About Grace

Anthony Doerr

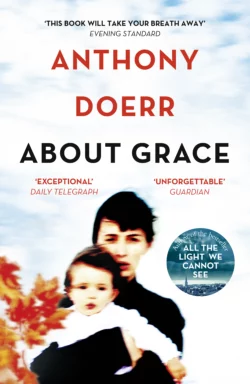

About Grace is the brilliant debut novel from Anthony Doerr, author of Pulitzer Prize-winning All The Light We Cannot See.Growing up in Alaska, young David Winkler is crippled by his dreams. At nine, he dreams a man is decapitated by a passing truck on the path outside his family’s home. The next day, unable to prevent it, he witnesses an exact replay of his dream in real life. The premonitions keep coming, unstoppably. He sleepwalks during them, bringing catastrophe into his reach.Then, as unstoppable as a vision, he falls in love, at the supermarket (exactly as he already dreamed) with Sandy. They flee south, landing in Ohio, where their daughter Grace is born. And then the visions of Grace’s death begin for Winkler, as their waterside home is inundated. Plagued by the same horrific images of Grace drowning, when the floods come, he cannot face his destiny and flees.He beaches on a remote Caribbean island, where he works as a handyman, chipping away at his doubts and hopes, never knowing whether Grace survived the flood or met the doom he foretold. After two decades, he musters the strength to find out…

About Grace

Anthony Doerr

Copyright (#ulink_5fbadb35-525e-53ac-a331-48a639bdb97b)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2005

Copyright © Anthony Doerr 2005

Extract from All the Light We Cannot See © Anthony Doerr 2014

Cover photograph © Therese/Getty Images

Anthony Doerr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operatin at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007146970

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2011 ISBN: 9780007405114

Version: 2018-10-08

Dedication (#ulink_4af544cc-dc36-57f7-a7f1-ad4268d141d6)

for my mother and father

Epigraph (#ulink_1d7bff7b-5c41-511b-a23a-4b2535345016)

There must be some definite cause why, whenever snow begins to fall, its initial formation invariably displays the shape of a six-cornered starlet. For if it happens by chance, why do they not fall just as well with five corners or with seven?…Who carved the nucleus, before it fell, into six horns of ice?

From “On the Six-Cornered Snowflake,” by Johannes Kepler, 1610

Contents

Cover (#ub25ba6d8-6a6c-58f6-a904-c1f2086874e6)

Title Page (#u2b787df5-c618-5310-aff0-22d0fae15a80)

Copyright (#u272f636a-5abf-5ff6-8d0a-de88b14a7ac2)

Dedication (#uea7d9d5e-eb73-5b6b-9dd8-84624487c1b5)

Epigraph (#u9a612477-e3d0-5cc1-a6c9-a8976861c9dd)

Book One (#ufe6583ea-5a40-55bb-bdfc-f979f14acda7)

Chapter 1 (#ud9c10d26-64a7-5d12-a7fb-b4538be7830a)

Chapter 2 (#ufc3ef7d4-2323-58e9-a585-8ba35f1f34a6)

Chapter 3 (#u8469cad6-ba0b-5804-b403-446dfc5ea05e)

Chapter 4 (#u5c735c2a-ccb5-585c-b7ff-78cdc904fc2b)

Chapter 5 (#u6f060e01-471f-587a-b149-a53dddd35297)

Chapter 6 (#u0c564a1a-f799-5840-991e-1b881c167f9a)

Chapter 7 (#u3642bff5-c6bc-5a3b-ac3f-b6308184b6ce)

Chapter 8 (#u3d817aec-b772-5545-9e47-a0e212e5db52)

Chapter 9 (#udfc2c0f2-f344-5963-a89d-d63d83183589)

Chapter 10 (#u70c72107-fc9f-5edf-baaa-bd532d260882)

Chapter 11 (#ub31b1158-470a-50d3-b3d8-4776490a1a65)

Chapter 12 (#u044afbc1-078e-501c-b892-a8aa705c9a23)

Chapter 13 (#u0a170064-4882-5215-83df-fce91eaec2c5)

Chapter 14 (#u690f5c19-40f1-5d0d-9319-cf6d3b58f939)

Chapter 15 (#u83bb50d8-6869-5bb7-ba7c-d57656536c88)

Book Two (#u5d42ad66-0b2a-5592-875b-12df128cccdd)

Chapter 1 (#u0dbdbf54-182d-582d-bc6f-d0ac904a356f)

Chapter 2 (#uf104c9e1-0b6b-59e5-8f53-89976b468f70)

Chapter 3 (#u2bde8781-85d0-5d28-a1d0-def6c5d36b7a)

Chapter 4 (#u277a1c69-32f6-508a-a85c-7eec70874705)

Chapter 5 (#ue722197b-c4cc-5a28-b653-f560e53f2df0)

Chapter 6 (#uaa7b664e-3057-5bb1-bfa6-0b6f59aa1986)

Chapter 7 (#u5446296e-1a43-5c5a-bf92-d952f6fcd064)

Chapter 8 (#ue1535ffd-e504-53de-b948-e166605e96ba)

Chapter 9 (#uf7758742-12b5-54e4-9ad0-f589277b325e)

Chapter 10 (#uf9f0507e-28c0-5981-8f80-00d76bdc0d9c)

Chapter 11 (#uc543ca6b-a3ad-5ac2-8ee4-625a6fea48dd)

Book Three (#udb921b10-3c3c-5589-9cf6-58ea6b37a133)

Chapter 1 (#u29f9b57b-b86e-54c7-b8f7-6f581bf23000)

Chapter 2 (#uf0461f0c-ee03-5799-975f-ae6a8933fac4)

Chapter 3 (#uf52a7c2a-c54e-584a-b114-76748789c3cb)

Chapter 4 (#ub4368477-40fb-5697-9c8e-927aa94ef820)

Chapter 5 (#ucee5d2a1-da8c-5128-a781-4ed97da1485a)

Chapter 6 (#uc2ca2ef3-6c50-59fb-a747-06af28d21038)

Chapter 7 (#u1a1a36ce-6865-5bd3-9e96-584e920de112)

Chapter 8 (#u038c998b-2b0c-5d30-b184-50c63022cd2c)

Chapter 9 (#u68eb44af-33fd-510a-b599-1d3a889f5460)

Chapter 10 (#uf963fbf6-c233-5cb4-b633-be55e0fae418)

Chapter 11 (#u1d3c2439-704f-5a3a-aa47-28fdd806bd9c)

Chapter 12 (#u5191a33f-0263-50cf-ac94-e3861d4c297f)

Book Four (#uc429af3c-0f88-51a3-817e-ce32d2884b44)

Chapter 1 (#u1e0e0468-5ab6-51a0-b218-75bb105529b0)

Chapter 2 (#u5de3a693-977a-57bc-acfc-5e10535dd65c)

Chapter 3 (#uccb8f5fc-ee3a-51c2-8224-f9d0f3aafc24)

Chapter 4 (#u7fef8be2-38aa-5e08-9cdb-75f9efaf6759)

Chapter 5 (#u61d34092-615f-569f-8d96-7c110945592b)

Chapter 6 (#u89907fe6-ac75-5bab-b255-29846e3c1be8)

Chapter 7 (#u58f8e8ad-4b71-5e31-aca9-8c4986d8b9bc)

Chapter 8 (#uf6f7a559-37c4-596b-977e-5cf2a6e3e62d)

Chapter 9 (#ua27849ee-1d9f-5813-b0bc-8d5210a93416)

Chapter 10 (#uc30be804-9f77-5074-8c7c-12ac81e49504)

Chapter 11 (#u68f2c9bc-2e31-54ba-9796-28f34e3b1a3f)

Book Five (#ue2931db8-fb61-5ba8-bbbb-7ddb9fe17863)

Chapter 1 (#u6886d70d-90ba-5021-a7d5-02df99b44a1c)

Chapter 2 (#u4d3911f6-c15c-5639-b7d2-1c08fc8beeb1)

Chapter 3 (#u4e287d31-14b3-50d4-8140-7f67deeb9e90)

