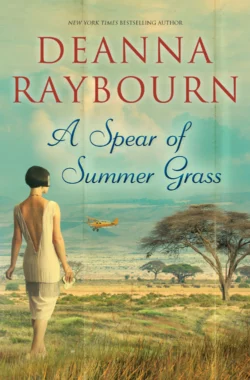

A Spear of Summer Grass

A Spear of Summer Grass

Deanna Raybourn

Don’t believe the stories you have heard about me. I have never killed anyone, and I have never stolen another woman’s husband.Oh, if I find one lying around unattended, I might climb on, but I never took one that didn’t want taking. And I never meant to go to Africa.“Raybourn expertly evokes late-nineteenth-century colonial India in this rollicking good read, distinguished by its delightful lady detective and her colorful family.” —Booklist on Dark Road to Darjeeling

Paris, 1923

The daughter of a scandalous mother, Delilah Drummond is already notorious, even amongst Paris society. But her latest scandal is big enough to make even her oft-married mother blanch. Delilah is exiled to Kenya and her favorite stepfather’s savannah manor house until gossip subsides.

Fairlight is the crumbling, sun-bleached skeleton of a faded African dream, a world where dissolute expats are bolstered by gin and jazz records, cigarettes and safaris. As mistress of this wasted estate, Delilah falls into the decadent pleasures of society.

Against the frivolity of her peers, Ryder White stands in sharp contrast. As foreign to Delilah as Africa, Ryder becomes her guide to the complex beauty of this unknown world. Giraffes, buffalo, lions and elephants roam the shores of Lake Wanyama amid swirls of red dust. Here, life is lush and teeming – yet fleeting and often cheap.

Amidst the wonders – and dangers – of Africa, Delilah awakes to a land out of all proportion: extremes of heat, darkness, beauty and joy that cut to her very heart. Only when this sacred place is profaned by bloodshed does Delilah discover what is truly worth fighting for – and what she can no longer live without. Don’t believe the stories you have heard about me.

I have never killed anyone, and I have never stolen another woman’s husband. Oh, if I find one lying around unattended, I might climb on, but I never took one that didn’t want taking.

And I never meant to go to Africa.

Praise for Deanna Raybourn

“With a strong and unique voice,

Deanna Raybourn creates unforgettable characters

in a richly detailed world. This is storytelling at its most compelling.”

—Nora Roberts, #1 New York Times bestselling author

“[A] perfectly executed debut… Deft historical detailing

[and] sparkling first-person narration.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review, on Silent in the Grave

“A riveting drama that makes page turning obligatory.

A very fine debut effort from Deanna Raybourn.”

—Bookreporter.com on Silent in the Grave

“A sassy heroine and a masterful, secretive hero. Fans of romantic mystery could ask no more – except the promised sequel.”

—Kirkus Reviews on Silent in the Grave

“This debut novel has one of the most clever endings I’ve seen.”

—Karen Harper, New York Times bestselling author,

on Silent in the Grave

“Deceptively civilized and proper, Silent in the Grave has undercurrents of nefarious deeds, secrets and my favorite, poisons.

An excellent debut novel.”

—Maria V. Snyder, author of Poison Study, on Silent in the Grave

“There are some lovely twists in the plot

and a most satisfactory surprise ending. I hope to read more

from Deanna Raybourn in time to come.”

—Valerie Anand, author of The Siren Queen

written under the name of Fiona Buckley, on Silent in the Grave

“Fans and new readers alike will welcome this sparkling sequel

to Raybourn’s debut Victorian mystery, Silent in the Grave…

the complex mystery, a delightfully odd collection of characters

and deft period details produce a rich and funny read.”

—Publishers Weekly on Silent in the Sanctuary

“Raybourn takes a leisurely approach to the meat of the

complex story, meticulously detailing the many colorful characters and creepy Victorian-era setting. But once the game’s afoot,

the pace picks up nicely. This is an excellent way

to while away a couple of cold evenings.”

—RT Book Reviews on Silent in the Sanctuary

“Following Silent in the Grave and Silent in the Sanctuary,

the newest book in the Lady Julia Grey series has a lot to measure up to’and it does.… A great choice for mystery,

historical fiction and/or romance readers.”

—Library Journal on Silent on the Moor

“Raybourn…delightfully evokes the language, tension

and sweeping grandeur of 19th-century gothic novels.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Dead Travel Fast

“Raybourn skillfully balances humor and earnest, deadly drama, creating well-drawn characters and a rich setting.”

—Publishers Weekly on Dark Road to Darjeeling

“Raybourn expertly evokes late-nineteenth-century colonial India

in this rollicking good read, distinguished by its

delightful lady detective and her colorful family.”

—Booklist on Dark Road to Darjeeling

“Beyond the development of Julia’s detailed world,

her boisterous family and dashing husband, this book

provides a clever mystery and unique perspective on the Victorian era through the eyes of an unconventional lady.”

—Library Journal on The Dark Enquiry

A Spear of Summer Grass

Deanna Raybourn

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For Valerie Gray, gifted editor and maker of magic.

I am a better writer for knowing you.

Contents

Chapter 1 (#u978884e7-438f-5a88-9e9a-4e0b612f04f2)

Chapter 2 (#uf1d82dbd-59f4-5867-aa86-269547c8c8c3)

Chapter 3 (#u1e0804dd-d0e4-5e58-ae25-b5d2276cea40)

Chapter 4 (#uaece5695-de9d-5bbe-9dbb-ad074142de39)

Chapter 5 (#ubaaeabed-684f-5816-a10f-261396b5f001)

Chapter 6 (#u4cbe643c-30dc-58b8-827f-6edb350680fa)

Chapter 7 (#ud7151884-051f-537a-996a-035e5bedc48c)

Chapter 8 (#uaaecec71-f0c2-5aef-974e-17d31933b8b3)

Chapter 9 (#u8804aa1d-068b-5434-9054-546c4396d7c2)

Chapter 10 (#uf90806d1-b4ed-54a5-83ec-26ddb893c640)

Chapter 11 (#ub690f275-50ae-56ae-9887-4db695722ab5)

Chapter 12 (#ub9e10336-ba65-5f1d-b30c-25160acef74b)

Chapter 13 (#u2b0c0e30-4b24-586c-842a-b00189e294c6)

Chapter 14 (#u30205f9a-7948-5036-9c1e-f1b100cc7fff)

Chapter 15 (#udeebfeff-46c3-587a-a8c2-5c4eb377e141)

Chapter 16 (#u84678c6b-1f08-534c-b4f8-4aec27a362de)

Chapter 17 (#uf3d15f39-27ba-5f81-a13f-de557da43399)

Chapter 18 (#u0e67cee8-e736-58dc-bc23-825236ca020d)

Chapter 19 (#u89af482b-c427-5532-948b-a3bde05e1250)

Chapter 20 (#u54dd7d37-c6ab-5337-a4f8-5da7472e102e)

Chapter 21 (#uf45299a5-9344-5718-b328-9f43ca37dec1)

Chapter 22 (#u33b05592-77a3-509c-b495-f25476796fbf)

Chapter 23 (#u2f6ecbb8-bfaf-5317-9835-3ed608ace9fe)

Chapter 24 (#u26a6899f-26d6-5087-bea9-2e63c2cf5006)

Chapter 25 (#u979aeaa7-38b5-54da-9e27-d5f83df4b022)

Acknowledgements (#u53aa5359-9765-5ac1-b3e7-3239eeeca77d)

Questions for Discussion (#u56ad6dac-50f6-52c9-9653-154d71804465)

1

Don’t believe the stories you have heard about me. I have never killed anyone, and I have never stolen another woman’s husband. Oh, if I find one lying around unattended, I might climb on, but I never took one that didn’t want taking. And I never meant to go to Africa. I blame it on the weather. It was a wretched day in Paris, grey and gloomy and spitting with rain, when I was summoned to my mother’s suite at the Hotel de Crillon. I had dressed carefully for the occasion, not because Mossy would care – my mother is curiously unfussy about such things. But I knew wearing something chic would make me feel a little better about the ordeal to come. So I put on a divine little Molyneux dress in scarlet silk with a matching cloche, topped it with a clever chinchilla stole and left my suite, boarded the lift and rode up two floors to her rooms.

My mother’s Swedish maid answered the door with a scowl.

“Good afternoon, Ingeborg. I hope you’ve been well?”

The scowl deepened. “Your mother is worried about you,” she informed me coldly. “And I am worried about your mother.” Ingeborg had been worrying about my mother since before I was born. The fact that I had been a breech baby was enough to put me in her black books forever.

