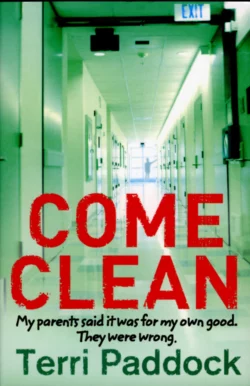

Come Clean

Terri Paddock

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская проза

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 305.03 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Mesmerising, moving novel from an exceptional author about one girl’s struggle to cope after being wrongly admitted to a boot-camp-style rehabilitation centre. A powerful and page-turning read.Justine is trying to cope with the desperate loneliness she feels now her twin brother, Joshua, no longer lives at home. After trying to drown her feelings with her first ever experiment with alcohol, she is woken early by her mother one Sunday morning. Bundled into the car by her livid parents, Justine is driven to Come Clean, a rehabilitation centre for drug addicts and alcoholics. Confused, vulnerable and covered with vomit from her first hangover, Justine is forcibly admitted to cure her “addiction”.There she begins a strict boot-camp routine of humiliation and discipline, where they attempt to strip her of her identity in order to rebuild her a better person. Justine escapes the daily torture at the centre by talking to Joshua in her head, reflecting back on their childhood and trying to puzzle out why her brother was a tortured soul… and why he chose to leave her.Because of the intensely personal nature of the narrative, this book engages the reader instantly and, however tough the subject matter, it is a real page-turner. At its heart, Come Clean is about a girl′s inability to deal her grief and her family’s ignorance of her pain. Justine shows strength, resilience, courage and hope while living a nightmare reality.This is a book which should and will attract controversy, as teenagers and society struggle to identify the problems and the treatment for drug and other teenage addictions.