Chapter 4 (#u72de896e-e1de-53e5-af54-86dad2ea3242)

Chapter 5 (#ua38fce2a-86b8-5a27-afb1-b58c76e6608f)

Chapter 6 (#u71cd768c-e3ef-5175-a075-80b41886835f)

Chapter 7 (#u1596e97c-b55c-5d56-aa84-50bd7e778e32)

Chapter 8 (#u774155eb-3212-536a-93f3-1717588f0efc)

Chapter 9 (#u46ea1c4b-a69c-5047-889b-fbd0e6ddeabf)

Chapter 10 (#u95806222-86f1-54f3-bf5f-d97ac17c83f7)

Chapter 11 (#u686a06fe-0fc3-5eba-a5c2-b1c17e8e2ac3)

Chapter 12 (#u62373de7-f804-500f-9dd2-12c4a51045b6)

Chapter 13 (#uebf1af18-1bac-5dd5-b762-e7436e3a16b5)

Book Six (#ua72ebbc7-c879-53f3-b0e3-4c4f86541783)

Chapter 1 (#uc4157d97-0a79-59f0-8551-5bb5c5d70beb)

Chapter 2 (#ue31eee99-380f-575a-82cd-70ce4ecd3749)

Chapter 3 (#u293bad4e-1147-58f1-9e6c-3447ecf757cb)

Chapter 4 (#u65471413-0dc1-53a7-bc0c-2a6376b42e90)

Chapter 5 (#ucae525de-2bcd-5b2d-9f11-e747c7ed0c47)

Chapter 6 (#u7dba92ba-5049-5fdb-b317-6b5b117c95d9)

Chapter 7 (#u68a55be5-d000-54d0-878f-7f27844ba872)

Chapter 8 (#u6f984183-750b-5fa3-a317-8acb71246cc4)

Chapter 9 (#ue22c7c86-e9fe-5243-9d02-270b30033d4f)

Chapter 10 (#u05783493-0664-596b-a17f-7e6f6d7e74b4)

Chapter 11 (#ubbfcaa94-3634-5aa1-ae70-786a564a02ae)

Chapter 12 (#u938e7f31-da73-5f0c-9b26-0da8575f21de)

Chapter 13 (#ue65bcd53-1a64-55c3-aba2-a734babeb519)

Chapter 14 (#u07ac2a52-5015-53cc-b9c2-cb76128225b9)

Chapter 15 (#u4a210a3a-3448-53bc-9f1a-46afd0731ff1)

Chapter 16 (#u1b56a00e-a509-5db3-8b1d-ef6655fa8047)

Chapter 17 (#uf2bb1006-687e-56a5-af51-c3e9776a29ee)

Acknowledgments (#u7362e79d-2bb0-57ee-b492-ee6a8752bf14)

All the Light We Cannot See (#u3c851a36-af56-5308-b90d-9cccc0fcdc1b)

Also by Anthony Doerr (#u046c516f-91a5-53c4-a6a3-6068b50baebb)

About the Author (#u6cbaaf1c-a2a4-555b-9bed-3ec5845ecda3)

About the Publisher (#ued241bbc-9b2f-5019-b9d1-f1b7b8a42c68)

Book One (#ulink_527f45f1-c850-57f9-9fbf-278945ca41a7)

1 (#ulink_40ca9d7e-4962-5b95-98d4-ecfbc01e24b7)

He made his way through the concourse and stopped by a window to watch a man with two orange wands wave a jet into its gate. Above the tarmac the sky was faultless, that relentless tropic blue he had never quite gotten used to. At the horizon, clouds had piled up: cumulus congests, a sign of some disturbance traveling along out there, over the sea.

The slim frame of a metal detector awaited its line of tourists. In the lounge: duty-free rum, birds of paradise sleeved in cellophane, necklaces made from shells. From his shirt pocket he produced a notepad and a pen.

The human brain, he wrote, is seventy-five percent water. Our cells are little more than sacs in which to carry water. When we die it spills from us into the ground and air and into the stomachs of animals and is contained again in something else. The properties of liquid water are this: it holds its temperature longer than air; it is adhering and elastic; it is perpetually in motion. These are the tenets of hydrology; these are the things one should know if one is to know oneself.

He passed through the gate. On the boarding stairs, almost to the jet, a feeling like choking rose in his throat. He clenched his duffel and clung to the rail. A line of birds—ground doves, perhaps—were landing one by one in a patch of mown grass on the far side of the runway. The passengers behind him shifted restlessly. A flight attendant wrung her hands, reached for him, and escorted him into the cabin.

The sensation of the plane accelerating and rising was like entering a vivid and perilous dream. He braced his forehead against the window. The ocean widened below the wing; the horizon tilted, then plunged. The plane banked and the island reemerged, lush and sudden, fringed by reef. For an instant, in the crater of Soufriere, he could see a pearly green sheet of water. Then the clouds closed, and the island was gone.

The woman in the seat next to him had produced a novel and was beginning to read. The airplane climbed the troposphere. Tiny fronds of frost were growing on the inner pane of the window. Behind them the sky was dazzling and cold. He blinked and wiped his glasses with his sleeve. They were climbing into the sun.

2 (#ulink_06791efa-c3b5-5826-abad-d4feb0f12f31)

His name was David Winkler and he was fifty-nine years old. This would be his first trip home in twenty-five years—if home was what he could still call it. He had been a father, a husband, and a hydrologist. He was not sure if he was any of those things now.

His ticket was from Kingstown, St. Vincent, to Cleveland, Ohio, with a stopover in Miami. The first officer was relaying airspeed and altitude through loudspeakers in the ceiling. Weather over Puerto Rico. The captain would keep the seat belt sign illuminated.

From his window seat, Winkler glanced around the cabin. Passengers—Americans, mostly—were reading, sleeping, speaking quietly to one another. The woman beside Winkler held the hand of a blond man in the aisle seat.

He closed his eyes, rested his head against the window, and gradually slipped into something like sleep. He woke sweating. The woman in the seat beside him was shaking his shoulder. “You were dreaming,” she said. “Your legs were shaking. And your hands. You pressed them against the window.”

“I’m all right.” Far below the wing scrolled reefs of cumuli. He mopped his face with a cuff.

Her gaze lingered on him before she took up her novel again. He sat awhile and studied the clouds. Finally, with a resigned voice, he said, “The compartment above you isn’t latched properly. In the turbulence it’ll open and the bag inside will fall out.”

She looked up. “What?”

“The compartment. The bin.” He motioned with his eyes toward the space above them. “It must not be completely closed.”

She leaned across the blond man beside her, into the aisle. “Really?” She nudged the blond man and said something and he looked over and up and said the bin was fine and latched tight.

“Are you sure?”

“Quite.”

The woman turned to Winkler. “It’s fine. Thank you.” She went back to her book. Two or three minutes later the plane began to buck, and the entire cabin plunged for a long second. The bin above them rattled, the door clicked open, and a bag dropped into the aisle. From inside came the muffled crunch of breaking glass.

The blond man lifted the bag and peered inside and swore. The plane leveled off. The bag was straw and printed with an image of a sailboat. The man began taking out pieces of what looked like souvenir martini glasses and shaking his head at them. A flight attendant squatted in the aisle and collected fragments in an airsickness bag.

The woman in the middle seat stared at Winkler with a hand over her mouth.

He kept his gaze out the window. The frost between the panes was growing, making tiny connections, a square inch of delicate feathers, a two-dimensional wonderland of ice.

3 (#ulink_d8708b60-03d5-5f7d-b54f-b6d4d8a70a2a)

He called them dreams. Not auguries or visions exactly, or presentiments or premonitions. Calling them dreams let him edge as close as he could to what they were: sensations—experiences, even—that visited him as he slept and faded after he woke, only to reemerge in the minutes or hours or days to come.

It had taken years before he was able to recognize the moment as it approached—something in the odor of a room (a smell like cedar shingles, or smoke, or hot milk and rice), or the sound of a diesel bus shaking along below an apartment, and he would realize this was an event he had experienced before, that what was about to happen—his father slicing his finger on a can of sardines, a gull alighting on the sill—was something that had already happened, in the past, in a dream.

