden I’d forgotten, that seven or eight pages, or even ten or fourteen, had passed with no looking up. When that occurred I had no way of knowing whether Van Hoosier had all unseen upped the drive during my relapse, and so there was nothing for it but to down book and clamber all the way down the stairs, and run along the corridor to check out the hall and drawing room and then, if they were un Hoosiered, upglance the drive, and if that were likewise Theo-free, make the mad dash up to the tower again. On a good book such as Jane Eyre I might be up-and-downstairsing four or five times in an afternoon.

One day in the tower, I lifted my eyes from my book, resenting this crazy, jerky four-minute way of reading and, through the window, saw a rook pecking at something in the snow. The scene was the perfect picture of a new state of mind I realised I had reached. The perfect white snow, the black rook a nasty stain upon a newly laundered sheet; for the first time I understood that there was nothing wholly good and nothing wholly bad, that every page has some blot, and, by the same token, I hoped, every dark night some distant tiny shining light. This hoped me some. The rook on my landscape was Giles, and all the suffering he might be going through, and all the suffering I endured from the great hole inside of me where he should have been. But the rook was one small black dot and the rest was all white. Did that not offer the prospect that most of my brother’s school life might be happy and carefree, with perhaps one or two small things he did not like? And yet, why had he mentioned not being homesick, except to reassure me? What could it mean but that he was?

Anyway, there were the Christmas holidays to look forward to when Giles would be home and I would be able to worm the truth from him, although what good that would do me I couldn’t be sure. Meanwhile I read all the mornings and some of the afternoons and then Van Hoosiered my way through the rest. Because of his restless and wayward limbs and the need to keep them from fine china, Theo was always up for getting out in the snow. One day I looked out my tower window and saw a bent figure trudging up the drive and almost went back to my book, for I thought it must be some delivery man and could not be he. This fellow appeared to be a hunchback with a great lump on his spine, but it fortuned me to watch him a bit longer and then the hump moved, leapt off his back and dangled from one of his hands and the rest of the shape organised itself into the unmistakable gangle of Theo and I was off, leaping the banisters and racing the corridor.

In the hall Theo opened the leather bag he was carrying with a flourish like a magician dehatting a rabbit. ‘What…?’ I cried.

‘Skates. Well, you have a lake out back, don’t you?’

Mrs Grouse was all concern. Suppose the ice crust was too thin and broke and we fell through it and drowned? What would she say to Theo’s mother then? I thought that seeking to concern us about her social difficulty rather than our own deaths was the wrong way to go with this argument, but I held my peace. Of course, nobody was worried about what to tell my mother. And significantly Mrs Grouse hadn’t mentioned any possible embarrassment with my uncle, for we both knew he would mourn such an event as a disencumbrance.

John fortuned at this point to be passing through the hallway on some errand and to overhear and intervene. He assured Mrs Grouse that he had skated on lakes in these parts every winter as a boy and that at this time of year the ice was at least a foot thick. He undertook to accompany us out there and, at Mrs Grouse’s insistence, check the lake’s surface very carefully ‘lest there be any cracks’, which caused John to roll his eyes and smile behind her back.

To my great surprise, especially after his previous slipping and sliding on the snow around the house, Theo proved to be an accomplished skater. Once he had those skates on he was transformed. From an early age, he’d had plenty of practice every year in Central Park, and was able to zoom around the lake at great speed, to turn and spin and glide, every movement smooth and graceful. He minded me of a swan, which is ungainly as a walker, waddling from side to side, and awkward as a flier, struggling to get off the ground and into the air, and then making a great difficulty of staying up there, but which on the water serenes and glides. I guess it was a great relief to Theo to be out on the frozen lake with nothing to collide with, no delicate side tables and fine china out to get him, no rug-trippery to untranquil his progress.

By contrast I hopelessed the task. My legs were determined to set off in opposite directions, my head had an affinity with the ice and wanted to keep a nodding acquaintance with it, my backside had sedentary intentions. But Theo kinded me and helped me; he was a different person, taking control, instructing me, commanding me as I commanded him on unvarnished land. And gradually, over a period of a couple of weeks, I began to improve, so that soon I was going a whole ten minutes without butting or buttocking the ice.

So it was that each afternoon I found myself looking up every page or so, instead of four-minuting, for I longed to see Theo upping the drive. And then, one day, he didn’t come at all. I was reading The Monk, making the hairs on my neck stand on end, shivering myself in the dead silence of the tower, when I looked up anxiousing for Theo and realised I could scarce see the drive, as the light was fading fast; I was still able to read, for my tower, being the highest and westernmost point of Blithe, is where the sun lingers longest. I put down my book and downstairsed. What could have happened to Theo? Why had he not come? True, it had snowed mightily that morning, but that had never put him off before. Had his tutor forbidden his visits? Had he perhaps some new work schedule that disafternooned him?

