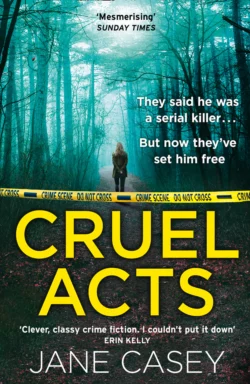

Cruel Acts

Jane Casey

From award-winning author Jane Casey comes another powerful Maeve Kerrigan crime thriller which will keep you on the edge of your seat until the final page!How can you spot a murderer? Leo Stone is a ruthless killer – or the victim of a miscarriage of justice. A year ago, he was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. But now he’s free, and according to him, he's innocent. DS Maeve Kerrigan and DI Josh Derwent are determined to put Stone back behind bars where he belongs, but the more Maeve finds out, the less convinced she is of his guilt. Then another woman disappears in similar circumstances. Is there a copycat killer, or have they been wrong about Stone from the start?

Copyright (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Jane Casey 2019

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (forest and yellow tape)

Jane Casey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008149031

Ebook Edition © April 2019 ISBN: 9780008149055

Version: 2019-02-13

Dedication (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

For Sinéad and Liz, my wise women

Epigraph (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

The investigator should pursue all reasonable lines of enquiry, whether these point towards or away from the suspect.

Code of Practice for Investigators

Contents

Cover (#u362e4aac-1b60-54ab-9590-13215aa5920a)

Title Page (#u7f0026c8-9ce9-53b2-808f-3d4c0b548235)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Jane Casey

About the Publisher

1 (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

The house was dark. PC Sandra West stared up at it and sighed. The neighbours had called the police – she checked her watch – getting on for an hour earlier, to complain about the noise. What noise, the operator asked.

Screaming.

An argument?

More than likely. It’s not fair, the neighbour had said. Not at two in the morning. But what would you expect from people like that?

People like what?

A check on the address had told Sandra exactly what kind of people they were: argumentative drunks. She’d never been there before but other officers had, often, trying to persuade one or other of them to leave the house, to leave each other alone, for everyone’s sake. It was depressing how often she encountered couples who had no business being together but who insisted, through screaming rows and bruises and broken teeth, that they loved each other. Sandra was forty-six, single and likely to remain so, given her job (which was a passion-killer, never mind what they said about uniforms) and her looks (nothing special, her father had told her once). Generally, she didn’t mind. It was peaceful being on her own. She could do what she wanted, when she wanted.

Sandra had a look in the boot of the police car and found a stab vest. Slowly, fumbling, she hauled it around her and did it up. It was stiff and awkward, made to fit someone much taller than Sandra. Still, it was in the car for a reason. She walked up the path to the front door. Everything was quiet. Hushed.

Maybe one of them had taken the hint and left before the busies arrived. Sandra shone her torch over the window at the unhelpful curtains, then bent and looked through the letterbox. A dark hallway stretched back to the kitchen door. It was quiet and still.

A screaming argument that ended with everyone tucked up in bed an hour later? Not in Sandra’s experience. She planted her feet wide apart, knowing that she had enough bulk in her stab vest and overcoat to intimidate anyone who might need it. Then she rapped on the door with the end of her torch.

‘Police. Can you open the door, please?’

Silence.

She knocked again, louder, and checked her watch. God, nights were hard work. It was the boredom that wore you down, that and the creeping exhaustion that was difficult to ignore when you weren’t busy. She wasn’t usually single-crewed but some of her rota were off sick. She never got sick. It was something she took for granted – the colds and viruses and stomach bugs all passed her by. It made her wonder if everyone else was really sick or if they were faking, and whether she was stupid not to do the same. She tried to suppress a yawn with an effort that made her jaw creak. It was tempting to call it in as an LOB. Sandra smiled to herself. It wasn’t what they taught you at Hendon, but every police officer knew what it stood for: Load of Bollocks. Then she could get back into the car and go in search of refs. She hadn’t eaten for hours, her stomach hollow from it. Knowing her luck, she’d be about to bite into what passed for dinner and her radio would come to life.

The trouble was, there was a kid in the house. You couldn’t just walk away without finding out if the kid was safe. Not when there was a history of domestic violence and social services being involved. Chaotic was the word for it: not enough food in the house, patchy attendance at school, the boy needing clean clothes and haircuts and a good bath. How could you have a kid and not take responsibility for him? OK, Sandra’s parents had been short on hugs and they hadn’t had a lot of money to spend on her and her brothers, but they’d been reliable and she’d never once gone hungry. Nothing to complain about, even if she had complained at the time.

She bent down again and peered through the letterbox, moving the torch slowly across the narrow field of view this time. It cast stark shadows in the kitchen and across the stairs. But there was something … she squinted and changed the angle of the torch, trying to see. There, on the bottom step: light on metal. And again, two steps up. And again, three steps above that.

Knives. Kitchen knives.

They were stuck into the wood of the stairs, point first. All the way up, into the darkness at the top.

Sandra wasn’t an imaginative person but she had an overwhelming sense of fear all of a sudden, and she wasn’t sure if it was her own or someone else’s.

‘Hello? Can you hear me? Open the door, please, love. I need to check you’re all right.’

Silence.

Oh shit, Sandra thought, but not for her own sake, despite being scared at the thought of what might confront her inside the house. Oh shit something very bad has happened here. Oh shit we probably can’t make this one right. Oh shit we should have come out a lot sooner.

