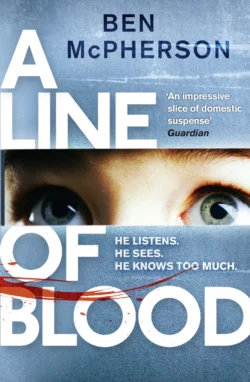

A Line of Blood

Ben McPherson

A chilling psychological thriller about family – the ties that bind us, and the lies that destroy us. Perfect for fans of The Girl on the Train and I Let You Go.You find your neighbour dead in his bath.Your son is with you. He sees everything.You discover your wife has been in the man’s house.It seems she knew him.Now the police need to speak to you.One night turns Alex Mercer’s life upside down. He loves his family and he wants to protect them, but there is too much he doesn’t know.He doesn’t know how the cracks in his and Millicent’s marriage have affected their son, Max. Or how Millicent’s bracelet came to be under the neighbour’s bed. He doesn’t know how to be a father to Max when his own world is shattering into pieces.Then the murder investigation begins…

Copyright (#u82410a4d-b0c1-5b6d-9557-69e18d851f44)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Copyright © Ben McPherson 2015

Ben McPherson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Cover photograph © Henry Steadman

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are

the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is

entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007569595

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN: 9780007569588

Version 2015-06-26

Praise for A Line of Blood (#u82410a4d-b0c1-5b6d-9557-69e18d851f44)

‘Ben McPherson has a very distinctive voice, and A Line of Blood is cleverly put together’ Val McDermid

‘Realistically flawed characters, and the ending is shocking’ Guardian

‘Ben McPherson drew me into the life of an ordinary family and gave me a ringside seat to watch the fracturing of those relationships beneath the weight of a murder investigation. Gripping from the get-go’ Tami Hoag, New York Times bestselling author

‘Fascinating. From the first page, I was hooked. I couldn’t put it down!’

Lisa Jackson, New York Times bestselling author

Dedication (#u82410a4d-b0c1-5b6d-9557-69e18d851f44)

For Charlotte

(#u82410a4d-b0c1-5b6d-9557-69e18d851f44)

Crappy is the name given by North Londoners to the very worst parts of Finsbury Park. People start using the name ironically, but it very quickly sticks.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u88c99686-f877-586f-9b3a-6ea2a3f10fee)

Title Page (#u0bbcfdc8-7c82-5105-a2a8-b2df846b1abc)

Copyright (#u44ccd667-e07b-55ad-8d86-04128b56af0f)

Praise for A Line of Blood (#ue5adebbc-a9ef-5ea1-9842-252d391a97ce)

Dedication (#u2bf55574-838f-55c5-8315-5fe53fd4f4cc)

Epigraph (#u929c95a5-285f-5706-8846-d2d9edb7c91e)

Part One: The Man Next Door (#ud9a0cd3c-a147-5e5a-806a-917a66a178b9)

Chapter 1 (#uefc0ac68-6b90-5ce4-8dfa-598f4b0ba9d7)

Chapter 2 (#u384a6787-6914-509a-a9eb-a597e3130413)

Chapter 3 (#u6d9b3e34-6a25-548c-9fce-e7906d6a2a55)

Chapter 4 (#ub6f42a45-c72b-59a8-9a40-d29733ba55b4)

Chapter 5 (#u3a4dfaad-f2b8-50f5-b6b6-19f1a5180e33)

Chapter 6 (#u2b50cad6-0ad0-5b24-bf7b-24c0a1358ab1)

Chapter 7 (#u5e9b73bc-55d6-5842-9727-67cc2b1291e6)

Chapter 8 (#u43da72d1-7763-53ec-9928-049adb61ed5f)

Part Two: Secrets, Shared With Another Girl (#u41898e91-1851-5d97-a70f-aca47d667ae9)

Chapter 9 (#u94b2743c-6a32-572f-8fcf-92ebac9b4e9e)

Chapter 10 (#u4d3d692f-27b5-506d-b24b-ace9d9da023c)

Chapter 11 (#u71b6cb10-d9ff-5909-aa63-c3d055350f01)

Chapter 12 (#ufa392a56-2541-53b8-8ae9-2c9aef9740f8)

Chapter 13 (#ub1755404-968c-5e2a-962e-2d82634b485b)

Chapter 14 (#u9ee56e5a-0420-5dee-81c7-60ec089db612)

Chapter 15 (#ua3f7c6dc-0479-53f2-b0a1-efb885283470)

Chapter 16 (#u4aecb045-310a-51db-9db6-0f0e0eea264a)

Chapter 17 (#u0ef0eeb4-64fb-5fac-b992-e887920dee1b)

Chapter 18 (#ua54922dc-7088-5b78-929c-ac6310bbe699)

Part Three: Manifest Destiny (#ubd35ef4a-72e1-5fe9-9782-5a9375e7c6fc)

Chapter 19 (#u04b3be75-8308-566d-8ae4-1382e88d21dd)

Chapter 20 (#uc17022b4-bfc8-5aec-9f08-04ecf9daef19)

Chapter 21 (#u65844986-b6b4-5274-8145-79a47184ba8c)

Chapter 22 (#ua1cc70c1-0ab0-5bb6-9fa5-cddd0cf72935)

Chapter 23 (#u17fdad3c-82c1-592b-a9a4-086f9c329e80)

Chapter 24 (#u26bc55b3-6367-5d51-8422-7796ffecffaa)

Chapter 25 (#ubab76193-30bf-5c97-ab5a-89d615366569)

Chapter 26 (#uccff7372-1365-5165-bf0d-84e5412d0cba)

Chapter 27 (#u34407050-15f0-5af8-a36b-b7d6d0f8c75e)

Chapter 28 (#u2313ea8d-52f4-5875-8d30-8ab68a12debf)

Chapter 29 (#ua17a7ac5-5a6a-5dde-a5b2-ddf81c62c2cc)

Chapter 30 (#u550640e8-2aef-5fca-acdb-2b68e54a07a1)

Chapter 31 (#uc0a19a97-e88e-5b10-a654-d6cbba83b009)

Acknowledgements (#u3849b969-fd1e-5ca3-9ac9-f51380cd2cff)

About the Author (#udd0338a2-88d7-550f-a1b0-eef788717099)

About the Publisher (#u21e5bd46-fe24-5672-8838-77475591aa83)

PART ONE (#u82410a4d-b0c1-5b6d-9557-69e18d851f44)

1 (#ulink_84f84a69-0271-5558-a266-f520be72b2e9)

The precarious thinness of his white arms, all angles against the dark foliage.

