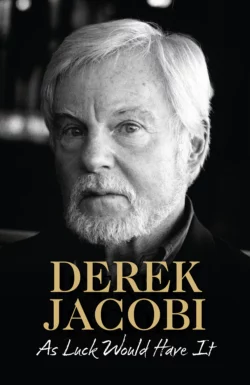

As Luck Would Have It

Derek Jacobi

Star of stage, screen and television, and one of only two people to be awarded two Knighthoods, Sir Derek Jacobi is one of Britain’s most distinguished actors.‘If you want to be an actor, don’t. If you need to be an actor, do.’The world of theatre could not have been further from Derek’s childhood: an only child, born in Leytonstone, London. With his father a department store manager and his mother a secretary, his was very much a working class background. But nonetheless Derek always knew he was going to be an actor, and he remembers clearly the first time he was in costume – draping himself in his mother’s glorious wedding veil as he paraded up and down the Essex Road with his friends.A few short years later, at the age of seven, Derek made his acting debut, playing both lead roles in a local library production of The Prince and the Swineherd. By the age of 18 Derek was playing Hamlet (his most famed role) at the Edinburgh festival. He won a scholarship to Cambridge, where he studied and acted alongside other future acting greats including Ian McKellen. His talent was quickly recognised and in 1963 he was invited to become one of the first members of Laurence Olivier’s National Theatre.Often admired for his willingness to grapple with even the most dislikeable of characters, Derek Jacobi has worked continuously throughout his career, starring in roles ranging from the lead in I, Claudius to Hitler in Inside the Third Reich and Francis Bacon in the controversial Love Is The Devil. But it is his numerous Shakespearean roles that have gained him worldwide recognition.This book is, however, much more than a career record. Funny, warm and honest, Jacobi brings us his insider’s view on the world of acting. From a simple childhood in the East End to the height of fame on stage and screen, Derek recalls his journey in full: from the beginnings of his childhood dreams to the legendary productions, the renowned stars and the intimate off-stage moments.

I dedicate this book to Mum and Dad, and to my teacher, Bobby Brown.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u18abaee5-e301-541f-9902-c8772de698d1)

Title Page (#uc7761227-bc2e-570f-9a40-ed97c02bf8a3)

Dedication (#udc63e0ae-20ce-5ef6-9512-2f174c65727e)

The Seven Ages

Prologue: The Boy with the veil

AGE I INFANT, MEWLING

1 The front room

2 Our war

3 The return of Alfred Jacobi

4 The Christmas Conned ’em

5 Mum

6 Dad

AGE II SHINING MORNING FACE

7 ‘With one little touch of her hand’

8 Confinement

9 East London boy

10 My teachers

11 Intimations of immortality

12 The lads of life

13 The passport prince

14 Cloud-capped towers

AGE III SIGHING LIKE FURNACE

15 First term, first love

16 The Marlowe Society

17 Princes and puppets

18 ‘Honorificabilitudinitatibus’

19 Encounters with a colossus

20 The Brummie Beast

AGE IV SEEKING THE BUBBLE REPUTATION

21 A shameful episode

22 ‘I thought Hamlet looked a bit down at the wedding’

23 Sir

24 Clay feet and other parts

25 Giving away Michael York

26 Leading in the dark

27The Idiot

AGE V AND THEN THE JUSTICE

28 The intangible ‘it’

29 From Kaiser to Emperor

30 ‘Hamlet, played by Derek “I, Claudius” Jacobi’

31 Enter Richard II

32 A marriage proposal

33 Terrible news

34 So we’ll go no more a-roving

AGE VI A WORLD TOO WIDE

35 Ultimate nightmare

36 The RSC

37 Proboscis magnifica

38 The Jacobi Cadets

39 Two broken codes for the price of one

40 Life among the great and good

AGE VII STRANGE EVENTFUL HISTORY

41 My new family

42 The summons

43 Walks on the dark side

44 Russell Crowe’s bum

45 Shakespeare’s end-games

46 Aren’t we all?

Picture Section

Afterword and Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

THE SEVEN AGES (#u19594c11-3cdd-5aa1-bd26-bb473152c50b)

All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players: They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant, Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms. And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel And shining morning face, creeping like snail Unwillingly to school. And then the lover, Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier, Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard, Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel, Seeking the bubble reputation Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice, In fair round belly with good capon lined, With eyes severe and beard of formal cut, Full of wise saws and modern instances; And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon, With spectacles on nose and pouch on side, His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice, Turning again toward childish treble, pipes And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all, That ends this strange eventful history, Is second childishness and mere oblivion, Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Shakespeare, As You Like It, II, vii.

PROLOGUE (#u19594c11-3cdd-5aa1-bd26-bb473152c50b)

The boy with the veil (#u19594c11-3cdd-5aa1-bd26-bb473152c50b)

It shimmers and enchants; it belongs to a secret, magical, forbidden world, and I have always wanted it.

She keeps her glorious white silk wedding veil – part of her wedding trousseau – in her wardrobe, and I sometimes sneak into my parents’ bedroom and gaze at it. And then one day in 1945, when I am six years old and they are both out at work, I creep into their room, open the wardrobe and carefully lift out the veil. I drape the gorgeous white material round my shoulders and over my head, and, swishing it around and puffing myself up like mad, I go out of the house and parade up and down Essex Road.