I found Mrs Grouse in the kitchen. ‘Where have you been?’ she demanded crossly, adding before I could answer, ‘A note has come for you,’ and she produced an envelope that she opened, taking out the single sheet inside and unfolding it. She put on her spectacles and peered at it. ‘It’s from young Mr Van Hoosier,’ she said, and then began to read.

Dear Florence,

I am sorry I cannot come today. Asthma is my companion this afternoon. Doctor called, strenuous exercise forbidden. Please continue to skate and do a circuit or two for me.

The note ended with a poem:

To Florence I would make a trip

But asthma

Hasma

In its grip

I liked that. It wasn’t exactly Walt Whitman. But it was better, much better.

As she folded the note and handed it to me (although what she thought I, whom she supposed unable to read, could do with it, I do not know) Mrs Grouse said, ‘You must pay a visit to the Van Hoosiers, to ask after him. It’s what they would expect. It’s what a young lady should do.’

‘But…’ I was about to say I never visited anywhere, for I never had. Giles and I had never played with other children, for we knew none. This was one reason why I so concerned for him at school. But Giles leaving home and all the Theoing I’d had had changed all that. I saw that now.

‘Very well, I’ll go in the morning.’

And Mrs Grouse smiled and I could feel her eyes on my back as I walked off to the kitchen to ask Meg what sweet pastries she might have for me to take to Theo.

6 (#ulink_3cb3bed3-459d-5a62-ba8e-386c8a2a6b50)

I don’t know when the nightwalks started, for I had had them as long as I remembered, and of course, of the walks themselves I recalled nothing, except the waking-up afterward in strange places, for example the conservatory, and once in Mary’s room up in the attic, and several times in the kitchen. I knew, though, how the walks always began; it was with a dream, and the dream was every time the same.

In it I was in bed, just as I actually was, except that it was always the old nursery bedroom which was now Giles’s alone but which I used to share with him, until Mrs Grouse said I was getting to be quite the young lady and ought not to be in a room with my brother any longer. I would wake and moonlight would be streaming through the window – oftentimes, though far from always, the walks happened around the time of the full moon – and I would look up and see a shape bending over Giles’s bed. At first that was all it was, a shape, but gradually I realised it was a person, a woman, dressed all in black, a black travelling dress with a matching cloak and a hood. As I watched she put her arms around Giles and – he was always quite small in the dream – lifted him from the bed. Then the hood of her cloak always fell back and I would catch a glimpse of her face. She gazed at my brother’s sleeping face – for he never ever woke – and said, always the same words, ‘Ah, my dear, I could eat you!’ and indeed, her eyes had a hungry glint. At this moment in the dream I wanted to cry out but I never could. Something restricted my throat; it was as though an icy hand had its grip around it and I could scarce get my breath. Then the woman would gather her cloak around Giles and, as she did so, turn abruptly and seem to see me for the first time. She would quickly pull her hood back over her head and steal swiftly and silently from the room, taking my infant brother with her.

I would make to follow but it was as though I were bound to the bed. My body was leaded and it was only with a superhuman effort that I was finally able to lift my arms and legs. I would sit up and try to scream, to wake the household, but nothing would come, save for the merest sparrow squawk that died as soon as it touched my lips. I would put my feet to the floor, steady myself and walk slowly – my limbs would still not function as I wished them to, in spite of the urgency of the situation – to the doorway. There I would look in either direction along the corridor but have no clue which way the woman had gone. It was no good trying to reason things, she was as likely to have gone left as right and I was wasting valuable time prevaricating. And so I would choose right, it was always right, and begin to walk, urging my weighted legs to move. And then…and then…I would wake up, sitting on the piano stool in the drawing room, perhaps, or in Meg’s chair in the kitchen, sometimes alone but like as not surrounded by the servants, who would be watching me, making sure I did not have some accident and harm myself, or somehow get outside and drown myself in the lake. When I woke, my first words were always the same: ‘Giles, Giles, I have to save Giles.’ And Mrs Grouse or John or Meg or Mary, whoever was there, would always say, ‘It’s all right, Miss Florence, it was only a dream. Master Giles is safe and sound asleep.’

