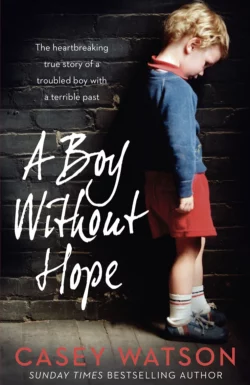

A Boy Without Hope

Casey Watson

A BOY WITHOUT HOPE is the heart-breaking story of a boy who didn’t know the meaning of love. A history of abuse and neglect has left Miller destined for life’s scrap heap. But in this turbulent story of conflict and struggle, Casey Watson is determined to help Miller overcome his demons, show him love and give him hope.Casey Watson is back, doing the job she does best – rolling up her sleeves and fostering the children who, on first meeting, seem like hopeless cases. But when she meets Miller and discovers the truth about his disturbing childhood, even Casey begins to doubt if this child will ever be able to accept love.Found naked and alone on a railway track, Miller was just five when he was first admitted into the care system. Emotionally tormented by his biological parents, Miller has never understood how to establish meaningful relationships, and his destructive past, and over 20 failed placements, is sealing his fate in society’s social scrap heap.After a torrent of violent behaviour and numerous failed attempts to help Miller, Casey decides to make an intervention, implementing a severe regime that strips Miller of all control. But soon the emotional demands of Miller’s case start to take their toll on Casey and Mike. Just how far is Casey willing to go to help Miller and save him from his inner demons?

Copyright (#u6dcccb14-42e2-5a8b-93a4-a0734658d271)

This is a work of non-fiction based on the author’s experiences. In order to protect privacy, names, identifying characteristics, dialogue and details have been changed or reconstructed.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2018

FIRST EDITION

© Casey Watson 2018

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Cover image © Jim Powell/Alamy Stock Photo (posed by model)

Cover layout © HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Casey Watson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008298555

Ebook Edition © November 2018 ISBN: 9780008298593

Version 2018-09-19

Contents

Cover (#u2cb21946-e7f1-5c07-a65f-aba4ef71f263)

Title Page (#u2c9708ac-fb34-5abc-aa8f-066c96697e1d)

Copyright (#u8de97ae1-cb3d-5408-8fc4-2c82cbfcdfe1)

Dedication (#u69032607-9014-55f1-972d-c706b5c48dd3)

Acknowledgements (#u571ddac9-533e-5591-bfbb-32df112c47bc)

Chapter 1 (#ucff8d9d6-fd40-5866-846a-512c54c51d38)

Chapter 2 (#u577404cd-fa97-5c78-a3f2-56701f31dc97)

Chapter 3 (#ub9a91b18-fdd6-5170-9ea9-8031b8bc216d)

Chapter 4 (#u5bd40fb2-4ea3-5ce2-8653-25d6612778f0)

Chapter 5 (#u80037b6d-343f-5595-bfe5-749b7ae097f0)

Chapter 6 (#uab38ae90-2d44-5041-876c-619e24cce9f4)

Chapter 7 (#u063e10d7-d268-5a55-a1a5-01426cb771dc)

Chapter 8 (#ueff07c4b-9851-54a2-abc7-edb9a379f6f8)

Chapter 9 (#ua81ba5af-5738-5dcf-9b37-cd258bffdaf7)

Chapter 10 (#uf0c4b7f1-227e-58ed-be33-298378cd0289)

Chapter 11 (#u5040796b-3691-5a63-ae4d-75207198e941)

Chapter 12 (#u6cb40b7d-90de-5d82-9fa4-ce511b412885)

Chapter 13 (#ua5583a32-50f6-5e05-898c-1273867bdb88)

Chapter 14 (#u1286cda4-0fb1-5957-87c0-f41ee7dc2e4c)

Chapter 15 (#u610a0a65-9b1a-54e0-b7ef-c00dea508ab9)

Chapter 16 (#ubf13742a-1017-513f-a641-7eb2bab23748)

Chapter 17 (#uddf611fc-a3d3-5e88-93f9-f5bf07fce4c3)

Chapter 18 (#u9dc15e80-053d-5c62-9daf-62103109d252)

Chapter 19 (#u54a0f5e5-00e2-5c9f-aab6-28a9485693fd)

Chapter 20 (#u9ce3c168-b6f6-54f9-825d-fbade7bef543)

Chapter 21 (#ud2e1d4ff-822e-56f6-86b7-43616a1da762)

Chapter 22 (#u2e9ba1ee-dafd-5d2f-a6ee-1d3f62d6e16c)

Chapter 23 (#u0adfbabf-6083-5b15-ae9a-b0c321ab1c97)

Chapter 24 (#u2c65d1d9-d5d7-5366-bd56-b9f7563609d8)

Epilogue (#u10c50ee3-e807-5421-b24b-7ccf5901661c)

Also by the Same Author (#uabd7f3c5-dbf6-5565-a364-1d2e6fa56ad0)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#u0419382c-c106-5f79-a401-2e38d0af8277)

About the Publisher (#ufdfc1ba0-bf30-5334-b9c0-400b12628855)

This book is dedicated to the army of passionate foster carers out there, each doing their bit to ensure that our children are kept as safe as possible in such a changing and often scary world. As technology is reinvented and becomes ever more complicated for those of us who were not brought up amid such advances, we can only try to keep up, in the hope that we continue to learn alongside our young people.