We East London kids like to play out in the Essex Road and the adjoining streets, and do so in complete safety. The streets of England are our playground. We make dens in the front gardens, and dream and imagine we are other people and characters. From as early as I can remember I have been excited by the idea of dressing up, and this is my first recollection of being in costume.

Perhaps it is to impress Ivy Mills that I have worn Mum’s wedding veil, though my first girlfriend is Winnie Spurgeon. We play hopscotch, and doctors and nurses, with two other girls in the street and we chalk our initials on the pavement. Yet it is Ivy, the prettiest of the three, who has now become my favourite. The boys in my class start to chalk on the pavement, ‘DJ LOVES IM’, and I will do anything to please her.

But on this day I know I’m not just pleasing Ivy. I know in some instinctive way that I am performing, perhaps for the first time in my life, and suddenly all the world – or at least Essex Road – is my stage. And in transforming myself, and entertaining Ivy, I have a sudden insight – a sense of who I am, and who I could be, when I’m not just being myself.

I can become other people in my imagination – but can’t we all? I can be a hero or villain, strong, weak, timid, arrogant, crafty, trusting, passionate, destructive, nurturing ... I can be anything I want to be. After all, I’m a human being, full of everything you can possibly imagine.

Of course Ivy, Winnie and my friends laugh at me and are most impressed. I play up to it for all it’s worth – strutting, waltzing, skipping, galloping around the pavement until my veil is finally shredded to bits on the front garden privets.

Mum was back home when I returned. She was waiting.

‘Well, this is it,’ I thought. ‘She’s going to go completely bananas at me when she finds her precious wedding veil torn into tatters!’

I was starting to cry as I stood there ready for her to tear me to shreds – just as I had torn her wedding veil.

But her reaction wasn’t anger: she hardly told me off at all.

From that moment I continued to fancy myself in the veil. The idea of the veil stuck in my mind as a garment that, whoever wore it, both concealed and revealed the person. Yet the actor in me, the dressing-up part of me, was a mystery which I never could understand, right from the beginning – and that still remains the case today. I can only describe it as a magical process.

Later I would say that the actor must somehow have got in there right from the start, at the moment of conception, but God knows where he came from. Was I simply born an actor, as grandly titled by Edmund Kean – ‘A prince and an actor’ – a part which I was to play later in Jean-Paul Sartre’s play? Even then, in that earlier time as a child, the first part I ever acted was a prince, and this prince was by no means to be the last.

We take it for granted that actors can act; the skill or craft – or the trick – is to make people believe they are seeing somebody real on stage, not an actor acting. Ideally they should leave the theatre talking about the person they’ve seen and the emotions they’ve felt, not saying, ‘Gosh, isn’t he a good actor?’ That suggests that it has been merely a spectator sport, and the actor has been showing off. Audiences or viewers want to believe they have been in the presence of a real person.

But theatre, film and television are trickery; a bit of a performance works, and I glow to myself. I know I’ve managed to carry it off, and it is a moment of pure, private pleasure. As every actor does, I have felt the power and the glory of trickery and mystification.

Yet who would ever have suspected that that little boy who was so excited at putting on his mum’s wedding veil would in time come to play real and fictional people – Hamlet, Lear, Hitler or Alan Turing, and a great host of others? Who could ever have known that he would come to live in the palaces or grand locations of his games and imagination, or re-inhabit in stories the real places, such as Bletchley, or the suburbia-like lower-middle-class Leytonstone, which had an importance in his early life?

It was the fate and destiny established way back in my past, in my childhood or before, that there would be many, many parts, well over the 200 mark through my seven ages, behind which I would hide my true self, conceal myself as behind a veil, yet at the same time be able to reveal some of who and what I was.

AGE I (#u19594c11-3cdd-5aa1-bd26-bb473152c50b)

INFANT, MEWLING (#u19594c11-3cdd-5aa1-bd26-bb473152c50b)

1 (#u19594c11-3cdd-5aa1-bd26-bb473152c50b)

THE FRONT ROOM (#u19594c11-3cdd-5aa1-bd26-bb473152c50b)

It was all a ghastly mistake. The state of the world at that time was such that no one thought of having a family. Hitler was already advancing fast and the world was on the brink of war when I was born in East London on 22 October 1938.

This was in our front room in Leytonstone. My mum – Daisy – struggled in labour for forty long hours to give birth. Forty hours! Has anyone ever taken so long to be born? It must be a record. Mum was completely worn out, and when at last I’d been delivered she sank back and groaned, ‘Never again!’

‘Is this what it’s all been about?’ said our doctor, as he held me up with just his right hand to show Mum and Dad. Mum and I were then placed in an improvised oxygen tent to recover. She had no more children.

The labour may have been endlessly protracted and I was probably the most appallingly mewling, puking infant, but from that moment on I was the sole object of my parents’ love and attention. They lived for me, exclusively and without reservation. Each Christmas Day, for instance, I would wake, rub my eyes and gaze in utter wonder at my presents at the end of the bed: not one but two pillowcases stuffed full of presents of every kind – games, toy trains, Meccano, jigsaws – all just for me!

There would never be anyone else in the house besides the three of us: my parents and me. It encouraged me to have the highest ideals and aspirations, and it may well be that the romanticism stemmed from this extraordinary good fortune of being favoured as an only child, with devoted and loving parents, while they, too, grew steadfastly more romantic about me. They always believed in the best of me – and wanted the best for me – in spite of anything that might not prove them right.