Oh shit.

She got on her radio and asked for back-up.

‘With you in two minutes,’ the dispatcher said, and Sandra thought about two minutes and how long that might be if you were scared, if you were dying. She’d asked for paramedics too, hoping they’d be needed.

The second police car came with two large constables, one of whom put the door in for her. His colleague went past him at speed, checking the rooms on the ground floor.

‘Clear.’

Sandra was halfway up the stairs, listening to her heart and every creak from the bare boards. The torch was slick in her hand.

‘Hello? Anyone here?’

The thunder of police boots on the steps behind her drowned out any sounds she might have heard. Bathroom: filthy in the jumping light from her torch, but no one hiding. A bedroom, piled high with rubbish and dirty clothes. No bed, but there was a pile of blankets on the floor, like a nest. A second bedroom was at the front of the house. It was marginally tidier than the other one, mainly because there was almost no furniture in it apart from a mattress on the floor. Shoes were lined up neatly in one corner and a collection of toiletries stood in another.

The woman was lying across the mattress, half hanging off the edge, a filthy blanket draped across her. Her head was thrown back. Dead, Sandra thought hopelessly, and made herself smile at the small boy who crouched beside the body.

‘Hello, you. We’re the police. Are you all right?’

He was small and dark, his hair hanging over his eyes. He blinked in the light, his eyes darting from her to the officer behind her. He wasn’t crying, and that was somehow worse than if he’d been sobbing. Sandra was bad at guessing children’s ages but she thought he could be eight or nine.

‘What’s your name?’

Instead of answering he huddled closer to the woman. He had pulled one bruised arm so it went around him. It reminded Sandra of an orphaned monkey clinging to a cuddly toy.

‘Can I come a bit closer? I need to check if this lady is all right.’

No reaction. He was staring past her at the officer behind her. She waved a hand behind her back. Give me some room.

‘Is this your mummy?’ she whispered.

A nod.

‘Is your daddy here?’

He mouthed a word. No. That was good news, Sandra thought.

‘Was he here earlier?’

Another nod.

Sandra inched forward. ‘Did you put that blanket over your mummy?’

‘Keep her warm.’ His voice was hoarse.

‘Good lad. Good idea. And you put something under her head.’

‘Coat.’

‘Brilliant. Can I just check to see if she’s all right?’ Sandra stretched out a gloved hand and touched the woman’s ankle. Her skin was blue in the light of the torch, and even through the latex her skin felt cold.

‘He hurt her.’

‘Who did, darling? Your dad?’

The boy blinked at her. After a long moment, he shook his head slowly, definitely. It would be someone else’s job to find out who had done it, Sandra thought, and was glad it wasn’t her responsibility. The closer she got to the woman on the mattress, the more she could see the damage he’d done to her. And the boy had watched the whole thing, she thought.

‘All right. We’ll help her, shall we?’

His huge, serious eyes were fixed on Sandra’s. She wasn’t usually sentimental, but a sob swelled up from deep in her chest and burst out of her mouth before she could stop it. She held out her arms. ‘Come here, little one.’

He shrank into himself, turning away from her towards his mother. Too much, too soon. She bit her lip. The sound of low voices came from the hall: the paramedics at long last.

‘I’m sorry, but you can’t stay here. We’ve got an ambulance for your mummy. We need to let the ambulance men look after her.’

‘I want to stay. I want to help.’

‘But you can’t.’

The boy gave a long, hostile hiss, a sound that made Sandra catch her breath. The paramedics crashed into the room, carrying their equipment, and shoved her out of the way. She leaned against the wall as they bent over the figure on the mattress. It was as if Sandra had come down with a sudden, terrible illness: her stomach churned and there was a foul taste in her mouth. A cramp caught at her guts but she couldn’t go, not in the filthy bathroom, not in what was going to be a crime scene. She clenched her teeth and prayed, and eventually the pain slackened. A greasy film of sweat coated her limbs. She lifted a hand to her head and let it fall again. What was wrong with her?

The boy had scrambled back when the paramedics crashed into the room. He crouched in the corner of the room among the shoes, those round solemn eyes taking everything in. Sandra watched him watching the men work on his mother’s body, and she shivered without knowing why.

2 (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

It was a day like any other; it was a day like they all were inside. Time pulled that trick of dragging and passing too quickly and all that happened was that he was a day further into forever.

He sat on his own, in silence, because he’d been allocated a cell to himself. It was for his protection and because no one wanted to share with him. He wasn’t the only murderer on the wing – far from it – but he was notorious, all the same.

That wasn’t why no one wanted to share with him. His health wasn’t good, a cough rattling in his chest all night long. That was more of a problem than the killing, he thought. But he’d taken his share of abuse for the murders, all the same. No one liked his kind.

He shifted his weight in the cheap wooden-framed armchair, feeling it creak under him. He had never been a fat man but prison had pared away at his flesh, carving out the shadow of his bones on his face.

The room was fitted out like a cheap hostel – a rickety wardrobe, a small single bed, a desk against the wall. There were limp, yellow curtains at the window. At a glance you might not notice the bars across the same window, or the stainless steel sink, or the toilet that was behind a low partition. That was one good thing about being on his own. He’d shared cells before, when he was younger. You never got used to the smell of another man’s shit. Of all the smells in the prison – and there were many – that was the worst.

