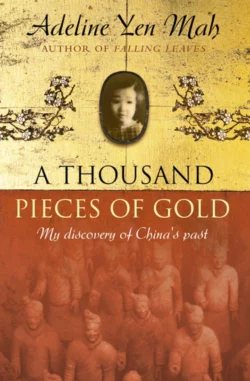

A Thousand Pieces of Gold: A Memoir of China’s Past Through its Proverbs

Adeline Mah

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1011.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The author of the international bestsellers Watching the Tree and Falling Leaves has always been fascinated by proverbs and their importance and use in China. Both her book titles are based on such proverbs.The majority of Chinese proverbs are drawn from the 1st century, when the First King of all China established his leadership over the whole country and its warring kingdoms. In ancient China, a scholar′s conversation would be studded with appropriate sayings, and a man′s status in society would be defined by his use and knowledge of proverbs. In modern China, much of this is still true, and proverbs are used daily.Adeline Yen Mah introduces us to the whole rich picture of the first century BC when after the long wars between states, China was finally united and the richness of the literature and art could flourish. She portrays the leaders, the plots and the counter-revolutions with great vividness and liveliness so that even those ignorant of Chinese history become absorbed. And as in all her other books, she relates the historical episodes and the proverbs derived from these to experiences in her own life.One of the major expressions of this age was of course the First King′s tomb with its terracotta soldiers, of horses and carriages and the stones of the building. The re-finding of this monument – now open to us all – and Adeline Yen Mah′s own experiences there, are extraordinary.A Thousand Pieces of Gold, following Watching the Tree and Falling Leaves, is a personal account by a much loved author, but it is also a lively history of the fascinating period of civilisation when Europe was barely out of the stone age.