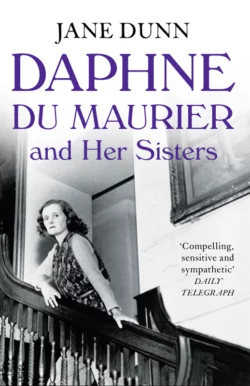

Daphne du Maurier and her Sisters

Jane Dunn

The Du Mauriers – three beautiful, successful and rebellious sisters, whose lives were bound in a family drama that inspired Angela and Daphne’s best novels. Much has been written about Daphne but here the hidden lives of the sisters are revealed in a riveting group biography.The middle sister in a celebrated artistic dynasty, Daphne du Maurier is one of the master storytellers of our time, author of ‘Rebecca’, ‘Jamaica Inn’ and ‘My Cousin Rachel’. Her success and fame were enhanced by films of her novels and horrifying short stories, ‘Don’t Look Now’ and the unforgettable ‘The Birds’ among them. But this fame overshadowed her sisters Angela and Jeanne, a writer and an artist of talent, living quiet lives even more unconventional than Daphne’s own.In this group biography they are considered side by side, as they were in life, three sisters brought up in the hothouse of a theatrical family with a peculiar and powerful father. This family dynamic reveals the hidden lives of Piffy, Bird & Bing, full of social non-conformity, creative energy and compulsive make-believe, their lives as psychologically complex as a Daphne du Maurier plotline.

DAPHNE

DU MAURIER

AND HER SISTERS

The Hidden Lives of

Piffy, Bird and Bing

JANE DUNN

Dedication

In celebration of all sisters,

and particularly mine:

Kari, Izzy, B, Trish and Sue

(and our outnumbered brothers Marko and Andy)

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE (#u05d40d9c-e8d1-5f2c-9a59-1e29ea4f5faf)

DEDICATION (#u4865493b-3545-5e15-8eaf-ea6f85f60a13)

DU MAURIER FAMILY TREE (#u63f8ae32-afde-52ae-ba68-ef671d39b4b8)

PREFACE (#u25ab24ea-b529-51f5-9f30-24b48a0bba4d)

1. The Curtain Rises (#ubd6b8e09-b7d6-57a0-b24f-b0dfab7725cc)

2. Lessons in Disguise (#u39f135da-37ab-57c9-9deb-59e9456e6d92)

3. The Dancing Years (#u093f090c-17bb-5e31-951d-f0a4c6c7e7ee)

4. Love and Losing (#u935a95f3-9ef5-5f9b-ad40-427ff271e8d0)

5. In Pursuit of Happiness (#ud7ada9fb-1ce1-5727-8272-ea63af597b4b)

6. Set on Adventure (#u60a1431a-4f59-51c6-813c-3b1eb826c4be)

7. Stepping Out (#ud00d161d-e076-5ed8-83d0-cb13fd1c32a6)

8. A Transfiguring Flame (#u2a45e8b6-b21e-5f69-919c-94e0831098eb)

9. Fruits of War (#ubc5904e1-b316-5ae1-9d63-e07a94ecb7b1)

10. A Mind in Flight (#u676335cf-727d-5e06-ba3c-22c1730354f6)

11. A Kind of Reckoning (#u06ecfaf4-c50a-5cc8-ac2a-8e007fdc1044)

12. Heading for Home (#u5e553a98-63d3-53ce-835f-7edd1f88c2c5)

AFTERWORD (#ub76da621-c540-59e8-a03a-9068b6f22037)

PICTURE SECTION (#u2cb5b2d5-7cf2-5b2f-a7d1-f7c0cd6c673e)

FOOTNOTES (#ua53df4f5-499c-5003-8713-f59e829aaf29)

NOTES (#uf4d4d3bf-9390-50d2-81d1-e4adc894e037)

ILLUSTRATIONS (#u3e3a1514-e13d-57bb-998e-7d0ebd2ac003)

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY (#u85420c15-e034-50f6-8f48-06c754f38332)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u52804cdd-f59e-508c-9040-ae66de08540f)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#u7174257e-63d8-5f07-8251-cce3bcb46968)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR (#u5025c0f7-a813-56d1-81e0-6eca961a3223)

COPYRIGHT (#ua1d1c814-e0d3-59de-a8a5-a0d7c9757bb3)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#u3f8d2146-8ca3-53f0-9bbc-fc9b27d4ed1d)

DU MAURIER FAMILY TREE

PREFACE

But it is very foolish to ask questions about any young ladies – about any three sisters just grown up; for one knows, without being told, exactly what they are – all very accomplished and pleasing, and one very pretty. There is a beauty in every family. It is a regular thing. Two play on the piano-forte, and one on the harp – and all sing – Or would sing if they were taught – or sing all the better for not being taught – or something like it.

JANE AUSTEN, Mansfield Park

JANE AUSTEN UNDERSTOOD about sisters. Mansfield Park and Persuasion seethe with them. Pride and Prejudice is as much about the affection, rivalry and vexation of sisters as it is about the complicated progress of true love for Jane and Elizabeth with Bingley and Darcy. Jane Austen shared a bedroom with her elder sister Cassandra all her life and they relied entirely on each other’s love and support. There is something infinitely touching about their relationship, and tragic too, for Cassandra lived on alone for twenty-eight years after her younger sister died.

In biography, families are the soil out of which character grows, and one of the richest composts is the relationship of sisters. They are ever fascinating, cast from the same mould yet struggling for difference, brought up in the same family yet each with a childhood unique to herself. For good and ill, the sibling bond lasts a lifetime, longer than any other relationship with parents, partners or children, and it is sisters who weave the most complex webs of love and loyalty, resentment and hurt. Adults can turn sisters against each other by cruel comparisons and overt favouritism, as happened in the lifelong feud, continuing into their nineties, between the star of the film of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, Joan Fontaine, and her elder sister Olivia de Havilland, who landed the starring role in Daphne’s other great blockbuster, My Cousin Rachel. When sisters’ affections turn sour it can be deadly, for each knows the family’s secrets. More often, however, sisters are a foil and support to each other, a source of inspiration and close conspiracy; the safety net encouraging flight and breaking a fall.

Daphne du Maurier was fascinated by the Brontë siblings and identified with them all, but she jokingly hoped she and her sisters might emulate Charlotte, Emily and Anne one day, if only she could get her artist sister to write too. A bevy of sisters is more than the sum of its parts and it is to this protean relationship that I, as a biographer, like to turn. The first pair I explored was Virginia Woolf and her artist sister Vanessa Bell. This was an archetypal relationship of passionate dependence and rivalry, ultimately transfigured into self-sacrificing love, remarkably well delineated in the sisters’ own letters, Virginia’s novels and Vanessa’s portraits. I followed Virginia & Vanessa with other biographies that featured prominently sisters, daughters and female cousins. Then, with this book, another set of sisters drew my attention.

For most of my life I had been unaware that Daphne du Maurier, author of so many stories that had gripped my young self, had any sisters at all. To find that she had two, her elder sister Angela a writer like herself, and her younger, Jeanne, a painter, piqued my interest. To have a sister’s fame so eclipse the others was psychologically interesting. Even more intriguing, however, was to find how different were the characters and lives of all three du Maurier sisters, yet how strongly imprinted with family values, bonded to each other in their desire to live in close proximity in Cornwall – with Jeanne eventually settling over the border in Dartmoor.

In writing the story of Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf I had set out to try and convey, as far as possible, their lives and thoughts in their own words. I hoped to do the same with the du Maurier sisters and was gratified to find how many of Daphne’s letters existed, and how candid and full of interest they were. She had also written a memoir of herself when young, based on the early diaries that she subsequently embargoed. Daphne’s letters are so rich, expressive and funny that they rival Nancy Mitford’s for wit and brio. All three du Maurier sisters wrote excellent letters: conversational, lively with news and comment and a great deal of humour, but Angela’s and Jeanne’s have been largely destroyed or withheld.

