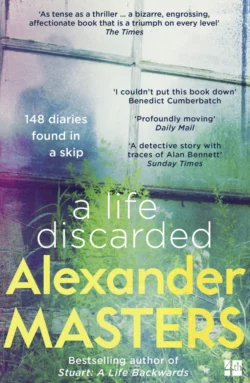

A Life Discarded: 148 Diaries Found in a Skip

Alexander Masters

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 621.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Unique, transgressive and as funny as its subject, A Life Discarded has all the suspense of a murder mystery. Written with his characteristic warmth, respect and humour, Masters asks you to join him in celebrating an unknown and important life left on the scrap heap.A Life Discarded is a biographical detective story. In 2001, 148 tattered and mould-covered notebooks were discovered lying among broken bricks in a skip on a building site in Cambridge. Tens of thousands of pages were filled to the edges with urgent handwriting. They were a small part of an intimate, anonymous diary, starting in 1952 and ending half a century later, a few weeks before the books were thrown out. Over five years, the award-winning biographer Alexander Masters uncovers the identity and real history of their author, with an astounding final revelation.A Life Discarded is a true, shocking, poignant, often hilarious story of an ordinary life. The author of the diaries, known only as ‘I’, is the tragicomic patron saint of everyone who feels their life should have been more successful. Part thrilling detective story, part love story, part social history, A Life Discarded is also an account of two writers’ obsessions: of ‘I’s need to record every second of life and of Masters’ pursuit of this mysterious yet universal diarist.