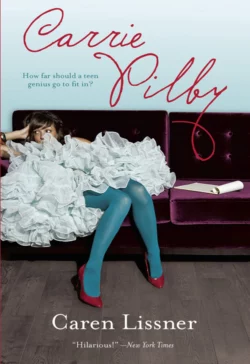

Carrie Pilby

Caren Lissner

Teen Genius (and Hermit) Carrre Pilby’s To-Do List:1. List 10 things you love (and DO THEM! ) 2. Join a club (and TALK TO PEOPLE! ) 3. Go on a date (with someone you actually LIKE! ) 4. Tell someone you care (your therapist DOESN’T COUNT! ) 5. Celebrate New Year’s (with OTHER PEOPLE! )Seriously? Carrie would rather stay in bed than deal with the immoral, sex-obsessed hypocrites who seem to overrun her hometown, New York City. She’s sick of trying to be like everybody else. She isn’t! But when her own therapist gives her a five-point plan to change her social-outcast status, Carrie takes a hard look at herself—and agrees to try.Suddenly the world doesn’t seem so bad. But is prodigy Carrie really going to dumb things down just to fit in? How far should a teen genius go to fit in?

My plan to fulfill #3 on my To-Do list, Go on a Date:

PRODIGY SEEKS GENIUS—SWF, 19, very smart, seeks nonsmoking, nondrugdoing very very smart SM 18-25 to talk about philosophy and life. No hypocrites, religious freaks, macho men or psychos.

I can’t wait to see the responses I get.

Praise for Carrie Pilby

“Smart, fresh and totally hilarious—you’ll be rooting for Carrie from start to finish.”

—Lauren Barnholdt, author of Two-Way Street

“If you’re looking for a comic commentary on school, parents, growing up and everything else, read this book.”

—Buffalo News

“[Carrie] is utterly charming and unique, and readers will eagerly turn the pages to find out how her search for happiness unfolds.”

—Booklist

“Woody Allen–hilarious, compulsively readable and unpretentiously smart.”

—Philadelphia Weekly

Carrie Pilby

Caren Lissner

www.miraink.co.uk (http://www.miraink.co.uk)

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Acknowledgments

Chapter One

Grocery stores always give me a bag when I don’t need one, when I’ve bought just a pack of gum or a banana or some potato chips that are in a bag already, and then I feel guilty about their wasting the plastic, but the bag is on before I’ve noticed them reaching for it so I don’t say anything. But in the video store, on the other hand, they always ask if I want a bag, and even though, theoretically, I should be able to carry my DVD without a bag, and the bag is another waste of plastic, I always need a bag at the video store because, for reasons that will soon be understood, I believe all DVDs should be sheathed.

The camouflage doesn’t work today. I’m only half a block out of the store when I see Ronald, the rice-haired Milquetoast who works at the coffee shop around the corner, approaching. “Hey, Carrie,” he says, looking down at my DVD. “What’d you get?”

Uh-oh. I have to give this speech again.

“I can’t tell you,” I say, “and there’s a reason I can’t. Someday, I might want to rent something embarrassing, and I don’t necessarily mean porn. It could be a movie that’s considered too childish for my age or something violent or maybe Nazi propaganda—for research purposes, of course—and even though the movie I have in my hand is considered a classic, and nothing to be ashamed of, if I show it to you this time but next time I can’t, then you’ll know for sure that I’m hiding something next time. But if I never tell you what I’ve rented, it puts enough doubt in your mind that I’m hiding something, so I can feel free to rent porn or cartoons or fascist propaganda or whatever I want without fear of having to reveal what I’ve rented. The same goes for what I’m reading. I want to be able to pick a mindless novel, as well as Dostoyevsky. And I also want to be able to choose something no one’s heard of. Most of the time, people say, ‘What are you reading?’ and if I tell them the name of the book and it’s not Moby Dick, they’ve never heard of it so I have to give an explanation, and if the book’s any good it’s not something I can explain in two seconds, so I’m stuck giving a twenty-five-page dissertation and by the time I’m done I have no time to finish reading. So books I read and movies I rent are off-limits for discussion. It’s nothing personal.”

Ronald stands there blinking for a second, then leaves.