Angela was a prolific writer of letters all her long life. She had many friends and acquaintances, but when she was old it seems that she wrote to her closest friends and asked them to destroy her letters. She had already burnt all her love letters, she explained to one of her past lovers, whose letters she had decided to keep. She also could not bring herself to burn her love poems to various important women in her life. For Angela, her deepest feelings and what made her happy in life, were in conflict with her desire to keep up appearances. She learnt early to dissemble to her parents. This conflict became more marked as she grew older, living within a close community in Fowey in Cornwall, where she was held in respect as ‘Miss Angela’, and attached to an Anglo-Catholic Church unsympathetic to any nonconformity in faith or life.

Despite this attempt to obscure her true self, two extrovert autobiographies, if read carefully, are full of hints of a larger life, a more independent and courageous attitude to love, than one might ever suspect from the conventional face she chose to present to the world. She did not want to be known for her guise as maiden aunt who had missed out on love. There had been much more to her than her Pekinese dogs and the roles of dutiful daughter, dependable friend and stalwart of Church and community. I hope this exploration of her life is in keeping with at least one aspect of her family’s ethos, for the sisters were much influenced by their own father’s view that a biography is only worth doing if it attempts to tell the truth without evasion or pretence. Daphne boldly followed this precept with her own memoir of her father, soon after his death, shocking some of his old friends with her temerity.

Whereas following Angela’s clues have led me on an intriguing journey of dead-ends and surprising revelations, the search for Jeanne has been blocked from the beginning of my researches. Her lifelong partner, the intellectual and prize-winning poet Noël Welch, still lives in their exquisite house on Dartmoor with the best collection of Jeanne’s paintings, all her papers and her memories. Now in her nineties, she has been adamantly set against any biography of the sisters, despite writing her own insightful piece on them for The Cornish Review nearly forty years ago. There are vivid glimpses of Jeanne in other people’s letters and memoirs. In the few letters that have surfaced, an expressive, amusing, highly creative voice rings out through the years as freshly as when they were written.

The du Maurier girls could not have been more closely brought up. They were consciously sheltered from the contamination of school; for them there was no escape where, freed from controlling adults, they might speak of taboo subjects like sex and God and money. Largely lacking outside friends, the sisters were thrown on each other’s company and their own imaginations in a way that seems peculiarly intense compared to modern childhoods, with the ready distractions of the wider world. Moreover, they never quite managed to cast off the bonds of their family: the tentacles of the past spread into every part of their adult lives. Their influence on each other as children was potent and undiluted and it both held them back and spurred them on. For this reason I have dwelt at some length on their shared early life at Cannon Hall in London’s Hampstead.

In this, the last generation to be named du Maurier, as daughter after daughter was born, it was hoped that at least one of them would have been a son, to ensure the continuation of the family genius and name. As mere girls, however, they would have to do as best they could. It was good indeed, but could it ever be good enough? The superlatives that surrounded their parents and forebears entered the romance of their family inheritance. ‘These things added to our arrogance as children,’ was how Daphne described the effect in her scintillating recreation of a theatrical childhood in her novel The Parasites: ‘as babies we heard the thunder of applause. We went about, from country to country, like little pages in the train of royalty; flattery hummed about us in the air, before us and within us was the continual excitement of success.’

Edwardian parental influence and du Maurier expectation was paramount. But given the distinctiveness of their upbringing, the sisters relied on each other for education and entertainment, with little change of view contributed by outside friends or adults who were not in the theatre. This hot house amplified their importance in each other’s lives; family dynamics are seldom more complex and long-lived than in the love and rivalry of sisters.

‘You have the children, the fame by rights belongs to me,’

Virginia Woolf famously wrote to her elder sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, expressing an age-old sense of natural sisterly justice. But this fragile balancing act was overthrown in the du Maurier family. For as it transpired, Daphne, the middle sister, not only had the fame but also the children, the beauty, the money, the dashing war-hero husband; she won all life’s prizes, her fame so bright that it eclipsed, in the eyes of the world, her two sisters and their creative efforts as writer and painter. However, Daphne did not value these prizes. Nothing mattered as much to her as the flight of her extraordinary imagination that animated some of the most haunting stories of the twentieth century.

Her elder sister Angela, more extrovert and expressive, had the emotional energy for children and wrote of her longing to have been a mother. Certainly fame too promised to bring her more pleasure than it ever did to Daphne, who recoiled from publicity and the importuning of fans. Angela, eclipsed as she was, nevertheless came so close to claiming a share of the limelight; when she turned to singing she did not even get to first base as an opera singer, although her love of opera was to last a lifetime and she tried yet failed to join her parents’ profession and become an actor. Insecure and easily discouraged, she quickly abandoned her youthful dreams of a life of performance as enjoyed by her parents. Instead, her emotional nature found an outlet in fiction, a highly regarded aspect of the family business thanks to the success of their grandfather the artist George du Maurier, whose late career as a novelist brought him transatlantic fame.

Soon after the publication in 1928 of Radclyffe Hall’s notorious novel, The Well of Loneliness, a plea for understanding ‘sexual inversion’ in women, Angela began writing her own first novel, The Little Less. Given the damning prejudices of the time, together with her father’s powerful influence and horror of homosexuality, Angela showed surprising courage – even revolutionary zeal – in exploring the bold theme of a woman’s love for another. Like The Well of Loneliness, Angela’s novel was not a great literary work, but it was a brave one and would have brought her a great deal of notice and some riches. Publication and attention would have established her as a novelist to watch and encouraged her to continue, and grow. Instead, she was met by rejection from publishers scared of another scandal. Her tentative flame of independence was snuffed out and she was left demoralised, perhaps even ashamed, for she had thrown light on a taboo subject and been silenced. She put the manuscript away, returned to the distraction of a busy social life and did not write again for almost a decade.

Meanwhile, Daphne had been writing a few startling short stories since she was a girl and then, sometime later in 1929, had begun her first novel. The Loving Spirit, a rather more conventional adventure story, was spiced with what was to become the characteristic du Maurier sense of menace. This too was not a particularly good book but it was a much safer subject and easily found a publisher in 1931. Daphne was launched as a writer on a spectacular career that powered her through four books in five years to the darkly atmospheric Jamaica Inn and then, two years later in 1938, her creative prodigy Rebecca stormed to bestseller status. The momentum was now entirely with her. Daphne’s writing career, financial security and reputation were all made by the phenomenal success of Rebecca, and the haunting Hitchcock film that followed. The eclipse of her sisters was complete.

Jeanne, seven years younger than Angela, had also made a bold move that went against the powerful family ethos. She had tried her hand at music and was a fine pianist all her life, but her real love was painting. Hers was a family brought up to decry anything modern in the arts. The French Impressionists, the English Post-Impressionists, whose exhibition in London in 1910 had caused uproar among polite society, all horrified their father Gerald du Maurier. He was vocal in his derision of any art after the mid-nineteenth century and his opinions were held in Mosaic regard by his adoring family. ‘Daddy loathed practically everything that was modern. He hated modern music, modern painting, modern architecture and the modern way of living … Gauguin horrified him I do remember,’ Angela wrote, adding, ‘I’m not at all sure it’s a good thing to be as impressed by one’s parents’ ideas and opinions as I was by Daddy’s.’

Angela was not alone. All the sisters were in awe of their father’s opinion on most things and Angela and Daphne never came to appreciate twentieth-century art. This made it all the more remarkable, but also painful for her, that Jeanne made her career as a painter, not of conventional, narrative, realistic pictures that her family might have appreciated, but of quiet, contemplative, modernist works. Her family did not value her art enough to hang it with pleasure on their walls, although her paintings were considered good enough by the art establishment to be bought by at least one public gallery. Jeanne seemed not to long for children, neither did she court fame, but her painting was the mainspring of her life and her immediate family’s lack of appreciation of her work was a kind of denial too.

The intriguing threads of inheritance, character, family mythology and circumstance combine with early experience to create the pattern of a life. It is in childhood that these elements make their deepest impression. Here can be found possible reasons for Angela’s lack of perseverance that became a lasting regret: ‘I have always been an easily discouraged person … I had not the “guts” to start again writing’.

Inheritance and familial experiences gave Daphne the contrary commitment; imagination and writing were the things most worthwhile in life. It helped that her talent was encouraged by her doting Daddy who saw so much in his favourite tomboy daughter to remind him of his own father. ‘[He] told me how he had always hoped that one day I should write, not poems, necessarily, but novels … “You remind me so of Papa,” he said. “Always have done. Same forehead, same eyes. If only you had known him.”’