He picked up the envelope that he’d left lying on his desk. It was open. A screw would have read it before he ever saw it. That was standard. Small writing, black ink. He wasn’t used to seeing it: his name in that writing. He turned it over a couple of times. Nothing important in it or he’d never have seen it. But no one writes a letter without saying something, even if they don’t mean to say anything at all.

He ripped the envelope getting the letter out of it. The paper was flimsy, the words on the other side bleeding through. He wasn’t a great reader at the best of times. His eyes tracked down the centre of the page, the scrawl transforming itself into phrases here and there. Don’t forget we’re all trying … I know you can … easy for me to say … coming to see you … your appeal … lose heart … forget what happened … start again … have hope … your son.

‘Fuck you.’ It was a whisper, inaudible above the banging and shouting and echoing madness of a prison in the daytime. With a wince, he got to his feet and crossed to the toilet. He stood over it, tearing the letter in half and half again, ripping the paper until it was a handful of confetti. He dropped it into the bowl. He’d imagined the ink would run but it didn’t. The paper sat on the surface of the water, the black writing burning itself onto his retinas. He pissed on it in a stop-start trickling stream, annoyed by that as much as the way the paper stuck damply to the sides of the toilet. He flushed, and waited, and grimaced at the scattered, dancing fragments that remained in the water.

He had a whole life sentence stretching ahead of him but that wasn’t what made him bitter.

If by some miracle he got out, he would never be free.

3 (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

The lift doors closed and I shut my eyes, then forced them open again. It took about half a minute to go from the ground floor to our office: thirty seconds wasn’t quite long enough for a cat nap, even for me. The weight of the box I was carrying pulled at the muscles in my shoulders and arms but that was fine; it distracted me from the wholly unpleasant sensation of mud-soaked boots and trouser legs. I didn’t need to glance in the lift’s mirror to see how bedraggled I was after a long night and a cold morning at a crime scene in a bleak, muddy yard. I only had to look to my left, where Detective Constable Georgia Shaw was hunched inside a coat that was as saturated as mine. Her usually immaculate fair hair hung around her face in tails. Like me, she was holding a heavy cardboard box filled with evidence bags and notes.

‘We drop this stuff off. We do our paperwork.’ I paused to cough: the chill of the night had sunk into my chest. ‘We finish up and we go home.’

Georgia nodded, not looking at me.

‘Nothing else. Home, hot baths, clean clothes, get some sleep.’

Another nod.

‘If anyone manages to track down Mick Forbes and he gets arrested we’ll have to come back to interview him.’ Mick Forbes, a scaffolder in his fifties, the chief and only suspect in the murder of his best friend, Sammy Clarke, who had been battered to death in the muddy yard where we’d spent the night.

Georgia sniffed.

‘So get some rest while you can.’

‘OK.’ Her voice was a whisper.

The lift doors opened and I strode out, trying to look as if it was normal for my feet to squelch as I walked through the double-doors into the office. Head high, Maeve.

A quick scan of the room was reassuring: a handful of colleagues, mostly concentrating on their work or on the phone. A few raised eyebrows greeted me. An actual laugh came from Liv Bowen, my best friend on the murder investigation team, who bit her lip and dragged her face into a serious expression when I glowered at her. But for a brief moment, I allowed myself to feel relieved. I’d got away with it this time. I’d rush through the paperwork and then escape, unseen by—

DCI Una Burt opened the door of her office. ‘Maeve? In here. Now.’

I stopped, caught in the no man’s land between her door and my desk. Common sense dictated I should put the box down rather than carrying it into her office, but that meant leaving my evidence unattended. ‘Ma’am, I’ll be with you in a minute—’

‘Right now.’ The edge in her voice was serrated with irritation and something more unsettling. The box could come with me, I decided, and trudged through the desks to Burt’s office.

My first impression was that it was full of people. My second was that I would rather have been just about anywhere else at that moment, for a number of reasons. The pathologist Dr Early sat in a chair by the desk, tapping her fingers on a cardboard folder that was on her knee. She was young and thin and intense, rarely smiling – which I suppose wasn’t all that surprising, given her job. Today she looked grimmer than usual. Standing beside her, to my complete surprise, was a man who was tall, silver-haired and catch-your-breath handsome. My actual boss, although he was currently supposed to be on leave: Superintendent Charles Godley.

‘Sir.’

‘Maeve.’ He smiled at me with genuine warmth as I put the box down at my feet. ‘You look as if you had an interesting night.’

‘Not the first time she’s heard that. But I’ll give you this, Kerrigan, you don’t usually look as if you spent the night in a sewer.’ The inevitable drawl came from the windowsill where a dark-suited man lounged, his arms folded, his legs stretched out in front of him so they took up most of the room. Detective Inspector Josh Derwent, the very person I had been hoping to avoid. I could feel his eyes on me but I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of reacting. Instead I smiled back at Godley.

‘It wasn’t the most pleasant crime scene, but I’ll live. It’s good to see you, sir.’

‘You too.’

‘Are you coming back to us?’ I had sounded over-enthusiastic, I thought, and felt the heat rising to my face. Una Burt wouldn’t like it if I was too keen to see Godley return. She had only been a caretaker, though, standing in for him while he was away on leave.

‘Not quite. Not yet.’ The smile faded from his face. ‘I’m here for another reason. I’ve got a job for you.’