‘Max.’

Nothing. No response. He was half-hidden, straddling the wall, his body turned away from me. Listening, I thought. Waiting, perhaps.

‘Max.’

He turned now to look at me, then at once looked away, back at the next-door neighbour’s house.

‘Foxxa,’ he said quietly.

‘Max-Man. Bed time. Down.’

‘But Dad, Foxxa …’

‘Bed.’

Max shook his head without turning around. I approached the wall, my hand at the level of his thigh, and reached out to touch his arm. ‘She’ll come home, Max-Man. She always comes home.’

Max looked down at me, caught my gaze, then looked back towards the house next door.

‘What, Max?’

No response.

‘Max?’

Max lifted his leg over the wall and disappeared. I stood for a moment, unnerved.

In the early days of our life in Crappy we had bought a garden bench. A love seat, Millicent had called it, with room only for two. But Finsbury Park wasn’t the area for love seats. We’d long since decided it was too small, that the stiff-backed intimacy it forced upon us was unwelcome and oppressive, something very unlike love.

The love seat stood now, partly concealed by an ugly bush, further along the wall. Standing on it, I could see most of the next-door neighbour’s garden. It was as pitifully small as ours, but immaculate in its straight lines, its clearly delineated zones. A Japanese path led from the pond by the end wall to a structure that I’d once heard Millicent refer to as a bower, shaped out of what I guessed were rose bushes.

Max was standing on the path. He saw me and turned away, walking very deliberately into the bower.

‘Max.’

Nothing.

I stood on the arm of the love seat, and put my hands on top of the wall, pushing down hard as I jumped upwards. My left knee struck the head of a nail, and the pain almost lost me my balance.

I panted hard, then swung my leg over the wall and sat there as Max had, looking towards the neighbour’s house. Seen side by side, they were identical in every detail, except that the neighbour had washed his windows and freshened the paint on his back door.

A Japanese willow obscured the rest of the neighbour’s ground floor. A tree, a pond, a bower. Who builds a bower in Finsbury Park?

Max reappeared.

‘Dad, come and see.’

I looked about me. Was this trespass? I wasn’t sure.

Max disappeared again. No one in any of the other houses seemed to be looking. The only house that could see into the garden was ours. And I needed to retrieve my son.

I jumped down, landing badly and compounding the pain in my knee.

‘You aren’t supposed to say fuck, Dad.’

‘I didn’t say it.’ Did I?

‘You did.’

He had reappeared, and was looking down at me again, as I massaged the back of my knee, wondering if it would stiffen up.

‘And I’m allowed to say it. You are the one who isn’t.’

He smiled.

‘You’ve got a hole in your trousers.’

I nodded and stood up, ruffled his hair.

‘Does it hurt?’

‘Not much. A bit.’

He stared at me for a long moment.

‘All right,’ I said, ‘it hurts like fuck. Maybe I did say it.’

‘Thought so.’

‘Want to tell me what we’re doing here? Max-Man?’

He held out his hand. I took it, surprised, and he led me into the bower.

The neighbour had been busy here. Four metal trellises had been joined to make a loose arch, and up these trellises he had teased his climbing roses, if that’s what they were. Two people could have lain down in here, completely hidden from view. Perhaps they had. The grass was flattened, as if by cushions.

Now I noticed birdsong, distant-sounding, wrong, somehow.

Max crouched down, rubbed his right forefinger against his thumb.

From a place unseen, a small dark shadow, winding around his legs. Tortoiseshell, red and black. Max rubbed finger and thumb together again, and the cat greeted him, stood for a moment on two legs, teetering as she arched upwards towards his fingers, then fell forwards and on to her side, offering him her belly.

‘Foxxa.’

It was Max who had named the cat. He had spent hours with her, when she first arrived, whispering to her from across the room: F, K, Ks, S, Sh. He had watched how she responded to each sound, was certain he had found the perfect name.

‘Foxxa.’

The cat chirruped. Max held out his hand, and she rolled on to her back, cupped her paws over his knuckles, bumped her head gently into his hand.

‘Crazy little tortie,’ he whispered.

She tripped out of the bower. Crazy little tortie was right. We hadn’t seen her in days.

Max walked out of the bower and towards the patio. I followed him. The cat was not there.

From the patio, the pretentious absurdity of the bower was even more striking. The whole garden was no more than five metres long, four metres wide. The bower swallowed at least a third of the usable space, making the garden even more cramped than it must have been when the neighbour moved in.

The cat appeared from under a bush, darted across the patio. Too late I saw that the back door was ajar. She paused for a moment, looking back at us.

‘Foxxa, no!’ said Max.

Her tail curled around the edge of the door, then she had disappeared inside.

Max was staring at the back door. I wondered if the neighbour was there behind its wired glass panels, just out of view. Max approached the door, pushing it fully open.

‘Max!’

I lunged towards him, but he slipped into the kitchen, leaving me alone in the garden.

‘Hello?’ I shouted. I waited at the door but there was no reply.

‘Come on, Dad,’ said Max.

I found him in the middle of the kitchen, the cat at his feet.