In childhood Jeanne found the seeds of her later independence. Her mother’s favourite and perhaps the most honest and down-to-earth of them all, she was the youngest sister who chose a discredited style of painting as her life’s work and managed to live openly until her death with a woman poet as her partner, despite the oft-expressed antipathy of her father towards people like her.

The sense the family had of being glamorous, exceptional and blessed with French blood was reinforced by the private language they shared. This was a highly visual and entertaining creation that bound them together as a tribe and kept out pretenders. Daphne’s fascination with the Brontës and Gondal, their imaginary world, brought the verb ‘to Gondal’ into the sisters’ lexicon, meaning to make-believe or elaborate upon. Nicknames too were a du Maurier habit. Angela became various forms of ‘Puff’, ‘Piff’ and ‘Piffy’; Daphne was ‘Tray’, ‘Track’ or ‘Bing’; and Jeanne was ‘Queenie’ or ‘Bird’.

Exploring Daphne’s character and work in the context of her sisters, means she appears in a quite different light from the one that shines on her as the solitary subject of a life. She was shyly awkward and intransigent, a girl who escaped into her own imaginary world, where she was supreme. Intent on wresting control over her destiny she thereby influenced the lives of others, not least her sisters’.

In introducing her two much less famous sisters, I hope this book draws them from the shadows. I like to think that Angela, who longed for more notice during her lifetime and dreamed of having a film made from at least one of her stories (Daphne had ten – the unforgettable Rebecca, The Birds and Don’t Look Now among them), would have been delighted to be rediscovered, her books read, possibly even inspiring a belated dramatisation. Where Daphne controlled her universe, Angela, at the mercy of her emotions, seemed to be buffeted by hers. Unfocused when young, and wilting under pressure, her youth was marked by humiliations and missed opportunities, while she was intent on the pursuit of love. Later she discovered a remarkable courage to tackle in her novels and her life injustice in matters of the heart, and to live as unconventionally as she pleased. As she aged, however, the constraining bonds of her Edwardian upbringing tightened around her once more.

A little light shed on Jeanne might also lead to a wider audience for her art, with paintings taken out of storage in small galleries and hung on the walls, for new generations to appreciate. The largest public collection is at the Royal West of England Academy in Bristol, where the quiet atmospheric beauty of her works rewards the eye with a spare, unsentimental vision. She was perhaps the most solid and least flighty of them all. Jeanne was always the honest, boy-like sister and did not apparently struggle with questions of identity or her role in life. When she decided what she wanted to do, all her energy was committed to it, unlikely to be deflected by emotion or propriety.

Much has been written on every aspect of Daphne du Maurier’s work and life. Margaret Forster’s impressive biography published nearly twenty years ago remains the authority on her life, but there are other essential contributions from Judith Cook’s Daphne: A Portrait of Daphne du Maurier and Oriel Malet’s Letters from Menabilly. Her daughter Flavia Leng’s poignant memoir adds another layer of understanding. Daphne’s writing attracted penetrating analysis in Avril Horner and Sue Zlosnik’s Daphne du Maurier: Writing, Identity and the Gothic Imagination, and in Nina Auerbach’s personal take on the themes of Daphne’s fiction in Daphne du Maurier, Haunted Heiress. The rewarding mix of The Daphne du Maurier Companion, edited by Helen Taylor, and Ella Westland’s Reading Daphne, add their own layers of meaning. There is also a highly successful yearly literary festival at Fowey, established to honour Daphne’s close connection and imaginative contribution to that part of south-east Cornwall.

In this book I do not set out to write a full biography of each sister; nor have I the space to analyse their individual works in any depth, although I have discussed them when they offer extra biographical or psychological insights to the story. I have considered the du Maurier sisters side by side, as they lived in life. This adds a new perspective to the characters of each, as they evolve through the tensions and connections of ideas and feelings that flow within any close relationship. Most marked is how much the opinions and experiences of one sister find their way into the work of another. In their fiction particularly, Angela and Daphne each used aspects of their sisters’ lives to animate her own work. But all the du Maurier sisters drew on their unique childhood, a past that was always present, bringing light and dark to their lives and work.

1

The Curtain Rises

Coats off, the music stops, the lights lower, there is a hush. Then up goes the curtain; the play has begun. That is why I’m going to begin this story ‘Once upon a time …’

ANGELA DU MAURIER, First Nights

TO BE BORN a du Maurier was to be born with a silver tongue and to become part of a family of storytellers. To be born the last of the du Mauriers, as the three sisters would be, was to be born in a theatre with the sound of applause, the smell of greasepaint, and the heart attuned to drama, tension and a quickening of the pulse. The du Mauriers were in thrall to myths of their ancestors. Even the romantic name that meant so much to them was an embellishment on something more mundane. As soon as they were old enough to understand, Angela, Daphne and Jeanne du Maurier realised they were special and had inherited a precious thread of creative genius that connected them to their celebrated forebears.

Although Daphne did marry, all three sisters evaded the conventional roles of wife and mother and rose instead to the challenge of living up to their name, a name they never relinquished. Two sisters expressed themselves through writing and the third through paint. The du Maurier character was volatile and charming, inflated with fantasy and pretence; characteristically they hung their lives on a dream and found little solace in real life once the romance had gone.

These three girls inherited a name famous on both sides of the Atlantic: their grandfather George du Maurier was a celebrated illustrator, Punch cartoonist and bestselling novelist. His most famous creation was Trilby and this sensational novel enhanced his fame and made him rich: it gave the world the ‘trilby’ hat and made his anti-hero, the mesmerist Svengali, part of the English language as a byword for a sinister, controlling presence. It was his first novel, Peter Ibbetson, however, that impressed his granddaughters most, insinuating into their own lives and imagination its haunting theme that by ‘dreaming true’ one could realise the thing one most desired. The sisters attempted in their different ways to practise this art in life and incorporate the idea in aspects of their work.

George’s grandfather, Robert, had expressed his love for fantasy by inventing aristocratic connections for his descendants and adding ‘du Maurier’ to the humble family name of Busson. His own mother Ellen, great-grandmother to the sisters, was filled also with the sense she was not a duckling but a swan. As the daughter of the sharp-witted adventuress Mary Anne Clarke, she was brought up with the tantalising thought that her father might not be the undistinguished Mr Clarke, but the Duke of York, the fat spoiled son of George III. Such stories, lovingly polished through generations, contributed to the family’s sense of pride and place. Only Ellen’s great-granddaughter Daphne, with her cold detached eye, was not seduced. She recognised the destructive power of this pretension: ‘She will wander through life believing she has royal blood in her veins, and it will poison her existence. The germ will linger until the third or fourth generation. Pride is the besetting sin of mankind!’

Yet the du Maurier story ensnared her too.

The family myths centred on these three tellers of tall tales: Mary Anne, Robert and the sisters’ grandfather George du Maurier. If imagination and creativity ran like a silver thread through the du Mauriers, so did emotional volatility and lurking depression. In some this darkened into madness, with George’s uncle confined to an asylum and his father so subject to bi-polar delusions (he believed he could build a machine to take his family to the moon) that he lived a life of impossible ambition and frustrated dreams. Some of these soaring flights of fancy would find alternative modes of expression in subsequent generations.

George’s elder son, Guy, like George himself with Trilby, was overtaken in 1909 by an extraordinary flaring fame with An Englishman’s Home, a patriotic play he casually wrote before going to serve as a soldier in Africa. This was five years before the start of the Great War and he satirised his country’s unpreparedness. Sudden international celebrity was followed too soon by Guy’s heroic death in the world war he had foretold. George’s youngest child, Gerald, became an actor whose naturalistic lightness of touch changed the face of acting, where life and art seemed to combine in an effortless brilliance. Gerald made memorable the character of Raffles, the gentleman thief, and was the first actor to play J. M. Barrie’s Mr Darling and Captain Hook in Peter Pan. His portrayal of this unpredictable cavalier pirate set the template for that character’s appearance and behaviour in subsequent productions. This was the father of the du Maurier sisters, Angela, Daphne and Jeanne.

