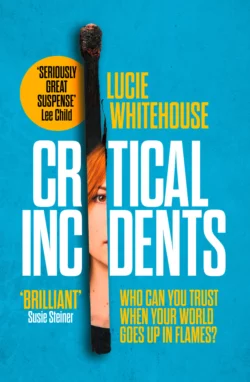

Critical Incidents

Lucie Whitehouse

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1552.23 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Who can you trust when your world goes up in flames?A gripping, sensational new crime drama, from the bestselling author of Before We Met.Detective Inspector Robin Lyons is going home.Dismissed for misconduct from the Met’s Homicide Command after refusing to follow orders, unable to pay her bills (or hold down a relationship), she has no choice but to take her teenage daughter Lennie and move back in with her parents in the city she thought she’d escaped forever at 18.In Birmingham, sharing a bunkbed with Lennie and navigating the stormy relationship with her mother, Robin works as a benefit-fraud investigator – to the delight of those wanting to see her cut down to size.Only Corinna, her best friend of 20 years seems happy to have Robin back. But when Corinna’s family is engulfed by violence and her missing husband becomes a murder suspect, Robin can’t bear to stand idly by as the police investigate. Can she trust them to find the truth of what happened? And why does it bother her so much that the officer in charge is her ex-boyfriend – the love of her teenage life?As Robin launches her own unofficial investigation and realises there may be a link to the disappearance of a young woman, she starts to wonder how well we can really know the people we love – and how far any of us will go to protect our own.