‘Max, we can’t be in here. Pick her up. Let’s go.’

Max walked to the light switch and turned on the light. Thrill of the illicit. We shouldn’t be in here.

‘Max,’ I said, ‘out. Now.’

He turned, rubbed his thumb and forefinger together, and the cat jumped easily up on to the work surface, blinking back at us.

‘She likes it here.’

‘Max … Max, pick her up.’

Max showed no sign of having heard me. I could read nothing in his gestures but a certain stiff-limbed determination. He had never disobeyed me so openly before.

Light flooded the white worktops, the ash cupboard fronts, the terracotta floor tiles. It was all so clean, so bright, so without blemish. I thought of our kitchen, with its identical dimensions. How alike, yet how different. On the table was a pile of clean clothes, still in their wrappers. Two suits, a stack of shirts, all fresh from the cleaners. No two-day-old saucepans stood unwashed in the sink. No food rotted here, no cat litter cracked underfoot, no spider plants went short of water.

From the middle of the kitchen you could see the front door. The neighbour had moved a wall; or perhaps he hadn’t moved a wall; perhaps he had simply moved the door to the middle of his kitchen wall. Natural light from both sides. Clever.

Max left the room. I looked back to where the cat had been standing, but she was no longer there. I could hear him calling to her, a gentle clicking noise at the back of his throat.

I followed him into the living room. Max was already at the central light switch. Our neighbour had added a plaster ceiling rose, and an antique crystal chandelier, which hung too low, dominating the little room. The neighbour had used low-energy bulbs in the chandelier, and they flicked into life, sending ugly ovoids of light up the seamless walls. What was this? And where was the cat?

Max found a second switch, and the bottom half of the room was lit by bulbs in the floor and skirting.

‘Pick up the cat, Max-Man. Time to go.’

He made a gesture. Arms open, palm up. Then he held up his hand. Listen, he seemed to be saying, and listen I did. A dog; traffic; a rooftop crow. People walked past, voices low, their shoes scuffing the pavement.

These houses should have front yards, Millicent would say: it’s like people walking through your living room. You could hear them so clearly, all those bad kids and badder adults: the change in their pockets, the phlegm in their throats, the half-whispered street deals and the Coke-can football matches. It was all so unbearably close.

But there was something else too, a dull, rhythmic tapping that I couldn’t place, couldn’t decipher. Max had located it, though. He pointed to the brown leather sofa. A dark stain was spreading out across the central cushion.

I looked at Max. Max looked at me.

‘Water,’ said Max.

Water dripping on to the leather sofa. Yes, that was the sound. Max looked up. I looked up. The plaster of the ceiling was bowing. No crack was visible, but at the lowest point water was gathering: gathering and falling in metronomic drops, beating out time on the wet leather below.

Now I could see that cat. She was halfway up the staircase, watching the tracks of the water through the air.

Max and I looked at each other. I could read nothing in my son’s expression beyond a certain patient expectancy.

‘Maybe you should shout up to him, Dad. Case he’s here.’

Maybe I should. Maybe I should have shouted louder as I’d skulked by the back door, because standing here in his living room, looking up his stairs towards the first floor, it felt a little late to be alerting him to our presence.

‘Hello?’

Nothing.

‘It’s Alex. From next door.’

‘And Max,’ said Max quietly. ‘And Foxxa.’

‘Alex and Max,’ I shouted up. ‘We’ve come to get our cat.’

Nothing. Water falling against leather. Another street-dog. I looked again at Max.

‘You go first, Dad.’

He was right. I couldn’t send him upstairs in front of me. I had always suspected overly tidy men of having dark secrets in the bedroom.

‘Maybe he left a tap on,’ I said quietly.

‘Maybe.’ Max wrinkled his nose.

‘All right. Stay there.’

I saw the cat’s tail curl around a banister. I headed slowly up the stairs.

A click, and the landing light came on. Max had found that switch too.

Two rooms at the back, two at the front: just like ours. At the back the bathroom and the master bedroom, at the front the second bedroom and a tiny room that only estate agents called a bedroom. The cat was gone. The bathroom door was open.

The neighbour was in the bathtub, on his back, his legs and arms thrown out at discordant angles, as if something in his body was broken and couldn’t be repaired. His mouth was open, his lips were pulled back.

His eyes seemed held open by an unseen force; the left eye was shot through with blood. Blood was gathering around his nostrils too.

I did not retch, or cover my eyes, or cry, or any of the thousand things you’re supposed to do. Instead, and I say this with some shame, I heard and felt myself laugh. Perhaps it was the indignity of the half-erection standing proud from his lifeless body; perhaps it was simply my confusion.

I looked away from his penis, then back, and saw what prudishness had prevented me from seeing before. Lying calmly in the gap between the neighbour’s thighs was an iron. A Black and Decker iron. Fancy. Expensive. There were burn-marks around the top of his left thigh. The iron had been on when he had tipped it into the bath.

Did people really do this? The electric iron? The bath? Wasn’t it a teenage myth? Surely, you would think, surely the fuse would save you? Surely a breaker would have tripped?

Apparently not.

The bath had cracked. The neighbour must have kicked out so hard that he’d broken it. Some sort of fancy plastic composite. The bath would have drained quickly after that, but not quickly enough to save the neighbour from electrocution. Poor man.

‘Dad.’

Max. He was standing in the doorway, the cat in his arms. I hadn’t heard him climb the stairs. Oh please, no.

‘Is he dead?’

‘Out, Max.’ Surely this needs some sort of lie.

‘But Dad.’

‘Out. Downstairs. Now.’

‘But Dad. Dad.’

I turned to look at him.

‘What, Max?’

‘Are you OK, Dad?’ said Max, stepping out on to the landing. I looked at him again, his thin shoulders, his floppy hair, that unreadable look in his eyes. You’re eleven, I thought. When did you get so old?