So from the start I had no rival; at times I might have missed the presence of a brother or sister, but actually, I had to remember, not only did I get all the pocket money and all the presents, but I carried all their fears, love and aspirations. As my mum Daisy and my dad Alfred both worked, I thought at first we were favoured with wealth and good fortune, but when I found out we weren’t, it didn’t really matter.

There were few disadvantages in being so well favoured from the start. I might certainly claim that I’ve been ‘dogged’ by good luck, so maybe that’s my misfortune, and the huge obstacles to overcome that most people have to face to make their way in the world – I’ve had very few of these. Heartbreaks yes, but that seriously – as we shall see – is another matter. For I was born a romantic, however much I might want to wrestle with it and deny it. Seventy-five years later I am still as much a romantic as I ever was, and still as unromantic in appearance as ever I was.

Yet I have an abiding sense of never having been taken quite seriously enough – that is, it goes without saying, as I take myself! I’ve always felt there was something about me which doesn’t give off that radiation, that sense of power – either it is my look, or the life journey I’ve been through – which doesn’t have suffering crying out at every twist and turn. It is true that few have taken me as seriously as I’d like to have been taken.

Nor have I championed anything, nor been a martyr to anything – no, and I’ve never been much of a mover or a shaker either, always a follower. If I haven’t suffered enough – mea culpa, I pray I might be forgiven, for isn’t it the dogma of today that to be taken really seriously you have to have suffered? But I haven’t and I can’t help it!

Our terraced house in Essex Road was built in red and brown brick, with an iron gate and tiny paved area in front, bay windows, yellow and red brick features and some fancy stuccoed panels: an average, lower-middle-class property. There were three bedrooms upstairs, Mum and Dad’s, mine, and a spare room. At the back was a modest garden where, as I grew into childhood, I used to run around with friends and knock tennis balls about.

Mum and Dad bought the house before my birth, when George VI was on the throne. They paid £800 for the freehold and it took them twenty-five years to pay off the mortgage. They told me later that when they moved in there were green fields and cows opposite, but these were soon replaced by the inevitable blocks of flats. I don’t remember any green fields or herds of cows, so for me these flats were always there.

The front room was where we went into on Sundays, the special day, the day of rest, although Mum and Dad rarely if ever went to church. It was the room where the best furniture was kept, well dusted and tidy. Where we played and listened to the gramophone records. Where the cocktail cabinet, the central feature of the front room, was stationed, and where Mum and Dad would display the drinks – which would never be drunk most of the year. The expectations of booze, of parents with their gin and tonics or their nightly glasses of wine, not to mention six pints downed at the pub, were never there for any of us – so different from the way it is for many children born today.

The exception was of course at Christmas, when the cherry brandy would be poured, and then imbibed to celebrate the tree lights being switched on. The radiogram cabinet was huge, almost as big as a sideboard. It housed the sole piece of broadcasting equipment – the sacred wireless, with white buttons and dials to twirl and press, and rasps and crackles of static and a muddle and jumble of strange tongues, like Pentecost, to which we all listened dutifully, even religiously. There were just three channels – the Home Service, the Third Programme and the Light Programme – and that was all there was, well before television came along. The notion of constant choice and switching channels just didn’t enter into it.

And so it stayed like that for many years, until I was ten – and to begin with, and for life ever after, the first outlet of my romantic feelings and love was for Mum and Dad, whose whole focus was on me.

Being a happy child and belonging to a small, close-knit family as I did, my memories of childhood mostly centre around the other members of my family who lived locally. There was Grandpa and Grandma, Dad’s parents; Dad’s brother – Uncle Henry; his wife – Auntie Hilda; and their son Raymond. All five of them lived on two floors in Poplars Road, off Baker’s Arms, which was twenty minutes’ walk away in Leyton. Grandpa and Grandma lived upstairs, the others on the ground floor. Grandma Sarah was tiny. She and Grandpa Henry were very sweet, kind and gentle.

In the wider family circle my cousin Michael (son of my mother’s brother Alfred) and Vicky, his sister, lived just down the road, too. Alf Two was very close to Dad. Tall and gangling with dark hair, he was a builder and later built the lean-to or conservatory on the back of our house. He was Mum’s favourite brother, a joker who would have us in fits, but he liked to gamble, and on more than one occasion – as I found out later – got himself into ‘a spot of bovver’. One day after the war he suddenly took off with his wife and two children without telling a soul, and sailed for Australia. Mum was heartbroken. On discovering they had gone she came back from their house furious and upset.

We went round and found the house empty. They really had gone. I think this must have been another ‘spot of bother’ – he’d got himself into a state over money. Even before they left my parents had the feeling that there was something ‘not quite right’, and were suspicious about what was going on in Uncle Alf’s immediate family. Mum wasn’t too keen on the Beardmores, as the family her brother married into were called, and we were all a bit doubtful about them. I grew up wary of the Beardmores: not because they were unfriendly or uncommunicative, but because they were a little odd and eccentric.

There was a brother of my maternal grandmother – a great-uncle who was known as Gaga. He sat around in Hackney and did nothing, but on Dad’s side Grandpa had six brothers, one of whom was a well-known architect called Julius Jacobi who built some of the first skyscrapers in London, although we never knew him or the other Jacobis.

A remarkable feature of Aunt Hilda’s household was the one outside toilet to which I’d head to answer the call of nature. When I was ready I’d call out, ‘I’m ready, Aunt Hilda!’ – the call I made for Auntie to come and wipe my bottom. Grandpa, who was a cobbler and worked for Dolcis all his life, had a shed in the garden to ply his trade and mend our shoes; this was his holy of holies, where he kept all his cobbling tools – I treasure to this day a metal last as a doorstop.