Acknowledgements (#u6dcccb14-42e2-5a8b-93a4-a0734658d271)

I remain endlessly grateful to my team at HarperCollins for their continuing support, and I’m especially excited to see the return of my editor, the very lovely Vicky Eribo, and look forward to sharing my new stories with her. As always, nothing would be possible without my wonderful agent, Andrew Lownie, the very best agent in the world in my opinion, and my grateful thanks also to the lovely Lynne, my friend and mentor forever.

Chapter 1 (#u6dcccb14-42e2-5a8b-93a4-a0734658d271)

Some things are set in stone. That’s as true for me as for anyone. Those little anchor points of life that provide stability and reassurance. The perfect way to make coffee. Tyler’s special breakfast porridge. The fact that Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without at least a dozen strings of fairy lights. Mike’s bear hugs. My many cleaning routines.

Birthdays, too, of course. Not to mention all the associated parties. Particularly those of my grandkids, in which my role was unchanging: chief entertainment officer, chief caterer and, invariably, chief bouncer as well.

I held two hot, sticky hands in mine – those of my two darling granddaughters, whom I was about to lead, suitably subdued, back into the dining room.

‘Now, girls,’ I said in my strictest grandmother voice, ‘are you sure you can go back into the party without arguing?’

Marley Mae, my daughter Riley’s youngest, opened her mouth in indignation. She was never one to shy away from giving the world the benefit of her opinion, but clearly thought better of it having caught my expression. So instead she sighed heavily, as if having been forced to concede a great military defeat.

‘Well?’ I asked.

‘Yes, Nan,’ she said finally, reaching around to wrap her cousin in a bear hug and mumbling the requisite ‘sorry’ as she did so.

My son Kieron’s daughter Dee Dee, now three, was a year younger than her bossier cousin, and though they loved one another, they were both very competitive, so managed to find an argument in just about anything. Today’s anything was a pink balloon, which both had laid claim to, and, in the ensuing scuffle, it was a miracle it hadn’t already popped. Perhaps better that it had, to stop them squabbling over it. As it was, I had tethered it to the bannisters instead, telling them that if they couldn’t share nicely then neither of them could have it. ‘And I don’t want to hear any more about it,’ I told them sternly. ‘This is Jackson’s birthday party. Which means it’s his special day. So no more of this arguing. You both got that?’

They both duly nodded, keen to rejoin the party. So I opened the door and ushered them back into the dining room, where a game of musical bumps had just started.

‘You should have left both of them on the naughty step, Mum,’ Riley said as I rejoined her in the kitchen area. ‘Marley Mae gets four minutes at home when she carries on like that. She needs to learn to share better.’

‘Oh, she will,’ I told my daughter. ‘School will sort her out in no time. It’s only because she has two older brothers who give into her all the time because they want a quiet life.’

‘Maybe,’ she said, though she sounded unconvinced. ‘I wish she could go full-time. She’s more than ready. And so am I! September seems a very long way away still.’

‘Problems?’ Kieron asked, as he passed me his empty coffee mug. ‘Well, they all look as if they’re having fun. I can’t believe Jackson is ten already. Can you?’

Kieron has Asperger’s, which is a mild form of autism, and one of his special talents is asking questions, making statements and issuing instructions all at once. It’s been the same since he was little; as if he makes these mental lists of every passing thought, before opening his mouth.

‘No problems we can’t handle,’ I told him. ‘And yes, they are having fun. And, yes, time flies – I can’t believe Jackson is ten already either. And yes, I’ll make more coffee. Anything else?’ I added, laughing at his confused expression.

‘Oh, yes,’ he said, handing me my mobile, which I hadn’t spotted. ‘Here you go. John Fulshaw’s on the phone.’

‘Oh Kieron, honestly,’ I said, snatching it from him. ‘You could have started with that, couldn’t you? Sorry, John,’ I added, as I put the phone to my ear. ‘As you probably noticed, you’ve caught me mid-party. Hang on, let me find somewhere quieter to talk.’