As with all sisters, the du Mauriers’ relationship with each other was an indissoluble link to their childhood: for them that meant above all a link with their father and with Peter Pan. The play’s creator, J. M. Barrie – Uncle Jim to the girls – was a prolific and successful Scottish author and playwright who, nearly a generation older than their father, had been influential in Gerald’s early career and become a friend. Ever since they could first walk, the girls were taken on the annual pilgrimage to see the play performed at their father’s theatre, Wyndham’s. There, as the pampered children of the proprietor, they sat dressed in Edwardian satin and lace in their special box, saluted by the theatre staff and stars. They were celebrity children.

Throughout their childhood the sisters would re-enact the play in their nursery, the words and ideas becoming engraved deep into their psyches. Daphne was always Peter; Angela was more than happy to play Wendy, while Jeanne filled in with whatever part Daphne assigned her. Peter Pan excited their imaginations and intruded on every aspect of their lives. Their father was closely identified with the double personae of Mr Darling and Captain Hook, and Peter himself, brought to life the same year Angela was born, remained the seductive ageless boy. While the du Maurier sisters reluctantly accepted that they had to grow up, Peter Pan lived on in an unchanging loop of militant childishness, mockingly reminding them of what they had lost. The excitement and wonder of the theatre, however, was something they never lost. It informed their lives, finding expression in their work, in the dramatic character of their houses and their attraction to those with a touch of stardust in their blood.

Angela claimed Peter Pan as the biggest influence in her childhood: she saw it first performed when she was two and then finally played the role of Wendy in the theatre when she was nineteen. Her steadfast belief in fairies and prolonged childhood was encouraged by the play’s compelling messages. But the influence on Daphne was profound, for her own imagination and longings so nearly matched the ethos of the story: the thrill of fantasy worlds without parents; the recoil from growing into adulthood and the fear of loss of the imaginative power of the child. The tragic spirit of the Eternal Boy plucked at the du Mauriers, just as he did the Darling children who left him to enter the real world stripped of magic. The place between waking and dreaming would be very real to Daphne all her life and her phenomenally fertile imagination propelled her into her own Neverland, whose inhabitants were completely under her control.

Neverland was never far away. Daphne still referred to Peter Pan as a metaphor when she was old, considering her children’s empty beds and imagining the Darling children having flown to adventures that she could not share. Her powerful identification with this world of make-believe fuelled her spectacular fame and riches and an intense life of the mind, but held her back in her growth to full maturity as a woman. Her sisters, excited by the same theatricality in their childhoods, responded very differently. Angela, never quite taking flight, was shadowed by her sense of earthbound failure, yet she had the courage to grow up and risk her heart in surprising ways. Jeanne largely cast it off to go her independent way and turned to the down-to-earth pleasures of gardening, and the sensuous realities of paint. These evocative childhood experiences brought the sisters not only the comfort of familiarity – ‘routes’ in du Maurier code – but nostalgia too for the past they had so variously shared. Just a word could transport them back to the thrill of the darkened theatre of their youth, full of anticipation of the big adventure about to begin. ‘On these magic shores [of Neverland] children at play are for ever beaching their coracles. We too have been there; we can still hear the sound of the surf, though we shall land no more.’

These du Maurier girls were born as Edwardians in the brilliant shaft of light between the death in 1901 of the old Queen Victoria and the beginning of the First World War. It was a time when new ways of being seemed possible: pent-up feelings erupted into exuberant hope in the dawn of the twentieth century. Under a new and jovial king, the longing for pleasure and freedom replaced Victorian propriety and constraint, and this energy infected the nation. Such optimism extended to a young theatrical couple who married in 1903. Gerald du Maurier, as an actor and then theatrical manager, was already on a trajectory that would bring him fame, riches and a knighthood. His wife was the young actress Muriel Beaumont, cast with him in a comic play, The Admirable Crichton, a great hit in the West End. She was very young when responsibility and care for him was passed ceremonially to her from his mother (for whom he would remain always her precious pet ‘ewe lamb’) together with a list of his likes and dislikes. Muriel was a pretty actress who eventually gave up her career to be the wife of a great man and the mother of his children. Her two elder children would recall her impatience and irritability when they were young, her lack of humour, and her beauty, always her beauty.

On cue, just over a year after their marriage, on 1 March 1904 a plump baby girl was born in No. 5 Chester Place, a terraced Regency house close to London’s Regent’s Park. While Muriel laboured in childbirth with their first child, Gerald managed to upstage her. Suffering a serious bout of diphtheria, a potentially fatal respiratory disease, for which the cat was blamed, he lay in isolation on the floor above and, it seemed, at death’s door.

When Gerald had recovered and could at last see his firstborn he was delighted to have a daughter. Girls were a rarity in this generation of du Mauriers. His sister Trixie had three boys, Sylvia five, and his brother Guy and wife Gwen were childless. Most importantly, his adored father George du Maurier had longed for at least one granddaughter. ‘That endless tale of boys was a great disappointment. If only he was here to see Angela.’

For Angela is what this jolly baby was called.

In the du Maurier family it was not enough to be a girl, however rare. Aside from ancestor worship, this was a family who adored beauty, demanded beauty, particularly in its women. This aesthetic sensibility was very marked in George whose drawings of gorgeous Victorian wasp-waisted females graced his witty cartoons. Despite his father’s good looks, Gerald’s attractiveness owed more to his charm and animation than the rather ungainly proportions of his face. He may have thought himself lacking in romantic good looks, but he was lightly built and elegantly made and expected grace and beauty in others, especially his womenfolk.

Gerald’s wife Muriel was exceptionally attractive and stylish all her life, but their first daughter, by her own admission, was not: ‘I was a plain little girl, and I got plainer. Luckily, when I was small I was, apparently, amusing, but no one could deny I was plain.’

Muriel was still pursuing her acting career and baby Angela was handed over to ‘Nanny’ when she was eight months old, heralding Angela’s first great love affair in a life in which there would be many. This kind, inventive, affectionate young woman was the central loving presence in Angela’s universe and when she was dismissed, as surplus to requirements eight years later, the little girl’s bewilderment, grief and loneliness seemed to her ‘like a child’s first meeting with Death’.

Angela’s earliest memories, before her sisters joined her in the nursery, were fragments of life. Between the ages of two and three she could remember her canary dying and being replaced, seamlessly, by another. This sleight of hand was enacted a few times more during her childhood. She remembered dancing as her mother played on the piano the hymn, Do No Sinful Action, and being sharply reprimanded for this serious but inexplicable sin. But her very first memory was of wetting her pants in Regent’s Park when dressed in her Sunday best of bright pink overcoat with matching poke bonnet, trimmed with beaver fur. To complete the vision of prosperous Edwardian childhood, white suede boots clothed small feet that were not expected to stamp in puddles or run in wet grass. This memory of her immaculate outward appearance, contrasting with the shameful evidence under her coat, remained with her for life.

When Angela was three the family moved to 24 Cumberland Terrace, a larger house in a grander terrace a few hundred yards away, just as close to Regent’s Park. Muriel was expecting another baby and this time it was hoped she would produce the son and heir. Gerald’s obsession with his father made him long for a boy who might embody some of the lost qualities of artistry, imagination and charm that so distinguished George du Maurier: he wanted continuance of the du Maurier name and his father’s genius somehow reincarnated in a son.

The baby was born late in the afternoon of 13 May 1907. After a week of heat the weather had finally broken and rain pelted down from a thunderous sky, and into the world came not the expected son but another daughter, although this time she was pretty, which was some consolation. Angela did not remember her sister’s arrival but she recalled her mother insisting ‘she was the loveliest tiny baby she has ever seen’.

Gerald was playing that night to packed houses in a light comedy called Brewster’s Millions. The eponymous hero, who had to run through a million-dollar legacy before he could inherit another seven million, mirrored something of Gerald’s own cavalier attitude to money: his characteristic off-hand style and sense of fun endeared him to the audience. He returned from the theatre to find Nanny in charge of this second daughter.