He had standard dreams, too, of course, the types of dreams everyone has, the film reels of paradoxical sleep, all the improbable narratives concocted by a cerebral cortex working to organize its memories. But occasionally, rarely, what he saw when he slept (rain overwhelmed the gutters; the plumber offered half his turkey sandwich; a coin disappeared, inexplicably, from his pocket) was different—sharper, truer, and premonitory.

All his life it had been like this. His dreams predicted crazy, impossible things: stalactites grew out of the ceiling; he opened a door to find the bathroom stuffed with melting ice. And they predicted everyday things: a woman dropped a magazine; a cat delivered a broken sparrow to the back door; a bag fell from an overhead bin and its contents broke in the aisle. Like dreams these apparitions ambushed him in the troubled fringes of sleep, and once they were finished, they were almost always lost, disbanding into fragments he could not reassemble later.

But a few times in his life he had fuller visions: the experience of them fine-edged and hyperreal—like waking to find himself atop a barely frozen lake, the deep cracking sounding beneath his feet—and those dreams remained long after he woke, reminding themselves to him throughout the days to come, as if the imminent could not wait to become the past, or the present lunged at the future, eager for what would be. Here most of all the word failed: These were dreams deeper than dreaming, beyond remembering. These dreams were knowing.

He shifted in his seat and watched phalanxes of clouds pass below the wing. Memories scudded toward him, as distinct as the fibers in the seat-back in front of him: he saw the blue glow of a welding arc flicker in a window; he saw rain washing over the windshield of his old Chrysler. He was seven and his mother bought him his first pair of eyeglasses; he hurried through the apartment examining everything: the structure of frost in the icebox, a spattering of rain on the parlor window. What a marvel it had been to see the particulars of the world—rainbows of oil floating in puddles; columns of gnats spiraling over Ship Creek; the crisp, scalloped edges of clouds.

4 (#ulink_49d13174-ff83-57fb-9e28-b6ad0ac63f1f)

He was on an airplane, fifty-nine years old, but he could be simultaneously—in the folds of memory—a quarter century younger, in bed, in Ohio, falling asleep. The house was still and going dark. Beside him his wife slept on top of the comforter, legs splayed, her body giving off heat as it always did. Their infant daughter was quiet across the hall. It was midnight, March, rain at the windows, and he had to be up at five the next morning. He listened to the click and patter of drops against the panes. His eyelids fell.

In his dream, water swirled three feet deep in the street. From the upstairs window—he was standing at it, palms against the glass—the neighborhood houses looked like a fleet of foundered arks: flood-water past the first-floor sills, fences swallowed, saplings up to their necks.

His daughter was crying somewhere. Behind him the bed was empty and neatly made—where had his wife gone? Boxes of cereal and a few dishes stood on the dresser; a pair of gum boots waited atop the stairs. He hurried from room to room calling for his daughter. She was not in her crib or the bathroom or anywhere upstairs. He pulled on the boots and descended to the front hall. Two feet of water covered the entire first floor, silent and cold, a color like milky coffee. When he stood on the hall carpet, the water was past his knees. His daughter’s whimpering echoed strangely through the rooms, as if she were present in every corner. “Grace?”

Outside more water muttered and pressed at the walls. He waded forward. Pale spangles of reflected light swung back and forth over the ceiling. Three magazines turned idly in his wake; a bloated roll of paper towels bumped his knee and drifted off.

He opened the pantry and sent a wave rolling through the kitchen, jostling the stools. A group of half-submerged lightbulbs like the caps of tiny drifting skulls sailed toward the refrigerator. He paused. He could no longer hear her. “Grace?”

From outside came the sound of a motorboat passing. Each breath hung in front of him a moment before dispersing. The light was failing. The hairs on his arms stood up. He picked up the phone—the cord floating beneath it—but there was no dial tone. Something sour and thin was beginning to rise from his gut.

He forced open the basement door and found the stairwell entirely submerged, lost beneath a foamy brown rectangle of water. A page from a calendar floated there, something of his wife’s, a photo of a candy-striped lighthouse, darkening and turning in the froth.

He panicked. He searched for her beneath the hall table, behind the armchair (which was nearly afloat now); he looked in ridiculous places: the silverware drawer, a Tupperware bowl. He waded with his arms down, feeling below the surface, dragging his fingers along the floor. The only sounds were of his lower body splashing along and the smaller percussions of waves he’d made lapping against the walls.

He found her on his third pass through the family room. She was in her bassinet, atop the highest shelf of his wife’s plant stand, against the foggy window, her eyes wide, a blanket over her shoulders. Her yellow wool cap on her head. Her blanket was dry. “Grace,” he said, lifting her out, “who put you up there?”

Emotion flitted across her face, her lips tightening, her forehead wrinkling. Just as quickly, her expression eased. “It’s okay,” he said. “We’ll get you out of here.” He held her against his chest, waded through the hall, and dragged open the front door.

Water sighed in from the yard. The street had become a clotted, makeshift river. The sugar maple on the Sachses’ lawn was lying immersed across the street. Plastic bags, snagged in the branches, vibrated in the passage of water and sent up a high, unearthly buzzing, a sound like insects swarming. No lights were on. Two cats he had never seen before paced a low branch of the front yard oak. Dozens of possessions were adrift: a lawn chair, a pair of plastic trash cans, a Styrofoam cooler—all slathered with mud, all parading slowly down the street.

He waded down the steps of the front walk. Soon the water was to his belt and he held Grace high against his shoulder with both arms and fought the current. Her breath was small in his ear. His own breath stood out in front of them in short-lived clouds of vapor.

His clothes were drenched and he had begun to shiver. The force of water—slow, but heavy with sediment and sticks and whole clumps of turf—pushed resolutely at his thighs and he felt it trying to raise his feet and carry them away. A hundred yards up the street, behind the Stevensons’ place, a small blue light winked among the trees. He glanced back at the entrance to his own house, dark, already far away.

“Hang on, Grace,” he said. She did not cry. From the location of the telephone poles standing in the dimness he could discern where the sidewalk was and made for it.

He clawed his way up the street, hanging with one arm on to lampposts and the trunks of trees and pulling himself forward as if up the rungs of an enormous ladder. He would reach the blue light and save them. He would wake, safe and dry, in his bed.

The flood hissed and murmured, a sound like blood rising in his ears. The taste of it was in his teeth: clay and something else, like rust. Several times he thought he might slip and had to stop, propped against a mailbox, spitting water, clutching the baby. His glasses fogged. His legs and feet were numb. The flood sucked at his boots.

The light behind the Stevensons’ wavered and blinked and rematerialized as it passed behind obstacles. A boat. The water was not as deep up here. “Help!” he called. “Help us.” Grace was quiet: a small weight against his wet shirt. Far away, as if from a distant shore, sirens keened.

A few steps later, he stumbled. Water surged to his shoulders. The river pushed at him the way wind pushes at a sail and all his life, even in dreams, he would remember the sensation: the feeling of being overwhelmed by water. In a second he was borne away. He held Grace as high as he could and clamped her little thighs between his palms, his thumbs in the small of her back. He kicked; he pointed his toes and tried to find bottom. The upper halves of houses glided past. For a moment he thought they would be carried all the way down the street, past their house, past the cul-de-sac, and into the river. Then his head struck a telephone pole; he spun; the current washed them under.

The evening had gone to that last blue before darkness. He tried to hold Grace above his chest, her little hips in his hands; his own head stayed under.

His shoulders struck submerged sticks, a dozen unseen obstacles. The undercurrent sucked one of his boots off. A few hundred feet down the block they passed into an eddy, full of froth and twigs, and he threw his legs around a mailbox—the last mailbox on the street. Here the flood coursed through wooded lots at the terminus of the street and merged with the swollen, unrecognizable Chagrin River. There, somehow, he managed to stagger to his feet, still holding Grace. A spasm tore through his diaphragm and he began to cough.

The bobbing, shifting point of light that had been by the Stevensons’ was miraculously closer. “Help us!” he gasped. “Over here!”