‘For me?’

‘For you and Josh.’ Una bustled around to sit behind her desk, pausing until Derwent moved his feet out of her way. She sat down, pulling her chair in and leaning her elbows on the desk – the desk she had inherited from Godley. He was much too polite to react, although I knew he would have recognised it as her marking her territory. Currently, he was a visitor in her office and she wanted him to know it.

‘What sort of job?’ I asked, wary.

‘Leo Stone,’ Godley said. ‘Our latest miscarriage of justice.’

I frowned, trying to place the name. ‘I don’t think I know—’

‘Yeah, you do.’ Derwent’s voice was soft. ‘The White Knight.’

That sounded more familiar to me. Before I’d run the reference to earth, though, Godley snapped, ‘I don’t like that name. I don’t like glamorising murder. We’re not tabloid journalists so there’s no need to use their language.’

Derwent shrugged, not noticeably abashed. Before he could say something unforgivable and career-threatening, I spoke up.

‘You said a miscarriage of justice.’ I didn’t know why I was distracting Godley from Derwent. If the situation were reversed he would sit back and enjoy my discomfort. ‘What’s happened?’

‘He was convicted last year, in October. He’s been in prison for thirteen months now. One of the jurors in his trial has spent that time writing a book about the experience, and self-published it without running it past a lawyer. In it, he happens to mention how he and another juror looked up Stone on the internet, against the judge’s specific instructions, during the trial.’ Anger made Godley’s voice clipped, the words snapped off at the end. ‘They discovered Stone’s previous convictions for violence and told all the other jurors about it.’

‘I think my favourite line is, “We left the court to discuss the evidence we’d heard, but it was just a pretence. We had already decided he was guilty, because of what we’d found out for ourselves.”’ Burt leaned back in her chair. ‘Exactly what you don’t want a jury to say. But instead of making his fortune selling his book, he’s earned himself a two-month sentence for contempt of court.’

‘So Stone’s appealing.’ It wasn’t a question: there wasn’t a defence lawyer in the world who would let an opportunity like that slip through their fingers.

‘He is. At the end of this week. And the appeal will be granted,’ Godley said.

‘Right.’ Lack of sleep was making my head feel woolly. ‘Well, there’ll be a retrial. The problem was with the jury, not the evidence.’

‘There should be a retrial. But that’s the issue I have.’ Godley looked at me, his eyes even bluer than I’d remembered. ‘What do you know about the case?’

‘A little. Not much more than I read in the papers.’ I tried to remember the details I’d gleaned. ‘They called him the White Knight because he seemed to be rescuing his victims. He kidnapped them and killed them, either immediately or later. By the time we found the bodies they were too decomposed to tell us much about what he’d done.’

He nodded. ‘We only found two bodies but we’re fairly sure there’s at least one more victim. I wouldn’t be surprised if there were more out there. He was a nasty piece of work. He was abusive in his relationships, he had convictions for fraud, burglary and theft, and he had a lengthy history of violence towards strangers, as the jury found out.’

‘When is he supposed to have started killing?’ I asked.

‘He got out of prison three years ago after serving five years for burglary. The first murder was a month later – a woman named Sara Grey. It was opportunist. Impulsive. I don’t believe he planned it particularly well but it worked so he tried it again.’ Godley folded his arms. ‘Don’t be misled by the nickname. He was a murderer, plain and simple, but they had to try and make him into something more exciting. They twisted the facts because they wanted to sell newspapers, not because it was true. He saw his opportunity to kidnap women and he took advantage of that. Three women disappeared in similar circumstances, but he was only charged with killing Sara Grey and Willa Howard. And he was convicted.’

‘OK.’ I was trying to read Godley’s expression. ‘But why does that involve us? It was Paul Whitlock’s team who investigated the killings, wasn’t it?’

‘It was, and he did a good job. But Glen Hanshaw was the pathologist who did the post-mortems.’

‘Oh.’ I didn’t need to say any more. I understood the problem now. Glen Hanshaw had been a good friend of Godley’s. He had clung on to his job despite the ravages of cancer, right up to the end. I was starting to see why Godley was so upset.

‘There have been two acquittals in murder trials since he died, largely because he wasn’t there to defend his findings.’

‘And because his findings were shaky,’ Dr Early said. She glanced up at Godley, her face set. ‘He was a fine pathologist but he started making mistakes in the months before he died and he wouldn’t accept that his judgement was impaired.’

‘The pain medication affected him,’ Godley said. ‘He wanted to work – it was the only thing that mattered to him. But he needed to be dosed up to be able to do the job.’

‘He should have known better than to persevere. It was self-indulgent.’ It was professionalism that made Dr Early sound so severe. I knew she had done her utmost to help and support Dr Hanshaw, and that she had mourned him as a mentor, if not a friend. Glen Hanshaw had been a short-tempered misogynist and I’d never really understood Godley’s fondness for him.

Now the superintendent sighed. ‘Whether he should have been working or not, he’s become a target for defence lawyers. If he was involved in a case, you can expect the evidence he gathered to be challenged. And in the case of Leo Stone, the defence team are going to be looking for anything they can throw at the new jury to distract them from Stone’s guilt.’

‘The trouble with retrials,’ Derwent said, ‘is that they’ve heard all the best lines already. If you go back with exactly the same case and run it the same way, the defence know what to expect.’