Not only was there no toilet in the house, but also no bathroom. We took our immersions in a tin bath, filled it up with hot water once a week, with a fire blazing in the hearth to keep us warm. But did we feel deprived? Did we feel others had more than we did? Never – it never once crossed our minds.

Mum’s maiden name was Daisy Gertrude Masters. I knew nothing about her paternal background, but her grandmother had the unlikely name of Salomé Lapland, so heaven knows where she came from – most likely from the frozen north – and for all I knew the family could have been gypsies. She had some French relations somewhere, and there were two adored brothers. There were no actors or anyone remotely like artists in her family. She would later claim that my artistic temperament came from her side, for an aunt of hers played the piano!

Mum was pretty, she had a round face, while her hair had turned white when she was in her twenties. She was very conscious of her hair and would go to the hairdressers once a week in Leyton. Dad and I had an old-fashioned barber who lived next door and who would come in once a week to cut our hair. We would lay out newspapers in our front room to collect the cuttings.

I never remember what people look like, but I do remember their voices. The barber had a voice like my uncle Henry, which I learned later had been the result of diphtheria when he was young. It was adenoidal, strained, and he spoke very high, at the top of his throat. His throat had been burned away, or cauterised.

Both my parents were born in Hackney in the same year, 1910. Mum and Dad met first as teenagers, while very much later, in their forties, they both worked at Garnham’s department store in Walthamstow High Street, where Dad managed the crockery and hardware department and Mum was the boss’s secretary and a department supervisor.

‘It was the scout uniform,’ she would say. ‘To woo me your dad had a motorbike with a sidecar. He would come and collect me, and we would go out together.’

They had a modest wooing, with her on the pillion or sidecar. Sometimes my Auntie Hilda and Uncle Henry joined them.

War was declared in September 1939, a month before my first birthday. My memories go back to sitting in a pram when we first heard the air-raid sirens. Mum grabbed hold of me, swaddled and wrapped me up, then rushed me down the steps into the Anderson shelter.

I liked the wail of the sirens and never felt fear. Although we didn’t live in the area of dense, blanket bombing or the fire bombs that set the whole of Docklands on fire, there were explosions enough – flashes, sirens, wailing searchlights crossing the sky and picking out planes and barrage balloons. Somehow I was never affected. I was too young to feel or understand violent death and destruction as a presence.

Dozens of kids from where I lived were sent away in the early months of war with labels round their necks and a single change of clothing, accompanied by teachers, to board with strangers, but with no guarantee they could stay even with brothers and sisters, and not knowing when they would next see their fathers and mothers.

This never happened to me. I never stood on a station platform looking lost and forlorn with a label round my neck.

During the Blitz in 1940–41 I was still in Leytonstone. Dad, being over thirty, wasn’t called up for a while and, like millions of others, dug out and built an Anderson shelter in the back garden. It was purpose-made from sheets of corrugated iron bent into a semi-circular shape. Dad set it over a concrete base embedded two or three feet in the ground. It had no soak-away, but it had bunk beds on either side making four beds in total. Like others, Dad covered it with earth and a little rock garden: planting aubretia, roses, Canterbury bells and geraniums.

I’m not sure if this camouflage decoration put off the Boche from dropping bombs on us. During the raids we were hunched up with sopping feet in the Anderson, which every now and then shook and quaked in the depths from after-shock. I heard later that when I was three one huge bomb fell just hundreds of yards down our road at the junction of Essex Road with Crieg Road in front of the Leyton High School for Boys, gouging out a vast crater.

Grandpa and Grandma were mainly with us during the Blitz. Grandpa stood outside the shelter and stationed himself as if on guard. I can’t say what he thought he would be able to do if a bomb fell on us. I do remember later that if anyone farted in the shelter they were made to stand outside – expelled as a punishment. Perhaps this was what Grandpa kept doing!

Soon I would go away, too; that was inevitable. But to where, and with whom?

2 (#ulink_591c2455-a740-5d90-a105-e2f9faeb5697)

OUR WAR (#ulink_591c2455-a740-5d90-a105-e2f9faeb5697)

Dad was called up into the army and left us in 1941, but as he had bunions so badly (at one time he was in Croft’s Hospital with them, where they cared for him in the maternity ward!) he was never sent abroad to a war zone. As a humble private he served in the Royal Army Service Corps at postings in Scotland, Wales and the South.

When Hitler threatened to invade England Dad was stationed on Clapham Common, pasting up and setting out dummy tanks and guns of painted cardboard on the Common. They used lorries and dug tracks in the ground to make it all look real, so the Luftwaffe flying above would think we were heavily fortified.

Uncle Henry joined the Catering Corps. He was stationed at Reykjavik in Iceland. Later he was posted to a barracks in Buckinghamshire, so eventually – after the Blitz and not necessarily for my safety – Hilda took Raymond and me to stay with her not far from him in Little Brick Hill, a village outside Bletchley, near Cosgrave. We lived upstairs in the village pub. Mum stayed behind in Essex Road working, so she was very lonely and of all of us most exposed to danger. She’d come out to see us at Little Brick Hill whenever she could, and this was always a treat.

But my life with cousin Raymond was quite the opposite.