My rules make perfect sense to me, but people find them strange. Still, I need them to survive. This world isn’t one I understand completely, and it doesn’t understand me completely, either. People think I’m odd for a nineteen-year-old girl—or woman, if you’re technical—that I neither act excessively young nor excessively “girlish.”

In truth, I feel asexual a lot of the time, like a walking brain with glasses and long dark hair and a mouth in good working order. If we were to talk about sex as in sex, as opposed to gender—as everyone seems to want to these days—I would say that my mind’s not on sex that much, and I was never boy-crazy when I was younger. Which makes me different from just about everyone. I did have crushes on two of my professors in college, one of which actually turned into something, but that’s a story for later on. That whole saga only confused me in the end. So much of the world is sex-obsessed that it takes someone practically asexual to realize just how extreme and pervasive it is. It’s the main motivator of people’s activities, the pith of their jokes and the driving force behind their art, and if you don’t have the same level of drive, you almost question whether you should exist. If it’s sex that makes the world go around, should the world stop for those of us who are asexual?

I graduated from college a year ago, three years ahead of my peers, and now I spend most of my time inside my apartment in the city. My father pays my rent. I could leave the house more, and I could even get a job, but I don’t have much motivation to. My father would like me to work, but he has no right to complain. I remind him that it was his idea to skip me three grades in grammar school, forever putting me at the top of my class academically, in the bottom fifth heightwise, and in the bottom twenty-second socially.

My father is also the one who told me what I refer to as the Big Lie. But that, like all the business with my professor, is a story for later on.

When I get back to my apartment building, Bobby, the superintendent, asks how I’m doing, then takes the opportunity to stare at my rear end. I ignore him and climb the front steps. Bobby’s always staring at my rear end. He is also too old to be named Bobby. There are some names that a person should retire after age twelve. Sally, for example. If Sally is your name, you should have it changed upon reaching puberty. Grown men should not be called Joey, Bobby, Billy, Jamie or Jimmy. They can be Harry until the age of ten and after fifty, but not between. They can be Mike, Joe and Jim all their lives. They cannot be Bob during their teenage years. They can be Stuart, Stefan or Jonathan if they’re gay. Christian is not acceptable for Jews. Moishe is not acceptable for Christians. Herbert is not acceptable for anyone. Buddy is good for a beagle. Matt is good for a flat piece of rubber. Fox is good for a fox. Dylan is too trendy.

I get in through the front door and the stairwell door and the apartment door. When I am finally inside, I experience tremendous afterglow. They make the apartments in New York as hard to get into as Tylenol bottles and almost as big.

I see a therapist, Dr. Petrov, once a week. He and my father grew up in London together. I don’t really need to see him, but I go each week because I might as well get my father’s money’s worth.

The morning after I rent the DVD, I leave my apartment to see Petrov. It’s drizzling softly outside. The air, a soupy mess, scrubs my cheeks, and the few remaining leaves on the trees bend under the weight of raindrops and dive to their deaths. A pothole in front of my building catches them, emitting a soggy symphony.

There’s something I love about visiting Petrov: His building is on one of those quaint little blocks that almost make you forget how seedy other parts of New York can be. Both sides are lined with stately brownstones whose bright painted shutters flank lively flower boxes, the tendrils dripping down and hooking around wires and trellises. The signs on the sidewalk are extremely polite: Please Curb Your Dog; $500 Fine For Noise Here. It’s idyllic and lovely. But the only people who get to live here are the folks who inherited these rent-controlled apartments from their rich old grandmas who wore tons of jewelry and played tennis with Robert Moses.

Petrov’s waiting room is like a cozy living room, with a gold-colored trodden carpet and regal-footed chairs. One wall is lined with classic novels, a pointless feature since one does not have the time to read Ulysses while waiting for a doctor’s appointment. A person would have to make more than 300 visits to Petrov in order to finish the book, which just proves that someone would have to be crazy to read all of Ulysses. But a waiting room is not the proper place or situation to read any book. All books have a time and a place. Anything by Henry Miller, for instance, should be read where no one can see you. Carson McCullers should be read in your window on a hot summer night. Sylvia Plath should be read if you’re ready to commit suicide or want people to think you’re really close.

On Petrov’s coffee table, there’s more literature: the L.L. Bean catalogue, Psychology Today, the Eddie Bauer catalogue, the Pfizer annual stockholders’ report. I admire Petrov’s ability to incorporate his junk mail into his profession.