‘Dad. Dad? Are you going to call the police?’

I nodded.

‘His phone’s downstairs in the living room.’

He was taking charge. My eleven-year-old son was taking charge. This had to stop. This couldn’t be good.

‘No, Max,’ I said, as gently as I could. ‘We’re going to go back to our place. I’ll call from there.’

‘OK.’ He turned and went downstairs.

I took a last look at the neighbour and wondered just what Max had understood. The erection was subsiding now; the penis lay flaccid on his pale thigh.

I heard Max open the front door. ‘You coming, Dad?’

I went home and rang the police and told them what we had found. Then I rang Millicent, though I knew she would not pick up.

Max and I sat at opposite sides of the table in our tired little kitchen, watching each other in silence.

After I had called the police I had made cheese sandwiches with Branston pickle. Max had done what he always did, opening his sandwiches, picking up the cheese and thoughtfully sucking off the pickle, stacking the cheese on his plate and the bread beside it. He had then eaten the cheese, stuffing it into his mouth, chewing noisily and swallowing before he could possibly be ready to. Normally I would have said something, and Max would have ignored it, and I would have shouted at him. Then, if Millicent had been with us, she would have shot me a furious glance, refused to speak to me until Max had gone to bed, then said, simply, ‘Why pick that fight, Alex, honey? You never win it anyway. You’re just turning food into a thing. Food doesn’t have to be a thing.’

Tonight I simply watched Max, wondering what to do, and what to tell Millicent when she came home.

A father leads his son from the world of the boy into the world of the man. A father takes charge, and does not without careful preparation expose his son to the cold realities of death. A father – more specifically – does not expose his son to the corpse of the next-door neighbour, and – most especially – not when that corpse displays an erection brought on by suicide through electrocution.

The tension in the limbs, that rictus smile, they were not easily erased. What did Max know about suicide? What could an eleven-year-old boy know about despair? I had to talk to him, but had no idea what to say. This was bad. Wasn’t this the stuff of full-blown trauma, of sexual dysfunction in the teenage years, and nervous breakdown in early adulthood? And though I hadn’t actively shown Max the neighbour, I had failed to prevent him from seeing him in all his semi-priapic squalor. What do you say? Maybe Millicent would know.

‘Can I have some more cheese, Dad?’

I said nothing.

Maybe I should ring Millicent again. The phone would go to voicemail, but there was comfort in hearing her voice.

Max went to the fridge and fetched a large block of cheddar, then took the bread knife from the breadboard. He sat back down at the table and looked directly at me, wondering perhaps why I’d done nothing to stop him. Then he cut off a large chunk. I noticed the bread knife cut into the surface of the table, but said nothing.

The cat was at the sink. She looked at Max, eyes large, then blinked.

Max went to the sink and turned on the tap. The cat drank, her tongue flicking in and out, curling around the stream of water.

‘Can I watch Netflix?’

I looked at my computer, at the light that pulsed gently on and off. No. Seventy hours of footage to watch, and a week to do it. I have to work.I really should say no.

‘Dad?’ said Max.

I nodded. Work seemed very distant now. Max stared.

‘I’m not taking a plate,’ he said at last.

‘OK.’

At eleven thirty I heard Millicent’s key in the lock. I was sitting where Max had left me at the kitchen table, my own sandwich untouched; the tap was still running.

I heard Millicent drop her bag at the foot of the stair. For the first time I noticed the sound of the programme on the computer: helicopters and gunfire; screaming and explosions. Millicent and Max exchanged soft words. The gunfire and the screaming stopped.

‘Night, Max.’

‘Night, Mum.’

The sound of Max going upstairs; the sound of Millicent dropping her shoes beside her bag.

‘So, Max is up kind of late.’ Millicent came into the kitchen. She stopped in the doorway for a moment, and I saw her notice Max’s plate, the stack of uneaten bread, the bread-knife cut in the table surface. She turned off the tap, then sat down opposite me. She made to say something, then frowned.

‘Hi,’ I said.

‘Hey.’ Her voice drew out the word, all honey and smoke.

When Millicent first came to London it had felt like our word. The long Californian vowel, the gently falling cadence at the end, were for me, and for me alone. Hey. There was such warmth in her voice, such love. In time I realised hey was how she greeted friends, that she had no friends in London but me at the start; the first time she said hey to another man the betrayal stung me. Don’t laugh at me for this. I didn’t know.

‘So,’ said Millicent. ‘I didn’t stink.’

I don’t know what you mean.

‘In fact, I think I did OK. I mean, I guess I talked a little too much, but it went good for a first time. Look.’

A bag. A bottle and some flowers. There’s a dead man in the next-door house.

I looked up at a dark mark in the wall near the ceiling. Round, like a target. Draw a straight line from me through that mark, and you’d hit the neighbour. Seven metres, I guessed. Maybe less.

Millicent looked at me, then reached out and took my hand in hers, turning it over and unclenching my fist.

‘You are super-tense.’

‘It’s OK.’

‘You’re OK?’

No. I was as far from OK as I could imagine but the words I needed wouldn’t form. ‘Yes,’ I said at last.

‘You forgot.’ It took a lot to hurt Millicent, but I could feel the edge of disappointment in her voice. The interview, on the radio. Of course.

‘No,’ I said. ‘Radio.’ Why can’t I find the words?

‘OK,’ she said. She looked at me as if I had run over a deer. ‘But you didn’t listen to it. I mean, it’s also a download, so I get that maybe it’s not time-critical, but I guess I was kind of hoping, Alex …’

I breathed deep, trying to decide how to say what I had to say. From the look of Millicent, Max had told her nothing of what we’d seen. I wondered where the police were. Maybe bathroom suicides were a common event around here. What do you say?

‘What is it, Alex?’

From upstairs I heard Max flush the toilet. I thought of the bathroom in the house next door, of the bath five metres from where he was now.