Gerald decided to call her Daphne, after the mesmerising actress Ethel Barrymore, who had much preferred the name Daphne to her own, and had jilted him before he had met Muriel. One wonders if Muriel knew after whom her second daughter was named – perhaps thinking the impetus was the nymph Daphne who ran from Apollo and his erotic intentions (as a last resort transforming herself into a laurel tree), rather than the American beauty from a great acting dynasty who ran from Gerald and his ravenous need for uncritical adoration.

Daphne fitted into a nursery routine long practised by Nanny and Angela. Angela was almost four and for nearly all that time had been the focus of Nanny’s love. She may not have remembered her sister’s birth but recalled she had to relinquish sole command of the nursery and share her beloved with a demanding interloper. Apart from a couple of terms, Angela did not go to school and was not able to establish a new kingdom for herself outside the confines of the nursery. Life continued in its soothing routines but now everything had fundamentally changed.

The highlight of the day was the walk to the park with the enormous coach-built pram, enamelled white to match their front door. There Nanny met other nannies and their charges were allowed some sedate play while the women chatted. The sisters were always impeccably dressed, and dressed alike, something that frustrated them as they grew older and struggled for their own identities. Their days were spent away from their parents, everything done for them by Nanny who never, it seemed to Angela, had a day off. In her eight years’ employment with the family there were only two holidays, but looking back this was such an unjust state of affairs that Angela wondered if she had misremembered it.

The children were brought to their parents at the end of the day, washed, brushed and on their best behaviour. Good manners and above all quietness were instilled into them from an early age; Gerald was extremely sensitive to sound: even the singing of a blackbird could be too plangent for his peace of mind. As he and Muriel slept late and had a rest in the afternoon when they were working, Angela and Daphne, whose nursery was on the floor above their room, learnt to creep around and talk in whispers. When he was available to them, however, he was unusually interested in their young selves, endlessly inventive, funny and full of jokes and games. He was iconoclastic and mocking of others behind their backs and drew his daughters into the joke, though insisting at all times they maintain high standards of politeness and deference to adults, to their faces.

Muriel finally gave up the stage when she was pregnant with her third baby – surely this time a boy. Angela had been praying for years for a baby brother, perhaps giving voice to the whole family’s hopes. She was just seven years old when Gerald and the doctor came into the nursery at lunchtime to tell them that they had a new baby sister. Angela, ever one to enjoy the dramatic in life and art, got down from the table (she had been eating cold beef and beetroot) and walked to an armchair where she knelt and gave thanks. Jeanne was born on 27 March 1911, the day after Gerald’s thirty-eighth birthday. Perhaps by now he was resigned to the lack of a son, for Muriel, at thirty, seemed unwilling, or unable, to add to their family.

Luckily, Jeanne too was a pretty baby who managed to keep her crowd-pleasing charms; according to Angela, between the ages of two and six, Jeanne was the loveliest child she had ever seen. This verdict was not just a big sister’s pride, for the infant won a baby beauty contest. Having given up work during her pregnancy, it was not perhaps surprising that with more energy and time for her children Muriel’s youngest became her favourite. Gerald’s energies too had shifted. His career had been given greater propulsion when in 1910 he became an actor-manager by joining with partner Frank Curzon to manage Wyndham’s Theatre, in London’s West End. Although the current play there, Mr Jarvis, was a flop he was to have many more successes than failures and the family’s income and consequent standard of living rose dramatically.

The girls’ childhoods were lastingly vivid to them, revisited often in memory and in the atmospheric energy of Angela’s and Daphne’s fiction. Their experiences, however, were very different. Angela was romantic and theatrical and easily gulled. Daphne was critical, detached and distrustful, even from young, of some of the stories told by the adults who cared for them. Angela was convinced that Father Christmas was real and, overcome with excitement, had swept the lowest curtsey possible when, aged seven, she came across an actor friend of her father’s in full fig of snowy beard, buckled red tunic and a throaty Yo ho ho. She was twelve when a friend’s insistence that the philanthropic old gent did not exist sent her to her mother in panic, certain she would be reassured: ‘When poor Mummie apologised and said, “I’m sorry darling, I’m afraid there isn’t,” [it] knocked the bottom out of childhood. With that bit of news went a bit of one’s trust.’ It was remarkable that she had maintained her belief almost into adolescence, testament to their isolation from other children, but also to Angela’s resolute romanticism and childlike sense of wonder.

The maintaining of childish innocence, even ignorance, was positively encouraged by their father who loved having his family around him and dreaded his children growing up. Through his profession he conjured the theatrical template for Captain Hook, but in life he was a true Peter Pan, ever youthful, full of tricks; ‘gay, innocent and heartless’

as the boy who was afraid to grow up. Nowhere was this enforced innocence more pernicious in its effects than in the area of sex. Angela was told some fantastical story of where babies come from involving angels descending from the sky bearing fluffy bundles; a common enough deception at the time, but one that the highly emotional Angela would take to heart. When she was enlightened with the real truth in graphic detail by a ‘Miss Know All’, she was disgusted. ‘My father would never do such a thing,’ Angela declared in alarm. But worse than the crude explanation was the realisation that she had been lied to by the people she trusted most.

The twelve-year-old worked out that the reason for these lies was ‘because the truth was so HORRIBLE that they couldn’t bear to tell it to me’. Inevitably, the parents got to hear of the schoolgirl chatter and Angela, somehow singled out as the source of this taboo revelation, and overcome with fear and shame, faced her appalled mother. Muriel ‘harangued [her] like the devil for having learned the truth’,

and histrionically declared she could never trust her daughter again. Angela’s anger and dismay were still alive three and a half decades later when she wrote in her memoir how it was inevitable that she concluded, ‘“all that” [sexual intercourse] was horrible, unnatural, repulsive, disgusting and ugly’.

It came close to blighting her emotional future, she explained; her youth, her whole life even, ‘came near to ruin’,

through this particular piece of evasion and the shame-filled aftermath.

Daphne was never so blindly trusting of those closest to her. Nor was she ever as naïve. When she was six, and Angela nine, she saw through Nanny’s pretence that there were fairies on the lawn who made the fairy-ring of flowers and wrote little notes addressed to both girls by name in tiny fairy writing:

Angela, eyes wide open in wonder, smiled delightedly. I stared at the circle. I must pretend to be pleased too, but the trouble was I did not believe in them … ‘They [the adults] wrote it themselves,’ I said after we got back.

‘They wouldn’t! Of course it was real.’ Angela was indignant.

I shook my head. ‘It’s the sort of thing grown-ups do.’

All three du Maurier sisters were taken to the theatre from babyhood, to proper adult plays in which their father starred. They were treated by the cast and the theatre staff as special mascots: the glamour of the performance and the excitement when the lights went down deeply impressed these little girls and the memory stayed with them for life. Only once did Angela go as a small child to a pantomime, but she was so horrified by the harlequinade at the end – ‘something about a sausage shocked me at four’

– that she would not subject herself to another until she was nearly grown up.

The girls regularly saw their father and mother dress up, put on make-up and become other people. It was the most natural thing to do. They visited Gerald in his dressing room after performances to find him high with adrenaline, charismatic, laughing and talking animatedly to the hordes of friends and acquaintances that always surrounded him, wiping the greasepaint off his face to return in stages to a heightened version of himself. It was thrilling and confusing and somehow conspiratorial, this almost magical transformation. Most of the family friends were also actors and actresses and they too practised this occult art. They seemed to live more intensely, their lives shiny with colour and light but speeded up, and soon over. The excitement fuelled childish imaginations and the glamour and theatricality of their existence blurred the boundaries between truth and fantasy. But if childhood certainties were proved no longer safe, what other truths would disappear as the lights went up?

For Daphne, the fantasy world she inhabited was created by her own imagination, a refuge from a world in which she felt alien and adrift. She remembered that at only five years old, after being bullied in nearby Park Square Gardens by a seven-year-old called John Poynton, she came to the cheerless realisation that everyone was ultimately alone. From very young, feelings of powerlessness and being misunderstood made her long to be a boy and therefore stronger, braver, and more important – not this outer, more vulnerable, female self. She discovered that she, like her parents, could dress up and pretend to be someone else, but for her it was a private thing, a protection from a real world in which she was a stranger. Assuming the persona of another made it less painful when surrounded by unknown adults and their expectations. It ‘stopped the feeling of panic when visitors came’.