Raymond and I were billeted together in the pub, sharing a room. My cousin Raymond was six or seven years older than me and I spent a lot of my childhood years with him. Auntie Hilda treated me with kid gloves – she would love the Jesus out of me – while Raymond got the rough end of her tongue. It was he, not me, the golden boy, who always seemed to come in for it.

Not long before we were evacuated there was one hell of a ruction which I will never forget. I was round at Poplars Road and Auntie Hilda asked Raymond to take a jar of precious jam through to the front room and put it in the cabinet where she stored the best pieces. He picked up the jar and pranced up the passageway, puffed up with airs and graces as he went, possibly the more so as I was watching, but as he came through into the front room the lid spun off the jam, and the jam shot out of the jar all over and up the wall. Hilda was so furious that she completely lost her rag and knocked him to kingdom come.

‘Auntie, Auntie, stop it, stop it!’ I screamed, as I stood by terrified.

Now that we were living together in Little Brick Hill, Raymond at last had me in his power and at night under the bedclothes he had the chance to take his revenge. He would scare and terrorise me, tickling me, pummelling me, playing at ‘tortures’ under the sheets.

‘Why can’t he stop trying to frighten me all the time?’ I remember thinking. ‘I am so much younger than him, so why is he tormenting me so much?’

It was pretty obvious to someone a bit older. With hindsight I could quite understand him wanting revenge on me. I was treated as the special one, the one apart from the rest of the family, while Raymond was the ‘bloke’, the laddish one. Later I realised that I was always accepted as the one who didn’t quite fit in, who wasn’t going to take an ordinary route through life.

One day we went apple scrumping together in the orchard of a big house where a grand lady lived – a highly dangerous thing to do, for it was trespassing and illegal. I didn’t feel part of it, but I followed where Raymond led. The school I attended gave a picnic party for the local children, but they wouldn’t allow evacuated kids like Raymond and me to join in. Learning of this, Hilda went ballistic, stormed off to the headmistress, and made such a fuss that in the end, while we were still not included, we were taken back to the pub and had our own picnic. At that tender age I’d never heard language like Hilda’s – it was quite some gab she had the gift of!

All was clear from bombing raids when I returned home to Essex Road in late 1944. Like the thousands of young children sent out of London to avoid the Blitz and the destruction of much of the East End, I was restored to Mum – and Dad when on leave. We were reunited, Hilda and Raymond, too. Grandma and Grandpa were full of joy to see us again. Dad was still away, but hardly very far away: in Clapham.

Victory was in sight. But unknown to us there was a new and even deadlier threat. We came back to what was the most terrifying ordeal of all, the destruction caused by the pilotless planes; first the V1 flying bombs, then the deadly V2 rockets launched on London from mobile trailers.

The flying bombs were like a dark shadow, chugging, rattling and droning across the sky, with their 1,000 pounds of explosive which always seemed to be released at a point just above your head. We would sense that, because the noise would suddenly cut out, and we never knew if they’d glide onwards or fall straight down. During the cold, miserable winter of 1944 we got to know these new weapons: all at once, without any warning, there would just be this eerie silence. They were fired straight into sub-orbital space and came down so fast that if we heard them we had been lucky and had escaped.

One day this happened to us. ‘Face down on the floor everyone!’ shouted the white-coated fishmonger. I was round at Poplars Road. Raymond and I had been sent out to buy fish for Kitty, our cat.

There was a flash and then a huge explosion as the rocket hit the Baker’s Arms bus shelter about 150 yards away. Everyone threw themselves on the floor of the shop. Buildings were blown up or simply collapsed. Debris flew everywhere. Bodies, blood and severed limbs were scattered across the street; ambulances screamed and sirens wailed as fire engines and rescue squads arrived.

Raymond and I had flattened ourselves on the fishmonger’s floor. We’d had a very lucky escape. There was dust and debris everywhere. A woman came up to where we lay flat on our bellies, quivering with terror.

‘Where do you live?’ she asked. ‘Do you live locally?’

This kind woman then took each of us by the hand and brought us back to Auntie’s place in Poplars Road. Here a couple of front windows had been blown out and we found Hilda in a petrified state, sitting on top of the kitchen table. She was perched there as if there was a swirling flood rising around her.

‘You must take shelter under the table,’ she’d been told before the air-raid warning and the rocket struck. Definitely the safest place was to shelter under it.

‘But I can’t, no I can’t!’ she shrieked. ‘There’s a mouse there!’

The Pathé or Movietone newsreels at the cinema where we viewed the horrifying footage of these new terror weapons were miles away from the reality of their destruction. The rockets had a double demoralising effect on a tired and war-weary East London, where destruction had been diabolical. Over 6,000 people died, many in our area, and tens of thousands more were wounded – a huge toll. My evacuation to Bletchley had then proved to be effective because my worst moment of the war was back at home on my return.

Even so, these years, when so many suffered death, destruction and misery, were for me a happy and secure time when only at rare moments was my sense of good fortune disrupted or broken. We were fighting the Germans, but that was all I knew.

I didn’t see much of Dad, so I was hardly aware of him, but in the laundry he sent home to Mum he would include sheets of Bakelite (which he used in his war work in the army to wrap up the imitation planes and soldiers) for me to play with. Aside from the separations, there was such a great spirit with everybody pulling together, and we kids had a great time.