“Oh, don’t fuss, Ingeborg. Mossy is strong as an ox. All her people live to be a hundred or more.”

Ingeborg gave me another scowl and ushered me into the main room of the suite. Mossy was there, of course, holding court in the centre of a group of gentlemen. This was nothing new. Since her debut in New Orleans some thirty years before she had never been at a loss for masculine attention. She was standing at the fireplace, one elbow propped on the marble mantelpiece, dressed for riding and exhaling a cloud of cigarette smoke as she talked.

“But that’s just not possible, Nigel. I’m afraid it simply won’t do.” She was arguing with her ex-husband, but you’d have to know her well to realise it. Mossy never raised her voice.

“What won’t do? Did Nigel propose something scandalous?” I asked hopefully. The men turned as one to look at me, and Mossy’s lips curved into a wide grin.

“Hello, darling. Come and kiss me.” I did as she told me to, swiftly dropping a kiss to one powdered cheek. But not swiftly enough. She nipped me sharply with her fingertips as I edged away. “You’ve been naughty, Delilah. Time to pay the piper, darling.”

I looked around the room, smiling at each of the gentlemen in turn. Nigel, my former stepfather, was a rotund Englishman with a florid complexion and a heart condition, and at the moment he looked about ten minutes past death. Quentin Harkness was there too, I was happy to see, and I stood on tiptoe to kiss him. Like Mossy, I’ve had my share of matrimonial mishaps. Quentin was the second. He was a terrible husband, but he’s a divine ex and an even better solicitor.

“How is Cornelia?” I asked him. “And the twins? Walking yet?”

“Last month actually. And Cornelia is fine, thanks,” he said blandly. I only asked to be polite and he knew it. Cornelia had been engaged to him before our marriage, and she had snapped him back up before the ink was dry on our divorce papers. But the children were sweet, and I was glad he seemed happy. Of course, Quentin was English. It was difficult to tell how he felt about most things.

I leaned closer. “How much trouble am I in?” I whispered. He bent down, his mouth just grazing the edge of my bob.

“Rather a lot.”

I pulled a face at him and took a seat on one of the fragile little sofas scattered about, crossing my legs neatly at the ankle just as my deportment teacher had taught me.

“Really, Miss Drummond, I do not think you comprehend the gravity of the situation at all,” Mossy’s English solicitor began. I struggled to remember his name. Weatherby? Enderby? Endicott?

I smiled widely, showing off Mossy’s rather considerable investment in my orthodontia.

“I assure you I do, Mr.—” I broke off and caught a flicker of a smile on Quentin’s face. Drat him. I carried on as smoothly as I could manage. “That is to say, I am quite sure things will come right in the end. I have every intention of taking your excellent advice.” I had learned that particular soothing tone from Mossy. She usually used it on horses, but I found it worked equally well with men. Maybe better.

“I am not at all certain of that,” replied Mr. Weatherby. Or perhaps Mr. Endicott. “You do realise that the late prince’s family are threatening legal action to secure the return of the Volkonsky jewels?”

I sighed and rummaged in my bag for a Sobranie. By the time I had fixed the cigarette into the long ebony holder, Quentin and Nigel were at my side, offering a light. I let them both light it – it doesn’t do to play favourites – and blew out a cunning little smoke ring.

“Oh, that is clever,” Mossy said. “You must teach me how to do it.”

“It’s all in the tongue,” I told her. Quentin choked a little, but I turned wide-eyed to Mr. Enderby. “Misha didn’t have family,” I explained. “His mother and sisters came out of Russia with him during the Revolution, but his father and brother were with the White Army. They were killed in Siberia along with every other male member of his family. Misha only got out because he was too young to fight.”

“There is the Countess Borghaliev,” he began, but I waved a hand.

“Feathers! The countess was Misha’s governess. She might be related, but she’s only a cousin, and a very distant one at that. She is certainly not entitled to the Volkonsky jewels.” And even if she were, I had no intention of giving them up. The original collection had been assembled over the better part of three centuries and it was all the Volkonskys had taken with them as they fled. Misha’s mother and sisters had smuggled them out of Russia by sewing them into their clothes, all except the biggest of them. The Kokotchny emerald had been stuffed into an unmentionable spot by Misha’s mother before she left the mother country, and nobody ever said, but I bet she left it walking a little funny. She had assumed – and rightly as it turned out – that officials would be squeamish about searching such a place, and with a good washing it had shone as brightly as ever, all eighty carats of it. At least, that was the official story of the jewels. I knew a few things that hadn’t made the papers, things Misha had entrusted to me as his wife. I would sooner set my own hair on fire than see that vicious old Borghaliev cow discover the truth.

“Perhaps that is so,” Mr. Endicott said, his expression severe, “but she is speaking to the press. Coming on the heels of the prince’s suicide and your own rather cavalier attitude towards mourning, the whole picture is a rather unsavoury one.”

I looked at Quentin, but he was studying his nails, an old trick that meant he wasn’t going to speak until he was good and ready. And poor Nigel just looked as if his stomach hurt. Only Mossy seemed indignant, and I smiled a little to show her I appreciated her support.

“You needn’t smile about it, pet,” she said, stubbing out her cigarette and lighting a fresh one. “Weatherby’s right. It is a pickle. I don’t need your name dragged through the mud just now. And Quentin’s practice is doing very well. Do you think he appreciates his ex-wife cooking up a scandal?”

I narrowed my eyes at her. “Darling, what do you mean you don’t need my name dragged through the mud just now? What do you have going?”

Mossy looked to Nigel who shifted a little in his chair. “Mossy has been invited to the wedding of the Duke of York to the Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon this month.”

I blinked. The wedding of the second in line to the throne was the social event of the year and one that ought to have been entirely beyond the pale for Mossy. “The queen doesn’t receive divorced women. How on earth did you manage that?”

Mossy’s lips thinned. “It’s a private occasion, not Court,” she corrected. “Besides, you know how devoted I have always been to the Strathmores. The countess is one of my very dearest friends. It’s terribly gracious of them to invite me to their daughter’s big day, and it would not do to embarrass them with any sort of talk.”

Ah, talk. The euphemism I had heard since childhood, the bane of my existence. I thought of how many times we had moved, from England to Spain to Argentina to Paris, and every time it was with the spectre of talk snapping at our heels. Mossy’s love affairs and business ventures were legendary. She could create more scandal by breakfast than most women would in an entire lifetime. She was larger than life, my Mossy, and in living that very large life she had accidentally crushed quite a few people under her dainty size-five shoe. She never understood that, not even now. She was standing in a hotel suite that cost more for a single night than most folks made in a year, and she could pay for it with the spare change she had in her pockets, but she would never understand that she had damaged people to get there.

Of course, she noticed it at once if I did anything amiss, I thought irritably. Let one of her marriages fail and it was entirely beyond her control, but if I got divorced it was because I didn’t try hard enough or didn’t understand how to be a wife.

“Don’t sulk, Delilah,” she ordered. “You are far too old to pout.”

“I am not pouting,” I retorted, sounding about fourteen as I said it. I sighed and turned back to the solicitor. “You see, Mr. Weatherby, people just don’t understand my relationship with Misha. Our marriage was over long before he put that bullet into his head.” Mr. Weatherby winced visibly. I tried again. “It was no surprise to Misha that I wanted a divorce. And the fact that he killed himself immediately after he received the divorce papers is not my fault. I even saw Misha that morning and stressed to him I wanted things to be very civil. I am friends with all of my husbands.”

“I’m the only one still living,” Quentin put in, rather unhelpfully, I thought.

I stuck out my tongue at him again and turned back to Mr. Weatherby. “As to the jewels, Misha’s mother and both sisters died in the Spanish flu outbreak in ’19. He inherited the jewels outright, and he gave them to me as a wedding gift.”

“They would have been returned as part of the divorce settlement,” Weatherby reminded me.

“There was no divorce,” I said, trumping him neatly. “Misha did not sign the papers before he died. I am therefore technically a widow and entitled to my husband’s estate as he died with neither a will nor issue.”

Mr. Weatherby took out a handkerchief and mopped his brow. “Be that as it may, Miss Drummond, the whole affair is playing out quite badly in the press. If you could only be more discreet about the matter, perhaps put on proper mourning or use your rightful name.”

“Delilah Drummond is my rightful name. I have never taken a husband’s name or title, and I never will. Frankly, I think it’s a little late in the day to start calling myself Princess Volkonsky.” Quentin twitched a little, but I ignored him. The truth was I had seen Mossy change her name more times than I could count on one hand, and it was hell on the linen and the silver. Far more sensible to keep a single monogram. “It’s a silly, antiquated custom,” I went on. “You men have been forcing us to change our names for the last four thousand years. Why don’t we switch it up? You lot can take our names for the next few millennia and see how you like it.”