Because I remembered virtually nothing of the walking part of the dream what I knew of my nightwalking came from the observations of other people. Often I liked to nightwalk in the long gallery, a windowed corridor on the second floor that stretched along the central part of the front of the house. John told me how, when he first came to work at Blithe, he had been to the tavern in the village one Saturday night and was returning home up the drive somewhat the worse for wear when he looked up at the house and saw a pale figure, all in white, moving slowly along the long corridor, now visible through one window, then disappearing to reappear a moment later in the next. At the time he knew nothing of my nocturnal habits. ‘I don’t mind telling you, miss,’ he told me many a time, ‘I ain’t no Catholic but I crossed myself there and then. Knowing as I do the reputation Blithe has for ghosts, how it has always attracted and pulled them in, I convinced myself it was some evil spectre I was seeing. I was sure I’d come in and find the whole household murdered in their beds.’

Mrs Grouse told me that I always walked slowly, not as sleepwalkers are usually depicted in books, with their arms outstretched in front of them as if they were blind and feared a collision, but with my arms hanging limply at my sides. My posture was always very erect and I seemed to glide, with none of the jerkiness of normal walking, but smoothly, as if, as she put it, ‘you were on wheels.’

It was true what John said about Blithe and ghosts. Mrs Grouse reckoned it all stuff and nonsense but Meg once told me the local people thought it a place ghouls loved, a favourite haunt, as it were, to which any restless spirit was attracted like iron filings to a magnet. And now, even though it was only I, Florence, sleepwalking, I seemed somehow to have added to this superstition.

Meg told me that when I woke from my walks it uselessed to speak to me for several minutes, that I seemed not to hear. Often, before I was myself, at the moment when I seemed to have emerged from the dream but had not yet returned to real life, I began to weep and was quite distraught, and if any should try to comfort me I pushed them away and said, ‘No, no, don’t worry yourself about me! It’s Giles who needs help. We must find him, we must!’ Or something like.

After I had nightwalked three or four times and it began to be a pattern, they called in Dr Bradley, the local doctor, who came and gave me a good going-over, shining lights in my eyes and poking about in my ears and listening to my heart and so on. He pronounced me fit and well and told them it was likely the manifestation of some anxiety disorder, which was only natural considering my orphan status and the upheavals of my early life. This was confirmed, he said, by my fears focusing upon Giles, who was, after all, the only consistent presence in my life. I read all this in a report I found on Mrs Grouse’s desk one day, when she had gone into town on some errand. I curioused over the words ‘upheavals of my early life’. I could not remember anything of my parents – my mother died in childbirth and my father some four years later with my stepmother, Giles’s mother, in a boating accident. I recalled nothing of any of them, and as the servants were only engaged after they were all dead, they could tell me nothing either. As far as my early life went, it was all a blank, a white field of snow, without even the mark of a rook.

7 (#ulink_47510528-821a-5810-aaef-f22f4f0a4322)

Before I set out to visit the Van Hoosiers next morning, John came back from town with a letter, a rare enough occurrence at Blithe, where Mrs Grouse received correspondence from my uncle maybe two or three times a year and little else. It was for me, and I reflected that from being completely unlettered but a few weeks ago I was now the most episto-latoried person for miles around. The letter was, of course, from Giles and I heart-in-mouthed as Mrs Grouse commenced to read it, after she had first sniffed and said, ‘Humpf, seems folks think I’ve nothing better to do all day than read letters to you.’

Dear Flo,

Thank you for your letter. I have read it ever so many times and it is tearing from so much folding and unfolding. I like the sound of your ice skating and cannot wait for the holidays. Do you think Theo Van Hoosier will be able to find any skates to fit me? Will the ice bear the weight of three of us? Or will we take turns? I am very slow at my lessons, but I don’t mind when the others laugh at me. It is better than being hit or pinched. But you are not to worry about it because it does not happen often. Not so very often, anyway. I hope you are well. I hope Mrs Grouse and John are well. I hope Meg and Mary are well.