‘Which is where you come in,’ Godley said. ‘I want to put a stop to the attacks on Glen’s reputation and his work. Dr Early has agreed to review his cases going back to before his diagnosis, and specifically his work on Leo Stone’s prosecution. In the meantime, I don’t want any cases to collapse purely because of his involvement. His reputation matters, and not just because he’s not here to defend himself. If all his decision-making is called into question we are going to see a torrent of appeals, especially from prisoners with whole-life tariffs.’

‘The worst of the worst,’ Una Burt said. ‘And they have nothing better to do than look for grounds to appeal. They’re in for life; they don’t have anything to lose.’

Godley turned to me. ‘Maeve, I want you and Josh to look at the case against Stone. Start from scratch: witnesses, families, the works. I’ll arrange a meeting with Paul Whitlock.’

‘He’s going to be pleased,’ Derwent observed. ‘Nothing like having another team come and take over your case.’

‘He’ll be professional about it,’ Godley said sharply. ‘He’ll understand why I don’t want to take any chances. Whitlock’s priority, and mine, is making sure that the right man is in prison for the murders of Sara Grey and Willa Howard. If that man is Leo Stone, I want him off the streets and behind bars.’

‘So don’t wind them up, Josh.’ Una Burt leaned all the way back in her chair, acting casual although her eyes were bright.

Derwent looked hurt. ‘Why single me out?’

‘Because I trust Maeve to behave herself.’ And I don’t trust you. She didn’t need to say it out loud. I suppressed a wince. Burt didn’t like Derwent, but I was the one who’d suffer for it.

‘Josh, I want you working on this case because I know you’ll do a good job. But Una is right. This is a high-profile investigation and you will be under scrutiny. It’s worth bearing that in mind from the start.’ There it was: the smooth diplomacy I’d missed so much from Godley. Derwent subsided, placated, and yet, from the satisfied expression on her face, Una Burt seemed to feel as if she’d won too. I had missed Godley more than I realised.

‘Can Georgia finish up on your case from last night?’ Burt asked me.

‘She should be able to handle it. We don’t have anyone in custody yet.’

‘I’ll get someone to take over as OIC.’ Burt squinted through the window that gave her a view of the office. ‘Chris Pettifer doesn’t look too busy.’

I didn’t want her to get someone else to take over – it was my case after all – but I knew that it was pointless to protest when DCI Burt had made up her mind. I made my face blank and nodded when Burt told me to brief Pettifer on the case before I went home.

‘You can take the files on the Stone case. Get your head around it before tomorrow.’

Or I could sleep, I thought, since I hadn’t for twenty-four hours. I could have a long bath and a decent meal and sleep.

‘Fine,’ I said.

Derwent stood up and stretched. ‘That’s useful. You do the reading, Kerrigan, and you can give me the highlights tomorrow.’

‘Why can’t you read up on it yourself?’ The question slipped out before I thought about whether it was appropriate for me, a detective sergeant, to ask a detective inspector why he wasn’t doing his job.

‘I’m busy,’ Derwent said coldly.

‘Right,’ I said under my breath, and bent down to pick up the box at my feet. Godley opened the door for me. Because I was tired and not really paying attention I started to move towards it at the precise moment when Derwent was walking past, and collided with him. I stepped back, horrified. He looked down at his shirtfront where a long black streak of mud had suddenly appeared on the immaculate white cotton.

‘Kerrigan.’

‘It was an accident,’ I said quickly.

He gave me the kind of look that he usually reserved for child-killers at the very least, and for a beat I held my breath. Then he lifted the box out of my hands as if it weighed nothing and walked away.

‘I can manage,’ I said to his retreating back, futilely.

‘Thank you, Maeve,’ Una Burt said from behind her desk, and I remembered where I was, and left her to her discussions with Godley and the pathologist.

4 (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

Derwent was always a fast mover. By the time I made it out of Una Burt’s office, he was already on the other side of the room, well out of reach. He set the box down beside Pettifer’s desk with a remark that made the big DS throw his head back and laugh. I started towards them – it was still my case to hand over, I thought with a shiver of irritation – and checked myself as Georgia stepped into my path. She had found a hairbrush and cleaned herself up a bit. She’d managed to find the time to reapply her mascara, I noted.

‘What was that about?’ She nodded towards the office behind me. ‘Is that Superintendent Godley?’

‘Yeah.’ Of course Georgia would have spotted him. She had an extraordinary instinct for career advancement.

‘What’s he doing here?’

‘He had a job for me.’

‘Can I help?’

I raised my eyebrows. ‘You don’t even know what it is.’

‘So?’ Georgia’s blue eyes were unblinking. I could see it from her point of view: a chance to impress the boss before he came back to the team. Get a head start. Make progress.

‘I’m not in charge of this one.’

‘Who is? DI Derwent?’ She swung round, looking for him.

‘You’re going to be working with Pettifer on the Clarke case,’ I said firmly. ‘Once that’s out of the way, we might be able to use you. But at the moment—’

She pulled a face, obviously annoyed. ‘Pettifer can finish the Clarke case on his own.’

‘He could, but he isn’t going to.’ I stared her down for a long moment, daring her to take it further, and in the end she broke first.

‘So what’s the case?’

‘Reinvestigating—’ I broke off to cough. ‘Reinvestigating the Leo Stone case.’