‘Alex?’

‘OK.’ I took Millicent’s hand in mine, looked her in the eye. ‘OK.’

‘You’re scaring me a little, Alex. What’s going on?’

Three sentences, I thought. Anything can be said in three sentences. You need to find three sentences.

‘OK. This is what I need to tell you.’

‘Yes?’

‘The neighbour killed himself. I found him. Max saw.’ Nine words. Not bad.

‘No,’ she said. Very quiet, almost matter-of-fact, as if refuting a badly phrased proposition. ‘No, Alex, he isn’t. He can’t be.’

‘I found him. Max saw.’ Five words.

She stared at me. Said nothing.

‘I should have stopped him from seeing. I didn’t.’

Still she stared at me. She brought her right hand up to her face, rubbing the bridge of her nose in the way she does when she’s buying time in an argument.

‘I haven’t talked to him yet about what he saw. I know I have to, but I wanted to talk to you first.’ Because you’re better at this than me. Because I don’t know what to say.

Still Millicent said nothing.

The doorbell rang. Millicent did not move. I did not move. It rang again. We sat there, staring at each other. Only when I heard footsteps on the stairs did I stand up and go to the front room. Max had the door open. He stood there in his lion pyjamas, looking up at the two policemen.

‘Upstairs, Max,’ I said, trying to smile at the policemen, aware suddenly of the papers strewn across the floor, of Millicent’s pizza carton and my beer cans on the side table. ‘I’ll be up in a minute, Max,’ I said, guiding him towards the stair.

‘It’s OK. Night, Dad.’ He kissed me and slipped away from my hand and up the stairs. I nodded at the policemen and was surprised by the warmth of their smiles.

We agreed that it would be easiest for them to enter the neighbour’s property through our back garden. Save breaking down the front door and causing unnecessary drama. Better to keep the other neighbours in the dark for the time being.

The policemen weren’t interested in explanations; they didn’t care what Max and I had been doing in the neighbour’s house, seemed completely unconcerned with what we had seen. That would come later, I guessed. They said no to a cup of tea, nodded politely to Millicent, who still hadn’t moved from her chair, and disappeared into our back garden. I went upstairs, and found Max in the bathroom, standing on the bath and looking out of the window as the policemen scaled the wall.

‘Bed, Max.’

‘OK, Dad.’

When he was tucked up, I drew up a chair beside the bed.

‘What are you doing, Dad?’

‘I thought I’d sit here while you go to sleep.’

‘I’m fine, Dad. Really.’

Three heavy knocks at the front door. A dream, perhaps?

2 (#ulink_126d08f5-0d40-565d-b111-b6139d4a6793)

Millicent’s side of the bed was empty. We had lain for hours without speaking, neither of us finding sleep. Then she had reached across for my hand, encircled my legs with hers, and held me very tightly. I had felt her breasts against my back, her pubic bone against the base of my spine, and I’d wondered why we rarely lay like this any more.

After some time, Millicent’s breathing had slowed and her grip loosened into a subtler embrace. I became more and more aware of her pubic bone, still gently pressing against me. But at the first stirring in my penis I remembered the neighbour’s half-erection in the bath. I stretched away from her, and she went back to her side of the bed.

‘Millicent?’

‘Mmm.’

‘Can we talk?’

‘Tomorrow,’ she had said.

Now I got up and dressed in yesterday’s clothes. I opened the door to Max’s room for long enough to see the calm rise and fall of his chest. Asleep. Clothes folded. Toys in their place. I watched him for a while, then went downstairs. Three minutes past six.

The cat tripped into the living room, tail high, limbs taut. She danced around my feet, and I reached down to her.

‘Hello, Foxxa.’ She sniffed approvingly at the tips of my fingers; then she pushed on to her hind legs, running her back upwards against the palm of my hand, forcing me to stroke her. For a moment she stood, unsteady, looking up, eyes bright and wide, as if surprised to find herself on two feet. Then she lowered herself on to all fours and wove a figure-of-eight around my calves, catlike again.

A mug on the living-room table: Millicent had drunk coffee in front of the television. I saw that the front door was unlocked, and found the kitchen empty. The cat followed me in, ate dried food from her bowl.

Millicent had left a folded note.

Alex,

We need to

talk Max (3)

talk school (1)

talk shrink (2)

talk police (?)

But please, none of this before we speak.

M

The coffee-maker was on the stove, still half-full. I checked the temperature with my hand. Warm enough to drink. I stood on the countertop and felt around on top of the cupboard, just below the plaster of the ceiling. Marlboro ten-pack. I took one and replaced the packet.

We had started hiding cigarettes from Max. He didn’t smoke them, as far as we could tell, but a pack left lying on the kitchen table would disappear. Millicent was certain that he sold them, but Max disapproved of our smoking with such puritanical disdain that I was sure he destroyed them.

In the garden I pulled the love seat away from the wall and drank my coffee, smoked my cigarette. On a morning like this, Crappy wasn’t so bad. No dogs barked, no one shouted in the street, no police helicopters watched from above. We should sort out the garden though. The garden was a state.

I stood on the love seat, looked back over the wall. Poor man, with his trimmed lawn, his verdant bower and his successful suicide attempt. From here there was nothing – nothing – that betrayed our neighbour’s sad, lonely death.

I pushed the love seat back against the wall and stood up, finished my cigarette, tried to plan the day. Quiet word with the teacher. Phone calls to the shrink. The police, I imagined, would make contact with us.

What had Max seen? When he had climbed the stairs behind me, what had he seen? That jolt, that first image, that’s what stays with you, isn’t it? Contorted face or pitiful erection? Rictus or dick? Which would be more traumatic for a boy of his age?

I flicked my cigarette butt over the wall and went back into the house. Max was in the kitchen, all pyjamas and tousled hair, rubbing sleep from his eyes. I bent down to hug him. He sniffed dramatically.