Although Angela recalled her first eight years as being blissfully happy in the secure love and care of Nanny, ‘all my very happy early childhood can be laid at [her] door’,

this was brought to a traumatic halt when, completely without warning or explanation, Angela saw this precious mother figure leave the house never to return. ‘I can see Nanny now,’ she wrote at nearly fifty, ‘going down the top flight of stairs and carefully shutting the gate behind her, tears pouring down her face, and only then myself being told she was going for ever.’ Eight-year-old Angela’s cheerful spirits were replaced with ‘a horrible sense of loneliness’.

Daphne remembered this unhappy incident too but with much greater detachment: she was puzzled to see Nanny in tears because surely grown-ups don’t cry. Already, at five, she was aware that adults should never lose their dignity and she herself would very rarely cry, even as a child.

Sadly grown-ups did cry. Tragedies befell the du Maurier family during the earliest years of the girls’ childhoods and it shadowed their father’s careless gaiety. First, Uncle Arthur Llewelyn Davies, married to their beautiful and gentle Aunt Sylvia, died after a long battle with a painful and disfiguring cancer of the jaw. He was only forty-four and his death in 1907, the year Daphne was born, left his wife with five young sons to bring up and educate.

The Llewelyn Davies boys had been the inspiration for Peter Pan and J. M. Barrie, this lonely, childless man who shrank from the harsher elements of adult life, now stepped in to help Sylvia financially and practically with the education of her boys. However, the family’s ills were not over and Sylvia herself had not long to live. Not even the needs of her young family could anchor her to life and three years later she slipped away, aged forty-four, the same age as her dear Arthur. She was Gerald’s favourite sister and he and his family were broken-hearted for she was much loved by all who knew her.

Yet this was not the end of their suffering for only three years later their eldest aunt, Trixie, died unexpectedly aged fifty leaving three mostly grown-up children of her own. She was the most energetic and forthright of them all. It seemed unbelievable that her vibrant spirit had been snuffed out so easily. Only their Aunt May, their father Gerald and the hero-uncle Guy remained of George’s five distinctive children. The Great War was further to devastate this diminishing band of du Mauriers.

In 1914, Lieutenant Colonel Guy du Maurier was waved off by his family at Waterloo Station and headed to war. His mother, Big Granny to the three sisters, was overcome with emotion and collapsed in a dead faint on the platform. Angela and Daphne watched transfixed by the sight of their formal grandmother stretched out, her long black dress decorously pulled round her ankles and her white hair escaping from her bonnet. Within months she too had fallen ill, with heart failure, endured an operation urged on her by her children, and never recovered. According to Daphne, she died in the arms of both her sons. Her death undid the family, and Gerald, her spoiled youngest, particularly felt the loss of her devotion. She had been such a central controlling presence. Her children had deferred to her, written every day while away, sought to please her and been offered all-encompassing love in return.

Only nine weeks later, while everyone was still rapt with grief, Uncle Guy, loved by his troops and his family alike and rumoured to be due promotion to brigadier general the following day, was killed as he evacuated his battalion from the front line. He was not quite fifty. Both Angela and Daphne were possessive of his love and attention for, although he was Angela’s godfather, Daphne shared his birthday. Unhappiness overwhelmed the family once more. Angela was mortified that she had not written to him while he was at the front, despite being his godchild. She was put out that Daphne had sent him letters and felt that somehow this made their hero-uncle, her godfather, belong more to her sister than to her.

The most anguished though was Gerald. He had received the telegram while he was in the middle of his evening performance of the play Raffles and had to go the moment the curtain fell to tell Guy’s widow, Gwen, the awful news. Guy had been the epitome of the heroic elder son. Attractive to everyone for his breezy good humour, he had engaged in the manly things that mattered, and given his life for King and Country. He had also created An Englishman’s Home, the play that seemed to grasp the spirit of the age and for an extraordinary moment take by storm the theatre-going world on both sides of the Atlantic. His success as a writer had somehow proved to Gerald that their father’s genius had not died with him but lived on in Guy, until extinguished tragically too soon.

Guy had added his own robust heroism to his father’s creative flame. All Gerald had done so far was pretend to be other people and provide a few hours’ distraction while momentous events happened elsewhere. He was overcome with regret at having taken his big brother for granted, for not writing often enough; he despaired at the apparent futility of his own life. The devoted family who had loved Gerald as their baby, protected and spoilt him, had been lost to him within a period of only five years. ‘Poor darling D[addy],’ Daphne wrote, ‘had none of his family left but Aunt May.’

Gerald and May, whose health had never been good, had been considered the weaklings and now they were all who remained from the close-knit and glamorous du Maurier clan.

The next tragedy, just a few days later, was made no less painful by the knowledge that personal catastrophe had become commonplace: young men with all their promise before them were dying in their thousands in filthy trenches in a foreign land. The sisters’ cousin, George Llewelyn Davies, one of the orphaned boys, had excelled at Eton and just gone up to Trinity College Cambridge when he joined the Army on the outbreak of war. Less than a week after his Uncle Guy’s death, George, a second lieutenant with the Rifle Brigade, was killed at the front, aged just twenty-one. Everywhere were families overborne by grief.

The sisters could not turn to the comforts of religion and the belief that the beloved dead would be reunited at last, for Gerald had no faith and was an emphatic atheist. Although their mother Muriel and her family were conventionally religious, Gerald’s lack of belief set the tone for the du Maurier children: ‘the Church was a World Apart to us’.

Angela, however, remembered the occasional treat of attending a very high Anglican Mass with her Aunt Billy (her mother’s sister Sybil) where, she admitted, the scent of incense and the ritual ringing of little bells appealed to her emotionalism and theatricality. The rituals of the Anglo-Catholic Church would become a solace to last a lifetime, long after the appeal of Peter Pan had faded.

As for most children, however, the full impact of these family tragedies did not strike as hard, for the routines of daily life continued, offering comfort and entertaining distractions. London was milling with soldiers and their songs penetrated the genteel portals of Cumberland Terrace. Angela, Daphne and Jeanne marched and sang, as the troops did, memorable ditties like Who-Who-Who’s Your Lady Friend? Angela had overheard someone tell their nurse that in wartime everyone made eyes at the soldiers. She interpreted this to mean that it was a patriotic duty and so the girls would practise ‘making eyes’. Daphne thought that the soldiers in Regent’s Park, rewarded with an encouraging smirk and sidelong squint, luckily did not notice.

Their father Gerald, however, was not as emotionally resilient as his children. His mercurial character had found easy expression in his early years through acting. His capricious and light-hearted delivery had pioneered a new informal, conversational style, refreshing after the more self-conscious theatricality of the older generation of actors like Henry Irving and Sir Herbert Tree. Easily bored, Gerald needed constant diversion and had already been tiring of his stage work. However, even the greater challenges in becoming an increasingly successful actor-manager, sharing the responsibilities of selecting plays and cast, directing the acting and reaping the not inconsiderable rewards when a show was a hit, did not banish entirely the sense of ennui that sometimes overcame him.

With the approach of middle age and the harsh realities of death all around, Gerald’s facile emotions as readily flipped into existential gloom. This volatile seesaw of elation and depression ran in the family; his father had sought comfort in his wife and children and a wide circle of artistic friends, and Gerald did the same. To evade the abyss he filled his leisure hours with an endless round of social activity, handled with aplomb by Muriel, whose only desire apparently was to make him happy. Family holidays often involved a small party of friends and hangers-on, largely funded by Gerald whose capacity to earn money increased dramatically along with his readiness to spend it.

He was a demanding and devoted father and, given his emotional nature and love of fun and practical jokes, became the shining sun in his young daughters’ universe. He was a regular in their nursery, ready to play games with them, read stories and preside over mock trials when squabbles broke out between his daughters. More than once he brought J. M. Barrie up to the nursery where the du Maurier girls, without any self-consciousness, acted out for him the whole of Peter Pan: Daphne as Peter, Angela as Wendy and Mrs Darling, and when necessary a pirate or two, while Jeanne was Michael and any other part as necessary. Gerald slipped into his old blood-curdling role of Hook. The girls would slither as mermaids on the floor and fly from chair to chair, thrillingly immersed in their own fantasy of Neverland. In fact for years Angela liked to believe that the lights in Regent’s Park were fairy lights, ‘like those in the last scene of Peter Pan’.

