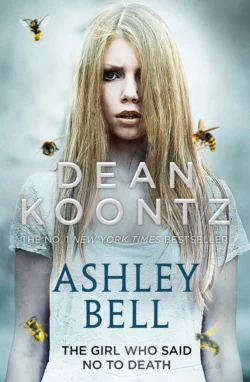

Ashley Bell

Dean Koontz

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Эзотерика, оккультизм

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.17 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From #1 New York Times bestselling author Dean Koontz comes the must-read thriller of the year, perfect for readers of dark psychological suspense and modern classics of mystery and adventure.Bibi Blair is a fierce, funny, dauntless young woman – whose doctor says she has one year to live.She replies, ‘We’ll see.’Her sudden recovery is a medical miracle.An enigmatic woman convinces Bibi that she escaped death so that she can save someone else. Someone named Ashley Bell.But who is Ashley Bell? And what exactly does she need saving from?Bibi’s obsession with finding Ashley sends her on the run from threats both mystical and worldly, including a rich and charismatic cult leader with terrifying ambitions.