I wove a path through a dining room full of small people, and some unfamiliar adults, into the conservatory, en route to the back garden – the one place, because of a heavy April shower earlier, we had opted to make out of bounds. I’d happily agreed to Riley’s suggestion that we hold Jackson’s party at our house – it was a good bit bigger, so it made sense – but I’d forgotten just how many friends the average ten-year-old simply must invite to their parties. These days, a whole form’s worth, plus a couple of extras, seemed to be the norm. Throw in a couple of cousins, and friends from various clubs and activities, plus half their parents (did they not have anything better to do?), and there didn’t seem an inch of our downstairs that wasn’t occupied by a human, and the house seemed to be creaking under the strain of it all.

Literally, I thought, as I clacked across the squeaking floorboards.

‘You sound a bit ruffled, Casey,’ John said, once I’d shut both the door and noise behind me. ‘I could always call back later if you’d rather?’

‘No, no,’ I said, perching myself on an upturned log at the bottom of the garden. ‘It’s just a birthday bash for one of the grandkids, and it’s a good excuse to escape for a few minutes, to be honest. I think I’m getting a little old for all this mayhem. But nothing that won’t be over within the next hour or so. Anyway, long time no speak. To what do I owe the pleasure? Have you got a child for us?’

In reality, it had been no more than three weeks or so, but John, being our fostering link worker, was so much a part of the regular fabric of our lives that three weeks was actually quite a while. We’d been in limbo for the last three months or so – ‘recuperating’, for want of a better word, after our last long-term child had left us.

Though Keeley hadn’t been a child, quite. She’d turned sixteen while she was with us. And had taken us down some intense, uncharted waters. Since then, Mike and I had quite enjoyed being on the back burner. We’d been doing respite work – where you step in short term to support other full-time foster carers – a few days here, a week there, nothing too challenging. And though we had experienced the odd trauma (one weekend visitor, for instance, was so fond of absconding that she arrived complete with a tracking bracelet on her ankle, and decided to abscond anyway), these were short bursts of fostering activity in a largely calm, family-orientated landscape, for a change. And with four grandchildren now, I was kept pretty busy as it was.

I never thought I’d say it, but I wasn’t feeling the usual tug that always used to happen when I didn’t have a child in. And I also had Tyler, our permanent foster son, to think about. He had GCSEs coming up in a few weeks now, and we wanted to support him as well as we could.

‘Actually, no,’ John said, surprising me. ‘It’s news of a slightly different kind. News I wanted to share with you and Mike before it becomes public knowledge. So I was wondering if I could pop round for half an hour in the next day or so.’

‘What kind of news?’ I demanded.

He chuckled. ‘I’d rather tell you face-to-face.’

‘Oh, don’t go all coy on me, John. What?’

‘When are you free?’

‘Oh, for goodness’ sake,’ I said. ‘But okay, you win. This evening?’ I looked at my watch. ‘Mike will be home within the hour – on pain of death, I might add – and we should have cleared everyone out soon after. Why don’t you come over around seven? Assuming you’re in the office, that is?’ John was famous for never leaving work much before that.

‘Perfect,’ he said. ‘Now I’ll let you get back to the party.’

His tone was bright and chirpy, so why did I fear bad news so much?

***

‘Because it will be?’ Mike said, as he shovelled the last of the paper plates into the recycling.

He had narrowly avoided being hung, drawn and quartered by showing up a full twenty minutes before the designated end time and entertaining the kids with some high-octane rough and tumble, while Riley and I divvied up the birthday cake and wrapped sticky slices to shove into the thirty-five-odd party bags. Yes, they’d leave hitting the ceiling with over-excitement, but once they’d calmed down they would all sleep well tonight.

Now it was just a case of sluicing down and tidying up. ‘He didn’t sound as if it was,’ I said. ‘But my antennae are twitching.’

‘And definitely not a new child?’ Mike asked.

‘He said not. Though there’s a thought. Perhaps an old one?’

This did happen sometimes; you thought a child had moved on from you successfully, only to have things break down – perhaps at home, or with a ‘forever’ foster family – months or even years down the line. It hadn’t happened to us, but that wasn’t to say it couldn’t.

‘Well, there’s no point in speculating,’ Mike said, as he knotted the green bag. ‘It will be what it will be. And he’ll be here any minute to put you out of your misery. In fact …’ We heard the bing-bong of the doorbell simultaneously. ‘Speak of the devil. Get the kettle on. I’ll go and let him in.’

Mike did so, and moments later John was standing in my kitchen in his ‘lucky’ jacket. A raggy tweed number, which couldn’t have screamed ‘public sector’ louder, and which he’d had for as long as I’d known him. For all his teasing earlier, he shrugged it off and came straight to the point. ‘I’m leaving,’ he said. ‘End of this month.’