The mailbox swiveled against his weight. The light drew nearer. It was a rowboat. A man leaned over the bow waving a flashlight. He could hear voices. The mailbox groaned against his weight. “Please,” Winkler tried to say. “Please.”

The boat approached. The light was in his face. Hands had ahold of his belt and were hauling him over the gunwale.

“Is she dead?” he heard someone ask. “Is she breathing?”

Winkler gulped air. His glasses were lost but he could see that Grace’s mouth hung open. Her hair was wet, her yellow cap gone. Her cheeks had lost their color. He could not seem to relax his arms—they did not seem like his arms at all. “Sir,” someone said. “Let her loose, sir.”

He felt a scream boiling up in his throat. Someone called for him to let go, let go, let go.

This was a dream. This had not happened.

5 (#ulink_66a2de16-cc39-5d09-acbe-0ce0885c4942)

Memory gallops, then checks up and veers unexpectedly; to memory, the order of occurrence is arbitrary. Winkler was still on an airplane, hurtling north, but he was also pushing farther back, sinking deeper into the overlaps, to the years before he even had a daughter, before he had even dreamed of the woman who would become his wife.

This was 1975. He was thirty-two years old, in Anchorage, Alaska. He had an apartment over a garage in Midtown, a 1970 Chrysler Newport, few friends, no family left. If there was anything to notice about him, it was his eyeglasses: thick, Coke-bottle lenses in plastic frames. Behind them his eyes appeared unsubstantial and slightly warped, as if he peered not through a half centimeter of curved glass but through ice, two frozen pools, his eyeballs floating just beneath.

It was March again, early breakup, the sun not completely risen but a warmth in the air, blowing east, and with it the improbable smell of new leaves, as if spring was already happening to the west—in the Aleutian volcanoes or all the way across the strait in Siberia—the first compressed buds showing on whatever kinds of trees they had there, and bears blinking as they stumbled from their hibernal dens, whole festivals starting, nighttime songs and burgeoning romances and homages to the equinox and the first seeds being sown—Russian spring blowing across the Bering Sea and over the mountains and tumbling into Anchorage.

Winkler dressed in one of his two brown corduroy suits and walked to the small brick National Weather Service office on Seventh Avenue where he worked as an analyst’s assistant. He spent the morning compiling snowpack forecasts at his little veneered desk. Every few minutes a slab of snow would slide off the roof and plunge into the hedge outside his window with a muffled whump.

At noon he walked to the Snow Goose Market and ordered a salami and mustard on wheat and waited in a checkout lane to pay for it.

Fifteen feet away a woman in tortoiseshell glasses and a tan polyester suit stopped in front of a revolving rack of magazines. Two boxes of cereal and a half gallon of milk stood primly in her basket. The light—angling through the front windows—fell across her waist and lit her shins below her skirt. He could see tiny particles of dust drifting in the air between her ankles, each fleck tumbling individually in and out of sunlight, and there was something intensely familiar in their arrangement.

A cash register clanged. An automatic fan in the ceiling clicked on with a sigh. Suddenly he knew what would happen—he had dreamed it four or five nights before. The woman would drop a magazine; he would step over, pick it up, and give it back.

The cashier handed a pair of teenagers their change and looked expectantly at Winkler. But he could not take his eyes from the woman browsing magazines. She spun the rack a quarter turn, her thumb and forefinger fell hesitantly upon an issue (Good Housekeeping, March 1975, Valerie Harper on the cover, beaming and tan in a green tank top), and she picked it up. The cover slipped; the magazine fell.

His feet made for her as if of their own volition. He bent; she stooped. The tops of their heads nearly touched. He lifted the magazine, swiped dust off the cover, and handed it over.

They straightened simultaneously. He realized his hand was shaking. His eyes did not meet hers but left their attention somewhere above her throat. “You dropped this,” he said. She didn’t take it. At the register a housewife had taken his place in line. A bagboy snapped open a bag and lowered a carton of eggs into it.

“Miss?”

She inhaled. Behind her lips were trim rows of shiny teeth, slightly off-axis. She closed her eyes and held them shut a moment before opening them, as if waiting out a spell of vertigo.

“Did you want this?”

“How—?”

“Your magazine?”

“I have to go,” she said abruptly. She set down her shopping basket and made for the exit, almost jogging, holding her coat around her, hurrying through the door into the parking lot. For a few seconds he could see her two legs scissoring up the street; then she was obscured by a banner taped over the window, and gone.

He stood holding the magazine for a long time. The sounds of the store gradually returned. He picked up her basket, set his sandwich in it, and paid for it all—the milk, the cereal, the Good Housekeeping.

Later, after midnight, he lay in his bed and could not sleep. Elements of her (three freckles on her left cheek, the groove between the knobs of her collarbone, a strand of hair tucked behind her ear) scrolled past his eyes. On the floor beside him the magazine lay open: an ad for dog biscuits, a recipe for blueberry upside-down cake.

He got up, tore open one of the cereal boxes—both were Kellogg’s Apple Jacks—and ate handfuls of the little pale rings at his kitchen window, watching the streetlights shudder in the wind.

A month passed. Rather than fade from his memory, the woman grew sharper, more insistent: two rows of teeth, dust floating between her ankles. At work he saw her face on the undersides of his eyelids, in a numerical model of groundwater data from Shemya Air Force Base. Almost every noon he found himself at the Snow Goose, scanning checkout lanes, lingering hopefully in the cereal aisle.

He went through the first box of Apple Jacks in a week. The second box he ate more slowly, rationing himself a palmful a day, as if that box were the last in existence, as if when he looked into the bottom and found only sugary dust, he’d have consumed not only his memory of her, but any chance of seeing her again.

He brought the Good Housekeeping to work and paged through it: twenty-three recipes for potatoes; coupons for Pillsbury Nut Bread; a profile of quintuplets. Were there clues to her here? When no one was looking he set Valerie Harper’s cover photo under a coworker’s Swift 2400 and examined her clavicle in the viewfinder. She consisted of melees of dots—yellows and magentas, ringed with blue—her breasts made of big, motionless halos.

Winkler, who in his thirty-two years had hardly left the Anchorage Bowl, who still caught himself some clear days staring wistfully at the Alaska Range to the north, the brilliant white massifs, and the white spaces farther back, the way they floated on the horizon less like real mountains than the ghosts of them, now found his eyes drawn into the dream kitchens of advertisements: copper pots, shelf paper, folded napkins. Was her kitchen like one of these? Did she, too, use Brillo Supreme steel wool pads for her heavy-duty cleaning needs?

He found her in June, at the same market. This time she wore a plaid skirt and tall boots. She stepped briskly through the aisles, looking different, more determined. A shaft of anxiety whirled in his chest. She bought a small bottle of grape juice and an apple, counting exact change out of a tiny purse with brass clasps. She was in and out in under two minutes.

He followed.

She walked quickly, making long strides, her gaze on the sidewalk ahead of her. Winkler had to half jog to keep up. The day was warm and damp and her hair, tied at the back of her neck, seemed to float along behind her head. At D Street she waited to cross and Winkler came up behind her, suddenly too close—if he leaned forward six inches, the top of her head would have been in his face. He stared at her calves disappearing into her boots and inhaled. What did she smell like? Clipped grass? The sleeve of a wool sweater? The mouth of the little brown bag that held her apple and juice crinkled in her fist.

The light changed. She started off the curb. He followed her six blocks up Fifth Avenue, where she turned right and went into a branch of First Federal Savings and Loan. He paused outside, trying to calm his heart. A pair of gulls sailed past, calling to each other. Through the stenciling on the window, past a pair of desks (with bankers at them, penciling things onto big desk calendars), he watched her pull open a walnut half-door and slip behind the teller counter. There were customers waiting. She set down her little bag, slid aside a sign, and waved the first one forward.

He hardly slept. A full moon, high over the city, dragged the tide up Knik Arm, then let it out again. He read from Watson, from Pauling, the familiar words disassembling in front of his eyes. He stood by the window with a legal pad and wrote: Inside me a trillion cells are humming, proteins stalking the strands of my DNA, winding and unwinding, making and remaking…

He crossed it out. He wrote: Do we choose who we love?