The door to Petrov’s office opens, and a short guy walks out, lowering his eyes as he hurries past me. No one I’ve ever passed coming into this office has made eye contact with me, as if it’s embarrassing to be caught coming from a therapy appointment by someone who is about to do exactly the same thing.

Petrov stands in his doorway. “How are you doing today, Carrie?” he asks, waving me inside. There are books piled high on his desk and diplomas on the wall. Petrov sits down in a red chair and balances a yellow legal pad on his knee. I sink into the reclining chair opposite him.

“I’m fine.”

“Did you make any new friends this week?”

I think my father put this theme into his head. I don’t have many friends, but there’s a good reason for this, which I’ll explain in the near future.

“It rained this week,” I tell him, “so mostly I stayed inside.”

Petrov’s hand flutters across the page. What could he be writing? It did rain all week.

“So you haven’t been outside your apartment much. What about this coming week? Do you have any social plans?”

“I have a job interview today,” I say. “Right after this appointment.”

“That’s wonderful!” he says. “What kind of job?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “The interview’s with some guy my dad knows. I’m sure it’ll be mindless and pointless.”

“Perhaps by going in thinking that, you’ll cause it to be so.”

“If you’re trying to say it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy, that’s psychobabble,” I say. “If I tell you that the job might turn out to be mindless, then it might, or it might not. The outcome really has no relationship to whether I’ve said it.”

“It might,” Petrov says. “You put the suggestion out there.” He leans back in his chair. “I think you often thwart yourself. Let’s look at how you do it with friendships. Whenever you have met someone, you then tell me that the person was unintelligent or a hypocrite. Perhaps you have too narrow a definition of smart or too wide a one for hypocrite. There are some people who are very street-smart.”

“You can’t have an intelligent discussion with street smarts,” I say. “And even if I could find other people who are smart, they’d probably still be hypocritical and dishonest.”

It’s true. I went to college with a lot of supposedly smart people, and they’d rationalize the stupid, dangerous or hypocritical things they did all the time: getting drunk, having sex with lots of different people, trying drugs. Nobody did any of that in the beginning of school, but once the temptation started, my classmates got sucked in, then began making excuses for it. Even the self-possessed religious kids came up with ridiculous rationalizations. If they want to believe in certain things, fine, and if they don’t want to, that’s fine, too, but they shouldn’t lie to themselves about their reasons for changing their minds. The hypocrisy isn’t any better out of school, especially in the city.

“I want you to tell me something positive right now,” Petrov says. “About anything. Tell me something you love. As in, ‘I love a sunset.’ ‘I love Miami Beach.’”

“I love it when people sound like Hallmark cards.”

Petrov sighs. “Try harder.”

“Okay.” I think about it a bit. “I love peace and quiet.”

He looks at me. “Go on.”

“I guess you missed the point.”

He sighs again. “Give me another example.”

“I love…when I can just stretch out in my bed, hearing no horns, no chatter, no TV, nothing but the buzz of the electrical wiring in the wall. But sometimes I like the sounds from the street.”

“I like that,” Petrov says. “Now, tell me something that makes you sad. Something besides hypocrites and people who aren’t smart. Tell me about a time recently when you cried.”

I think. “I haven’t cried in a long time.”

“I know.”

I hate when Petrov thinks he knows things about me without my telling him. “How do you know?”

“Because you’re guarded. Because you were put into college at fifteen, when everyone was three to seven years older than you, and at fifteen, you weren’t socially advanced or sexually aware. All kinds of behavior goes on at college, people drinking, losing their virginity right and left, experimenting with who knows what. Some people respond by trying to fit in, but you chose to opt out of the system completely. Which was understandable. But now, you’ve been out of college a year and you’re still not experienced in adjusting to social changes. Being smart doesn’t mean being skilled at social interaction. No one ever said being a genius was easy.”

I hear it start to rain harder outside. Petrov gets up, shuts the window and sits back down.

“You’ve mentioned your father’s Big Lie a few times,” he says. “I think we should talk about that sometime.”

“Yes—”

“But not today. I have an assignment for you.”

I look at the rug. It’s full of tiny ropes and filaments.