‘The White Knight? Wow. I would love to work on that.’

‘Noted.’ There was nothing to encourage her in my tone of voice.

‘Why did Superintendent Godley want you to work on it?’ Her eyes were narrow.

Derwent leaned in between us. ‘Because he has a soft spot for Kerrigan.’ Georgia laughed.

‘Because he thinks I’ll do a good job,’ I said stiffly.

‘Of course you will.’ Derwent patted my arm.

Instead of arguing the point I walked away from both of them to talk to Pettifer myself. Georgia could try to convince Derwent to let her work on it too. If he wanted her, he’d include her in spite of my objections. If he didn’t want her help, nothing I could say would persuade him. Either way, I didn’t need to hang around.

He caught up with me in the kitchen where I was waiting for the kettle to boil.

‘What’s up with you?’

‘Nothing.’ I coughed again. Shit, I didn’t want to be ill. ‘I’m tired. I’m cold. I want to go home.’

‘My home.’

‘I’m renting it. That means it’s my home. Temporarily, anyway.’ I still wasn’t used to living in a space that I associated so completely with Derwent. For instance, I’d discovered there was no bleach strong enough to take away the mental image of him lounging in the bath.

‘As long as you’re looking after it.’

‘Yeah, I don’t want to piss off the landlord.’

‘Oh, you’ve done that already. Look at me.’

I did, reluctantly. He was holding the sides of his jacket open so I could see the muddy mark that ran across his chest. Not just the shirt: the tie too. ‘I said I was sorry.’

‘No, you said it was an accident.’

‘Well, it was.’ I took a deep breath. ‘But I’m sorry.’

‘Finally. You’re forgetting your manners.’

‘Speaking of which, I could manage the box by myself. You didn’t even ask before you took it.’

His eyebrows went up. ‘Don’t try to pretend that’s why you’re in a mood.’

‘I’m not in a mood.’ I turned and leaned against the kitchen counter, gripping it for courage. ‘I am very annoyed that you decided to stir up trouble by hinting that Godley wanted me to work on this case for any other reason than that he thinks I’m a good detective. You of all people know how unfair it is to suggest he puts professional opportunities my way for personal reasons.’

Derwent gave me his stoniest look. ‘That’s not what I did.’

‘Isn’t it?’

‘No.’

‘Saying he had a soft spot for me?’

‘It’s banter.’

‘It needs to stop. It’s not a joke. Someone like Georgia who doesn’t know any better will take it seriously, and I’ve had enough of it. You know it’s not true and you know there are a lot of people who’d like to believe that it is.’

‘You can’t live your life worrying about what other people think.’

‘Spoken like someone who doesn’t ever have to worry about it.’

‘You don’t have to. That’s my point. You’re choosing to care.’ He shrugged. ‘These people aren’t worth getting upset about. If they want to think the worst of you, they will, whether I say anything or not.’

‘Maybe, but you don’t have to throw fuel on the fire.’ Frustration was a knot in my stomach. It was impossible to explain how I felt to Derwent, and he didn’t have the imagination to put himself in my shoes. The gulf between his life and mine was unbridgeable. ‘You have no idea what it’s like to have to prove yourself over and over again,’ I said at last.

He rolled his eyes. ‘I have a fair idea.’

‘Because I’ve told you before. And yet, here we are, having the same conversation all over again.’ I turned away from him and squashed the teabag against the side of the mug, viciously. When I flicked the teabag at the bin I had the very small satisfaction that it went in first try.

‘I’ll keep it in mind,’ Derwent said at last. He almost sounded sincere. He would never admit he had been wrong, though, and nor would he apologise.

‘Thanks for being so understanding.’ I poured the milk into my tea and watched little white specks bob to the surface. ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake, who puts gone-off milk back in the fridge?’

‘Poor Kerrigan. It’s not your day,’ Derwent said, and left, whistling as he went.

I leaned against the wall, defeated. I was tired and cold and fed up. All I’d wanted was a hot bath, a good meal and an early night. Instead I had nothing to look forward to but a long evening on my own, reading about someone else’s investigation and some very dead women. Not my day, not my week, not my year.

5 (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

I had read the files and looked at the photographs until my eyes burned; I had watched the CCTV that the first investigation had painstakingly located and analysed. I knew the circumstances of Sara Grey’s disappearance inside out. Still, as Derwent drove down the Westway, I felt my pulse getting faster. Sara Grey. Victim one, chronologically.

‘Bloemfontein Road is coming up on the left. Not this one, the one after.’

Derwent slowed to make the turn.

‘This was where the tyre gave up.’

‘Puncture?’

I nodded. ‘They never worked out where she picked up the nail. There was nothing forensically interesting about it. Probably bad luck rather than Leo Stone’s planning. We have CCTV of her here, turning into Bloemfontein Road.’

‘Tell me about her.’

‘Sara Grey was twenty-nine at the time of her disappearance. She was engaged to Tom Mitchell, who was the same age as her. She was a primary school teacher; he had his own property development company.’

‘Did they ever check to see if he had employed Leo Stone?’

‘I didn’t see anything about it in the files.’ I scrawled a note to myself to look into it. ‘He was in Latvia on a stag weekend when it happened. Otherwise he’d have been suspect number one.’

‘Being out of the country doesn’t let him off the hook as far as I’m concerned. It’s a bit too convenient.’

