Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Len Deighton

Epic prelude to the classic spy trilogy, GAME, SET and MATCH, that follows the fortunes of a German dynasty during two world wars.Winter takes us into a large and complex family drama, into the lives of two German brothers - both born close upon the turn of the century, both so caught up in the currents of history that their story is one with the story of their country, from the Kaiser's heyday through Hitler's rise and fall. A novel that rings powerfully true, a rich and remarkable portrait of Germany in the first half of the twentieth century.In his portrait of a Berlin family during the turbulent years of the first half of the century, Len Deighton has created a compelling study of the rise of Nazi Germany.With its meticulous research, rich detail and brilliantly drawn cast of characters, Winter is a superbly realized achievement.

Cover designer’s note

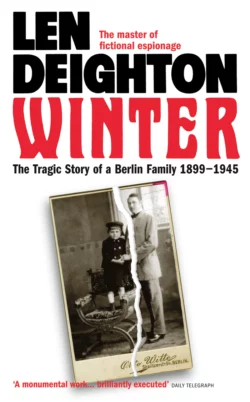

In attempting to come up with a concept for the cover design for Winter, Len Deighton’s saga of a Berlin family set in the first half of the twentieth century, I sought a striking image that would express the outcome of the Winter family’s story. I recalled a photograph in my wife Isolde’s family album of her father as a child dressed in a sailor suit standing beside his father. This image seemed to fit the time and place precisely. By tearing the photograph apart it implied the outcome of their relationship; and in a metaphorical sense it would also suggest what lay ahead for the city, and indeed the entire country. Sometimes the simplest of images are the most effective.

The related ephemera on the back cover includes a number of objects of the period taken from my personal collection, including a gramophone needle tin (which was featured in my book Phonographics) that has the Berlin dealer’s name on the lid; its contents still containing a few needles, a small button and an unused Adolf Hitler postage stamp. Also appearing is a china Zeppelin ornament, several early postcards including one of Graf Zeppelin and one of the Brandenburg gate, plus a German bank note. The group photograph is of my wife’s mother’s family.

The Nazi era stamp on the book’s spine commemorates Graf Zeppelin and his airship LZ2, one of many that did not survive to make a second flight. Fortunately, when she was driven to the ground in 1906 by winds too strong for her engines, no one was hurt. But this was rarely the case.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

Len Deighton

Winter

The Tragic Story of a Berlin Family 1899–1945

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Hutchinson Ltd 1987

WINTER. Copyright © Len Deighton 1987

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2010

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content or written conten in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780586068953

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2010 ISBN: 9780007387212

Version: 2017-08-18

Contents

Cover designer’s note

Title Page (#ue02e7708-09b0-592c-94ef-d455be0d466f)

Copyright

Introduction

Prologue

1899

‘A whole new century’

1900

A plot of land on the Obersalzberg

1906

‘The sort of thing they’re told at school’

1908

‘Conqueror of the air – hurrah!’

1910

The end of Valhalla

1914

War with Russia

1916

‘What kind of dopes are they to keep coming that way?’

1917

‘Not so loud, voices carry in the night’

1918

‘The war is won, isn’t it?’

1922

‘Berlin is so far away and I miss you so much’

1924

‘Who are those dreadful men?’

1925

‘You don’t have to be a mathematician’

1927

‘That’s all they ask in return’

1929

‘There is nothing safer than a zeppelin’

1930

A family Christmas

1932

‘Was that more shouting in the street?’

1933

‘We think something is definitely brewing over there’

1934

‘Gesundheit!’

