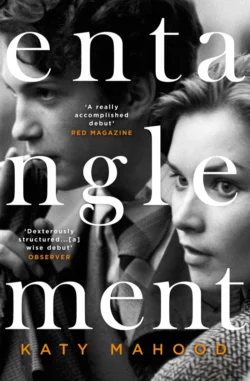

Entanglement

Katy Mahood

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 774.62 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Dexterously structured … [a] wise debut’ Observer‘A hugely impressive debut’ Stella Duffy‘Beautifully written’ Hannah Beckerman‘A really accomplished debut’ Red MagazineOn a hot October day in a London park, Stella sits in her red wedding dress opposite John. Pregnant and lost in thoughts of the future, she has no idea that lying in the grass, a stone’s throw away, is a man called Charlie. From this moment, Stella and Charlie’s lives are bound together in ways they could never imagine. But all they have is a shared glance and a feeling: have we met before?Entanglement is a bewitching novel of love and sacrifice which explore show our choices can reverberate across the generations, and the sparks of hope they can ignite.