If only his first dream had carried him past what he already knew, past the magazine falling to the floor. He shut his eyes and tried to summon an image of her, tried to keep her there as he drifted toward sleep.

By nine A.M. he was on the same sidewalk watching her through the same window. In his knapsack he had what remained of the second box of Apple Jacks and the Good Housekeeping. She was standing at her teller’s station, looking down. He wiped his palms on his trousers and went in.

There was no one in the queue, but her station had a sign up: PLEASE SEE THE NEXT TELLER. She was counting ten-dollar bills with the thin, pink hands he already thought of as familiar. A nameplate resting on the marble counter read, SANDY SHEELER.

“Excuse me.”

She held up a finger and continued counting without looking up.

“I can help you down here,” another teller offered.

“It’s okay,” Sandy said. She reached the end of her stack, made a notation on the corner of an envelope, and looked up. “Hello.”

The lenses of her glasses reflected a light in the ceiling for a second and flooded the lenses of his own glasses with light. Panic started in his throat. She was a stranger, entirely unfamiliar; who was he to have guessed at her dissatisfactions, to have incorporated her into his dreams? He stammered: “I met you in the supermarket? A few months ago? We didn’t actually meet, but…”

Her gaze swam. He reached into his knapsack and withdrew the cereal and the magazine. A teller to Sandy’s right glanced over the partition.

“I thought maybe,” he said, “you wanted these? You left so quickly.”

“Oh.” She did not touch the cereal or the Good Housekeeping but did not take her eyes from them. He could not tell but thought she leaned forward a fraction. He lifted the box of cereal and shook it. “I ate some.”

She gave him a confused smile. “Keep it.”

Her eyes tracked from the magazine to him and back. A critical moment was passing now, he knew it: he could feel the floor falling away beneath his feet. “Would you ever want to go to a movie? Anything like that?”

Now her gaze veered past Winkler and over his shoulder, out into the bank. She shook her head. Winkler felt a small weight drop into his stomach. Already he began to back away. “Oh. I see. Well. I’m sorry.”

She took the box of Apple Jacks and shook it and set it on the shelf beneath the counter. She whispered, “My husband,” and looked at Winkler for the first time, really looked at him, and Winkler felt her gaze go all the way through the back of his head.

He heard himself say: “You don’t wear a ring.”

“No.” She touched her ring finger. Her nails were clipped short. “It’s getting repaired.”

He sensed he was out of time; the whole scene was slipping away, liquefying and sliding toward a drain. “Of course,” he mumbled. “I work at the Weather Service. I’m David. You could reach me there. In case you decide differently.” And then he was turning, his empty knapsack bunched in his fist, the bright glass of the bank’s facade reeling in front of him.

Two months: rain on the windows, a pile of unopened meteorology texts on the table in his apartment that struck him for the first time in his life as trivial. He cooked noodles, wore one of the same two brown corduroy suits, checked the barometer three times a day and charted his readings halfheartedly on graph paper smuggled home from work.

Mostly he remembered her ankles, and the particles of dust drifting between them, illuminated in a slash of sunlight. The three freckles on her cheek formed an isosceles triangle. He had been so certain; he had dreamed her. But who knew where assurance and belief came from? Somewhere across town she was standing at a sink or walking into a closet, his name stowed somewhere in the pleated neurons of her brain, echoing up one dendrite in a billion: David, David.

The days slid by, one after another: warm, cold, rainy, sunny. He felt, all the time, as if he had lost something vital: his wallet, his keys, a fundamental memory he couldn’t quite summon. The horizon looked the same as ever: the same grimy oil trucks groaned through the streets; the tide exposed the same mudflats twice a day. In the endless gray Weather Service teletypes, he saw the same thing every time: desire.

Hadn’t there been a longing in her face, locked behind that bank-teller smile—a yearning in her, visible just for a second, as she dragged her eyes up? Hadn’t she seemed about to cry at the supermarket?

The Good Housekeeping lay open on his kitchen counter, bulging with riddles: Do you know the secret of looking younger? How much style for your money do cotton separates offer? How many blonde colors found in nature are in Naturally Blonde Hair Treatment?

He walked the streets; he watched the sky.

6 (#ulink_14667648-d06b-5678-9331-79bea1137e37)

She called in September. A secretary patched her through. “He has a hockey game,” Sandy said, nearly whispering. “There’s a matinee at four-fifteen.”

Winkler swallowed. “Okay. Yes. Four-fifteen.”

She appeared in the lobby at four-thirty and hurried past him to the concessions counter where she bought a box of chocolate-covered raisins. Then, without looking at him, she entered the theater and sat in the dimness with the light from the screen flickering over her face. He took the seat beside her. She ate her raisins one after another, hardly stopping to breathe; she smelled, he thought, like mint, like chewing gum. All through the film he stole glances: her cheek, her elbow, stray hairs atop her head illuminated in the wavering light.

Afterward she watched the credits drift up the screen as if the film still played behind them, as if there would be more to the story. Her eyelids blinked rapidly. The house lights came up. She said, “You’re a weatherman.”

“Sort of. I’m a hydrologist.”

“The ocean?”

“Groundwater, mostly. And the atmosphere. My main interest lies in snow, in the formation and physics of snow crystals. But you can’t really get paid to study that. I type memos, recheck forecasts. I’m basically a secretary.”

“I like snow,” Sandy said. Moviegoers were filing for the exits and her attention flitted over them. He fumbled for something to say.

“You’re a bank teller?”

She did not look at him. “That day in the market…It was like I knew you were going to be there. When I dropped the magazine, I knew you’d come over. It felt like I had already done it, already lived through it once before.” She glanced at him quickly, just for a moment, then gathered her coat, smoothed out the front of her skirt, and peered over her shoulder to where an usher was already sweeping the aisle. “You think that’s crazy.”

“No,” he said.

Her upper lip trembled. She did not look at him. “I’ll call next Wednesday.” Then she was moving down the row of seats, her coat tight around her shoulders.

Why did she call him? Why did she come back to the theater, Wednesday after Wednesday? To slip the constraints of her life? Perhaps. But even then Winkler guessed it was because she had felt something that noon in the Snow Goose Market—had felt time settle over itself, imbricate and fix into place, the vertigo of future aligning with the present.

They saw Jaws, and Benji, talking around the edges. Each week Sandy bought a box of chocolate-covered raisins and ate them with the same zeal, the indigo light of the screen flaring in the lenses of her glasses.

“Sandy,” he’d whisper in the middle of a film, his heart climbing his throat. “How are you?”

“Is that the uncle?” she’d whisper back, eyes on the screen. “I thought he was dead.”

“How is work? What have you been up to?”

She’d shrug, chew a raisin. Her fingers were thin and pink: magnificent.

Afterward she’d stand, take a breath, and pull her coat around her. “I hate this part,” she said once, peeking toward the exits. “When the lights come on after a movie. It’s like waking up.” She smiled. “Now you have to go back to the living.”

He’d remain in his seat for a few minutes after she’d left, feeling the emptiness of the big theater around him, the drone of the film rewinding up in the projection room, the hollow thunk of an usher’s dustpan as he swept the aisles. Above Winkler the little bulbs screwed into the ceiling in the shape of the Big Dipper burned on and on.

She was born in Anchorage, two years before him. She wore lipstick that smelled like soap. She got cold easily. Her socks were always too thin for the weather. During the earthquake of ’64 a Cadillac pitched through the front window of the bank, and she had been, she confessed, thrilled by it, by everything: the sudden smell of petroleum, the enormous car-swallowing graben that had yawned open in the middle of Fourth Avenue. She whispered: “We didn’t have to go back to work for a week.”

The husband (goalie for his hockey team) was branch manager. They got married after her senior year at West High School. He had a fondness for garlic salt that, she said, “destroyed his breath,” so that she could hardly look at him after he ate it, could hardly stand to be in the same room.

For the past nine years they had lived in a beige ranch house with brown shingles and a yellow garage door. A pair of lopsided pumpkins lolled on the front porch like severed heads. Winkler knew this because he looked up the address in the phone book and began driving past in the evenings.