1936

‘Rinse and spit out’

1937

‘You know what these old cops are like’

1938

‘Being innocent is no defence’

1939

‘Moscow?’ said Pauli

1940

The sound stage

1941

‘It was on the radio’

1942

‘I knew you’d wait’

1943

‘Happy and victorious’

1944

‘We’re all serious’

1945

‘It’s a labour of love’

Keep Reading (#uc70d52ce-a1a1-532f-86f1-2d9e952b80a6)

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Introduction

This is how it started. It was Friday afternoon – exactly 2.20 pm – and the snow was falling. The flakes that hit the car’s windscreen were not the soft, watery sort that slide downwards and fade away like old soldiers. These were solid bullets of ice, perfectly formed and determined to stay put. These were German snowflakes. Our elderly Volvo was on the road heading west from Munich, with the cold waters of the Ammersee close at hand and my sons on the back seat politely starving to death. My wife was at the wheel. ‘The next place we see; we stop,’ I said. ‘It’s getting late. I don’t care if it’s just a currywurst van parked on the roadside.’

The ‘next place’ was the Gasthof Kramerhof. It was a typical Bavarian inn, with a large restaurant that attracted locals and a few well-kept rooms for travellers. It was sited well back from the road and had an extensive parking area, which is often a measure of an inn’s popularity. Now lunchtime had ended and there were no cars there. The loops of tyre tracks that marked their departure were now disappearing under the continuing snowfall. But in such a Gasthof all travellers are welcome and mealtime lasts all day. Soon we were relishing a Bavarian meal: kraftbrühe – clear soup – followed by pork cutlets in a sour cream sauce with spätzle on the same plate. Had I been better informed about German food I might have guessed that the owners were Schwabs, for these were the long square-sided ‘pasta’ that is a delight of Schwabian cooking.

Outside, the snow was conquering the world. The sky was steely grey and descending upon the treetops. Stacked on the Volvo’s oversized roof rack, our bags and boxes now looked like a scale model of the Alps. What else was there to do? We stayed there for the weekend. That’s all it took for the Kramerhof to become our home and we remained there for many months. From the hotel room we moved one floor higher where I set up my portable typewriter in the attic rooms originally furnished for a mother-in-law. It was cramped under the steeply sloping roof and I banged my head a lot but this was the sort of Germany I wanted to write about. All the events of the neighborhood were celebrated there under our noses, from weddings – complete with amateur brass band – to hunting-dinners from which the smell of wine-rich venison drifted upwards to reach us in the early hours of morning.

My wife’s fluent German impressed the lady in the village post office and we soon knew everything about everyone. There was enough social life to furnish a dozen lurid novels. Retired military men abounded. I met a relative of General Gehlen, one of the very few spies who influenced history. The Kramerhof food was wonderful, the customers were entertaining and the owners became friends. They allowed us into the well-ordered kitchen where we learned how to make Schwabian spätzle and much more.

Winter was a biography of the Germany I had come to know over the years. We had lived in Vienna and in an Austrian village near Salzburg, which was now not all that far away, and my sons spoke a strongly accented German. For many Germans, and many historians too, Germany and Austria do not have a separate existence. AJP Taylor, who taught me so much about German history, persuaded me to consider both in unison and for that reason the story of Winter begins in Vienna. One of our neighbours in Riederau village had a son writing for a newspaper in Vienna. At my request, he rummaged through the archives to find out what the weather was like in Vienna on ‘the final evening of the 1800s’. Now I had no excuse for delay.

I knew what I wanted to say; I had been planning it for years. My hesitation had come from the problems of continuity. In the beneficial absence of formal instruction in the skills of writing fiction, I found it natural to write sequences in ‘real time’. In my book conversations and physical actions as depicted were apt to take about the same time as the reader took in reading about them. Of course there were expansions and compressions so that only the highlights of dinner party chit-chat were necessary; split-second reactions were expanded to encompass thought and reactions. But now I was going to relate the events of fifty years; I faced many problems I never even guessed about. Somerset Maugham, a writer I much admired, would often write in the first person of a man who observed the events of which he wrote. Maugham’s voice was apt to bridge his narrative with ‘…it was three years before I was to see either of them again, and it was in very different circumstances’. As a reader I rather delighted in this voyeur writer but I didn’t feel confident enough to use such leaps in time. And the frantic pace of German history would not survive a leisurely survey.

