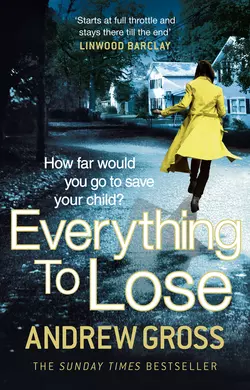

Everything to Lose

Andrew Gross

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Триллеры

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 467.61 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The heart-pounding new thriller from the co-author of five No. 1 James Patterson bestsellers including Judge and Jury and Lifeguard, and the Sunday Times bestsellers The Blue Zone and Reckless.WHEN YOU HAVE EVERYTHING TO LOSEYOU STOP PLAYING BY THE RULESHilary Cantor’s life is falling apart. She has lost her job, is about to lose her house, and is running out of money to care for her young son with Asperger’s syndrome.But when Hilary is first on the scene of a fatal car accident, she finds a satchel full of cash on the backseat – enough to solve all of her problems. Her split-second decision has devastating consequences…Because the money she takes is at the heart of a conspiracy involving murder, blackmail and a powerful figure who’ll do anything to keep the past buried. They don’t just want their money back: they want Hilary’s life – and that of her son…