“Stop her before she builds up a head of steam,” Mossy instructed Nigel. She hated it when I talked about women’s rights.

Nigel sat forward in his chair, a kindly smile wreathing his gentle features. “My dear, you know you have always held a special place in my affections. You are the nearest thing to a daughter I have known.”

I smiled back. Nigel had always been my favourite stepfather. His first wife had given him a pair of dull sons, and they had already been away at school when he married Mossy and we had gone to live at his country estate. He had enjoyed the novelty of having a girl about the place and never made himself a nuisance like some of the other stepfathers did. A few of them had actually tried on fatherhood for size, meddling in my schooling, torturing the governesses with questions about what I ate and how my French was coming along. Nigel just got on with things, letting me have the run of the library and kitchens as I pleased. Whenever he saw me, he always patted my head affectionately and asked how I was before pottering off to tend to his orchids. He taught me to shoot and to ride and how to back a winner at the races. I rather regretted it when Mossy left him, but it was typical of Nigel that he let her go without a fight. I was fifteen when we packed up, and on our last morning, when the cases were locked and stacked up in the hall and the house had already started to echo in a way I knew only too well, I asked him how he could just let her leave. He gave me his sad smile and told me they had struck a bargain when he proposed. He promised her that if she married him and later changed her mind, he wouldn’t stand in her way. He’d kept her for four years – two more than any of the others. I hoped that comforted him.

Nigel continued. “We have discussed the matter at length, Delilah, and we all agree that it is best for you if you retire from public life for a bit. You’re looking thin and pale, my dear. I know that is the fashion for society beauties these days,” he added with a melancholy little twinkle, “but I should so like to see you with roses in your cheeks again.”

To my horror, I felt tears prickling the backs of my eyes. I wondered if I was starting a cold. I blinked hard and looked away.

“That’s very kind of you, Nigel.” It was kind, but that didn’t mean I was convinced. I turned back, stiffening my resolve. “Look, I’ve read the newspapers. The Borghaliev woman has done her worst already. She’s a petty, nasty creature and she is spreading petty, nasty gossip which only petty, nasty people will listen to.”

“You’ve just described all of Paris society, dear,” Mossy put in. “And London. And New York.”

I shrugged. “Other people’s opinions of me are none of my business.”

Mossy threw up her hands and went to light another cigarette, but Quentin leaned forward, pitching his voice low. “I know that look, Delilah, that Snow Queen expression that means you think you’re above all this and none of it can really touch you. You had the same look when the society columnists fell over themselves talking about our divorce. But I’m afraid an attitude of noble suffering isn’t sufficient this time. There is some discussion of pressure being brought to bear on the authorities about a formal investigation.”

I paused. That was a horse of a different colour. A formal investigation would be messy and time-consuming and the press would lap it up like a cat with fresh cream.

Quentin carried on, his voice coaxing as he pressed his advantage. He always knew when he had me hooked. “The weather is vile and you know how you hate the cold. Why don’t you just go off and chase the sunshine and leave it with me? Your French lawyers and I can certainly persuade them to drop the matter, but it will take a little time. Why not spend it somewhere sunny?” he added in that same honeyed voice. His voice was his greatest asset as a solicitor and as a lover. It was how he had convinced me to go skinny-dipping in the Bishop of London’s garden pond the first night we met.

But he flicked a significant sideways glance at Mossy and I caught the thinning of her lips, the white lines at her knuckles as she held her cigarette. She was worried, far more than she was letting on, but somehow Quentin had persuaded her to let him handle me. Her eyes were fixed on the black silk ribbon I’d tied at my wrist. I had started something of a fashion with it among the smart set. Other women might wear lace or satin to match their ensembles, but I wore only silk and only black, and Mossy didn’t take her eyes off that scrap of ribbon as I rubbed at it.

I took another long drag off my cigarette and Mossy finally lost patience with me.

“Stop fidgeting, Delilah.” Her voice was needle-sharp and even she heard it. She softened her tone, talking to me as though I were a horse that needed soothing. “Darling, I didn’t want to tell you this, but I’m afraid you don’t really have a choice in the matter. I’ve had a cable from your grandfather this morning. It seems the Countess Borghaliev’s gossip has spread a little further than just Paris cafés. It made The Picayune. He is put out with you just now.” That I could well imagine. My grandfather – Colonel Beauregard L’Hommedieu of the 9th Louisiana Confederate Cavalry – was as wild a Creole as New Orleans had ever seen, but he expected the women in his family to be better behaved. He hadn’t had much luck with Mossy or with me, but he had no trouble pulling purse strings like a puppeteer to get his way.

“How put out?”

“He said if you don’t go away quietly, he will put a stop to your allowance.”

I ground out my cigarette, scattering ash on the white carpet. “But that’s extortion!”

She shrugged. “It’s his money, darling. He can do with it precisely as he likes. Anything you get from your grandfather is at his pleasure and right now it is his pleasure to have a little discretion on your part.” She was right about that. The Colonel had already drawn up his will and Mossy and I were out. He had a sizeable estate – town houses in the French Quarter, commercial property on the Mississippi, cattle ranches and cotton fields, and his crown jewel, Reveille, the sugar plantation just outside of New Orleans. And every last acre and steer and cotton boll was going to his nephew. There was a price to being notorious and Mossy and I were certainly going to pay it when the Colonel died. In the meantime, he was generous enough with his allowances, but he never gave without expecting something back. The better behaved we were, the more we got. The year I divorced Quentin, I hadn’t gotten a thin red dime, but since then he had come through handsomely. Still, feeling the jerk of the leash from three thousand miles away was a bit tiresome.

I felt the sulks coming back. “The Colonel’s money isn’t everything.”

“Very near,” Quentin murmured. It had taken him the better part of a year to untangle the mess of inheritances, annuities, alimonies and settlements that made up my portfolio and another year to explain exactly how I was spending far more than I got. With his help and a few clever investments, I had almost gotten myself into the black again. Most of my income still went to paying off the last of the creditors, and it would be a long time before I saw anything like a healthy return. The Colonel’s allowance kept me in Paris frocks and holidays in St. Tropez. Without it, I would have to economize – something I suspected I wouldn’t much enjoy.

I looked away again, staring out of the window, watching the rain hit the glass in great slashing ribbons. It was dismal out there, just as it had been in England. The last few months of 1922 had been gloomy and 1923 wasn’t off to much better of a start. Everywhere I went it was grey and bleak. As I watched, the raindrops turned to sleet, pelting the windows with a savage hissing sound. God, I thought miserably, why was I fighting to stay here?

“Fine. I’ll go away,” I said finally.

Mossy breathed an audible sigh of relief and even Weatherby looked marginally happier. I had cleared the first hurdle and the biggest; they had gotten me to agree to go. Now the only question was where to send me.

“America?” Quentin offered.

I slanted him a look. “Not bloody likely, darling.” Between the Volstead Act and the Sullivan Ordinance, I couldn’t drink or smoke in public in New York. It was getting harder and harder for a girl to have a good time. “I am protesting the intrusion of the federal government upon the rights of the individual.”

“Or are you protesting the lack of decent cocktails?” Quentin murmured.

“It’s true,” Mossy put in. “She won’t even travel on her American passport, only her British one.”

Quentin flicked a glance to Nigel. “I do think, Sir Nigel, perhaps your initial suggestion of Africa might be well worth revisiting.” So that’s what they’d been discussing when I had come in – Africa. At the mention of the word, Mossy started to kick up a fuss again and Nigel remonstrated gently with her. Mossy hated Africa. He’d taken her there for their honeymoon and she had very nearly divorced him over it. Something to do with snakes in the bed.

Nigel had gone to Africa as a young man, back in the days when it was a protectorate called British East Africa and nothing but a promise of what it might become someday. Then it was raw and young and the air was thick with possibilities. He had bought a tidy tract of land and built a house on the banks of Lake Wanyama. He called it Fairlight after the pink glow of the sunsets on the lake, and he had planned to spend the rest of his life there, raising cattle and painting. But his heart was bad, and on the advice of his doctors he left Fairlight, returning home with nothing but his thwarted plans and his diary. He never looked at it; he said it made him homesick for the place, which was strange since England was his home. But I used to go to his library and take it down sometimes, handling it with the same reverence a religious might show the Holy Grail. It was a mystical thing, that diary, bound with the skin of a crocodile Nigel had killed on his first safari. It was written in soft brown ink and full of sketches, laced with bones and beads and feathers and bits of eggshells – a living record of his time in Africa and of a dream that drew one good breath before it died.