“I want you to, just for a little while, be a little more social. Just to see the other side of it, to determine if there is such thing as a comfortable middle ground. I don’t want you to do anything dangerous or immoral, but I want you to do things like go to a party, join an organization or club. After you do some of these things, I want you to tell me how you felt doing them. You don’t have to start right away. You can wait a bit until you feel comfortable.”

“Okay. How about next year?”

Petrov smiles. “That’s not a bad idea,” he says. “New Year’s Eve would be a good night for you to spend time with friends. You could go to a New Year’s Eve party.”

“Maybe I should just vomit on Times Square,” I say. “Then I’d be fitting in.”

Petrov shakes his head. “You know I’m not suggesting you do anything dangerous. But I do want you to learn to socialize better. What you should do is work up to spending New Year’s Eve with people. We’ll start small first. A five-point plan.”

Petrov grabs a memo cube that has Zoloft embossed at the top. Some people will take anything if it’s free.

“First,” he says, “I want you to write a list for me of ten things you love. The street sounds were a good start, but I want ten of them. Secondly, I want you to join at least one organization or club. That way, you might meet some people with similar interests, maybe even people you think are smart.” He’s writing this down. “Third, go on a date…”

“Okay…”

“Fourth, I want you to tell someone you really care about him or her. It can’t be sarcastic.”

“Sarcastic? Me?”

Petrov tears off a piece of paper and hands it to me.

ZOLOFT®

1 List 10 things you love

2 Join an org./club

3 Go on date

4 Tell someone you care

5 Celebrate New Yr’s

“The point’s to help you adjust,” he says. “Not to teach you to do anything bad. But to help you see that there could be positive aspects of social interaction.”

“I wouldn’t have such trouble adjusting to the world,” I say, “if the world made sense. Which it doesn’t. I’ve seen that time and time again. Maybe the world should adjust to me.”

“Just try,” he pleads. “When you meet someone new, for instance, don’t…”

“What?”

“Don’t pontificate.” He scratches his goatee. “Don’t feel the need to show off everything you know at the same time, or make every argument that’s in your head.”

“If I’m not comfortable saying what I’m thinking, then isn’t the person wrong for me? And if they don’t like me, isn’t it better I find out sooner? Besides, if I say what I believe, this way we find out right away if we’re compatible.”

He blinks for a minute. “It’s good to meet compatible people, but you don’t have to hit them with tests all at once.”

I shrug. “I’ll think about it.”

He nods. “Just try.”

When I get outside, I pull my coat over my head to ward off the pouring rain, and I run to the subway. I am dying to get home, slide under the sheets and doze off. But I can’t. I have a job interview.

As I get close to the subway, a guy in a raincoat seethes at me, “Smile!”

This makes me feel worse. I was lost in thought, minding my own business, and someone felt he had the right to disturb me anyway. Doesn’t he realize that by making me feel like I was doing something wrong, he only made me feel less like smiling? It actually had the reverse effect he intended. It’s like striking a bawling kid to stop him from crying, and we’ve all seen that done.

I don’t see what it had to do with him anyway. I never go around demanding that people change their facial expressions. How come everyone tells me what to do, but they would never let me do a tenth of the same back to them?

The café where I am to meet Brad Nickerson is two stops up. When I arrive, he’s already seated at a table. He’s got slicked-back blond hair and a nondescript face. He’s also younger than I expected, and I’m not so sure this isn’t secretly a blind date rather than a business meeting.

He stands and smiles.

“It’s good to meet you,” he says.

“Likewise.”

We both sit down. He lets one of his legs hang over the other—he has long legs—and he briefly asks me how my trip up there went. Then he turns his attention to a clipboard. “I’m just going to ask you a few questions about your qualifications.”

“All right.”

“Your father says you type,” he says.

“I have.”

“Which computers do you use?”

“In school I used Macs, Dells, Gateways, HP’s, most of the off-brand PC’s, and all of the Mac and Windows operating systems. I wish they were more compatible. If Europe accepted the Euro, why can’t our computers be a little more compatible?”

His eyes narrow. “How old did you say you were?” he asks.

“I’m nineteen.”

“You seem awfully serious for a nineteen-year-old.”

I don’t know what to say to that. Now I feel bad, just like I felt when the guy yelled “Smile.” As if I was doing something wrong simply by existing.