‘Whaaaatttt?’ I said, teaspoon of coffee in mid-scoop. ‘As in leaving? As in two weeks from now? Just like that?’ I knew my face was probably reflecting my emotions a little too much, but I couldn’t help it. How could this be happening so suddenly, and so soon?

Or, more accurately, why didn’t I already know? Jobs like John’s weren’t the kind that you just walked away from with a couple of weeks’ notice. They had long notice periods, and complex, structured handovers. John was the fostering agency as far as I was concerned. He knew everything and everyone; how could it possibly cope without him? Yes, a bit melodramatic, maybe, but not too far from the honest truth.

‘I know it’s a bit out of the blue,’ he said, ‘and it’s not how I’d planned it. It’s just that my dad’s not well, as you know, and we really need to relocate, and –’

‘Oh, God, John, I’m sorry,’ I said, feeling awful. I knew his dad had been ill. I knew he lived alone, some way distant. ‘I didn’t mean it like that. Of course, you must. Just ignore me. Sorry – but, God, it’s just so sudden.’

‘So leaving the service entirely?’ Mike asked, pulling out a chair and gesturing that John should sit on it. ‘Quite a big life change for you, then.’

‘Yes and no,’ John said. ‘And, Casey, really, don’t worry. I’m not dashing off to attend him on his death bed or anything. He’s getting a kidney transplant and all being well it’s going to revolutionise his life, so it’s all positive. And the truth is that I’ve been offered this promotion twice already and have always said I’m not interested – not least because we’re so settled here. But with Dad and that, well, it seemed fate was telling me something, and as there’s someone unexpectedly available who can slot in pretty easily …’

Promotion. Of course. Why wouldn’t he want promotion?

‘So what’s the new job?’ I asked, recovering my equilibrium a little.

‘I’m taking over as Senior County Manager. You know, mixing with all the big wigs and overseeing some of the regional teams.’

‘So just leaving the area,’ Mike said.

John nodded. I put his coffee in front of him. ‘And they already have a replacement for you?’ I asked. ‘How can they? You’re irreplaceable. Everyone knows that.’

John grinned. ‘Thanks for the vote of confidence, Casey. That’s so nice of you to say. But it’s still absolutely not true. That’s why we’re able to rush things through. I know it sounds as though I’m deserting a sinking ship, what with all the budget cuts, and politics, and extra stress everyone’s been facing just lately, but I’m hoping I’m going be in a position of greater influence.’ He grinned. ‘Speaking truth to power, and lots of other noble stuff like that.’

‘Well, congratulations,’ Mike said, raising his own coffee mug. ‘Good on you. Lovely as it’s been to have you all to ourselves for so long, if the call comes, why wouldn’t you take it? Cometh the hour, cometh the man and all that. The state that social services are in these days, we need some sort of shake-up. Casey, we will cope,’ he added, seeing my ill-concealed stricken face.

‘Thanks, Mike,’ John said. ‘I have to say I’m really looking forward to it. It’s going to be very different – not to mention very challenging, I don’t doubt – but I’m not going to miss working the ridiculous hours I do. And neither will ’er indoors, as I’m sure you can imagine. Well …’ He smiled. ‘You two, of all people, know all about that, don’t you?’

Didn’t we just. And we’d never minded. It was the nature of what we did. But to do it without John? Calm, capable, unflappable, always-at-the-end-of-the-phone, supportive, lovely John? I simply couldn’t imagine it.

‘I’m really, really pleased for you,’ I told him, and, despite my shock, I meant it. It was because he had always been all of those things that he needed, and deserved, to have a break from it. We all knew the saying that on your death bed you never wish you’d spent more time at the office. But how many of us forget it till it’s all too late? This was absolutely his time to remember and act on it. And there was no doubt about it. He should.

‘Thanks, Casey,’ he said. ‘I knew you would understand. I was worried about a general foster-carer exodus – I still am – but I knew I could rely on you two. Change is always hard, but I’m sure you’ll get on brilliantly with Christine Bolton once you get to know her, and –’

‘Christine? So it’s a woman taking over from you?’ I asked him. ‘The name doesn’t ring a bell. Should it?’

‘No,’ John said, ‘she’s not from round here. She’s relocating too. She’s currently based in Liverpool. Doing pretty much the same job as me. And the reason it’s all fallen into place the way it has is that she wants to move fairly quickly for family reasons, too. I don’t know all the details, but I believe her partner needs to return here. Another elderly parent situation.’

‘Twas ever thus …’ mused Mike.

But I had fixed on something else. ‘Once we get to know her?’ I asked John, whom I knew better than perhaps he realised. ‘Why “once you get to know her”? Come on. What aren’t you telling us?’