The book itself wouldn’t shut, as if the covers weren’t big enough to hold the whole of Africa, and I used to sit for hours reading and tracing my finger along the slender blue line of the rivers, plunging my pinky into the sapphire pool of Lake Wanyama, rolling it up the high green slopes of Mt. Kenya. There were even little portraits of animals, some serene, some silly. There were monkeys gamboling over the pages, and in one exquisite drawing a leopard bowed before an elephant wearing a crown. There were tiny watercolour sketches of flowers so lush and colourful I could almost smell their fragrance on the page. Or perhaps it was from the tissue-thin petals, now crushed and brown, that Nigel had pressed between the pages. He conjured Africa for me in that book. I could see it all so clearly in my mind’s eye. I used to wish he would take us there, and I secretly hoped Mossy would change her mind and decide she loved Africa so I could see for myself whether the leopard would really bow down to the elephant.

But she never did, and soon after she packed us up and left Nigel and years passed and I forgot to dream of Africa. Until a sleety early April morning in Paris when I had had enough of newspapers and gossip and wagging tongues and wanted right away from everything. Africa. The very word conjured a spell for me, and I took a long drag from my cigarette, surprised to find my fingers trembling a little.

“All right,” I said slowly. “I’ll go to Africa.”

2

Quentin raised his glass of champagne. “A toast. To my brave and darling Delilah and all who go with her. Bon voyage!”

It was scarcely a fortnight later but all the arrangements had been made. Clothes had been ordered, trunks had been packed, papers procured. It sounds simple enough, but there had been endless trips to couturiers and outfitters and bookshops and stuffy offices for tickets and forms and permissions. By the end of it, I was exhausted, so naturally I chose to kick up my heels and make the most of my last evening in Paris. Quentin had guessed I would be feeling a little low and arranged to take me out. It had been a rather wretched day, all things considered. I had almost backed out of going to Africa a dozen times, but that morning Mossy appeared in my suite brandishing the latest copy of a scurrilous French newspaper that had somehow acquired photographs of Misha’s death scene. They dared not publish them, but the descriptions were gruesome enough, and they had taken lurid liberties with the prose as well.

“‘The Curse of the Drummonds,’” Mossy muttered. “How dare they! I’m no Drummond. I was married to Pink Drummond for about ten minutes sometime in 1891. I barely remember his face. If they want to talk about a curse on the women of our family, it ought to be the L’Hommedieu curse,” she finished, slamming the door behind her for emphasis.

With that I had given up all hope of avoiding exile and started pouring cocktails. I was only a little tight by the time Quentin picked me up, but he was lavish with the champagne, and when we reached the Club d’Enfer, I was well and truly lit.

I adored the Club d’Enfer. As one would expect from its name, it was modeled on Hell. The ceiling was hung with red satin cut into the shape of flames and crimson lights splashed everything with an unholy glow. A cunning little devil stood at the door greeting visitors by swishing his forked tail and poking at people’s bottoms with his pitchfork.

Quentin rubbed at his posterior. “I say, is that really necessary?”

“Oh, Quentin, don’t be wet,” I told him. “This place has swing.”

Behind us, my cousin Dora gave a little scream as the pitchfork prodded her derrière.

“Don’t bother,” I told the devil. “She’s English. You won’t find anything but bony disapproval there.”

“Delilah, really,” she protested, but I had stopped listening. A demonic waiter was waving us to a table near the stage, and Quentin ordered champagne before we were even seated.

Around us the music pulsed, a strange cacophonic melody that would have been grossly out of place anywhere else but suited the Club d’Enfer just fine.

As we sat, the proprietor approached. He – she? – was a curiously androgynous creature with the features of a woman but a man’s voice and perfectly-cut tuxedo. On the occasion of my first visit to the club, it had introduced itself as Regine and seemed to be neither male nor female. Or both. I had heard that Regine’s tastes ran to very hairy men or very horsey women, of which I was neither.

Regine bowed low over my hand, but then placed it firmly in the crook of his or her arm.

“My heart weeps, dear mademoiselle! I hear that Paris is about to lose one of the brightest stars in her firmament.”

Such flowery language was par for the course with Regine. I smiled a little wistfully.

“Yes, I am banished to Africa. Apparently I’ve been too naughty to be allowed to stay in Paris.”

“The loss is entirely that of Paris. And do you travel alone to the pais sauvage?”

“No. My cousin is coming. Regine, have you met Dora? Dora, say hello to Regine.”

Dora murmured something polite, but Regine’s eyes had kindled upon seeing her long, lugubrious features. “Another great loss for Paris.”

Dora dropped her head and I peered at her. “Dodo, are you blushing?”

“Of course not,” she snapped. “The lights are red.”

Regine shrugged. “A necessary artifice. One must believe one is truly a tourist in Hell at the Club d’Enfer.” With that, Dora received a kiss to the hand and blushed some more before Regine disappeared to order more champagne and some delicious little nibbles for us.

Quentin shook his head. “I must admit I’m a bit worried for you, Delilah. Africa won’t be anything like Paris, you know. Or New York. Or St. Tropez. Or even New Orleans.”

I sipped at the champagne, letting the lovely golden bubbles rush to my head on a river of exhilaration. “I will manage, Quentin. Nigel has provided me with letters of introduction and very sweetly made me a present of his best gun. I am well prepared.”

“Not the Rigby!” Quentin put in faintly.

“Yes, the Rigby.” It was the second gun I learned to shoot and the first I learned to love. Nigel had commissioned it before travelling to Africa, and it was a beautiful monster of a firearm – eleven pounds and a calibre big enough to drop an elephant.

Quentin shook his head. “Only Nigel would be sentimental enough to think a .416 is a suitable gun for a woman. Can you even lift it?”

“Lift it and fire it better than either of his sons. That’s why he gave it to me instead of them. They’ll be furious when they realise it’s gone.” I grinned.

“I can’t say as I blame them. It must have cost him the better part of a thousand pounds. I suppose you remembered ammunition?”

“Of course I did! Darling, stop fussing. I will be perfectly fine. After all, I have Dora to look after me,” I said with a nod toward where she sat poking morosely at a truffled deviled egg.

“Poor Dora,” Quentin observed, perhaps with a genuine tinge of regret. Quentin had always been sweetly fond of Dora in the way one might be fond of a slightly incontinent lapdog. The fact that she bore a striking resemblance to a spaniel did not help. She was dutiful and dull and had two interests in life – God and gardens. We were distant cousins, second or third – the branches of the Drummond family tree were hopelessly knotted. But she was a poor relation to my father’s people, and as such, was at the family’s beck and call whenever I required a chaperone. She had dogged me halfway around the world already, and I wondered if she were growing as tired of me as I was of her.

She looked up from her egg and smiled at Quentin as I went on. “Dora’s going to have the worst of it, I’m afraid. My lady’s maid quit when I told her we were going to Africa, and it didn’t seem worth the trouble to train a new one just to have her drop dead of cholera or get herself bitten by a cobra. So Dora is going to maid me as well as lend me an air of respectability.” She made a little sound of protest, but I kept talking. “I started her off at the salon. I dragged her to LaFleur’s and made Monsieur teach her how to cut my hair.” I might have been heading to the wilds of Africa, but there was no excuse to look untidy. My sleek black bob required regular and very precise maintenance, and Dora had been the natural choice to take on the job. I told her to think of it as a type of pruning or hedge control.

Quentin laughed out loud, a sure sign that the champagne was getting to him.

I fixed him with my most winsome expression. “You can do a favour for me while I’m away.”

“Anything,” was the prompt reply.

“I have garaged my car in London.” I reached into my tiny beaded bag and pulled out the key. I flipped it into his champagne glass. “Take her out and drive her once in a while.”

He stared at the key as the bubbles foamed around it. “The Hispano-Suiza? But it’s brand new!”

It was indeed. I’d only taken possession of it two months before. I had cooled my heels for half a year waiting for them to get the colour just right. I had instructed them to paint it the same scarlet as my lipstick, which the dealer couldn’t seem to understand until I had left a crimson souvenir of my kiss on the wall of his office. I had ordered it upholstered in leopard, and whenever I drove it I felt savagely stylish, a modern-day Boadicea in her chariot.

“That’s why I want it driven,” I told Quentin. “She’s like any female. If she sits around doing nothing for a year, she’ll rust up. And something that pretty deserves to be taken out for a ride and shown off.”

He fished into the glass and withdrew the key, wearing an expression of such wonder you’d have thought I just dropped the crown jewels into his lap. He dried the key carefully on his handkerchief and tucked it into his pocket. Cornelia wouldn’t like it, but I didn’t care and neither did Quentin.