Later when I was a bit older on my return to Leytonstone in late 1944 I remember rushing down the steps in daylight to the shelter, but without Dad. He had gone away and was now a stranger, a shadowy figure who occasionally visited on leave. He played very little part in my life in those early infant years.

Yet even without having my dad there to look after me I was never worried, never scared, and never had any decision to make: I was supremely well cared for by everyone. I never felt lonely and on my own.

I accepted life, I accepted what I was doing, the world around me, and what was happening to me without ever questioning it.

3 (#ulink_6711e433-ac14-5a2f-87d5-e3b62f39161f)

THE RETURN OF ALFRED JACOBI (#ulink_6711e433-ac14-5a2f-87d5-e3b62f39161f)

The war in Europe was over. I had seen virtually nothing of Dad now since 1941 and was excited at the thought of his homecoming.

On Victory in Europe (VE) Day in May 1945 we held a fancy-dress party in Poplars Road. Everyone carried out chairs and tables into the middle of the road and covered the tables in tablecloths of all different shapes and colours.

With basic foodstuffs rationed, we had been fed on spam – plentiful tinned spam – and cheese-and-potato pie was my favourite, which Hilda used to bake. Vegetables were even scarcer than fresh meat, but I was too young to know what they were, so I hardly missed them. Powdered milk and powdered eggs were part of the staple diet, and there was hardly any fruit to eat. Everyone has their first banana story. I had no idea what to do with the first banana I held in my hand, how to peel it and get at the inside, but it was exotic – extraordinary.

Foods which had been scarce were brought out of hiding and piled high: sausages, eggs, cakes, cold chicken, mince pies, cup cakes. Fizzy drinks, too: ginger beer, lemonade, Dandelion and Burdock, and the new import, Coca-Cola.

There were races and stalls, as well as the sumptuous spread, and everyone was merry, danced and sang and had the time of their life. I wore a costume made by Mum out of wartime ration cards and books, all of which she had carefully sewn together. I had a painted sign pinned to the front of my costume – ‘Mother’s Worries’ – and with this I won first prize. They even took a professional photograph of me wearing it as ‘Wartime Ration Boy’.

When Mum took part in the egg and spoon race, she fell over just as she was winning and nearly broke her nose. She was covered in blood and I was screaming. I was terrified by what had happened and suddenly had a terrible premonition and fear that she would die.

I was too young, not yet seven, to take in the speeches on the radio, the thanksgiving service, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, voicing his relief and exultation, and everyone paying their tribute to the King as the Head of our Great Family. All this was going on, yet I missed my chance to listen to the Archbishop of Canterbury who spoke in such a dignified and unselfconscious manner, without an inkling that one day I would be playing his predecessor, Cosmo Lang, who was something of a villain, in The King’s Speech.

When we were back home fireworks lit up the sky, which made me for a moment start up with fear, as not long before flashes and explosions had told a different story.

Uncle Henry could pick up any tune on the piano and play it. Just as victory was declared and we were celebrating at home, he got very drunk. He was the one who had cooked for victory all through the war, and been in Iceland, but now he was very inebriated and started hammering out something on the piano. Turning to us with a big grin he said something in a kind of roaring voice which really upset me, really terrified me.

‘I’m going to set the house on fire tonight!’ he roared.

I instantly burst into tears. I took Uncle Henry’s jovial remark quite literally, instantly remembering the V2 rocket that had hit the Baker’s Arms bus shelter. It seemed the most dangerous thing anyone could say, and even though I knew he was very jolly and drunk I really believed he was about to set our house on fire with a box of matches.

I looked around at everyone and they didn’t seem to mind – but I minded!

The VE Day celebrations in 1945 had been and gone and still no Dad had appeared. But then in 1946 there was a national holiday commemorating Victory in Japan (VJ) Day and suddenly Dad was back, still in uniform. Immense crowds gathered in central London, and the rejoicing was universal. The lights were switched on in Piccadilly Circus and the Coca-Cola sign illuminated. We caught the Tube and joined the great congregation of people. Dad hoisted me up on his shoulders above the crowd to give me ‘a flying angel’.

I loved it. I was with him at last.

This was the first time I reckoned my father as a presence. Would I rush at him, throw my arms around him as Mum did with me? I had a sense of ‘Was I going to like him? Would I take to him?’ It was from both of us, Mum too, this feeling of reticence. Mum and he had to get their lives together after the war. There were to be no more babies – and what about sex? Neither ever spoke about it, and I guess probably never did even with each other. I had no insight into where babies came from: I must have lived in cloud cuckoo land. But I never thought about it. Why should I? We never lived in a sexed-up universe.

I’d love to have talked more to both of them, heard more about their experiences, for what had happened during the war would be with them for the rest of their lives. I never discussed with my mother how it had been for her, never questioned her, which I regret. But everyone, in spite of the extreme deprivation, had helped one another, and we knew what it really meant to be a neighbour.

So many people around us lived life without complaining, not fearing death or injury, and accepting one or the other when it came. Life generally was dedicated to a higher role, and it was rare for those around us to exaggerate their sorrows or miseries, or their survival.

But soon people retreated into themselves again and became self-centred, so that feeling of camaraderie after the war didn’t last long.

4 (#ulink_f3e17ee1-e85a-5ee8-81f3-a59bb5b33448)

THE CHRISTMAS CONNED ’EM (#ulink_f3e17ee1-e85a-5ee8-81f3-a59bb5b33448)

At the end of the same year, Christmas 1945, there were twelve of us at home, and I was now seven years old.