‘You’ve been smoking.’ But he threw his arms around my neck and hung there for a moment, then sat down at the table. I searched his face for some sign of something broken in him, but found nothing.

‘Max.’

‘Yeah.’

‘I’m going to be coming with you to school today. I need to tell your teacher what you saw.’

‘His name’s Mr Sharpe.’

‘… to tell Mr Sharpe what you saw.’

‘You forgot his name, didn’t you?’

‘Max. Can you listen?’

‘What? And why do you have to tell him?’

‘Because what you saw was very upsetting.’

‘It wasn’t.’

‘You might be upset later.’

He shrugged. ‘Can I be there when you tell him?’

‘Sure. OK. Why not.’

I kept expecting the police to knock on the door. Typical of Millicent to be out at a time like this.

I made a cooked breakfast to fill the time before we left. I let Max fry the eggs, which surprised him. It surprised me too. We ate in silence, then shared Millicent’s portion, enjoying our guilty intimacy. Max went upstairs. I put the plates and pans in the dishwasher and set it running. Millicent didn’t need to know.

Max came downstairs, dressed and ready to go. I texted Millicent to say I was taking him to school.

There was a man standing outside our house. He was casually dressed – leather jacket, distressed jeans – but there was nothing casual about his stance. Perhaps he had been about to knock, because the open door seemed to throw his balance slightly off. Max had flung it wide, and there stood the man in front of us, swaying, unsure of what to say.

‘Who are you?’ said Max. ‘Are you a policeman?’

The man nodded, ran the back of his hand across his mouth. He carried a briefcase that was far too smart for his clothes.

‘I could tell you were,’ said Max. ‘Are you going to arrest someone?’

The policeman ignored the question. ‘Mr Mercer?’ he said. I nodded, and he nodded at me again. He told me his name, and his rank. I immediately forgot both.

‘You got a minute?’

‘I was going to take Max to school.’

‘It’s OK,’ said Max. ‘I can just go.’

‘I’d like to speak to your son actually, if that’s all right. With your permission, and in your presence.’

No.

‘My name’s Max,’ said Max.

I looked at Max. You want to do this? He nodded at me.

‘OK,’ I said.

‘You’re giving your consent?’

‘I am,’ I said, ‘yes.’

‘Me too,’ said Max.

The policeman explained that this was not an interview, although he had recently been certified in interviewing children. He gave me a sheet of paper about what we could expect from the police and how to make a complaint if we were unhappy. Then he took out a notebook. I handed the paper to Max, who read it carefully.

First sign, I thought. First sign that this is taking a wrong turn and I end it and ask him to leave. He’s eleven.

I brought a chair in from the kitchen for the policeman. Max and I sat on the sofa. The policeman asked me where Millicent was, and I told him she was out. He asked me where she worked, and I said that she worked from home. He asked me where she was again. I said I wasn’t sure.

He made a note in his notebook.

‘She often goes out,’ said Max. ‘Dad never knows where she is.’

‘Max,’ I said.

‘Well, you don’t.’

The policeman made a note of this too.

‘Mum values her freedom.’

The policeman made yet another note. Then he took out a small pile of printed forms on to which he began to write.

‘How old are you, Max?’

‘Eleven.’

‘And is Max Mercer your full name?’

‘Yes. I don’t have a middle name.’

‘And you’re a boy, obviously.’

‘Obviously.’

They exchanged a smile; I realised that the policeman was simply nervous.

‘Can I sit beside you?’ said Max. ‘Just while you’re doing the form?’

The policeman looked at me.

‘If that’s OK with your dad.’

‘Sure,’ I said. I asked him if he wanted a coffee; he asked for a glass of water instead. I went through to the kitchen. Was he nervous, I wondered. Or are you playing nice cop?

‘I’m white British,’ I heard Max say, ‘even though British isn’t a race but the human race is. We’re not religious or anything. And my first language is English, so I don’t need an interpreter.’

He was reading from the form, I guessed, checking off the categories: so proud, so anxious to show how grown-up he could be. ‘For my orientation you can put straight.’

‘That’s really for older children,’ I heard the policeman say.

‘But can’t you just put straight?’

‘All right, Max. Straight.’

I came back in with the water. The policeman got up and sat opposite us again in the kitchen chair, writing careful notes as his telephone recorded Max’s words.

‘What were you doing before you found the neighbour, Max?’

‘Not much. Like reading and homework and stuff. I’m not allowed an Xbox or anything. And Mum was out, and Dad was working. He lets me borrow his phone, though.’

The policeman sent me an enquiring look. Then he made another note. I was wrong. It wasn’t nervousness; it was something else. There was a shrewdness to him that I hadn’t noticed at first, and that I didn’t much like. ‘We’re good parents,’ I wanted to say to him. ‘We love him unconditionally. We set boundaries.’ Don’t judge us.

He was good at speaking to children, though: I had to give him that. Max told him everything. That we had been looking for our cat, that the cat had led us into the neighbour’s house, that the back door had been open, and that the cat had disappeared up the stairs.

‘Is it better to say erection, or can I say boner?’ said Max.

‘Just say whichever you feel more comfortable saying,’ said the policeman.

‘But what should I say in court?’

‘I don’t think you’re going to have to speak in court,’ said the policeman. ‘That’s very unlikely.’

‘What would you say, though?’

The policeman laughed gently. ‘Probably erection. It’s the official word.’

‘OK.’ Max smiled a wide smile. ‘Erection.’ Then he became serious again; he made himself taller and stiffer, an adult in miniature. ‘Anyway, even though Dad tried to stop me seeing, I saw that the neighbour had an erection.’

I hadn’t tried to stop Max from seeing, though. At least I didn’t think I had. I was suddenly unsure. Perhaps I had.