Just then the Negro orchestra struck up a dance tune, something sensual and throbbing, and Quentin stood, holding out his hand to me. “Dance?” I rose and he smiled at Dora. “We’ll have the next one, shall we?”

Dora waved him off and I went into his arms. Quentin was a heavenly dancer, and there was something deliciously familiar about our bodies moving together.

“I have missed this, you know,” he said, his lips brushing my ear.

“Don’t, darling,” I said lightly. “Your mustache is tickling me.”

“You never complained before.”

“I never had the chance. I always meant to make you shave it off when we’d been married for a year.”

His arm tightened. The drums grew more insistent. “Sometimes I think I was a very great fool to let you go.”

“Don’t get nostalgic,” I told him firmly. “You are far better off with Cornelia. And you have the twins.”

“The twins are dyspeptic and nearsighted. They take after their mother.”

I laughed as he spun me into a series of complicated steps then swung me back into his arms. He felt solid under my touch. There had never been anything of the soft Englishman about Quentin. He was far too fond of cricket and polo for that.

I ran a happy hand over the curve of his shoulder and felt him shudder.

“Delilah, unless you plan on inviting me up for the night—”

He didn’t finish the sentence. He didn’t have to. We both knew I would. We’d spent more nights together since our divorce than we had during our marriage. Not when I was married to Misha, of course. That would have been entirely wrong. But it seemed very silly not to enjoy a quick roll in the hay when we both happened to be in the same city. After all, it wasn’t as though Cornelia had anything to fear from me. I had had him and I had let him go. I wasn’t about to take him back again. In fact, I rather thought I might be doing her a service. He was always jolly after a night with me; it must have made him easier to live with. Besides that, he was so lashed with guilt he invariably went home with an expensive present for Cornelia. I smiled up into Quentin’s eyes and wondered what she’d be getting this time. I had seen some divine little emerald clips in the Cartier window on the Rue de la Paix. I made a note to tell him about them.

We danced and the orchestra played on.

* * *

The next morning I waved goodbye to Paris through the haze of a modest hangover. Dora, who had restricted herself to two glasses of champagne, was appallingly chipper. Paris had dressed in her best to see us off. A warm spring sun peeked through the pearl-grey skirts of early morning fog, and a light breeze stirred the new leaves on the Champs-Élysées as if waving farewell.

“It might at least be bucketing down with rain,” I muttered irritably. I was further annoyed that Mossy had sent Weatherby to make certain I made the train to Marseilles. “Tell me, Mr. Weatherby, do you plan to come as far as Mombasa with us? Or do you trust us to navigate the Suez on our own?”

Weatherby wisely ignored the jibe. He handed over a thick morocco case stuffed with papers and bank notes. “Here are your travel documents, Miss Drummond, as well as a little travelling money from Sir Nigel in case you should meet with unexpected expenses. There are letters of introduction as well.”

I gave him a smile so thin and sharp I could have cut glass with it. “How perfectly Edwardian.”

Weatherby stiffened. “You might find it helpful to know certain people in Kenya. The governor, for instance.”

“Will I?”

He drew in a deep breath and seemed to make a grab for his patience. “Miss Drummond, I don’t think you fully comprehend the circumstances. Single women are not permitted to settle in Kenya. Sir Nigel took considerable pains to secure your entry. The governor himself issued permission.”

He brandished a piece of paper covered with official stamps. I peered at the signature. “Sir William Kendall.”

“As I say, the governor – and an old friend of your stepfather’s from his Kenya days. No doubt he will prove a useful connection in your new life in Kenya.”

I shoved the permit into the portfolio and handed it to Dora. “It’s very kind of Nigel to take so much trouble, but I don’t have a new life in Kenya, Mr. Weatherby. I am going for a short stay until everyone stops being so difficult about things. When the headlines have faded away, I’ll be back,” I told him. I would have said more, but just then there was a bit of a commotion on the platform. There was the sound of running footsteps, some jostling, and above it all, the baying of hounds hot on the scent.

“There she is!” It was the photographers, and before they could snap a decent picture, Weatherby had shoved me onto the train and slammed the door, very nearly stranding Dora on the platform. She fought her way onto the train, leaving the pack of reporters scrambling in her wake.

“Honestly,” Dora muttered. Her hat had somehow gotten crushed in the scrum and she was staring at it mournfully.

“Don’t bother trying to fix it, Dodo. It’s an improvement,” I told her. I moved to the window and let it down. Instantly, the photographers rushed the train, shouting and setting off flashbulbs. I gave them a mildly vulgar gesture and a wide smile. “Take all the pictures you want, boys. I’m headed to Africa!”

* * *

My high spirits had evaporated by the time we boarded the ship at Marseilles. I was no stranger to travel. I liked to keep on the move, one step ahead of everybody, heading wherever my whims carried me. What I resented was being told that I had to go. It was quite hurtful, really. Mossy had weathered any number of scandalous stories in the press and she’d never been exiled. Of course, none of her husbands had ever died in mysterious circumstances. She’d divorced all except my father, poor Peregrine Drummond, known to all and sundry as Pink. He’d gone off to fight in the Boer War just after their honeymoon without even knowing I was on the way. He had died of dysentery before lifting his rifle – a sad footnote to what Mossy said had been a hell of a life. He had been adventuresome and charming and handsome as the devil, and no one could quite believe that he had died puking into a bucket. It was a distinctly mundane way to go.

Since Mossy might well have been carrying the heir to the Drummond title, she’d spent her pregnancy sitting around at the family estate, waiting to pup. As soon as she went into labour, my father’s five brothers descended upon Cherryvale from London, pacing outside Mossy’s room until the doctor emerged with the news that the eldest of them was now the undisputed heir to their father’s title. Mossy told me she could hear the champagne corks and hushed whoops through the door. They needn’t have bothered to keep it down. If she’d been mother to the heir she’d have been forced to stay at Cherryvale with her in-laws. Since I was a girl – and of no particular interest to anyone – she was free to go. The prospect of leaving thrilled her so much she would have happily bought them a round of champagne herself.

As it was, she packed me up as soon as she could walk and we decamped to a suite at the Savoy with Ingeborg and room service to look after us. Mossy never returned to Cherryvale, but I went back for school holidays while my grandparents were alive. They spent most of their time correcting my posture and my accent. I eventually stopped slouching thanks to enforced hours walking the long picture gallery at Cherryvale with a copy of Fordyce’s Sermons on my head, but the long Louisiana drawl that had made itself at home on my tongue never left. It got thicker every summer when I went back to Reveille, but mellowed each school term when the girls made fun of me and I tried to hide it. I never did get the hang of those flat English vowels, and I eventually realised it was just easier to pummel the first girl who mocked me. I was chucked out of four schools for fighting, and Mossy despaired of ever making a lady of me.

But I did master the social graces – most of them anyway – and I made my debut in London in 1911. Mossy had been barred from Court on account of her divorces and it was left to my Drummond aunt to bring me out properly. She did it with little grace and less enthusiasm, and I suspected some money might have changed hands. But I fixed my fancy Prince of Wales feathers to my hair and rode to the palace in a carriage and made my double curtsey to the king and queen. The next night I went to my first debutante ball and two days later I eloped with a black-haired boy from Devonshire whose family almost disowned him for marrying an American with nothing but scandal for a dowry.

Johnny didn’t care. All he wanted was me, and since all I wanted was him, it worked out just fine. The Colonel came through with a handsome present of cash and Johnny had a little family money. He wanted to write, so I bought him a typewriter as a wedding present and he would sit at our little kitchen table pecking away as I burned the chops. He read me his articles and bits of his novel every evening as I eventually figured out how not to scorch things, and by the time his book was finished, I had even learned to make a proper soufflé. We were proud of each other, and everything we did seemed new, as if it was the first time it had ever been done. Whether it was sex or prose or jam on toast, we invented it. There was something fine about our time together, and when I took the memories out to look at them, I peered hard to find a shadow somewhere. Did the mirror crack when I sat on the edge of the bathtub and watched him shave? Did I spill salt when I fixed his eggs? Did an owl come to roost in the rafters of the attic? I had been brought up on omens, nursed on portents. Not from Mossy. She was a new creation, a modern woman, although I had spied her telling her rosary when she didn’t think I saw.

But there were the others. The Colonel’s withered old mother, Granny Miette, her keeper Teenie, and Teenie’s daughter, Angele. They were the guardians of my childhood summers at Reveille, and they kept the old ways. They knew that not everything is as it seems and that if you look closely enough, you can see the shadows of what’s to come in the bright light of your own happiness. Time is slower in Louisiana, each minute dripping past like cold molasses. Plenty of time to see if you want to and you know where to look.