I sought advice from my literary agents Jonathan and Ann Clowes – the most widely read friends I have – and examined several family saga novels, old; and new. There was a lot to learn. More than once I decided to abandon my project but while I was sorting and sifting my research notes the solution became evident. I would eliminate connective material. My chapters would be brief human interactions, like flashes of lightning illuminating long nights of darkness. This format would require careful selection of material so that each chapter provided a vital link in the story. And yet Winter must not be a history book; it had to be an interesting and emotive story of a family living through Europe’s nightmare past.

I returned to Vienna. Vienna is a town different to any other that I know. The small central area is defined by the Ringstrasse around which, according to his son, the amazing Sigmund Freud ‘marched at a terrific speed almost every day’. Vienna is not so much a town as a spectacle: if you don’t want to visit Sankt Marxer Friedhof – where Mozart’s corpse was tossed into a common grave – you can chew on the famous chocolates that bear his name. If you don’t like the music of Mahler, what about Franz Lehar? If Klimt is too opulent, what about Schiele? If you don’t like the Hotel Sacher; savour your Sachertorte in Demels. If you don’t fancy Graham Greene’s sewers; seek Harry Lime on the big wheel in the Prater. Vienna has something for everyone; from the Wiener Werkstätte to the Wienerwald. Within the Ringstrasse there are more churches, historic buildings, restaurants and shops than anyone needs. But the greatest wonders of the city are its magnificent old cafes. So you can see why, for anyone inflicted with insatiable curiosity, or easily diverted, Vienna is no place to write books.

I chose Munich because that city uniquely links Vienna with Berlin. The inhabitants of these three great German cities view each other with dispassionate superiority. While the mighty Austria-Hungary Empire dominated Europe, Vienna ruled. It was Bismarck, and the Prussian armies that in 1870 marched into Paris, that displaced Vienna and established Berlin’s ascendancy. At the turn of the century, Berlin’s music hall comics got guaranteed laughs from jokes that depicted Bavarians and the Viennese as hopeless country bumpkins. But Hitler changed all that. Hitler was an Austrian and his Nazi Party was born in Munich and when Hitler named that town as the Hauptstadt der Bewegung – ‘capital of the movement’ – all jokes about its citizens were hushed.

I visited all three cities frequently while working on this book but Munich was the place where it all began. My sons attended a local boarding school at Schondorf, and put their Austrian accents on the shelf. With the aid of my wife, I interrogated anyone old enough to provide me with memories of the old days. I was listening to the recollections of a fellow customer in a stationery shop when I spotted a small grey ‘typewriter’ that turned out to be Hewlett Packard’s radical new product. It was the world’s first laptop: a unique, strange and awkward beast by today’s standards – and started writing.

Len Deighton, 2010

Prologue

Nuremberg 1945

Winter entered the prison cell unprepared for the change that the short period of imprisonment had brought to his friend. The prisoner was fifty-two years old and looked at least sixty. His hair had been thinning for years, but suddenly he’d become a bald-headed old man. He was sitting on the iron frame bed, sallow and shrunken. His elbows were resting on his knees and one hand was propped under his unshaven chin. The prison authorities had taken from him his belt, his braces, and his necktie, and the expensive custom-made suit from Berlin’s most famous tailor was now stained and baggy. And yet the dark-underlined eyes were the same, and the pointed cleft chin made him immediately recognizable as a celebrity of the Third Reich, one of Hitler’s most reliable associates.

‘You sent for me, Herr Reichsminister?’

The prisoner looked up. ‘The Reich is kaputt, Germany is kaputt, and I’m not a minister: I’m just a number.’ Winter could think of no way to respond to the bitter old man. He’d become used to seeing him sitting behind the magnificent hand-carved desk in the tapestry-hung room in the ministry, surrounded by aides, secretaries, and assistants. ‘Yes, I sent for you, Winter. Sit down.’

He sat down. So it was all to be formal.