‘Poor guy. If he’d been in the UK you’d be even more convinced he was involved.’

‘It’s always the husband. Or the fiancé. Or the boyfriend. Or the ex.’

‘Not this time. The original investigation focused on Tom, though, before her disappearance was linked to the others. They were looking for money worries or secret affairs or any kind of motive. They didn’t find anything.’

Derwent grunted, not convinced.

I leafed through my notes. ‘There was nothing to say Sara was being stalked – no concerns for her safety, no threats. On the day she disappeared no one was following her – at least as far as the investigators could determine.’

Derwent had slowed down to a crawl, creeping down Bloemfontein Road. ‘So what happened then?’

‘She parked just where that Volvo is. It was eleven at night but it was a Saturday, a summer night. There was a lot of traffic on the main road and there were people around. It was a warm evening – there’d been thunderstorms earlier but it was clearing up. When she got out of her car, she was seven hundred and eighty yards away from her home at 37 Haddaway Road.’

Today the light was flat, the clouds brooding over our heads. It was hard to imagine the street wrapped in the dark heat of a humid summer night.

Derwent pulled in a few cars ahead of the Volvo and parked. ‘Then what?’

‘Then she sent a text message to her fiancé telling him what had happened.’ I flipped to the relevant page and read it out. ‘Flat tyre!!! I don’t know what to do.’

‘The poor bloke was in Latvia. How was he supposed to come to the rescue?’

‘She probably just wanted to tell someone what had happened.’

‘No, she wanted to make him feel guilty for being off on a stag weekend instead of here.’

I raised my eyebrows at him. ‘That’s a very jaundiced view, even for you.’

‘She was high maintenance. I have limited patience for that.’

Melissa, Derwent’s girlfriend, was not the sort of person who would be low maintenance. If it had been anyone else I might have said as much, but Derwent had made it clear time and time again that while my personal life was endlessly entertaining, his was not available for discussion. Beside me, Derwent drummed his fingers on the steering wheel, as if he knew what I was thinking. ‘Then what happened?’

‘He replied: “Oh shit. Where r u? How bad is it? Driveable?” Obviously it wasn’t. She checked their AA membership and discovered it had lapsed so she decided to walk home. She sent him a message to that effect at 23.15.’ I showed Derwent the relevant page.

I can’t drive it. Left the car on Bloem Rd and I’m walking home. You can sort it out when you get back tomorrow.

<3 <3

Derwent grimaced. ‘Something for him to look forward to.’

‘He replied, “Typical! Call me when you get in.”’ I flipped the page. ‘According to this, “No further calls were made or received from Miss Grey’s phone and no further messages were sent by her. Mr Mitchell did not hear from his fiancée again after the message sent at 23.14. Cell site analysis revealed the phone remained switched on for a further twenty minutes, at which point it was powered down. Mr Mitchell informed police that it was highly unusual for Miss Grey to turn her phone off.”’

Derwent peered out of the car. ‘It looks like a safe enough area.’

‘It is. And they’d lived here for a year. She knew exactly where she was and she knew the quickest way home was going to be on foot.’

‘She should have been safe here.’ After a moment, he focused on me again. ‘So what route did she take?’

‘We don’t know.’ I pulled out a map I’d printed off. ‘This is Haddaway Road where she was heading. The direct route is along this road here, Haigh Road, leading into Radcliffe Road.’

‘Any reason to think she didn’t go that way?’

‘A bit of her mobile phone handset was found on Radcliffe Road in a hedge.’

‘OK. Sounds promising.’

I flattened the map out and pointed to a star I’d drawn. ‘It was here. Quite a long way from the path. I wonder if it was thrown out of a moving vehicle.’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘This sighting of a couple arguing.’ I leafed through the file and pulled out the witness statement. ‘The witness was a Mrs Hamilton. She lives on Cordray Road, here.’ I showed him where it was on the map. ‘She was driving home and happened to glance along a side street in this area – she couldn’t be specific about which street it was but it was somewhere off Simpson Road.’

Simpson Road was about a quarter of a mile south of Haigh Road. ‘That’s way off the route she should have been taking,’ Derwent said.

‘Exactly. It was around the right time though. The investigators spent a lot of time trying to get Mrs Hamilton to remember anything else but she wasn’t a great witness, reading between the lines. She got more and more confused and in the end she said she couldn’t be sure of anything she’d told them. She withdrew her statement.’

Derwent groaned. ‘Good work, lads.’

‘It was a dark night, she was driving, she glanced down a side street and sort of saw two people who might have been arguing. It wasn’t going to make or break the case even if she remembered every detail.’

‘What did she say about the man?’

‘Nothing. He was standing behind a white van. She didn’t see more than the back of his head.’

‘Leo Stone’s pretty distinctive. He’s tall, for one thing. She’d have noticed that, surely.’

‘She said not. All she could say was that he was taller than the woman.’

‘How tall was Sara Grey?’

‘Five two.’

‘Right, so my nan would be taller than her.’

‘Yeah. It wasn’t altogether helpful testimony. Wrong place, right time, few details.’ I tapped my pen on the map. ‘The van, though.’

‘I like the van.’

‘We all like the van. It’s one of the only points of comparison we’ve got, apart from where the body ended up and how it was left, and that’s Dr Hanshaw’s territory.’ I didn’t need to say the rest because Derwent knew as well as I did that if that was called into question, we could lose Sara Grey altogether. The pathologist’s evidence was a big part of what had put Leo Stone behind bars. Without it, he could walk for good.