Brad doesn’t say anything either, only stares at me and waits. And waits. When they send people to do job interviews, they should at least make sure they’re half as competent as the people they’re interviewing.

“You could tell me what the job’s about,” I say.

“Oh!” he says. “Well, it would be, at first, sort of an administrative assistant to the boss, typing things when need be, helping with office work. But eventually it could lead to greater responsibilities.” He picks up his coffee cup. “How does that sound?”

I don’t suppose he really wants a truthful answer. “Ducky,” I say.

“Mmm-hmm.” He sips his coffee. “Mmm.” He thinks for a second. “Well, why don’t you tell me your strengths and weaknesses?”

A relevant question, at last! I say, “I try to figure out what’s right and wrong, and then I stick by it. I don’t engage in activities that are dangerous to others or myself. I try not to make judgments about people.”

“I wasn’t making a judgment about you,” he says, apropos of nothing.

“I didn’t say you were.”

We’re stuck in a stalemate again. He reverts to common ground.

“How fast do you type?”

“Sixty to sixty-five words a minute,” I say.

He doesn’t add anything.

I ask, “Would you like that in metric?”

He shrugs. “Sure.”

“Sixty to sixty-five words a minute.”

I smile, but apparently, this doesn’t pass muster as a satisfactory attempt to prove I’m not so serious. He finishes his coffee. “Well,” he says, standing and smiling, “it really was nice to meet you. We’ll probably give you a call.”

“Great,” I say, but I’m really complimenting his discretion in bringing the matter to a close.

When I’m finally home, I’m incredibly relieved. Thank God I’m out of there.

I close my bedroom door, drop my purse to the ground and strip off my moist clothes. My pants leave a red elastic mark all the way around my waist. I rub it to obliterate it. Then I drape my clothes over a chair and walk to my bed.

Now I can engage in my favorite activity in the world.

Sleeping.

My bed is a vast ocean with three fat, starchy pillows. Slowly I slide under the covers, naked. I feel the cool sheets around me. The cotton caresses my back. I close my eyes and let each notch of my spine relax.

My mind is blank now. Every part of my body is sinking and empty. I don’t have to think about anything, hear anything, say anything, feel anything, worry about anything. Everything is distilled until it is completely clear.

The roof may rain down and shower me with concrete. The forked crack in my wall may creep all the way to the ceiling. Still, I can lie here forever if I choose. There is no one to stop me.

In my bed, there are no psychologists, no job interviewers, no hypocrites. I do not have to make up lists of ways to socialize. I do not have to smile. I do not have to justify my beliefs. I don’t have to wear dress shoes. I don’t have to pledge allegiance to the flag. I don’t have to use a number two pencil. I don’t have to read the fine print. I don’t have to sell fifty boxes of mint cookies. I don’t have to be over five foot four to ride.

It is true that lying in bed is not an intellectual activity. It is true that it is nonproductive.

But when ninety-five percent of out-of-bed activities hold the possibility of pain, to be pain-free is simply the most delicious feeling in the world.

I lie there for an hour, listening to the rain type a soggy message on my windows. When the storm has subsided a bit, I lift my head.

A hint of a cherry scent curls under my nose. I don’t know where it’s coming from—maybe through the window. The scent reminds me of cherry soda, something I haven’t had in years. I think about its virulent fizz, the way it bubbles deep in one’s gut.

I picture a giant glass, dark plumes of liquid bouncing off the sides. I recall a New Year’s party my father threw when I was young, how black cherry soda was what we kids were allowed to have while the adults downed highballs. There was a kid named Ted there, and he dropped M&M’s and corn chips and peanuts into his cherry soda to make us cringe. He got so much attention from the threat of drinking it that I don’t think he actually had to do the deed.

I grab a notebook from on top of my stereo and start writing my “things I love” list for Dr. Petrov. Soon, I actually have managed to come up with a few.

1 Cherry soda

2 Street sounds

3 My bed

The best bed I ever had was one with a powder-blue canopy when I was eight. My room was great back then. It had a black shag rug, Parcheesi, a giant periodic table of the elements, a diagram of Hegel’s dialectic, a model solar system, a couple of abstract paintings, and a sextant.