I never looked in those days with Johnny. When I opened a closet and something fluttered out of the corner of my eye, I told myself it was just moths and nothing more, and I hung lavender and cedar to drive them away. When I peered in a cupboard and saw a shadow scurry past, I said it was mice and bought a cat, the meanest mouser I could find. I sent to Reveille for golden strands of vetiver and carried the dry grass in a small bundle in my pocket. It was the scent of sunlight and home, pungent and earthy and cedar-green-smelling, and I sewed a handful of it in the uniform that Johnny put on in 1914.

The uniform came back – or at least pieces of it did. Germans blew him to bits during the Battle of the Marne, and I don’t remember much of what happened after that. A black curtain has fallen over that time, and I don’t ever pull it back to look behind. It’s a place I don’t visit in my memories, and it was a long while before I came out of it. When I emerged, I chopped off my hair and hemmed up my skirts and set out to see what I’d been missing in the world. It had been an interesting ride, no doubt about it, but things had gotten a little out of hand to land me with banishment to Africa. I had handled my affairs with style and even a little discretion from time to time. But the world could be a hard place on a girl who was just out for a little fun, and I felt mightily put upon as the train churned into the station at Marseilles.

At the sight of the ship, my spirits perked right up. I had had a choice of sailing with a British outfit or later with a German one, but I had refused point blank to cross to Mombasa with a bunch of Krauts. I was still holding a bit of a grudge over Johnny and wasn’t inclined to give them a penny of my money. Sailing a week earlier meant missing the closing of Cocteau’s Antigone, but I was not about to budge. And when I saw the crew, I didn’t even mind giving up the Chanel costumes or the Picasso sets. The boys were absolutely darling, each and every one of them, and for the next fortnight, I nursed my grievances in style. The deck steward made certain my chair was always in the best spot, near the sun but comfortably shaded as we moved south. As soon as I settled myself each morning, he was there with a travelling rug and a cup of hot bouillon. The dining steward dampened my tablecloth lightly so my plate wouldn’t slide in rough seas and the wine wouldn’t spill on my French silks. The older officers took turns escorting me onto the dance floor, and the younger ones gathered up empty bottles by the armful. We composed messages to seal inside, each one sillier than the last, and hurled them overboard until the captain put a stop to it. But he made up for it by inviting me to sit at his table for the rest of the voyage, and I discovered he was the best dancer of the lot. Poor Dodo was violently seasick and spent the entire trip holed up in her cabin with a basin between her knees and a compress on her brow.

I was feeling much better indeed by the time we sailed into Mombasa, past the old Portuguese fort of St. Jesus. I had asked the officers endless questions about the place and they talked over each other until I scarcely got a word in edgewise. I learned quite a bit about Mombasa, although my knowledge was rather limited to places that might appeal to sailors. If I needed a tipple or a tattoo or a two-dollar whore, I knew just the spots, but five-star hotels seemed in short supply. They told me if we sailed into port early in the morning, I could make straight for Nairobi on the noon train, heading up-country to where the white settlers had carved out a settlement for themselves. The captain had an uncle who had gone up-country and he regaled me with tales of hippos in the gardens and leopards in the trees. I knew a bit from Nigel’s stories as well, but the captain’s knowledge was somewhat fresher and he offered me his guidebook as a reference.

“Be careful with the natives,” he warned. “Don’t let them take advantage of you. If you need advice, find an Englishman who’s been there and knows the drill. Make sure you visit the club in Nairobi. It’s the best place to get a bit of society and all the news. They won’t let you join, naturally, since you are a lady, but you would be permitted inside as the guest of a member. You will want to mix with your own kind, of course, but mind you steer clear of politics.”

“Politics! In a backwater like this?” I teased.

The captain had lovely eyes, but the expression in them was so serious it dampened the effect. “Definitely. Rhodesia gained its independence from the Crown last year, and there are those who feel that Kenya ought to be next.”

“And will England let her go as easily as she did Rhodesia?”

A slight furrow plowed its way between his brows. “Difficult to say. You see, England doesn’t care about Africa itself, not really. It’s all about control of the Suez.” He flipped open the guidebook and pointed on the map. “France, England and Germany have all established colonies in Africa to keep a close eye upon the Suez. At present, we have the advantage,” he said with a tinge of British pride, “but we may not keep it. It all depends on Whitehall and how nervous they are about India.” He traced a line from India westward, through the Arabian Sea, into the Gulf of Aden and then a sharp turn up the slender length of the Red Sea to the Suez at the tip of Egypt. “See there? Whoever controls Egypt controls the Suez, and through it, all the riches of India.”

I picked up the long slender line of the Nile. One branch, the Blue, curved into Ethiopia, but the other snaked through Uganda and trailed off somewhere beyond. “And whoever controls the Nile controls Egypt.”

“They do,” he conceded. “For now, we Brits control Egypt and the Suez is safe, but matters could change if the ultimate source of the White Nile is discovered to be in hostile territory.”

“Reason enough for England to hold onto Kenya,” I observed.

“Not just that,” he said, slowly folding up the map. “England has an obligation to the Indians who have come to settle here.”

“Indians? In Kenya?”

“Thousands,” he said grimly. “Now, they did their part during the war and no doubt about it. But one cannot deny that it has complicated matters here to no end. They are agitating for the right to own land, and some at Whitehall are inclined to give it them.”

“That can’t make the white colonists very happy.”

“Tensions are running high, and you’d do well to avoid any appearance of taking sides. Not that anyone would expect so lovely a lady to trouble herself with such things,” he added. I was a little surprised at his gallantry.

“Now, don’t you even think of flirting with me,” I warned him with a light tap to the arm. “I know you have a wife back in Southampton.”

He gave me a rueful smile. “That I do. But I can still appreciate innocent and congenial company.”

“So long as we both understand that the company will remain innocent,” I returned with an arch glance.

He laughed and freshened my drink. “My vessel and myself are at your disposal, Miss Drummond. How may we amuse you?”

I cocked my head to the side and pretended to think. “I would like to steer the ship.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/deanna-raybourn/a-spear-of-summer-grass/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Deanna Raybourn

Don’t believe the stories you have heard about me. I have never killed anyone, and I have never stolen another woman’s husband.Oh, if I find one lying around unattended, I might climb on, but I never took one that didn’t want taking. And I never meant to go to Africa.“Raybourn expertly evokes late-nineteenth-century colonial India in this rollicking good read, distinguished by its delightful lady detective and her colorful family.” —Booklist on Dark Road to Darjeeling

Paris, 1923

The daughter of a scandalous mother, Delilah Drummond is already notorious, even amongst Paris society. But her latest scandal is big enough to make even her oft-married mother blanch. Delilah is exiled to Kenya and her favorite stepfather’s savannah manor house until gossip subsides.

Fairlight is the crumbling, sun-bleached skeleton of a faded African dream, a world where dissolute expats are bolstered by gin and jazz records, cigarettes and safaris. As mistress of this wasted estate, Delilah falls into the decadent pleasures of society.

Against the frivolity of her peers, Ryder White stands in sharp contrast. As foreign to Delilah as Africa, Ryder becomes her guide to the complex beauty of this unknown world. Giraffes, buffalo, lions and elephants roam the shores of Lake Wanyama amid swirls of red dust. Here, life is lush and teeming – yet fleeting and often cheap.

Amidst the wonders – and dangers – of Africa, Delilah awakes to a land out of all proportion: extremes of heat, darkness, beauty and joy that cut to her very heart. Only when this sacred place is profaned by bloodshed does Delilah discover what is truly worth fighting for – and what she can no longer live without. Don’t believe the stories you have heard about me.

I have never killed anyone, and I have never stolen another woman’s husband. Oh, if I find one lying around unattended, I might climb on, but I never took one that didn’t want taking.

And I never meant to go to Africa.

Praise for Deanna Raybourn

“With a strong and unique voice,

Deanna Raybourn creates unforgettable characters

in a richly detailed world. This is storytelling at its most compelling.”

—Nora Roberts, #1 New York Times bestselling author

“[A] perfectly executed debut… Deft historical detailing

[and] sparkling first-person narration.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review, on Silent in the Grave

“A riveting drama that makes page turning obligatory.

A very fine debut effort from Deanna Raybourn.”

—Bookreporter.com on Silent in the Grave

“A sassy heroine and a masterful, secretive hero. Fans of romantic mystery could ask no more – except the promised sequel.”

—Kirkus Reviews on Silent in the Grave

“This debut novel has one of the most clever endings I’ve seen.”

