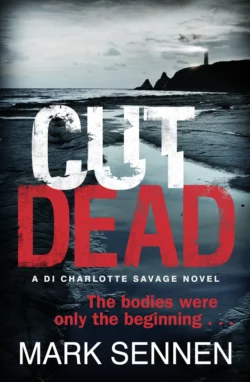

CUT DEAD: A DI Charlotte Savage Novel

Mark Sennen

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Триллеры

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 232.52 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘He could be out there right now. Passing you on the street. You’d never know …’DI Charlotte Savage is back, chasing a killer who was last at large ten years ago, a killer they presumed dead …Now he’s back and more dangerous than ever.When three headless bodies are found mutilated in a pit, it’s a particularly challenging case for DI Savage and her team. The victims bear the hallmarks of a killer who butchered girls to their death; a killer who was never caught.Could this be a copycat or has the original murderer resurfaced? With a steady stream of bodies arriving at the morgue and gruesome secrets from the past emerging DI Savage is up against it to find the killer before he strikes again?Part thriller, part police procedural, a must-read for fans of Mark Billingham and Tim Weaver.