He looked slightly uncomfortable. ‘I shouldn’t have put it like that. She’s really nice. And very professional.’

‘But?’ I was like a dog with a bone now.

‘There aren’t any buts,’ he said. ‘Honestly, Casey. I’ve already met up with her a couple of times, and we’re obviously liaising closely re the handover and everything. Seriously. Don’t look like that. She’s fine. I just meant – well, you know how it is – different people have different ways of doing things, don’t they? That’s all I meant. That everyone will have to adjust to everyone’s different … um … peccadillos. That goes with the territory when you’re part of a multidisciplinary team, and –’

‘Blinding me with science now – I get it. Come on, spill, John Fulshaw. Is she an overbearing battle-axe? If so, we need to know.’ I pushed up the sleeves of my top. ‘Forewarned is forearmed, and I need some ammo.’

John burst out laughing. ‘Oh, God,’ he said, winking at Mike once he’d recovered his composure. ‘I am so going to miss this one! I’m going to miss all of you,’ he added, more seriously. ‘D’you know, I was thinking on the way here – it’s been so many years, hasn’t it? So many children. And your two all grown up – and both now with their own kids. Your grandkids. How is that even possible? And Tyler sixteen now. How did that happen?’

Tyler had come to us as an eleven-year-old, with a terrible, tragic background: a dead heroin-addict mother, a father who didn’t want him, and, after all sorts of heart-breaking emotional abuse, he’d ended up going for his step-mother with a kitchen knife. I still remembered the day I’d gone to fetch him from the local police station, immediately afterwards. Hard not to, given that, during that first memorable meeting, he’d spat at a police officer, kicked a chair around the interview room, called his stepmother a witch, called another officer a ‘dick brain’ and, for good measure – he was obviously keen to make a good impression – told his social worker to fuck off. Though I didn’t know it as that then – I’d been tickled by him more than anything – what I’d actually felt had been love at first sight.

‘He’s going to miss you,’ I told John.

‘I’m going to miss him too – a lot. All of you. And’ – he chuckled again – ‘how many house moves has it been now? It really does feel like the end of an era, doesn’t it?’

‘Oh, God,’ I said, reaching for the kitchen roll. ‘Don’t set me off.’

But, of course, he already had.

***

Change. Change is good. Change is necessary even. And, as a resilient foster carer, one might imagine it was something I coped with brilliantly. And, in the main, for most of the time, one would have imagined right, because I did. Especially given that on the surface, our household never had a routine, not in the conventional sense.

But, deep inside, I knew I shared some of the traits of my Asperger’s son. Yes, I could cope with chaos easily, but only as long as certain things were set in stone. It wasn’t necessarily visible, because my real routine simply hummed away in the background. The forefront of my life could be as messed up as it liked, as long as some things never changed; as long as what really mattered was set in stone.

Now one of those things, those reassuring rocks, had begun to crumble, and I wasn’t sure this change was going to be one that I could easily cope with. Wasn’t sure, given everything, if I even wanted to try.

Plus John still hadn’t answered my question.

Chapter 2 (#u6dcccb14-42e2-5a8b-93a4-a0734658d271)

Because time was short, and he had a lot to tie up before leaving us, we had two days to reflect on John’s bombshell. Which wasn’t really that much of a bombshell – why on earth wouldn’t he get promoted? – but since I’d obviously had my head stuffed deep into the sand, it still took a fair bit of getting used to.

Mostly I chuntered on, uncharacteristically negative, unable to do the one thing Mike deemed to be the only thing – to stop wondering what John’s replacement was like and simply wait and see. But we both knew there was actually a bit more to it than that, because it wasn’t just a case of whether we bonded with her or didn’t – it was also the timing, coming along at precisely the point when I was seriously considering a change in direction myself. Was this the catalyst that would make me jump one way or the other? It certainly felt like fate had arranged it that way.

I was also nervous, those words ‘very professional’ running round and round my brain. I had visions of a sharp-suited, shoulder-padded dynamo – the sort of vision of a high-flying, glass-ceiling-smashing career woman that many of us can so easily call to mind. Which was ridiculous. She might equally be gentle and mumsy. Being professional isn’t about the clothes you choose to wear, particularly when you’re in the line of work we were, dealing with messy domestic dramas and troubled, angry children, sometimes in the small hours, having tumbled blearily out of bed. John had certainly done his share of that and it was odds-on that this Christine Bolton would have too.

But, having worked myself up, I still felt a bit intimidated, so much so that on the day itself I had ants in my pants. Big soldier ants, with big pincers, trying to chew me up. Which was probably why I was so irritable.