All three sisters pretended to be characters other than themselves throughout their childhood. It seemed that everyone they knew did the same. Histrionics were a way of life. It was not just Angela who screamed she was being murdered if the nurse got soap in her eyes when washing her hair. With Gerald, emotions were magnified; from the anchoritic groans of a man in despair he could become the clown in the nursery or a capriciously domineering Hook. Amongst the children, Daphne was already in thrall to her imagination and became the main mover in the sisters’ dramatic reconstructions of history (executions and torture were popular) or action scenes from books of adventure and derring-do.

Daphne insisted on playing the hero, only deigning to be a girl if the character was warlike and heroic, like Joan of Arc. Angela was happy enough for a while to play the female roles, even though they often ended in tears or death. She remembered the lure of The Three Musketeers, with herself as the responsible, elder Athos. Daphne of course was the upstart outsider d’Artagnan, their natural leader, and ‘poor Jeanne becoming Aramis’.

The older girls didn’t rate the amorous, ambitious Aramis so left him to their little sister who would not complain. No one wanted to be Porthos, whose good-natured gullibility made him too dull to be heroic.

Although Angela recalled being blissfully happy up to the age of eight, in Daphne’s memory her childhood lacked even a few years of uncontaminated happiness. From early on she stood out in the family as the beauty but also as the difficult one. Angela was gregarious and outgoing and in her own estimation was a highly nervous child, but never shy. Manners were everything. The correct appearance of things mattered to the family, and shyness was considered by their parents to be extremely bad manners. Angela could converse with the adults and sweep impressive curtseys when required, but Daphne was not sociable and charming in the way that privileged Edwardian children were expected to be. Already brave and individual, in society Daphne was introverted and shy. When introduced to grown-ups, she was more likely to scowl than simper, and escape to the nursery and her own private world as soon as she could.

Being singled out in the family by her father as his favourite was a perilous honour Daphne was ill-equipped to receive. It was perhaps a major reason for the lack of sympathy between herself and her mother, ‘someone who looked at me with a sort of disapproving irritation, a queer unexplained hostility’. Daphne insisted that from the age of two, when memories began, she had never once been held by her mother or sat on her lap and that this sense of thwarted longing and alienation turned her inwards. ‘I became tongue-tied with shyness, and absolutely shut in myself, a dreamer of dreams.’

It changed the way she viewed the world. She grew watchful and wary, aware always of an uneasy exile. ‘You could never be quite sure of any of them, even relations.’

She recognised Gerald behind his many dramatic personae, but she was disconcerted by Muriel, fearful that her role as mother was just a façade and that she was really the Snow Queen in disguise. If those closest to you appear unpredictable and powerful, as beings possessed of knives, where as a child can you feel safe? This sense of domestic menace fuelled her extraordinarily fertile imagination, expressed all her life in macabre stories and dreams. Where Angela was wide-eyed and believed anything, Daphne took nothing on trust. Extreme wariness and diffidence followed her into adult life, perhaps magnified by her sensitive apprehension as a child that beneath her mother’s lovely exterior existed something deadly to her emerging self. Even in middle age, when she was no longer afraid of a mother who had grown frail and grateful, Daphne’s anxieties found outlet in cinematic nightmares about her, ‘in which my anger against her is so fearful that I nearly kill her!’

There was a cool steely quality behind Muriel’s delicate beauty and this contrast was confusing. She seemed so compliant with Gerald’s extravagances, so ready to act the perfect wife and mother, but even Angela, her responsible eldest and ever eager to please, did not elicit much sympathy from an impatient Muriel who took it upon herself to teach her eldest to read when small and reduced her to tears every time. Despite the apparent self-sacrifice of herself and her career, Muriel was considered by some of her daughters’ friends to be charming, but selfish. Like many of her generation born towards the end of Queen Victoria’s reign she was a snob and very keen that her daughters mixed in the right circles. The girls understood the code of the du Mauriers, as Angela recalled:

blatantly the upper classes and lower classes were alluded to, but the middle class, to which lots of us belonged and we belong, was never mentioned by us! We probably kidded ourselves that we were of the first category, and I squirm when I remember how my darling mother would talk with a sniff about ‘that class’ when speaking of some servant or other.

The highlight of the year for the young du Maurier sisters was the summer retreat to the country. Every May they were dispatched to a rented house with maids and a nurse and there they stayed until August, often without their parents who remained for some of the time in London, acting or dealing with the business of the theatre. Although their behaviour was still constrained by adults’ demands, their country surroundings offered a whole range of new experiences and freedoms denied them in town, where routines and lack of space stifled the spirit of childish adventure and freedom. One significant freedom was to be able to make a noise, to walk and talk without constraint, instead of creeping in silence around their London house in the mornings while their parents slept. Everything became slightly looser. The servants seemed more cheerful, the sisters squabbled less and Mummy did not wear a hat at lunch.

In the summer of 1913, when Angela was nine, Daphne six and Jeanne still only a toddler, the girls arrived at Slyfield Manor in Great Bookham in Surrey. Rented by their parents for the summer, this house impressed the elder sisters with its ancient mystery and the beauty of its surroundings. It was dark and creaky inside, a manor dating back to the Domesday Book, but the current building was largely Elizabethan: the great Queen was meant to have stayed a night here. Perhaps they learnt too of stories of the ghostly blue donkey that leapt the high gates at the bottom of the stairs (installed in an earlier age to keep fierce guard dogs at bay) to disappear into the gloom. Daphne was scared of walking these dark-panelled stairs alone, but the atmosphere of the place and the conjured presence of Elizabeth I stirred her imagination: ‘Where had they all gone, the people who lived at Slyfield once? And where was I then? Who was I now?’

To Angela it was much less complicated. Slyfield was ‘the loveliest house I have ever lived in’.

It was there that this city girl discovered the beauty of bluebells and the intoxicating smell of lilac from a bush beneath her bedroom window. Her happiness that summer was made complete by her infatuation with a farmhand called Arthur who sat her on his great horse. For the first time Daphne felt she ‘had come off second-best’, for Angela ‘smiled down at me, proud as a queen’.

Daphne preferred the farm animals, the great shire horses and the luscious countryside with the River Mole flowing through the manor’s grounds. But mostly the country meant the precious freedom to go off on one’s own, on some adventure, only to return to the adults’ dominion with reluctance and impatience at their intrusion into her world.

Already very unalike in character, both girls seemed to inhabit parallel universes, Angela’s emotional, connected to others and Daphne’s bounded only by her imagination and peopled with her own creations. With a macabre detachment she could dispassionately watch the gardener at Slyfield nail a live adder to a tree, declaring it would take all day to die, and return at intervals to watch it writhing in its desperate attempts to break free. Aunt Billy had given Daphne two doves in a cage and she found it tiresome to have to feed and care for them when she would rather be out doing interesting things. She was struck how Angela loved administering to her pair of canaries and sang while she cleared out their droppings and sprinkled fresh sand on the base of their cage. Daphne’s solution was to set her doves free and accept without complaint the scolding that would be forthcoming, for this was the price of her freedom from care. Jeanne, so much younger, amenably slipped into whatever game or role her elder sisters required. She was pretty and jolly and loved by her mother and nurse, and her life had not yet deepened into its later complexities.

While the children spent the summer at Slyfield, Gerald enjoyed one of his great theatrical successes up in town. He had produced Diplomacy, a melodrama by the nineteenth-century French dramatist Victorien Sardou who was known for the complex constructions of his plots and the shallowness of his characterisation. This play sprang the young actress Gladys Cooper to fame, playing Dora the beautiful spy at the centre of the action. All her life, Gladys was to remain a close friend of the whole family, loved and admired by the du Maurier daughters as much as by Gerald. Angela and Daphne were both taken to see the play in which their father, as producer, had given himself a minor role that he played with characteristic nonchalance. Angela never forgot the dramatic impact at the end of Act Two as the exquisite Dora banged the door hysterically crying, ‘Julian, Julian, Julian!’ When Sardou was asked what tips he would give an aspiring playwright he famously advised: ‘Torture the women!’ It certainly made the play memorable for an impressionable girl of eight and in their nursery productions, Angela would reprise with gusto Dora’s tortured door-banging and weeping. This dramatic scene and the part of Wendy from Peter Pan were her two favourite acting roles, repeated many times with her sisters.