‘I’m sorry, Max,’ said the policeman. ‘That must have been upsetting for you.’

‘You don’t mean the erection. You mean the dead body.’

‘Yes,’ said the policeman.

‘It was OK,’ said Max. ‘I mean, it wasn’t nice, but it was OK. Have you seen a dead body before?’

‘No,’ said the policeman, ‘only pictures.’

‘Isn’t it your job?’

‘We all have slightly different jobs,’ he said.

‘How long have you been a policeman?’

‘Couple of years,’ he said.

I had been wondering whether to send Max upstairs to his bedroom, or to ask whether I could drop Max at school and then come back. Of course, Max could have walked to school by himself, but I wanted to walk by my son’s side, to see him safely there, to make sure he was OK after the questions from the police.

The policeman didn’t need to speak to me. He had other children he had to speak to. Formal interviews.

‘Dark stuff,’ he said, and a troubled look clouded his features.

‘What dark stuff?’ said Max.

The policeman checked himself again. He stood up, put the forms in his briefcase, and handed me a card, told me his colleagues would be in touch to speak to me.

‘What dark stuff?’ said Max again.

‘Not all parents love their children the way your dad loves you, Max.’

As we left the house Max slipped his fingers through mine. Little Max, my only-begotten son. He hardly ever held my hand these days.

‘Dad,’ said Max, ‘Dad, Ravion Stamp had to go to the police station, and they filmed it and everything. And his dad wasn’t allowed to be there.’

‘That isn’t going to happen to you,’ I said.

‘But what if they arrest you?’

‘Why would they do that?’

‘But Ravion’s dad …’

Jason Stamp had violently assaulted his son. Ravion had testified by video link. I wasn’t sure how much Max knew about the case.

‘That won’t happen to us, Max. I promise you.’

‘But how could that man know that you love me?’ he said.

‘He could see it.’

‘How?’

‘OK, he was just guessing.’

‘You are so annoying, Dad,’ he said. But he leaned in to me and wrapped his arms around me for a moment. My beautiful, clever son. My only-begotten. Whose first word was cat and whose seventh was fuck; whose forty-fourth word was a close approximation of motherfucker.

Forget the swearing, though. We fed Max, we clothed him, we sang him to sleep at night. We set clear boundaries, and applied rules as fairly as we could. Our house was full of love. We are the classic good-enough parents.

Millicent and Max would bath together; I would hear their shrieks of laughter from halfway down the street. Listen to that: that’s the sound of my little tribe. Listen to that and tell me it’s not real.

Yes, we swore in front of Max, and yes, we smoked behind his back. That doesn’t matter. What matters is this – my wife, my son, the water and the laughter.

My little tribe.

Max let me hold his hand until we neared the school, then slipped his fingers from mine, walked beside me. On the final approach, he half-ran, putting ground between himself and me, anxious not to be seen arriving with a parent.

Millicent rang. I cradled the phone to my ear. Screams and shouts of morning break, six hundred London children giving voice.

‘I was worried.’

‘Hey. Sorry.’ Her voice was strained.

‘Where are you?’

‘On my way. You at the school?’

‘Yes.’

‘Wait for me?’

‘I’d hoped to speak to him before they go in again.’

‘You’ve forgotten his name again, haven’t you?’ Her voice softened.

‘I know. Bad Dad.’

‘So, you going to wait for me, Bad Dad?’

‘OK. All right.’

I saw Max in a dissolute huddle of boys, all oversized shirts and falling-down trousers. I caught his eye and pointed to the school building. ‘See you in there,’ I mouthed. He nodded and turned away.

Millicent arrived five minutes after the school bell. She was pale, the contours of her face shifted by lack of sleep. She reached up and kissed me.

Even in heels, Millicent was short. When we’d first met, it had made me want to protect her. Now I hardly noticed. I held her, grateful that she was there. She held me just as tightly. Then she ended the embrace by tapping me on the back.

‘Where’ve you been?’ I said.

‘Out. Thinking. Sorry.’

It’s been like this since we lost Sarah. Millicent’s reaction – her ultimate reaction, after she had fallen apart – was to do the opposite of falling apart. She reconstructed herself. She became supercompetent. Make your play, she writes, then move on. Play and move on.

The classroom looked like a post-war public information film, but with more black and brown faces. Didactic posters covered the walls. The children sat in orderly rows, working in twos from textbooks. Three rows back sat Max with his friend Tarek. He looked up when we entered, but didn’t acknowledge us.

Mr Sharpe too looked like a man from another age. Dark-skinned, and with close-cropped hair, dressed in a faultlessly pressed suit: like a black country schoolmaster from a time when no country schoolmaster was black. His hair was brilliantine slick, his moustache pencil thin, his hands delicate and agile.

‘May we speak with you?’ Millicent said. ‘We’re Max’s parents. We wanted to explain the reason for his lateness.’

‘Of course.’

‘In private.’ She turned towards the corridor.

‘Actually, that isn’t really appropriate.’ He gestured towards the class. I looked around, and found Tarek and Max looking directly at me. Tarek whispered something to Max; they looked at the teacher and at us, and laughed.

‘Unless, of course, you can wait until lunch break. Twelve fifteen. Here.’

‘We’d like Max to be present.’

Mr Sharpe nodded, waved us from the room and closed the door behind us.

3 (#ulink_f729b8e7-a2fd-556e-a12c-8f29616e7ce7)

‘Uh huh,’ said Millicent. ‘That sure went well.’

We bought bad coffee from a bad café, drank it from bad Styrofoam cups on a low wall on the baddest of Crappy’s bad streets. I lit a cigarette, and we shared it like the bad boy and bad girl we weren’t and never would be.

Millicent inhaled deeply, holding back some of the smoke inside her mouth, catching it as it started to wisp upwards, then sucking it hungrily down into her primed lungs. Two hits in one draw: proper film noir smoking. Even after thirteen years of marriage it suggested something unknowable, some glamorous secret that I was never quite party to.