‘Come on,’ I snapped at Tyler, who was wading through his cereal on slo-mo. ‘You’re going to be late if you don’t hurry up.’ I pointed at the kitchen clock. ‘Look at the time! The bus’ll be here in two minutes, and you don’t even have your shoes on. Arrgh!’

Being the bright teenager that he was, Tyler had obviously seen this coming. He looked straight past me at Mike, who was leaning against the kitchen counter, reading the paper while waiting for the kettle to boil. He’d had some changes of his own, in his job managing a warehouse, having reached a height lofty enough to delegate some of his duties, one being the relentless ridiculously early starts. For a couple of days a week now, he was still at home at breakfast time.

Which was presumably why they always seemed to be in cahoots these days. ‘See, Dad,’ Tyler said, ‘I told you she’d be like this, didn’t I? It’s alright though,’ he added, reaching for the offending trainers. ‘My shoulders are broad. Calm down, Mum,’ he said, smiling at me as he leaned down to put them on. ‘The woman will be just fine, everything is sparkly clean, and she won’t fail to be impressed that you’ve got the bone china out.’

I swiped him with the tea towel. ‘Bone china? As if!’ I huffed. ‘She’s lucky she’s not drinking cheap coffee out of a mug, and for your information, young man, I am calm. Now hurry up and get yourself sorted rather than nit-picking at me.’

I saw the exchange of raised eyebrows between my husband and foster son and was at least able to manage a bit of a grin myself. They were right, of course. Considering how many years I’d been fostering and the amount of social workers I had met, it made no sense that I was getting so strung up about meeting Christine Bolton. After all, she was simply an agency link worker, like John was, or, at least, used to be, and hadn’t he said that she’d moved over from Liverpool? Yes, he had. So she probably wouldn’t have that clipped, cut-glass accent that usually made me feel so nervous. It was ridiculous of me to get myself in such a state. So why was I?

‘Don’t worry, Casey,’ Mike said after Tyler had at last set off for his bus. ‘Remember what I said? If you decide it’s time to hang up your fostering apron, then so be it. That’s completely fine. After all, it’s you who has all the day-to-day stuff to contend with. If you’ve had enough, you’ve had enough and I’ll support you whatever you decide.’

We had talked long into the night after John’s news about this and I think it was the first time I had ever voiced the notion and actually meant it. I’d even drifted off to sleep thinking that I’d phone my sister, Donna, and ask her if she could guarantee me a few shifts at her tea rooms, Truly Scrumptious. One thing I really lacked these days, especially with my own kids long flown, was the ridiculously simple pleasure of daily adult company. Perhaps it was time to put that right.

I stared into my posh china cup, which I hated. Truth was, I didn’t know what to do. On the one hand, I loved my job. I loved most of the children that entered our lives, and felt privileged to be able to play a small part in helping them towards a better future. On the other hand, I recognised that I often felt tired and disillusioned with all the red tape.

Because fostering had changed over the years. That was a fact. Financial cuts meant that social workers these days often barely knew the kids they were responsible for. They might have as many as twenty children on their caseloads and just didn’t have the time to build a meaningful relationship with them, so the all-important trust just didn’t seem to be there. Statutory visits, meant to take place at least every six weeks, often got cancelled at the last minute, which compounded it. As a consequence, relationships, period, just weren’t the same any more. It deeply bothered me that it seemed to be all about counting the pennies out, and less about the actual children.

‘I’m still not sure, love,’ I told Mike. ‘I think it might depend on how settled I feel when we meet this new woman. I mean, we’ve been so lucky to have had John for so many years, and that he felt the same as we do. I’m just hoping she’s of a similar mindset, that’s all.’

‘And if she isn’t?’ Mike asked

‘Well, we’ll just have to see,’ I said. And I meant it. ‘I know I’m impulsive. I know I sometimes act first and think later. But I really will put a lot of thought into it before deciding.’

‘Well, that’ll be a first,’ he said. ‘But you know what? I don’t think you’ll need to. This is one of those times where I think your instinct will – and should – lead the way. Hey,’ he added, reaching for the matches so he could light the scented candle I’d dug out. ‘Maybe she’ll be a tea drinker! Then you won’t have to think at all, will you?’

Which comment made it all but impossible for me not to explode into nervous laughter, when, ten minutes later, our new visitor responded to my usual opening gambit of ‘Drink? Tea or coffee?’ with ‘Oh, tea for me, please – every time.’

I might have done, too, had John not beaten me to it, along with a jaunty ‘Forgot to tell you, Casey – Christine hails from the dark side.’