Angela also never forgot her first meeting with Gladys, not just for her luminous beauty at barely twenty-two, but for one of her father’s characteristic roles as the unpredictable joker. On a summer Sunday morning in 1911, when Angela was seven, she and Gerald drew up in the family car at Rickmansworth station to meet the London train. Angela was sent off alone to pick up ‘the prettiest lady’ she could find amongst the throng on the platform. Luckily, Gladys stood out with her fine fair hair and dazzling blue eyes and this small child in her sun bonnet emerged from the crowd and solemnly took the prettiest lady by the hand and without a word led her back to the car where Gerald waited, highly amused. ‘How like my father, Gerald du Maurier!’ recalled Angela decades later, with a mixture of exasperation and affectionate pride.

The year after this great success, Britain was at war. The assassination on 28 June 1914 of the Archduke of Austria in a little known part of the Balkans was the start of what became known as the Great War. Initially, however, there was no great concern at home as eager boys were waved off as part of an expeditionary force; most people thought they would all be home by Christmas. And although everything had changed, in some respects life for the du Maurier children went on in much the same routine. They still spent the summer months in the country, each year gaining greater freedoms. In 1915 they were in Chorley Wood in Surrey and Angela, by now eleven years old, had lessons every day with a family across the common. Daphne was left on her own with their first family dog, Jock, a much-loved bottlebrush of a West Highland Terrier that became her loyal companion on solitary adventures in the gardens and countryside beyond. Jeanne was growing up and at four had become more use to Daphne in her dramatic recreations of adventure stories. This year it was Treasure Island that captivated her: Angela was roped in to playing the supporting parts, and Jeanne filled in as Blind Pew to Daphne’s Jim Hawkins or Long John Silver.

Harrison Ainsworth, a prolific and highly successful historical nineteenth-century novelist, became for a while Angela and Daphne’s favourite author, his stories providing Daphne with plenty of dramatic incident to re-enact with her sisters. The Tower of London provided ample opportunity for torture and death. Angela was happy enough to play Bloody Mary (for whom she admitted some affection) but was proving less tractable to joining in with Daphne’s imaginative games, keener on pursuing her own more grown-up interests. Jeanne, however, was happy to be Daphne’s sidekick and was beheaded many times by her elder sister without complaint. ‘Jeanne, strutting past, certainly made a moving figure, her curls pinned on the top of her head, while I, the axeman, waited …’

Unsurprisingly, Daphne could not recall in these childhood games ever being felled herself by the executioner’s axe, although she would submit occasionally to the torturer’s rack or to energetic writhing in simulating a victim of a rat attack. Catholics and Huguenots provided another thrilling enactment with all kinds of grisly tortures and deaths, but on her terms.

More memorable and exciting even than Slyfield Manor was the family’s visit in 1917 to Milton, a stately colonnaded country mansion near Peterborough, owned by a friend of their mother’s, Lady Fitzwilliam. Daphne recalled with some puzzlement that her usual shyness and diffidence as a child, when confronted with new people and experiences, was here swept aside as she stood in the grandeur of the great hall. Instead she was overwhelmed by an instantaneous feeling of happiness, recognition, even love. This sense of familiarity and affection for the house never left her and much later became conflated with her mysterious Cornish mansion, Menabilly, to create her most famous fictional house, Rebecca’s Manderley.

The girls were only at Milton for ten days, Angela and Daphne sharing one spacious bedroom and their mother and Jeanne another. The sisters entertained and played cards with the convalescing soldiers who were nursed by the Red Cross in the centre of the great house, but there was so much laughter and good humour among the men that the terrors of war did not impinge on the young girls’ thoughts at all. There was too much fun to be had, hiding and seeking in the unused wing, visiting the pack of Fitzwilliam hounds, rabbiting with the soldiers, hanging over the huge jigsaw puzzle that Lady Fitzwilliam worked on most of the time. She nicknamed the du Maurier girls Wendy, Peter and Jim, much to their delight, particularly Daphne’s for she was awarded Peter, that most promising of boy personas.

Despite the war, plays continued to be performed in the West End and Gerald’s successes added to his reputation and his growing fortune. He was becoming more interested in producing than acting but nevertheless, in The Ware Case by George Bancroft, his triumphant production in 1915, took the lead in what his daughter Angela considered one of the finest parts of his career. He played a financier who murdered his brother-in-law, found dead in his garden pond. After a tense trial he was declared not guilty. The trial scene itself was a dramatic novelty for the time and all the more nerve-racking for that. Daphne was gripped by it and recognised Gerald’s acting skills in making the audience believe in Hubert Ware’s innocence, despite so much evidence to the contrary. Angela found it impossible to forget the final scene and the look on her father’s face ‘of hopeless hatred and bitterness’ as he cried: ‘You bloody fools, I did it!’ before taking poison and dramatically collapsing to the stage. She insisted, perhaps a bit defensively, that there was nothing hammy in this at all.

Daphne herself appeared in a charity production at Wyndham’s of a musical version of a play by J. M. Barrie, The Origin of Harlequin, performed in August 1917. The star of the show was a boy, the Honourable Stephen Tennant, at eleven only one year older than Daphne herself, who was struck by how grown up he looked and how well he danced. Stephen was a pretty, clever child who was to grow into an exquisite and talented young man whose life and body became his greatest work of art. The dancing boy had also noticed the young Daphne, but then it was hard to miss her as she was dressed as a Red Indian. Reminded of this fact fifty-five years later, Daphne recalled that the costume was probably a birthday present and she had refused to appear in the show, ‘unless I could be disguised, self-protection I suppose’.

It was inevitable that highly imaginative children, living with this everyday theatricality, would wonder what life was really about. Murderers and fairies crowded the stage, but did the dream end when one awoke? When the lights went up and the crowds left the foyer streaming into the bright night, what was real of whatever remained? Young men were dying in a bloody war just a few hundred miles away; their young cousin, their uncle, were already dead in the slaughter. Confusingly, at home the show went on, with actors pretending to die and children executing each other with imaginary axes, and Daphne dancing on stage as a fully-feathered Indian brave.

Two years earlier Gerald had viewed a Georgian mansion for sale in the leafy village of Hampstead. Cannon Hall had once been a courthouse and it stood in proud command of its demesne of large gardens and various outhouses including a lock-up – much to the sisters’ pleasure – a real jail at last. Gerald was immediately struck by the Hall’s theatrical staircase and decided then and there that he would have it. To return in some style to the area of London where his father had lived and he had grown up seemed to add a nice symmetry to his restless life and would perhaps help to recapture some of the happiness and contentment that had gone. As Gerald attempted to reconnect with his past, he was unconsciously setting a new scene for his daughters’ future.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/jane-dunn/daphne-du-maurier-and-her-sisters/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Jane Dunn

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 493.36 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The Du Mauriers – three beautiful, successful and rebellious sisters, whose lives were bound in a family drama that inspired Angela and Daphne’s best novels. Much has been written about Daphne but here the hidden lives of the sisters are revealed in a riveting group biography.The middle sister in a celebrated artistic dynasty, Daphne du Maurier is one of the master storytellers of our time, author of ‘Rebecca’, ‘Jamaica Inn’ and ‘My Cousin Rachel’. Her success and fame were enhanced by films of her novels and horrifying short stories, ‘Don’t Look Now’ and the unforgettable ‘The Birds’ among them. But this fame overshadowed her sisters Angela and Jeanne, a writer and an artist of talent, living quiet lives even more unconventional than Daphne’s own.In this group biography they are considered side by side, as they were in life, three sisters brought up in the hothouse of a theatrical family with a peculiar and powerful father. This family dynamic reveals the hidden lives of Piffy, Bird & Bing, full of social non-conformity, creative energy and compulsive make-believe, their lives as psychologically complex as a Daphne du Maurier plotline.