—Karen Harper, New York Times bestselling author,

on Silent in the Grave

“Deceptively civilized and proper, Silent in the Grave has undercurrents of nefarious deeds, secrets and my favorite, poisons.

An excellent debut novel.”

—Maria V. Snyder, author of Poison Study, on Silent in the Grave

“There are some lovely twists in the plot

and a most satisfactory surprise ending. I hope to read more

from Deanna Raybourn in time to come.”

—Valerie Anand, author of The Siren Queen

written under the name of Fiona Buckley, on Silent in the Grave

“Fans and new readers alike will welcome this sparkling sequel

to Raybourn’s debut Victorian mystery, Silent in the Grave…

the complex mystery, a delightfully odd collection of characters

and deft period details produce a rich and funny read.”

—Publishers Weekly on Silent in the Sanctuary

“Raybourn takes a leisurely approach to the meat of the

complex story, meticulously detailing the many colorful characters and creepy Victorian-era setting. But once the game’s afoot,

the pace picks up nicely. This is an excellent way

to while away a couple of cold evenings.”

—RT Book Reviews on Silent in the Sanctuary

“Following Silent in the Grave and Silent in the Sanctuary,

the newest book in the Lady Julia Grey series has a lot to measure up to’and it does.… A great choice for mystery,

historical fiction and/or romance readers.”

—Library Journal on Silent on the Moor

“Raybourn…delightfully evokes the language, tension

and sweeping grandeur of 19th-century gothic novels.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Dead Travel Fast

“Raybourn skillfully balances humor and earnest, deadly drama, creating well-drawn characters and a rich setting.”

—Publishers Weekly on Dark Road to Darjeeling

“Raybourn expertly evokes late-nineteenth-century colonial India

in this rollicking good read, distinguished by its

delightful lady detective and her colorful family.”

—Booklist on Dark Road to Darjeeling

“Beyond the development of Julia’s detailed world,

her boisterous family and dashing husband, this book

provides a clever mystery and unique perspective on the Victorian era through the eyes of an unconventional lady.”

—Library Journal on The Dark Enquiry

A Spear of Summer Grass

Deanna Raybourn

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For Valerie Gray, gifted editor and maker of magic.

I am a better writer for knowing you.

Contents

Chapter 1 (#u978884e7-438f-5a88-9e9a-4e0b612f04f2)

Chapter 2 (#uf1d82dbd-59f4-5867-aa86-269547c8c8c3)

Chapter 3 (#u1e0804dd-d0e4-5e58-ae25-b5d2276cea40)

Chapter 4 (#uaece5695-de9d-5bbe-9dbb-ad074142de39)

Chapter 5 (#ubaaeabed-684f-5816-a10f-261396b5f001)

Chapter 6 (#u4cbe643c-30dc-58b8-827f-6edb350680fa)

Chapter 7 (#ud7151884-051f-537a-996a-035e5bedc48c)

Chapter 8 (#uaaecec71-f0c2-5aef-974e-17d31933b8b3)

Chapter 9 (#u8804aa1d-068b-5434-9054-546c4396d7c2)

Chapter 10 (#uf90806d1-b4ed-54a5-83ec-26ddb893c640)

Chapter 11 (#ub690f275-50ae-56ae-9887-4db695722ab5)

Chapter 12 (#ub9e10336-ba65-5f1d-b30c-25160acef74b)

Chapter 13 (#u2b0c0e30-4b24-586c-842a-b00189e294c6)

Chapter 14 (#u30205f9a-7948-5036-9c1e-f1b100cc7fff)

Chapter 15 (#udeebfeff-46c3-587a-a8c2-5c4eb377e141)

Chapter 16 (#u84678c6b-1f08-534c-b4f8-4aec27a362de)

Chapter 17 (#uf3d15f39-27ba-5f81-a13f-de557da43399)

Chapter 18 (#u0e67cee8-e736-58dc-bc23-825236ca020d)

Chapter 19 (#u89af482b-c427-5532-948b-a3bde05e1250)

Chapter 20 (#u54dd7d37-c6ab-5337-a4f8-5da7472e102e)

Chapter 21 (#uf45299a5-9344-5718-b328-9f43ca37dec1)

Chapter 22 (#u33b05592-77a3-509c-b495-f25476796fbf)

Chapter 23 (#u2f6ecbb8-bfaf-5317-9835-3ed608ace9fe)

Chapter 24 (#u26a6899f-26d6-5087-bea9-2e63c2cf5006)

Chapter 25 (#u979aeaa7-38b5-54da-9e27-d5f83df4b022)

Acknowledgements (#u53aa5359-9765-5ac1-b3e7-3239eeeca77d)

Questions for Discussion (#u56ad6dac-50f6-52c9-9653-154d71804465)

1

Don’t believe the stories you have heard about me. I have never killed anyone, and I have never stolen another woman’s husband. Oh, if I find one lying around unattended, I might climb on, but I never took one that didn’t want taking. And I never meant to go to Africa. I blame it on the weather. It was a wretched day in Paris, grey and gloomy and spitting with rain, when I was summoned to my mother’s suite at the Hotel de Crillon. I had dressed carefully for the occasion, not because Mossy would care – my mother is curiously unfussy about such things. But I knew wearing something chic would make me feel a little better about the ordeal to come. So I put on a divine little Molyneux dress in scarlet silk with a matching cloche, topped it with a clever chinchilla stole and left my suite, boarded the lift and rode up two floors to her rooms.

My mother’s Swedish maid answered the door with a scowl.

“Good afternoon, Ingeborg. I hope you’ve been well?”

The scowl deepened. “Your mother is worried about you,” she informed me coldly. “And I am worried about your mother.” Ingeborg had been worrying about my mother since before I was born. The fact that I had been a breech baby was enough to put me in her black books forever.

“Oh, don’t fuss, Ingeborg. Mossy is strong as an ox. All her people live to be a hundred or more.”

Ingeborg gave me another scowl and ushered me into the main room of the suite. Mossy was there, of course, holding court in the centre of a group of gentlemen. This was nothing new. Since her debut in New Orleans some thirty years before she had never been at a loss for masculine attention. She was standing at the fireplace, one elbow propped on the marble mantelpiece, dressed for riding and exhaling a cloud of cigarette smoke as she talked.

“But that’s just not possible, Nigel. I’m afraid it simply won’t do.” She was arguing with her ex-husband, but you’d have to know her well to realise it. Mossy never raised her voice.

“What won’t do? Did Nigel propose something scandalous?” I asked hopefully. The men turned as one to look at me, and Mossy’s lips curved into a wide grin.

“Hello, darling. Come and kiss me.” I did as she told me to, swiftly dropping a kiss to one powdered cheek. But not swiftly enough. She nipped me sharply with her fingertips as I edged away. “You’ve been naughty, Delilah. Time to pay the piper, darling.”

I looked around the room, smiling at each of the gentlemen in turn. Nigel, my former stepfather, was a rotund Englishman with a florid complexion and a heart condition, and at the moment he looked about ten minutes past death. Quentin Harkness was there too, I was happy to see, and I stood on tiptoe to kiss him. Like Mossy, I’ve had my share of matrimonial mishaps. Quentin was the second. He was a terrible husband, but he’s a divine ex and an even better solicitor.

“How is Cornelia?” I asked him. “And the twins? Walking yet?”

“Last month actually. And Cornelia is fine, thanks,” he said blandly. I only asked to be polite and he knew it. Cornelia had been engaged to him before our marriage, and she had snapped him back up before the ink was dry on our divorce papers. But the children were sweet, and I was glad he seemed happy. Of course, Quentin was English. It was difficult to tell how he felt about most things.

I leaned closer. “How much trouble am I in?” I whispered. He bent down, his mouth just grazing the edge of my bob.

“Rather a lot.”

I pulled a face at him and took a seat on one of the fragile little sofas scattered about, crossing my legs neatly at the ankle just as my deportment teacher had taught me.

“Really, Miss Drummond, I do not think you comprehend the gravity of the situation at all,” Mossy’s English solicitor began. I struggled to remember his name. Weatherby? Enderby? Endicott?

I smiled widely, showing off Mossy’s rather considerable investment in my orthodontia.

“I assure you I do, Mr.—” I broke off and caught a flicker of a smile on Quentin’s face. Drat him. I carried on as smoothly as I could manage. “That is to say, I am quite sure things will come right in the end. I have every intention of taking your excellent advice.” I had learned that particular soothing tone from Mossy. She usually used it on horses, but I found it worked equally well with men. Maybe better.

“I am not at all certain of that,” replied Mr. Weatherby. Or perhaps Mr. Endicott. “You do realise that the late prince’s family are threatening legal action to secure the return of the Volkonsky jewels?”