The Poplars Road crowd came to our house every Christmas. After Christmas dinner, for which Mum cooked the turkey – the first I’d ever seen – and after we’d heard the King’s Christmas Day speech on the Home Service – the first since VE Day, 1945 – we settled down to play games. One was called ‘Conned ’em’ (slang for ‘conned them’ and not to be confused with something that sounds identical!). Conned ’em had become a family ritual, and we played for money.

We divided into two teams, and to start someone would find a sixpence. The captain of one team placed the tiny coin of silver under the table, and then each one in turn held their hands under until the captain put the sixpence into one of their hands. Then, watched by the other team, they brought up both clenched fists. The other team took it in turns to guess, plump for a hand, and call out ‘Peace’ if they thought the sixpence was there. It sounds simple, but there were tricks and different calls, which was why it was called ‘Conned ’em’.

On this occasion the betting built up into quite a big pile of money. I disappeared under the table and started to pray I would win everything. They watched as I made my retreat, and as usual Raymond, my cousin, was looking very suspicious. I had a flash of instinct and knew who had the sixpence, so I came out from my hiding place and called out ‘Peace!’ at Raymond.

And that was it. I’d judged correctly: he had the silver sixpence and I’d won the pot. He was furious and stormed out of the room.

It was only much later that I discovered that Raymond was not Uncle Henry and Auntie Hilda’s natural son, but had been adopted. Even at a very early age I had a sense of my own entitlement in the way I was treated by Mum and Dad, and Hilda. I could see that Raymond was sort of humiliated in, or by, my presence. Even so, and despite the fact that he terrorised me somewhat – although not too seriously and certainly not traumatically – we spent a lot of time together.

Looking back I can see how there was a slight conspiracy in the family to protect me as someone different, not quite run-of-the-mill, something that in a way cosseted me as special, as if somehow they knew I was going to break the mould, but were not sure how this would happen.

5 (#ulink_213abb26-b03f-5aab-85e2-0f0c4ae6ad8e)

MUM (#ulink_213abb26-b03f-5aab-85e2-0f0c4ae6ad8e)

Throughout my childhood, Mum would often be sitting at her Jones sewing machine, extending the life of worn sheets and towels by cutting and re-sewing the less worn outsides to form the middle. Until rationing was stopped in 1952 our allowance of clothing coupons, just over a hundred a year, made people thrifty and careful to re-knit jumpers which had been unpicked for the wool, and to save and cut down old suits.

Kids wore smaller versions of what their parents wore. Mum kept and stored everything that could be re-sewed or adapted for other use, and as a child I had just three sets of clothes, one for school, one for play, and one best suit. I ached for more grown-up clothes. Tea, meat, butter, sugar and footwear: all, too, were rationed.

No dishwasher, no washing machine: Mum did everything on her own. She never had a big wardrobe, and didn’t have many clothes. Yet as she worked in a store drapery department, and was the boss’s secretary, we always had these lovely materials around the home which she’d make into costumes for me, tasteful wallpaper or decorations, and plenty of knick-knacks, although these were rather kitsch. Otherwise there were net curtains in the front room to stop people looking in, and rich drapes. Very house proud, very clean, and while she was out at work during the day Mum worked hard in the home, but now when I look back I can see she was a terrible cook.

Dad and I would never complain, but her best shot was cooking a joint for Sunday lunch. Her Sunday roast was passable, although well done – and it would always be very well done. Later I would be able to say that she couldn’t ‘nuance’ a rare steak. For her it was just meat, and whatever the meat was – lamb, beef, pork – it came out the same. I remember her omelettes were always open, like Spanish ones, large and on the leathery side. Sunday afternoon teas were of tinned salmon, spam, cucumber, radishes, bread and butter; altogether our food was plain and wholesome. She wasn’t interested in cooking; she didn’t have time to be interested.

Mum spoke, like Dad, with an East End accent, but was slightly more educated than he was. She had been to Hackney Cassland Road School, quite a good school near where my other grandmother lived, and she’d even learned to speak a bit of French.

I had only ever visited this granny once, as a very young child, when I had some flowers – a bunch of anemones – pressed into my hand to give her, and I was waiting outside the door.

‘Can I take my flowers in to Granny?’ I asked.

Mum said yes and I marched boldly in with them, and laid them beside Granny on the bed where she lay asleep.

I looked at Granny Lapland as she lay there. She seemed so peaceful and I did hope she would like my anemones.

There was a strange atmosphere in Granny’s room, as if time were standing still.

It was only later that I found out she was dead.

I knew from the age of six, when I dressed myself up in Mum’s wedding veil, that I was going to be an actor.

‘Do you know what you want to be when you grow up, Derek?’ I remember Mum asking me one day when I was older.

‘Oh yes, Mum, I know – I’ve always known. An actor.’

Would Mum and Dad mind, would they oppose me? It was a world they knew nothing about, nor did I.

‘Don’t you worry, dear, we’ll see you right. I’m sure you’ll land on your feet whatever you do.’

‘Oh well, it will be something different from your Dad and Uncle Henry – less boring perhaps – although as a chef Henry always fancies he’s a bit different from the run of the mill, don’t he?’

Henry was short and stocky, sandy-haired and freckled. He had a great sense of fun, and sometimes took risks, putting big money on horses and dogs. Later he’d take me with him to Walthamstow dog stadium, which was very exciting.