The husband didn’t like movies, was happy to dry the dishes, loved—more than anything, Sandy said—to play miniature golf. Even his name, Winkler thought, was cheerless: Herman. Herman Sheeler. Their phone number, although Winkler had never called it, was 542-7433. The last four digits spelled the first four letters of their last name, something Herman had, according to Sandy, announced at a Friday staff meeting as the most remarkable thing that had happened to him in a decade.

“In a decade,” she said, staring off at the soaring credits.

Winkler—behind his big eyeglasses, his solitary existence—had never felt this way, never been in love, never flirted with or thought about a married woman. But he couldn’t let it go. It was not a conscious decision; he did not think: We were meant to be, or: Something has predetermined that our paths cross, or even: I choose to think of her several times a minute, her neck, her arms, her elbows. The shampoo smell of her hair. Her chest against the fabric of a thin sweater. His feet simply brought him by the bank every day, or the Newport pulled him past her house at night. He ate Apple Jacks. He threw away his tin of garlic salt.

Through the bank window he peered at the bankers behind their desks: one in a blue suit with a birthmark on his neck; another in a V-neck sweater with gray in his hair and a ring of keys clipped to his belt loop. Could the V-neck be him? Wasn’t he twice her age? The birthmarked man was looking up at Winkler and chewing his pen; Winkler ducked behind a pillar.

In December, after they had watched Three Days of the Condor for the second time, she asked him to take her to his apartment. All she said about Herman was: “He’s going out after the game.” She seemed nervous, pushing her cuticles against the edges of her teeth, but she was perpetually nervous, and this, Winkler figured, was part of it—Anchorage was not a huge city and they could, after all, be seen at any time. They could be found out.

The streets were dark and cold. He led her quickly through the alternating pools of streetlight and shadow. Hardly anyone was out. The tailpipes of cars at stop signs smoked madly. Winkler did not know whether to take her hand or not. He felt he could see Anchorage that night with agonizing clarity: slush frozen into sidewalk seams, ice glazing telephone wires, two men hunched over menus behind a steamy diner window.

She looked at his apartment with interest: the block-and-board shelves, the old, banging radiator, the cramped kitchen that smelled of leaking gas.

She picked up a graduated cylinder and held it to the light. “The meniscus,” he explained, and pointed to the curve in the surface of the water inside. “The molecules at the edges are climbing the glass.” She set it down, picked up a typed page lying on a shelf: Imeasured spatial resolution data of atmospheric precipitable water and vapor pressure deficit at two separate meteorological stations…

“What is this? You wrote this?”

“It’s part of my dissertation. That nobody read.”

“On snowflakes?”

“Yes. Ice crystals.” He ventured further. “Take a snow crystal. The classic six-pointed star? How it looks so rigid, frozen in place? Well, in reality, on an extremely tiny level, smaller than a couple of nanometers, as it freezes it vibrates like crazy, all the billion billion molecules that make it up shaking invisibly, practically burning up.”

Sandy reached behind her ear and coiled a strand of hair around her finger.

He pushed on: “My idea was that tiny instabilities in those vibrations give snowflakes their individual shapes. On the outside the crystal looks stable, but on the inside, it’s like an earthquake all the time.” He set the sheet back on the shelf. “I’m boring you.”

“No,” she said.

They sat on his sofa with their hips touching; they drank instant hot chocolate from mismatched mugs. She gave herself to him solemnly but without ceremony, undressing and climbing onto his twin bed. He didn’t put on the radio, didn’t draw the shades. They set their eyeglasses beside each other on the floor—he had no nightstands. She pulled the covers over their heads.

It was love. He could study the colors and creases in her palm for fifteen minutes, imagining he could see the blood traveling through her capillaries. “What are you looking at?” she’d ask, squirming, smiling. “I’m not so interesting.”

But she was. He watched her sort through a box of chocolate-covered raisins, selecting one, then rejecting it by some indiscernible criteria; he watched her button her parka, slip her hand inside her collar to scratch a shoulder. He excavated a boot print she’d left on the snowy step outside his apartment and preserved it in his freezer.

To be in love was to be dazed twenty times a morning: by the latticework of frost on his windshield; by a feather loosed from his pillow; by a soft, pink rim of light over the hills. He slept three or four hours a night. Some days he felt as if he were about to peel back the surface of the Earth—the trees standing frozen on the hills, the churning face of the inlet—and finally witness what lay beneath, the structure under there, the fundamental grid.

Tuesdays quivered and vibrated, the second hand slogging around the dial. Wednesdays were the axis around which the rest of the week spun. Thursdays were deserts, ghost towns. By the weekends, the bits of herself that she had left behind in his apartment took on near-holy significance: a hair, coiled on the rim of the sink; the crumbs of four saltines scattered across the bottom of a plate. Her saliva—her proteins and enzymes and bacteria—still probably all over those crumbs; her skin cells on the pillows, all over the floor, pooling as dust in the corners. What was it Watson had taught him, and Einstein, and Pasteur? The things we see are only masks for the things we can’t see.

He flattened his hair with a quivering hand; he walked into the bank lobby shaking like a thief; he produced a store-bought daisy from his knapsack and set it on the counter in front of her.

They made love with the window open, cold air pouring over their bodies. “What do you think movie stars do for Christmas?” she’d ask, the hem of the sheet at her chin. “I bet they eat veal. Or sixty-pound turkeys. I bet they hire chefs to cook for them.” Out the window a jet traversed the sky, landing lights glowing, her eyes tracking it.

Sometimes she felt like a warm river, sometimes a blade of hot metal. Sometimes she took one of his papers from a shelf and propped herself on pillows and paged through it. “One-dimensional snowpack algorithms,” she’d read, solemnly, as if mouthing the words of a spell. “C

equals degree-day melt coefficient.”

“Leave a sock,” he’d whisper. “Leave your bra. Something to get me through the week.” She’d stare up at the ceiling, thinking her own thoughts, and soon it would be time to leave: she’d sheathe herself in her clothes once more, pull back her hair, lace up her boots.

When she was gone he’d bend over the mattress and try to smell her in the bedding. His brain projected her onto his eyelids relentlessly: the arrangement of freckles on her forehead; the articulateness of her fingers; the slope of her shoulders. The way underwear fit her body, nestling over her hips, slipping between her legs.

Every Saturday she worked the drive-up teller window. I love you, Sandy, he’d write on a deposit slip and drop it into the pneumatic chute outside the bank. Not now, she’d respond, and send the canister flying back.

But I do, he’d write, in larger print. Right now I LOVE YOU.

He watched her crumple his note, compose a new one, seal the carrier, drop it into the intake. He brought it into his car, unscrewed it on his lap. She’d written: How much?

How much, how much, how much? A drop of water contains 10

molecules, each one agitated and twitchy, linking and separating with its neighbors, then linking up again, swapping partners millions of times a second. All water in any body is desperate to find more, to adhere to more of itself, to cling to the hand that holds it; to find clouds, or oceans; to scream from the throat of a teakettle.

“I want to be a police officer,” she’d whisper. “I want to drive one of those sedans all day and say code words into my CB. Or a doctor! I could go to medical school in California and become a doctor for kids. I wouldn’t need to do big, spectacular rescues or anything, just small things, maybe test blood for diseases or viruses or something, but do it really well, be the one doctor all the parents would trust. ‘Little Alice’s blood must go to Dr. Sandy,’ they’d say.” She giggled; she made circles with a strand of hair. In the theater Winkler had to sit on his hands to keep them from touching her. “Or no,” she’d say, “no, I want to be a bush pilot. I could get one of those passbook accounts of Herman’s and finally save enough to buy a used plane, a good two-seater. I’d get lessons. I’d look into the engine and know every part, the valves and switches and whatever, and be able to say, ‘This plane has flown a lot but she sure is a good one.’”

Her eyelids fluttered, then steadied. Across town her husband was crouched in the net, watching a puck slide across the blue line.