Derwent opened his door. ‘Let’s follow her route. Work out the timings. What time did Mrs Hamilton see the arguing couple?’

‘Half past eleven.’

‘So how long did she have to get there?’

‘Fifteen minutes or so.’

He looked me up and down. ‘Your legs are about twice as long as Sara Grey’s. You’ll have to take baby steps.’

Even with Derwent slowing me down (‘Oi, giraffe, put the brakes on’) it was possible to walk as far as Simpson Road in fifteen minutes. The area was middle-class, quiet, the houses well kept. It had been two and a half years since Sara Grey disappeared and there was no point in looking for evidence but I imagined her walking home, moving fast, her head down, and I wondered how she could have ended up so far off course. For once, Derwent was thinking the same as me.

‘Why would you go this way?’ He pulled the map out of my hand and studied it, frowning. ‘If we assume Mrs H was right about what she saw.’

‘These are busier roads than the direct route. Maybe she wanted to stay where there were more people around. Alternatively, something was making her uneasy. If someone was following her, she might have taken a different route home, trying to shake them off.’

‘Wouldn’t she have wanted to go straight home? Get indoors where she was safe?’

‘Not if she was concerned about them knowing where she lived. She’d never feel safe again if she led them to her door, even if she made it inside without coming to grief.’

Derwent shook his head and walked away.

‘What?’

‘Just …’ He swung back to face me. ‘What a way to live, that’s all. Working out what risks to take. Who to trust. Walking fifteen minutes out of your way to give yourself a better chance of making it home in one piece.’

‘That’s life, isn’t it? What’s the alternative? Staying at home?’

‘Maybe.’

‘You’re not serious.’ I folded my arms. ‘If anyone should stay at home, it’s men. They’re the ones who cause most of the trouble.’

‘Like that’s going to happen.’

‘Well, women shouldn’t have to hide away either.’

‘It’s for your own good.’

‘You have to live,’ I said quietly. ‘You look over your shoulder. You check who else is in your train carriage. It’s second nature – like looking both ways when you cross the road.’

‘I don’t always look both ways.’

‘I know.’ I had hauled him back onto the pavement out of harm’s way more than once. ‘I can’t decide if it’s male privilege in action or reckless stupidity.’

‘Bit of both.’

I started walking back towards the car. ‘Let’s assume for a minute that Leo is our killer. What was he doing here? He doesn’t seem to have any connection with the area. He didn’t grow up here. He never lived here. So why go hunting here?’

‘Good point.’ Derwent looked around. ‘This is the sort of area you’d only visit if you had a reason to. What are we close to? Westfield?’

We weren’t too far from the giant shopping centre that was one of the main attractions of west London. ‘I don’t know if Stone is a big shopper. Hammersmith Hospital is the other side of the Westway. And so is HMP Wormwood Scrubs.’

‘Did he ever do time there?’

‘I don’t know. I’ll check. And I’ll check if he visited anyone there.’

‘You think he didn’t act alone?’

‘It’s one possibility,’ I said. ‘At the moment, I don’t feel as if I know anything about him.’

‘Maybe he followed her off the Westway. If he saw the flat tyre he’d have known she was in trouble. Offer to help – Bob’s your uncle.’

‘They checked the CCTV and didn’t see it. The only person who saw a van was Mrs Hamilton.’

‘And she didn’t get the VRN.’

‘What do you think?’

Derwent sighed. ‘All this time in the job and I’ve never had a single witness with a photographic memory.’

‘Me neither.’

‘They must exist.’

‘They’re too busy passing exams and winning pub quizzes to be witnesses.’ I thought for a second. ‘He had the van. Where was he working when this murder took place?’

‘You should find out.’

‘I should, and I will.’

Derwent stopped beside the car and stretched. ‘So this is the last place anyone saw her alive. When did they find her body?’

‘A long time later. She disappeared on the twelfth of July 2014, and her body was found in December. And the only reason it was discovered was because Willa Howard’s body was dumped in the same nature reserve. A visitor to the reserve found Willa, and then DCI Whitlock’s team searched the rest of the area. They were the ones who located Sara’s remains. That’s when it became clear that Leo Stone was responsible for Sara’s death as well as Willa’s.’

His forehead crinkled as he considered it. ‘Even though there’s basically nothing in the way of physical evidence or eyewitness testimony.’

‘Leo has always sworn blind he had nothing to do with Sara Grey’s disappearance.’

‘He would.’

‘He convinced her parents he was innocent.’

Derwent shook his head. ‘Then they’re as gullible as their daughter was.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/jane-casey/cruel-acts/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Jane Casey

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1503.96 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From award-winning author Jane Casey comes another powerful Maeve Kerrigan crime thriller which will keep you on the edge of your seat until the final page!How can you spot a murderer? Leo Stone is a ruthless killer – or the victim of a miscarriage of justice. A year ago, he was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. But now he’s free, and according to him, he′s innocent. DS Maeve Kerrigan and DI Josh Derwent are determined to put Stone back behind bars where he belongs, but the more Maeve finds out, the less convinced she is of his guilt. Then another woman disappears in similar circumstances. Is there a copycat killer, or have they been wrong about Stone from the start?