For a short time I joined the cubs and scouts, and once went to an annual camp. I remember with no affection sleeping in a tent in a famous scout park, being endlessly soaking wet, and loathing the communal life when we lived off things called ‘twists’ and ‘dampers’. We ate a sort of soup, which I suppose was chicken soup with barley, and which we made ourselves.

In the evening we sat around the campfire singing the usual ‘Ging Gang Goolie’ – ‘Ging gang goolie, goolie goolie goolie, watcha!’ – and being very silly. We played awful games like ‘British Bulldog’, when ten boys would be pitted against one, which was an excuse for a roughhouse. I am physically not very brave, so it didn’t suit me at all.

When I acted in plays as a child, I was always dressed up in all the ‘best frocks’, because Mum made or provided the costumes. It soon became apparent that, with Mum’s involvement, school was an extension of home and home an extension of school. She was outgoing, gregarious, chatty and quite extrovert, sometimes even flamboyant, and would speak her mind without inhibition. She could be very demonstrative. I was quite shocked later on when she met the famous actress Diana Wynyard in a car park opposite the Old Vic. She threw herself at her, and kissed her.

But there were other times when I heard her crying out in pain and anguish – though never directly in front of me, for she didn’t want me to know she was suffering from an illness I wasn’t supposed to be aware of. She would never complain how terrible the pain was. She tried to hide it, and sometimes she’d just go upstairs to be on her own. I was never taken up to see her.

Dad would ring up the doctor at once. Mum was careering round the room like a wounded animal, trying not to show pain, bumping into furniture, and never able to find relief, while Dad would prevail on her to sit down.

She’d had a mastoid operation before I was born, and the middle ear problems she suffered were recurrent. Our doctor visited us every week to examine her. He came every Wednesday and would give her medicine for them. During these terrible attacks she couldn’t stand, couldn’t lie down and lost all sense of balance. It was agonising for Dad to see and hear her when she was undergoing one of these attacks. I always feared she would die, for basically she was my rock, my comfort.

These problems became a nightmare: I couldn’t stand the idea of her attacks, nor could I help them. I had a complete lack of wanting to confront anything, and also a lack of responsibility, which was possibly a sign of how I was protected by Mum and Dad from some of the harsher realities of survival. It was all too evident with my childhood pets.

My first was a rabbit called Floppy; its cage was never cleaned unless my grandfather did it; likewise with my tropical fish aquarium. Then there was the tortoise which hibernated and never woke up. Finding this was horrible, for with a girl friend I went out into the garden to search, and when we did find it, its body had decomposed. The girl laughed, grabbed it and pushed it in my face to tease me – and that hurt me very much.

Dad grew vegetables and kept chickens, about a dozen. I loved to climb through the hatch into the dark henhouse, and savour being there all on my own, finding it oddly comforting to rest among the clucking of the hens. Certain aspects of life were quite rustic, but I was no good at looking after anything.

I have often since wondered why this was so, and I think it was because I was never very good at making decisions. For I was already the Boy with the Veil – this is what I fancied I was. The actor. And it remained so.

Actors have to keep one foot in the cradle. We must be open, like a child, and retain naïveté. I have plenty of the latter – or so my friends tell me – and have kept some of it, I think, from those early years.

I was born on the cusp of Libra, and as a result I am apparently a ‘triple Libran’. On the one hand I’m very well balanced, but on the other hand, hopeless at making up my mind. I tend to see both sides of everything and weigh everything equally, so choosing is difficult – and making my mind up is damn hard.

This means I dither, I’m always uncertain.

As a child, I don’t believe I thought about anything very much, and never philosophised, so some might say I was just shallow. Or you could say, which I suppose is truer, that I have always set more store by my intuition and imagination than by analytical thinking.

The only creative avenue I have ever walked down is acting.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/derek-jacobi/as-luck-would-have-it/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Derek Jacobi

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Кинематограф, театр

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 523.26 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Star of stage, screen and television, and one of only two people to be awarded two Knighthoods, Sir Derek Jacobi is one of Britain’s most distinguished actors.‘If you want to be an actor, don’t. If you need to be an actor, do.’The world of theatre could not have been further from Derek’s childhood: an only child, born in Leytonstone, London. With his father a department store manager and his mother a secretary, his was very much a working class background. But nonetheless Derek always knew he was going to be an actor, and he remembers clearly the first time he was in costume – draping himself in his mother’s glorious wedding veil as he paraded up and down the Essex Road with his friends.A few short years later, at the age of seven, Derek made his acting debut, playing both lead roles in a local library production of The Prince and the Swineherd. By the age of 18 Derek was playing Hamlet (his most famed role) at the Edinburgh festival. He won a scholarship to Cambridge, where he studied and acted alongside other future acting greats including Ian McKellen. His talent was quickly recognised and in 1963 he was invited to become one of the first members of Laurence Olivier’s National Theatre.Often admired for his willingness to grapple with even the most dislikeable of characters, Derek Jacobi has worked continuously throughout his career, starring in roles ranging from the lead in I, Claudius to Hitler in Inside the Third Reich and Francis Bacon in the controversial Love Is The Devil. But it is his numerous Shakespearean roles that have gained him worldwide recognition.This book is, however, much more than a career record. Funny, warm and honest, Jacobi brings us his insider’s view on the world of acting. From a simple childhood in the East End to the height of fame on stage and screen, Derek recalls his journey in full: from the beginnings of his childhood dreams to the legendary productions, the renowned stars and the intimate off-stage moments.