I sighed and rummaged in my bag for a Sobranie. By the time I had fixed the cigarette into the long ebony holder, Quentin and Nigel were at my side, offering a light. I let them both light it – it doesn’t do to play favourites – and blew out a cunning little smoke ring.

“Oh, that is clever,” Mossy said. “You must teach me how to do it.”

“It’s all in the tongue,” I told her. Quentin choked a little, but I turned wide-eyed to Mr. Enderby. “Misha didn’t have family,” I explained. “His mother and sisters came out of Russia with him during the Revolution, but his father and brother were with the White Army. They were killed in Siberia along with every other male member of his family. Misha only got out because he was too young to fight.”

“There is the Countess Borghaliev,” he began, but I waved a hand.

“Feathers! The countess was Misha’s governess. She might be related, but she’s only a cousin, and a very distant one at that. She is certainly not entitled to the Volkonsky jewels.” And even if she were, I had no intention of giving them up. The original collection had been assembled over the better part of three centuries and it was all the Volkonskys had taken with them as they fled. Misha’s mother and sisters had smuggled them out of Russia by sewing them into their clothes, all except the biggest of them. The Kokotchny emerald had been stuffed into an unmentionable spot by Misha’s mother before she left the mother country, and nobody ever said, but I bet she left it walking a little funny. She had assumed – and rightly as it turned out – that officials would be squeamish about searching such a place, and with a good washing it had shone as brightly as ever, all eighty carats of it. At least, that was the official story of the jewels. I knew a few things that hadn’t made the papers, things Misha had entrusted to me as his wife. I would sooner set my own hair on fire than see that vicious old Borghaliev cow discover the truth.

“Perhaps that is so,” Mr. Endicott said, his expression severe, “but she is speaking to the press. Coming on the heels of the prince’s suicide and your own rather cavalier attitude towards mourning, the whole picture is a rather unsavoury one.”

I looked at Quentin, but he was studying his nails, an old trick that meant he wasn’t going to speak until he was good and ready. And poor Nigel just looked as if his stomach hurt. Only Mossy seemed indignant, and I smiled a little to show her I appreciated her support.

“You needn’t smile about it, pet,” she said, stubbing out her cigarette and lighting a fresh one. “Weatherby’s right. It is a pickle. I don’t need your name dragged through the mud just now. And Quentin’s practice is doing very well. Do you think he appreciates his ex-wife cooking up a scandal?”

I narrowed my eyes at her. “Darling, what do you mean you don’t need my name dragged through the mud just now? What do you have going?”

Mossy looked to Nigel who shifted a little in his chair. “Mossy has been invited to the wedding of the Duke of York to the Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon this month.”

I blinked. The wedding of the second in line to the throne was the social event of the year and one that ought to have been entirely beyond the pale for Mossy. “The queen doesn’t receive divorced women. How on earth did you manage that?”

Mossy’s lips thinned. “It’s a private occasion, not Court,” she corrected. “Besides, you know how devoted I have always been to the Strathmores. The countess is one of my very dearest friends. It’s terribly gracious of them to invite me to their daughter’s big day, and it would not do to embarrass them with any sort of talk.”

Ah, talk. The euphemism I had heard since childhood, the bane of my existence. I thought of how many times we had moved, from England to Spain to Argentina to Paris, and every time it was with the spectre of talk snapping at our heels. Mossy’s love affairs and business ventures were legendary. She could create more scandal by breakfast than most women would in an entire lifetime. She was larger than life, my Mossy, and in living that very large life she had accidentally crushed quite a few people under her dainty size-five shoe. She never understood that, not even now. She was standing in a hotel suite that cost more for a single night than most folks made in a year, and she could pay for it with the spare change she had in her pockets, but she would never understand that she had damaged people to get there.

Of course, she noticed it at once if I did anything amiss, I thought irritably. Let one of her marriages fail and it was entirely beyond her control, but if I got divorced it was because I didn’t try hard enough or didn’t understand how to be a wife.

“Don’t sulk, Delilah,” she ordered. “You are far too old to pout.”

“I am not pouting,” I retorted, sounding about fourteen as I said it. I sighed and turned back to the solicitor. “You see, Mr. Weatherby, people just don’t understand my relationship with Misha. Our marriage was over long before he put that bullet into his head.” Mr. Weatherby winced visibly. I tried again. “It was no surprise to Misha that I wanted a divorce. And the fact that he killed himself immediately after he received the divorce papers is not my fault. I even saw Misha that morning and stressed to him I wanted things to be very civil. I am friends with all of my husbands.”

“I’m the only one still living,” Quentin put in, rather unhelpfully, I thought.

I stuck out my tongue at him again and turned back to Mr. Weatherby. “As to the jewels, Misha’s mother and both sisters died in the Spanish flu outbreak in ’19. He inherited the jewels outright, and he gave them to me as a wedding gift.”

“They would have been returned as part of the divorce settlement,” Weatherby reminded me.

“There was no divorce,” I said, trumping him neatly. “Misha did not sign the papers before he died. I am therefore technically a widow and entitled to my husband’s estate as he died with neither a will nor issue.”

Mr. Weatherby took out a handkerchief and mopped his brow. “Be that as it may, Miss Drummond, the whole affair is playing out quite badly in the press. If you could only be more discreet about the matter, perhaps put on proper mourning or use your rightful name.”

“Delilah Drummond is my rightful name. I have never taken a husband’s name or title, and I never will. Frankly, I think it’s a little late in the day to start calling myself Princess Volkonsky.” Quentin twitched a little, but I ignored him. The truth was I had seen Mossy change her name more times than I could count on one hand, and it was hell on the linen and the silver. Far more sensible to keep a single monogram. “It’s a silly, antiquated custom,” I went on. “You men have been forcing us to change our names for the last four thousand years. Why don’t we switch it up? You lot can take our names for the next few millennia and see how you like it.”

“Stop her before she builds up a head of steam,” Mossy instructed Nigel. She hated it when I talked about women’s rights.

Nigel sat forward in his chair, a kindly smile wreathing his gentle features. “My dear, you know you have always held a special place in my affections. You are the nearest thing to a daughter I have known.”

I smiled back. Nigel had always been my favourite stepfather. His first wife had given him a pair of dull sons, and they had already been away at school when he married Mossy and we had gone to live at his country estate. He had enjoyed the novelty of having a girl about the place and never made himself a nuisance like some of the other stepfathers did. A few of them had actually tried on fatherhood for size, meddling in my schooling, torturing the governesses with questions about what I ate and how my French was coming along. Nigel just got on with things, letting me have the run of the library and kitchens as I pleased. Whenever he saw me, he always patted my head affectionately and asked how I was before pottering off to tend to his orchids. He taught me to shoot and to ride and how to back a winner at the races. I rather regretted it when Mossy left him, but it was typical of Nigel that he let her go without a fight. I was fifteen when we packed up, and on our last morning, when the cases were locked and stacked up in the hall and the house had already started to echo in a way I knew only too well, I asked him how he could just let her leave. He gave me his sad smile and told me they had struck a bargain when he proposed. He promised her that if she married him and later changed her mind, he wouldn’t stand in her way. He’d kept her for four years – two more than any of the others. I hoped that comforted him.

Nigel continued. “We have discussed the matter at length, Delilah, and we all agree that it is best for you if you retire from public life for a bit. You’re looking thin and pale, my dear. I know that is the fashion for society beauties these days,” he added with a melancholy little twinkle, “but I should so like to see you with roses in your cheeks again.”

To my horror, I felt tears prickling the backs of my eyes. I wondered if I was starting a cold. I blinked hard and looked away.

“That’s very kind of you, Nigel.” It was kind, but that didn’t mean I was convinced. I turned back, stiffening my resolve. “Look, I’ve read the newspapers. The Borghaliev woman has done her worst already. She’s a petty, nasty creature and she is spreading petty, nasty gossip which only petty, nasty people will listen to.”

“You’ve just described all of Paris society, dear,” Mossy put in. “And London. And New York.”

I shrugged. “Other people’s opinions of me are none of my business.”

Mossy threw up her hands and went to light another cigarette, but Quentin leaned forward, pitching his voice low. “I know that look, Delilah, that Snow Queen expression that means you think you’re above all this and none of it can really touch you. You had the same look when the society columnists fell over themselves talking about our divorce. But I’m afraid an attitude of noble suffering isn’t sufficient this time. There is some discussion of pressure being brought to bear on the authorities about a formal investigation.”

I paused. That was a horse of a different colour. A formal investigation would be messy and time-consuming and the press would lap it up like a cat with fresh cream.