“Or,” she said, “a sculptor. That’s it. I could be a metal sculptor. I could make those big, strange-looking iron things they put in front of office buildings to rust. The ones the birds stand on and everybody looks at and says, ‘What do you think that’s supposed to be?’”

“You could,” he said.

“I could.”

Every night now—it was January and dark by 4 P.M.—he pulled on his big parka and drew the hood tight and drove past her house. He’d start at the end of the block, then troll back up, the hedges coming up on his left, the curb-parked cars with their hoods ajar to allow extension cords into the frost plugs, the Newport slowing until he’d come to a stop alongside their driveway.

By nine-thirty each night, her lights began to go off: first in the windows at the far right, then the room next to it, then the lamp behind the curtains to the left, at ten o’clock sharp. He’d imagine her passage through the dark rooms, following her with his eyes, down the hall, past the bathroom, into what must have been the bedroom, where she’d climb into bed with him. At last only the tall backyard light would glow, white tinged with blue, all the parked cars drawing energy from the houses around them, the plugs clicking on and off, and above the neighborhood the air would grow so cold it seemed to glitter and flex—as if it were solidifying—and he’d get the feeling that someone could reach down and shatter the whole scene.

Only with great effort could he get his foot to move to the accelerator. He’d drive to the end of the block, turn up the heater, roll alone through the frozen darkness across town.

“It’s not that he’s awful or anything,” Sandy whispered once, in the middle of Logan’s Run. “I mean, he’s nice. He’s good. He loves me. I can do pretty much whatever I want. It’s just sometimes I look into the kitchen cupboards, or at his suits in the closet, and think: This is it?”

Winkler blinked. It was the most she’d said during a movie.

“I feel like I’ve been turned inside out is all. Like I’ve got huge manacles on my arms. Look”—she grabbed her forearm and raised it—”I can hardly lift them they’re so heavy. But other times I get to feeling so light it’s as if I’ll float to the ceiling and get trapped up there like a balloon.”

The darkness of the movie theater was all around them. On-screen a robot showed off some people frozen in ice. In the ceiling the little bulbs that were supposed to be stars burned in their little niches.

Sandy whispered: “I get happy sometimes for the younger gals at work, when they find love, after all that stumbling around, when they’ve found their guy and get to talking about weddings during break, then babies, and I can see them outside smoking and staring out at the traffic, and I know they’re probably not a hundred percent happy. Not all-the-way happy. Maybe seventy percent happy. But they’re living it. They’re not giving up.

“I’ve just been feeling everything too much. I don’t know. Can you feel things too much, David?”

“Yes.”

“I shouldn’t tell you any of this. I shouldn’t tell you anything.”

The film had entered a chase sequence and the varying colors of a burning city strobed across Sandy’s eyeglasses. She closed her eyes.

“Thing is,” she whispered, “Herman doesn’t have any sperm. We got him tested a few years ago. He has none. Or basically none; no good ones. When they called, they gave the results to me. I never told him. I told him they said he was fine. I tore up their letter and brought the little scraps to work and hid them at the bottom of a trash can in the ladies’ bathroom.”

On-screen Logan careened down a crowded street. Suits in the closet, Winkler thought. The guy with the birthmark?

In his memory he could traverse months in a second. He imagined Herman crouched like a crab on the ice, guarding the net, slapping his glove against his big leg pads, his teammates swirling around the rink. He imagined Sandy leaning over him, the tips of her hair dragging over his face. He stood outside their house on Marilyn Street and above the city, streamers of auroras—reds and purples and greens—glided like souls into the firmament.

Now a soft hail—lump graupels—flew from the clouds. He opened all his windows, turned off the furnace, and let it blow in, angling through the frames, the tiny balls rolling and eddying on the carpet.

Near the middle of March she lay beside him in the darkness with a single candle burning on his sill. Out beyond the window a trash collector tossed the frozen contents of a trash can into the maw of his truck and Winkler and Sandy listened to it clatter and compress and the fading rumble as the truck receded down the street. It was around five and all through the city, people were ending their workdays, mail carriers delivering their last envelopes, accountants paying one more invoice, bankers sealing their vaults. Tumblers finding their grooves.

“You ever just want to go?” she whispered. “Go, go, go?”

Winkler nodded. Without her glasses, that close to his face, her eyes looked trapped, closer to how they had looked in the supermarket, standing at a revolving rack of magazines but trembling inside; her whole body, its trillions of cells, quivering invisibly, threatening to shake apart. He had dreamed her. Hadn’t she dreamed him, too?

“I should tell you something,” he said. “About that day we met in the market.”

She rolled onto her back. In five minutes, maybe six, she would leave, and he told himself he would pay attention to every passing second, the pulse in her forearm, the pressure of her knee against his thigh. The thousand pores in the side of her nose. In the frail light he could see her boots on the frayed rug, her clothes folded neatly beside.

He would tell her. Now he would tell her. I dreamed you, he’d say. Sometimes I have these dreams.

“I’m pregnant,” she said.

The flame of the candle on the sill twisted and righted.

“David? Did you hear me?”

She was looking at him now.

“Pregnant,” he said, but at first it was only a word.

7 (#ulink_26e06de8-d3bd-59d9-8bb1-c9cf27b6804d)

He parked the Newport in a drive-up lane and tugged a deposit slip from the slot.

Can you get away?

No.

Only for an hour?

He could just make her out through the drive-up window, wearing a big-collared sweater, her head down, her hand writing. The pneumatic tube clattered and howled.

This is not the time, David. Please. Wednesday.

Between them was fifteen or so feet of frozen space, bounded by his window and hers, but it was as if the windows had liquefied, or else the air had, and his vision skewed and rippled and it was all he could do to put the Newport into gear and ease forward to let the next car in.

He couldn’t work, couldn’t sleep, couldn’t leave her alone. He went by the house every night, patrolling Marilyn Street, up and back, up and back, until one midnight a neighbor came out with a snow shovel and flagged him down and asked if he was missing something.

In Sandy’s backyard the one blue street lamp shivered. The Chrysler started away slowly, with reluctance, as if it, too, couldn’t bear to leave her.

Each time the office phone rang, adrenaline streamed into his blood. “Winkler,” the supervisor said, waving a sheaf of teletype forecasts. “These are atrocious. There are probably fifty typos in today’s series alone.” He looked him up and down. “Are you sick or something?”

Yes! he wanted to cry. Yes! So sick! He walked to First Federal at lunch but she wasn’t at her station. The teller in the station to the right studied him with her head cocked as if assessing the validity of his concern and finally said Sandy was home with the flu and could she help him instead?

The banker with the birthmark was on the phone. The gray-haired one was talking with a man and a woman, leaning forward in his chair. “No,” Winkler said. On the way out he scanned the nameplates on the desks but even with his glasses on couldn’t make out a name, a title, any of it.

She came to the door wearing flannel pajamas printed all over with polar bears on toboggans. Something about her standing in her doorway barefoot started a buzzing all through his chest.

“What are you doing here?”

‘They said you were sick.”

“How did you know where I live?”

He looked across the street to where the other houses were shuttered against the cold. Heat escaping from the hall blurred the air.

“Sandy—”

“You walked?”

“Are you okay?”

She stayed in the doorway, squinting out. He realized she was not going to invite him in. “I threw up,” she said. “But I feel fine.”

“You look pale.”

“Yes. Well. So do you. Breathe, David. Take a breath.”

Her feet were turning white in the cold. He wanted to fall to his knees and take them in his hands. “How is this going to work, Sandy? What are we going to do?”

“I don’t know. What are we supposed to do?”

“We could go somewhere. Anywhere. We could go to California, like you said. We could go to Mexico. You could become whatever you wanted.”

Her eyes followed an Oldsmobile as it passed slowly down the street, snow squeaking beneath its tires. “Not now, David.” She shook her head. “Not in front of my house.”

March ended. Community hockey ended. She consented to meet him for coffee. In the cafe her head periodically swiveled on her shoulders, checking back through the window as if she had ducked a pursuer. He brushed snow off her coat: stellar dendrites. Storybook snow.

“You haven’t been at the bank.”