Though in truth, a tea drinker was exactly what she looked like. Which, bizarrely, given my prejudices, was something of a comfort. Yes, she was dressed in a sharp skirt and jacket suit, and there was no denying that she looked ready for business, with her fair hair perfectly blowdried and her big leather laptop case, and the label – Ms C. Bolton – on a folder she’d pulled out, but there was at least something approachable about her that I hadn’t anticipated, enhanced by her soft Liverpudlian accent, and her readiness to accept a chocolate chip cookie, which she dunked in her tea while John went through his spiel. You couldn’t mistrust a dunker, could you?

Having never been through a change-over of fostering link worker before, I had no idea how these things usually went. Though I didn’t doubt there would be a protocol – there was a protocol for everything. But it turned out there wasn’t – not in my house, at any rate. Such official handing over of responsibilities as needed to happen had already happened. And would continue to do so, John explained, over the next couple of weeks, during which time Christine would shadow him in his various duties.

And this was one such – no more than an unofficial ‘meet and greet’, really. One where I had the bizarre notion that the poor woman was having to repeat herself endlessly, in a series of thinly veiled ‘pitches’ to John’s stable of carers, as if she was on The Apprentice or something, having to go from house to house, laying out her credentials over endless cups of tea. I wondered how far along the line we were. She certainly seemed to have memorised her script.

‘John speaks very highly of you both,’ she said as she daintily sipped her tea. ‘So I’m very much looking forward to us working together. I’m also hoping that both of you might be something of a crutch for me, while I’m finding my way around the way things work here. All those boring procedures and so on.’

I laughed politely. ‘Likewise,’ I told her. ‘But I’m sure John’s also told you I’m a bit of a scatterbrain, so I doubt I’d be much use as a crutch. In fact, if I’m honest,’ I rattled on, ‘I’m usually the one who’s battling against procedure’ – I grinned at John – ‘more often than the other way around.’

John spluttered slightly. ‘That’s not true at all, Christine,’ he said. ‘Yes, Casey does sail a little close to the wind at times, as I’m sure she’ll be the first to admit. But as I explained on the way here’ – he grinned back at me – ‘that’s only because she cares. She’s fiercely protective of the children she looks after for us, and will fight tooth and nail to be their advocate if she feels there’s any injustice. But that’s one of her great strengths. Am I right, Mike?’

Mike nodded. I blushed, feeling Christine’s eyes on me. Feeling scrutinised. I wondered what else they’d already discussed. ‘And I’m sure you’ll soon get the hang of things, Christine,’ Mike said. ‘And you’ll love working over this end. We’re not a bad bunch round here. What about your own family? How are they finding the relocation?’

‘No family. Just myself and my husband Charles,’ she answered. ‘He’s an accountant, and he does a lot of work from home, which makes it easier. Which it needs to be, given how erratic my hours can be, of course.’

She smiled. I smiled back. So it looked like they were childless. Which didn’t make any difference. It shouldn’t, and it wouldn’t. Some of the most remarkable advocates for and defenders of children were able to be so precisely because they didn’t have their own. I judged her to be in her mid-forties or thereabouts. I wondered if it was a case of not wanted, not yet, or not able. Then checked myself – these were thoughts that wouldn’t have even occurred to me had a man been sitting across from me – and that was food for thought in itself. But perhaps being female made it difficult not to have them. As a person blessed (or cursed) with a strong maternal urge, I was always interested in women’s choices, and how they made them. Or, in the case of so many of the kids we had fostered, how those choices were taken away from them. I wondered what had brought Christine Bolton into the world of care and children.

It sounded as if she had other things to worry about, however. ‘The main thing is that we’re closer to my husband’s parents,’ she said. ‘He’s an only child and his father has Alzheimer’s,’ she explained. ‘Being closer means he’ll be able to help his mum out a lot more. You probably know what it’s like.’ We all nodded, in unison. Was there a family around not impacted by dementia? I counted my blessings that my own parents, both now in their late seventies, had so far been spared.

‘That must be tough,’ I said. ‘But, as you say, being closer will make things easier. And here’s hoping you’ll have the space to ease into work gently, so you can get yourself orientated and settled in.’

At which point John coughed. And Christine Bolton looked across at him. I’m no Sherlock Holmes, but I clocked it immediately. I caught his eye.

‘So,’ he said, ‘does anyone have any questions?’

Only one unspoken one, I thought. What’s going on? I looked across at Mike, who was rising from his chair, ready to say his goodbyes and head for work. And I could tell he was wondering that too. And when John retrieved his case from where he’d parked it under the table, Mike sat down again. ‘I have,’ he said to John. ‘And it’s “And?”’

John had the grace to look guilty. Though, actually, not that guilty. Because, given that he was leaving, why would he? He pulled a manila file, smooth as silk, from his trusty bag.

He looked at me. ‘You don’t have to say yes, Casey,’ he said as he held it up. ‘And I’m not playing games with you, I promise,’ he added, having read my expression (something he was obviously good at) and correctly interpreting it as one of irritation that what he’d been doing was exactly that.

