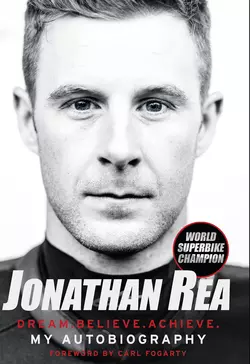

Dream. Believe. Achieve. My Autobiography

Jonathan Rea

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Хобби, увлечения

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1552.59 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘If I had to lose my record to anyone, I couldn’t be happier that it was Jonathan. Family connections aside, there is nobody more talented, more determined or more deserving.’ – Carl FogartyWithin the staggeringly dangerous and high-pressure sport of professional motorcycling, Jonathan Rea’s achievements are unprecedented. A legendary World Superbike Champion withmore race wins than any rider in history, Rea’s trailblazing success shows no sign of slowing down.Now, for the first time, this remarkable sportsman tracks his life and career. Seemingly destined for the racing world, Jonathan grew up in the paddocks – his grandfather was the first sponsor of five-times World Champion Joey Dunlop and his dad was a former Isle of Man TT winner. He owned his first bike before his hands were big enough to reach the brakes.But while racing may be in his blood, it is through sheer determination and relentless perseverance that Rea has gained huge victories in this ultra-competitive world. Topping several of the most prestigious motorcycling championships, he rules the sport – so much so that regulations are being introduced to curb his dominance. The fact that Rea has endured several potentially career-ending scrapes – including smashing his femur at the age of seventeen and being told that he would never race again – makes his achievements even more incredible.‘Dream. Believe. Achieve,’ is Rea’s mantra and in this gripping autobiography, we go behind the visor and into the mind of a man who has risen to the top of one of the most skilled and dangerous sports in the world.