She shrugged. A line of meltwater sped down one lens of her glasses. The waitress brought coffee and they sat over the mugs and Sandy didn’t speak.

He said: “I grew up over there, across the street. From the roof, when it was very clear, you could see half the peaks of the Alaska Range. You could pick out individual glaciers on McKinley. Sometimes I’d go up there just to look at it, all that untouched snow. All that light.”

She glanced again toward the window and he could not tell if she was listening. It struck him as strange that she could look pretty much how she always looked, her waist could still slip neatly into her jeans, the blood vessels in her cheeks could still dilate and fill with color, yet inside her something they’d made had implanted into the wall of her uterus, maybe the size of a grape by now, or a thumb, dividing its cells like mad, siphoning from her whatever it needed.

“What I really love is snow,” he said. “To look at it. I used to go up there with my mother and collect snow and we’d study it with magnifying glasses.” Still she did not look up. Snow pressed at the shop window. “I’ve never been with anyone, you know. I don’t even have any friends, not really.”

“I know, David.”

“I’ve hardly even left Anchorage.”

She nodded and braced both hands around her cup.

“I applied for jobs last week,” he said. “All over the country.”

She spoke to her coffee. “What if I hadn’t been in that grocery store? What if I had decided to go two hours earlier? Or two minutes?”

“We can leave, Sandy.”

“David.” Her boots squeaked beneath the table. “I’m thirty-four years old. I’ve been married for fifteen and a half years.”

Bells slung over the door handle jangled and two men came in and stamped snow from their shoes. Winkler’s eyeballs were starting to throb. Fifteen and a half years was incontestable, a continent he’d never visit, a staircase he’d never climb. “The supermarket,” he was saying. “We met in the supermarket.”

She stopped showing up at the bank. She did not pick up the phone at her house. He’d dial her number all day and in the evenings Herman Sheeler would answer with an enthused, half-shouted “Hello?” and Winkler, across town, cringing in his apartment, would gently hang up.

He trolled Marilyn Street. Wind rolled in from the inlet, cold and salty.

Rain, and more rain. All day the ground snow melted and all night it froze. Winter broke, and solidified, and broke again. Out in the hills, moose were stirring, and foxes, and bears. Fiddleheads were nudging up. Birds coursed in from their southern fields. Winkler lay in his little bed after midnight and burned.

At a welding supply store he compiled a starter kit: a Clarke arc welder; a wire brush; tin snips; a chipping hammer; welder’s gloves, apron, and helmet; spools of steel, aluminum, and copper wire; brazing alloys in little tubes; electrodes; soldering lugs. The clerk piled it all into a leftover television box and at noon on a Tuesday, Winkler drove to Sandy’s house, parked in the driveway, took the box in his arms, went up the front walk, and banged the knocker.

He knocked three times, four times. He waited. Maybe Herman had put her on a plane for Phoenix or Vancouver with instructions never to come back again. Maybe she was across town right then getting an abortion. Winkler trembled. He knelt on the porch and pushed open the mail slot. “Sandy!” he called, and waited. “I love you, Sandy! I love you!”

He got in the Newport, drove south, circled the city lakes: Connors and DeLong, Sand, Jewel, and Campbell. Forty minutes later he pulled down Marilyn past her house and the box was gone from the front porch.

Baltimore, Honolulu, and Salt Lake said no, but Cleveland said yes, handed down an offer: staff meteorologist for a television network, a salary, benefits, a stipend to pay for moving.

He drove to Sandy’s and pulled into the driveway and sat a minute trying to calm his heart. It was Saturday. Herman answered the door. He was the gray-haired one: the one with the key ring permanently clipped to his belt loop. Gray-haired at thirty-five. “Hello,” Herman said, as if he were answering the phone. Over his shoulder Winkler could just see into the hall, maple paneling, a gold-framed watercolor of a trout at the end. “Can I help you?”

Winkler adjusted his glasses. It was clear in a half second: Herman had no clue. Winkler said, “I’m looking for Sandy Sheeler? The metal artist?”

Herman blinked and frowned and said, “My wife?” He turned and called, “Sandy!” back into the house.

She came into the hall wiping her hands on a towel. Her face blanched.

“He’s looking for a metal artist?” Herman asked. “With your name?”

Winkler spoke only to Sandy. “I was hoping to get my car worked on. Whatever you like. Make it”—he gestured to his Chrysler and they all looked at it—“more exciting.”

Herman clasped his hands behind his head. There were acne scars on his jaw. “I’m not sure you’ve got the right house.”

Winkler retreated a step. His hands were shaking badly so he stowed them behind his back. He did not know if he would be able to say any more and was overwhelmed with relief when Sandy stepped forward.

“Okay,” she said, nodding. She snapped the towel and folded it and draped it over her shoulder. “Pull it into the garage. I can do whatever I want?”

“As long as it drives.”

Herman peered over Sandy’s head then back at her. “What are you talking about? What’s going on here?”

Winkler’s hands quivered behind his back. “The keys are inside. I can come back in, say, a week?”

“Sure,” she said, still looking at the Newport. “One week.”

One week. He went to Marilyn Street only once: creeping on foot through the slushy yard and peering through the garage window toward midnight. Through cobwebs he could just make out the silhouette of his car, hunkered there amid boxes in the shadows. None of it looked any different.

What had he hoped to see? Elaborate sculptures welded to the roof? Wings and propellers? A shower of sparks flaring in the rectangular lens of her welding mask? He dreamed Sandy asleep in her bed, the little embryo awake inside her, turning and twisting, a hundred tiny messages falling around it like snow, like confetti. He dreamed a welding arc flickering in the midnight, a bright orange seam of solder, tin and lead transformed to light and heat. He woke; he said her name to the ceiling. It was as if he could feel her across town, her tidal gravity, the blood in him tilting toward her.

In his road atlas Ohio was shaped like a shovel blade, a leaf, a ragged valentine. The black dot of Cleveland in the northeast corner like a cigarette burn. Hadn’t he dreamed her in the supermarket? Hadn’t he foreseen all of this?

Six days after he’d visited their house, she telephoned him, whispering down the wire, “Come late. Go to the garage.”

“Sandy,” he said, but she was already gone.

He closed his savings account—four thousand dollars and change—and stuffed whatever else he could carry—books, clothes, his barometer—into a railroad duffel he’d inherited from his grandfather. A taxi dropped him at the end of the block.

He eased the panels of the garage door up their tracks. She was already in the passenger’s seat. A suitcase, decorated with red plaid on both sides, waited in the backseat. Beside it was the television box stuffed with welding supplies: the torch still in its packaging, the boxes of studs unopened. He set his duffel in the trunk.

“He’s asleep,” she said when Winkler opened the driver’s door. He dropped the transmission into neutral and rolled the car to the end of the driveway and halfway down Marilyn Street before climbing in and starting it. The sound of the engine was huge and loud.

They left the garage door open. “The heater,” was all she said. In ten minutes they were past the airport and on the Seward Highway, already beyond the city lights. Sandy slumped against her door. Out the windshield the stars were so many and so white they looked like chips of ice, hammered through the fabric of the sky.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/anthony-doerr/about-grace/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Anthony Doerr

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 232.09 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: About Grace is the brilliant debut novel from Anthony Doerr, author of Pulitzer Prize-winning All The Light We Cannot See.Growing up in Alaska, young David Winkler is crippled by his dreams. At nine, he dreams a man is decapitated by a passing truck on the path outside his family’s home. The next day, unable to prevent it, he witnesses an exact replay of his dream in real life. The premonitions keep coming, unstoppably. He sleepwalks during them, bringing catastrophe into his reach.Then, as unstoppable as a vision, he falls in love, at the supermarket (exactly as he already dreamed) with Sandy. They flee south, landing in Ohio, where their daughter Grace is born. And then the visions of Grace’s death begin for Winkler, as their waterside home is inundated. Plagued by the same horrific images of Grace drowning, when the floods come, he cannot face his destiny and flees.He beaches on a remote Caribbean island, where he works as a handyman, chipping away at his doubts and hopes, never knowing whether Grace survived the flood or met the doom he foretold. After two decades, he musters the strength to find out…