Your loving brother

Giles

The letter from me Giles referred to was, of course, written by Mrs Grouse and so contained none of the things I would have liked to tell him, about the tower room, for instance (although I had not yet decided whether or no to let him in on that), and none of the anxious inquiries about himself I longed to make. His references to pinching and hitting shivered me quite, although it uncleared whether he had actually suffered physical abuse or if ‘you are not to worry about it because it does not happen often’ merely referred to the teasing, but I had no time to reflect upon it now. I was all done up ready to go visiting, so I took the letter from Mrs Grouse and slipped it into my overcoat pocket, where it heavied my spirit as if it had been a convict’s leg iron or a hunk of stolen bread down a schoolboy’s pants. I had wanted to walk to the Van Hoosier place but Mrs Grouse would have none of it. It was more than a mile and although the roads were clear of snow today, if it blizzarded again I might be stranded halfway, not to mention that even if that didn’t happen I would death-of-cold me. She neverminded that I had been out in the cold on the ice every afternoon anyway. So John was to horse-and-trap me there, which was fine by me, for once we out-of-sighted Blithe and Mrs Grouse’s prying eyes he handed me the reins and let me drive, as he often did when the housekeeper wasn’t around. The old horse we used on the trap, Bluebird, was so docile and knew all the local routes so well that in truth there was not much driving to be done, and even should it snow, it little dangered the horse leaving the road and wandering into a ditch.

I had never seen the Van Hoosier place; it was approached by a long driveway, and set in woodland so far back from the main road as to invisible all but its chimneys when we drove past. So I was surprised to find it smaller than Blithe, although in every other respect much grander. You could tell that from the moment you turned off the road and through the entrance gates, which were newly painted, in contrast to our own peeling and chipped portals. The edges of the drive were neatly manicured and the lawns either side trimmed to within an inch of their lives. The house itself sparkled and gleamed in the winter sun; it did not absorb the light like dull old Blithe. John dropped me at the front door. ‘I’ll drive the trap around the back and make myself comfortable in the servants’ kitchen, Miss Florence,’ he said as he handed me down. ‘Just have them send for me when you’re ready to leave.’

I anxioused as I reached for the bell pull. I was all best-frocked today and did not feel in my own skin. The door was opened (soundlessly, it did not creak like nearly all the doors at Blithe) by a uniformed footman. ‘Yes, ma’am,’ he said, questioning an eyebrow.

‘I – I came to inquire after the health of Mr Van Hoosier,’ I mumbled. ‘That is, I mean, well, young Mr Van Hoosier.’

‘And you would be…?’

‘Florence, from Blithe House.’

He held open the door and bowed me in. I found myself in a grand hallway with a great sweeping staircase, chandeliered and crystalled to the nines, mirrors everywhere, so that I was surrounded by what seemed dozens of pale, gawky girls, staring at me from all directions. ‘If you’ll just wait one moment, miss, I’ll tell Mrs Van Hoosier you’re here.’

He went off, heels clicking the tiled floor. I gazed at myself in the mirrors some more then decided to concentrate on looking down at my boots, which I found far more comfortable. After what seemed an age – I figured he had a mighty long way to walk – the man clicked his way back and invited me to follow him. He led me down a long corridor, opened a door and insinuated me into a small sitting room, where Mrs Van Hoosier was seated at a walnut writing desk, evidently in the middle of penning a letter. She looked up and sugared me a smile. ‘Come in, my dear, come in and make yourself comfy. You must be frozen after your journey over here.’

She stood up, walked round the desk and shook my hand. I handed her the paper bag of pastries I had brought. ‘For Theo,’ I explained.

She opened the bag and peered at its contents and then, without comment, placed it on the desk and indicated a chair by the fire. ‘Melville, bring us some coffee and cake, would you?’ I heard the door close behind me. I sat down. I had met Mrs Van Hoosier but the once, the time they called at Blithe to introduce us to Theo. I had little attentioned her on that occasion, being much more taken with Theo and wondering how long it would be before he broke something. Observing her now, what struck me most was what a huge battleship of a woman she was. She was tall, and you could see that was where Theo got his height from, but she was also filled out, solid, not bendy like her boy. She was mantelpieced by a large bosom that cantilevered out in front of her; you could have stood things on it, a vase of flowers and a bust of Beethoven, and a family photograph or two, maybe. Her hair was all piled up on her head and that probably added another few inches. When I sat down she gianted over me, which didn’t help my nervousness.

She put one hand on the mantelpiece over the fire and leaned against it.

‘I – I came to inquire after Theo, I mean Mr Van Hoosier,’ I muttered. ‘I was hoping perhaps to visit with him and maybe cheer him up.’

She insincered me a smile. It felt like a grimace. ‘Ah yes, how kind of you, but I’m afraid that won’t be possible. He’s much too sick. The doctor has forbidden him any excitement.’

I smiled at the thought that I might constitute excitement.

‘You find that amusing?’

‘Oh, no, ma’am, not at all. It was just, well…’ My words died away.

The door opened and Melville reappeared with a tray. Mrs Van Hoosier sat down on the opposite side of the fireplace from me. Melville moved a side table next to her and set the tray on it. He placed another table beside me. ‘That’s all right, Melville, you can go.’