‘What is it, Alex?’

‘You. Smoking in the sun. Hello.’

That same image – Millicent, backlight and smoke. It repeats itself sometimes, and it catches me off guard. It’s no more than a sliver of who she is, a reminder of a moment before we began to share our imperfections with each other. The American girl I met in the pub.

‘So,’ said Millicent, ‘the radio thing.’

‘I’m sorry. I should have listened to it.’

‘No, I kind of get why you couldn’t do that, Alex.’ She laughed gently. ‘I really did not see that one coming.’

I laughed too, then stopped, brought up short by the flash frame of the neighbour that cut hard into my thoughts: the broken body in its broken bathtub, the blooded eye cold against the London heat. Water falling through space.

Three frames of the wrong kind of reality.

‘What is it, Alex, honey?’

Erase. Breathe.

‘Alex, are you OK?’

‘Yes,’ I said. Breathe.

Millicent looked concerned, put a hand on my arm.

‘I’m fine.’ I breathed.

‘You’re fine?’

‘I’m fine.’ I breathed again. ‘You said you didn’t suck, Millicent.’

‘No, I sucked a little, but I didn’t stink.’

‘They gave you flowers.’

‘It was an evening transmission. I guess they already bought them before the show.’

‘But they liked you. Come on.’

‘Yes.’ Her eyes shone. ‘Yes, I guess they did like me. Because also they gave me this. Look.’ From her bag she produced an envelope.

I took it from her.

‘Wow,’ I said. ‘A contract.’

‘A letter of engagement. They emailed it to me. At four thirty this morning.’

‘You can’t have sucked at all, Millicent.’

‘They’re on summer schedule. They need cover. Tuesdays eight to ten. Four weeks.’

‘Wow,’ I said again.

‘Yeah, wow,’ she said. ‘That’s good, right?’

‘It’s brilliant, and you know it.’

My America.

We sat grinning at each other on our low wall.

Manifest destiny.

The meeting with Mr Sharpe lasted ten minutes. Max spent the first five looking out of the classroom window. When I described my fear that what he had seen might have traumatised him, must have traumatised him, Max looked round at me, then at Mr Sharpe. Then he yawned and went back to looking out of the window.

Mr Sharpe listened closely. When I had nothing more to say, he sat, drumming his fingers lightly on his desk, looking from Millicent to me, and back again. He opened a notebook that had been lying on the desk.

‘So, Mrs … I’m sorry, Ms Weitzman.’

‘Millicent.’

‘Hmm. Quite so. You asked that Max be present at this meeting. May I ask why?’

‘You wanted to be here,’ I said, ‘didn’t you, Max-Man?’

‘Yes,’ said Max, still looking out of the window.

‘And why was that, Max?’ asked Mr Sharpe, closing his notebook and placing it carefully back on the desk.

‘I don’t know, Mr Sharpe.’

‘Do you have anything to add to what your father has told me?’

‘No, Mr Sharpe.’

‘All right, Max. Run along and join your friends, then.’

Max left the room, closing the classroom door with exaggerated care. Millicent and I exchanged a look. Run along? Still, there was something strangely comforting about this odd little man with his easy paternalism and his brilliantined hair.

Through the wired glass I saw Max linger for a moment, then he disappeared down the corridor.

‘So, Millicent and …’

‘Alex.’

‘Millicent and Alex. Quite. Max seems well-adjusted, well-parented, if I may use that expression. You may be sure that I shall keep an eye open for any sign of the trauma that concerns you.’

‘That’s most kind of you, Mr Sharpe,’ said Millicent.

‘Yes, thank you,’ I found myself saying. ‘Really very kind indeed.’ The man’s formality was catching.

Mr Sharpe smiled a benign smile. ‘Of course, it’s summer break soon, and Max will be leaving us in a few short weeks. Was there anything else?’

‘Not unless there’s anything you would like us to address at home,’ I said, surprised that he hadn’t mentioned Max’s swearing.

‘No, as I said, a well-brought-up boy. Nice circle of friends, never in trouble. Studious, but not a prig. Neither a victim nor a bully. He listens in class, he does his homework, he reads well. He will settle well into secondary school life; I have no doubt of it. I’m not really sure what more I can say.’

‘Well parented, you said?’ asked Millicent.

‘Yes, a credit to you and your husband.’

‘He doesn’t seem in any way odd to you?’

‘Dear me, no. Why?’

We didn’t see Max as we left the school.

‘Shouldn’t that man be a country schoolmaster somewhere in the middle of the 1950s?’ I said.

‘I kind of liked him,’ said Millicent.

‘Me too. Strange that Max likes him so much, though.’

‘Kids don’t like teachers who want to hang out; they don’t like for adults to talk about hip hop and social networking. They want to know where the line is, and what will happen when they cross that line. Especially boys. They’re kind of hardwired conservative at that age.’

‘But how does that work here in Crappy?’

‘So many questions, Alex. Aren’t you tired?’

Seventy hours of footage sitting on my computer. Five days to view it.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/ben-mcpherson/a-line-of-blood/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Ben McPherson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Триллеры

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A chilling psychological thriller about family – the ties that bind us, and the lies that destroy us. Perfect for fans of The Girl on the Train and I Let You Go.You find your neighbour dead in his bath.Your son is with you. He sees everything.You discover your wife has been in the man’s house.It seems she knew him.Now the police need to speak to you.One night turns Alex Mercer’s life upside down. He loves his family and he wants to protect them, but there is too much he doesn’t know.He doesn’t know how the cracks in his and Millicent’s marriage have affected their son, Max. Or how Millicent’s bracelet came to be under the neighbour’s bed. He doesn’t know how to be a father to Max when his own world is shattering into pieces.Then the murder investigation begins…