4. The green-blue hue of an indoor pool

5. Starfish

6. The Victorians

7. Rainbow sprinkles

8. Rain during the day (makes it easier to sleep)

I think a little more. I’m out of ideas.

If I could write a hate list, I could fill three notebooks.

That would be fun. A list of things I hate.

I could start with the couple across the street.

The couple across the street are in their late twenties or early thirties. They’re tall and fairly professional-looking. I see them in their kitchen window more than I do outside. They always mess around in front of the oven, pinching and poking each other, and before you know it, there’s a little free-love show going on, and finally, they repair to a different room. You’d think they’d have enough respect for their neighbors to keep us out of their delirious debauchery. But that’s not the reason I hate them.

The reason I hate them is that whenever they pass me on the street, they never say hi to me. They must know I’m their neighbor. I’ve lived here for almost a year.

Then again, I never say hi to them.

I try for a little while longer, but I can’t come up with nine and ten for my list. I put the notebook down and lie in bed on my side, my hands crossed over each other like the paws of a Great Dane.

I think about Petrov’s five-point plan. Join an organization. Go on a date. Petrov must think that I’m incapable of these things. It’s not at all that I can’t do them. It’s that I choose not to.

Sure, being alone can get boring, but why should I have to force myself to go out and meet all the people who have lowered their moral, ethical and intellectual standards in order to fit in with all of the other people with low moral, ethical and intellectual standards? That’s all I would find if I went out there.

I could prove to Petrov that he’s wrong. I could show him that the problem is not with me, but with everyone else. I could do it just to prove how ridiculous it is.

Going on a date, or joining a club, will push me right into the thick of the social situations that people get into every day. I’m sure it can’t be that hard. And even if Petrov believes there is the .0001 percent chance that I’ll meet one person who understands me, more likely, I will simply be able to say that I tried.

It will be a pain, but it shouldn’t be that difficult. I will be a spy in the house of socializers. And then I will be able to prove once again to myself, as well as to Petrov, that even when I’m alone, it’s much better than going outside.

That evening the phone rings. It could be bad news. It could be my father calling to say I didn’t get the job. Or worse, it could be my father calling to say I got the job. But it also could be the MacArthur Committee calling to tell me I’ve won the Genius Grant. I jump up and catch it on the third ring.

It’s my father.

“I spoke with Brad,” he says. “He seemed to think you weren’t that interested in the job.”

“Oh, now I remember,” I say. “The vapid, immature guy.”

“I got the feeling you weren’t very nice to him.”

“I didn’t ask for the interview.”

“You have to tell me how, at some point, you are going to support yourself.”

“Right now I’m using a Sealy Posturepedic.”

“Carrie.”

“I saw Dr. Petrov this morning.”

This seems to cheer him up. “Okay. And what did he say?”

“He wants me to do some kind of socialization experiment. Go on a date. Join a club.”

“And what did you say?”

“I said I’ll try.”

“That’s what I like to hear.”

“You know, you owe me,” I say.

“Why?”

“You know why.”

Silence.

He knows I mean the Big Lie.

“I know,” he says.

“Good.”

“Well, if there was a job you might be interested in, what would it be?”

“Something where I can use my intelligence,” I say. “Something where the hours aren’t ridiculous. Something where I can sleep while others are awake and be awake while others are asleep. Something where people aren’t condescending….”

“Yes….”

“Something I don’t hate.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/caren-lissner/carrie-pilby-39774645/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Caren Lissner

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.26 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Teen Genius (and Hermit) Carrre Pilby’s To-Do List:1. List 10 things you love (and DO THEM! ) 2. Join a club (and TALK TO PEOPLE! ) 3. Go on a date (with someone you actually LIKE! ) 4. Tell someone you care (your therapist DOESN’T COUNT! ) 5. Celebrate New Year’s (with OTHER PEOPLE! )Seriously? Carrie would rather stay in bed than deal with the immoral, sex-obsessed hypocrites who seem to overrun her hometown, New York City. She’s sick of trying to be like everybody else. She isn’t! But when her own therapist gives her a five-point plan to change her social-outcast status, Carrie takes a hard look at herself—and agrees to try.Suddenly the world doesn’t seem so bad. But is prodigy Carrie really going to dumb things down just to fit in? How far should a teen genius go to fit in?