‘A child,’ Mike said, nodding towards the unopened file.

‘A twelve-year-old boy,’ John said. ‘Name of Miller Green. And this literally landed on my desk only this morning, or of course I’d have phoned you and told you both. We’ve barely even had a chance to have a read through of all the notes, have we?’ he added, glancing at his now professionally grim-faced successor. ‘And I obviously didn’t want to welly straight on into it till you and Christine had had a chance to get acquainted. So …’

‘Sounds fair enough,’ Mike said mildly. ‘What’s the story?’

‘First thing is that this doesn’t sound like an easy one,’ John admitted. ‘So you’ll have to think hard before agreeing to it, okay? And I mean that.’ He tapped the file. ‘This looks like one challenging kid.’

At which point I’d have normally thought bring it on. I didn’t. ‘So?’ I asked instead. ‘What’s his background?’

John donned his reading glasses and skimmed through what he’d obviously identified at the key facts. ‘A really sad case, it seems. Poor kid was first known to social services when he was found playing on a railway crossing, adjacent to a busy road, almost seven years ago. Almost naked, etc., etc., police called to investigate, parents didn’t want him – they’re both long-term substance abusers, apparently. The boy’s been in care ever since. But a huge number of placement breakdowns. And I mean huge. From what I can gather, there’s also a pattern. Always seems to feel the need to destroy it almost before it starts.’ John glanced at me from over his glasses. ‘Frequently described as being “difficult to like”.’

He’d freighted the last three words with heavy, deliberate meaning. ‘And where is he now?’ I asked.

‘Currently with a foster couple called Jenny and Martin in another county,’ John said. ‘Martin works away during the week, and Jenny can no longer cope. The boy has been excluded from – it says here – “yet another school, and is not at the moment in education”. Jenny wants him gone as soon as possible. Ideally today.’

’Wow!’ I said. ‘I know you’re not trying to put me on the spot, but this really is a decision that needs making, like, now, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, it does,’ John admitted. ‘Though, given what we do know about the boy, and his previous history, plus the fact that he’s currently out of education, we don’t expect you to make a long-term commitment right away. All we’re after is a commitment to giving it a proper shot. See how things go, say, for starters, on a month-by-month basis. Well supported, of course. You know you can depend on that.’

A proper shot, I thought. As if we’d ever commit to anything less! But well supported? Without John? And by this brisk, slightly stiff woman?

‘Well, of course,’ I said. ‘Obviously. But –’

Then Christine jumped in. ‘But we completely understand if you think it might be too big an ask for you. I mean given his age – and let’s face it, none of us are getting any younger, are we? Please feel free to say no, and we can keep the door open for you to take on a child who doesn’t come accompanied with quite so many challenges.’

I stared at John in disbelief. In fact, I think my mouth hung open for a good twenty seconds. Too big an ask? None of us were getting any younger? Take on a child without quite so many challenges? Cheeky mare!

A part of me accepted that she was just covering the bases. If she sensed any hesitation, it was right that she did, too. It would be insane to place a child with carers any less than 100 per cent willing. Placement breakdowns were damaging. And it seemed this kid had already suffered quite a few.

But, whether she was aware of it or otherwise, her words had hit a nerve. Needless to say, if there was one thing I always rose to, it was a challenge. In this case, the challenge of correcting Ms Bolton in the matter of the impression she had obviously already formed about me. So it was that I opened my mouth before engaging my brain. ‘We’ll do it,’ I said firmly. ‘He sounds right up my street.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/casey-watson/a-boy-without-hope/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Casey Watson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Социология

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A BOY WITHOUT HOPE is the heart-breaking story of a boy who didn’t know the meaning of love. A history of abuse and neglect has left Miller destined for life’s scrap heap. But in this turbulent story of conflict and struggle, Casey Watson is determined to help Miller overcome his demons, show him love and give him hope.Casey Watson is back, doing the job she does best – rolling up her sleeves and fostering the children who, on first meeting, seem like hopeless cases. But when she meets Miller and discovers the truth about his disturbing childhood, even Casey begins to doubt if this child will ever be able to accept love.Found naked and alone on a railway track, Miller was just five when he was first admitted into the care system. Emotionally tormented by his biological parents, Miller has never understood how to establish meaningful relationships, and his destructive past, and over 20 failed placements, is sealing his fate in society’s social scrap heap.After a torrent of violent behaviour and numerous failed attempts to help Miller, Casey decides to make an intervention, implementing a severe regime that strips Miller of all control. But soon the emotional demands of Miller’s case start to take their toll on Casey and Mike. Just how far is Casey willing to go to help Miller and save him from his inner demons?