‘I sent for you, Herr Doktor Winter, and I’ll tell you why. They told me you were in prison in London awaiting interrogation. They said that any of us on trial here could choose any German national we wanted for our defence counsel, and that if the one we chose was being held in prison they’d release him to do it. It seemed to me that a man in prison might know what it’s like for me in here.’

Winter wondered if he should offer the ex-Reichsminister a cigarette, but when – still undecided – he produced his precious cigarettes, the military policeman in the corridor shouted through the open door, ‘No smoking, buddy!’

The ex-Reichsminister gave no sign of having heard the prison guard’s voice. He carried on with his explanation. ‘Two, you speak American …speak it fluently. Three, you’re a damned good lawyer, as I know from working with you for many years. Four, and this is the most important, you are an Obersturmbannführer in the SS…’ He saw Winter’s face change and said, ‘Is there something wrong, Winter?’

Winter leaned forward; it was a gesture of confidentiality and commitment. ‘At this very moment, just a few hundred yards from here, there are a hundred or more American lawyers drafting the prosecution’s case for declaring the SS an illegal organization. Such a verdict would mean prison, and perhaps death sentences, for everyone who was ever a member.’

‘Very well,’ said the prisoner testily. He’d always hated what he called ‘unimportant pettifogging details’. ‘But you’re not going to suddenly claim you weren’t a member of the SS, are you?’

For the first time since the message had come that the minister wanted him as junior defence counsel, Winter felt alarmed. He looked round the cell to see if there were microphones. There were bound to be. He remembered this building from the time when he’d been working with the Nuremberg Gestapo. Half the material used in the trial of the disgruntled brownshirts had come from shorthand clerks who had listened to the prisoners over hidden microphones. ‘I can’t answer that,’ said Winter softly.

‘Don’t give me that yes-sir, no-sir, I-don’t-know-sir. I don’t want some woolly-minded, fainthearted, Jew-loving liberal trying to get my case thrown out of court on some obscure technicality. I sent for you because you got me into all this. I remembered your hard work for the party. I remembered the good times we had long before we dreamed of coming to power. I remembered the way your father lent me money back when no one else would even let me into their office. Pull yourself together, Winter. Either put your guts into the effort for my defence or get out of here!’

Winter admired his old friend’s courage. Appearances could be deceptive: he wasn’t the broken-spirited shell that Winter had thought; he was still the same ruthless old bastard that he had worked for. He remembered that first political meeting in the Potsdamer Platz in the 1920s and the speech he’d given: ‘Beneath the ashes fires still rage.’ It had been a recurring theme in his speeches right up until 1945.

‘We’ll fight them,’ said Winter. ‘We’ll grab those judges by the ankles and shake them until their loose change falls to the floor.’

‘That’s right,’ he said. It was another one of his pet expressions. ‘That’s right.’ He almost smiled.

‘Time’s up, buddy!’

Winter looked at his watch. There was another two minutes to go. The Americans were like that. They talked about justice and freedom, democracy and liberty, but they never gave an inch. There was no point in arguing: they were the victors. The whole damned Nuremberg trial was just a show trial, just an opportunity for the Americans and the British and the French and the Russians to make an elaborate pretence of legal rectitude before executing the vanquished. But it was better that the ex-Reichsminister didn’t fully realize the inevitable verdict and sentence. Better to fight them all the way and go down fighting. At least that would keep his spirits alive. With this resolved, Winter felt better, too. It would be a chance to relive the old days, if only in memories.

When Winter got to the door, the old man called out to him, ‘One last thing, Winter.’ Winter turned to face him. ‘I hear stories about some aggressive American colonel on the prosecution staff, a tall, thin one with a beautifully tailored uniform and manicured fingernails …A man who speaks perfect German with a Berlin accent. He seems to hate all Germans and makes no allowances for anything; he treats everyone to a tongue-lashing every time he sends for them. Now they tell me he’s been sent from Washington just to frame the prosecution’s case against me…’ He paused and stared. He was working himself up into the sort of rage that had sent fear into every corner of his ministry and far beyond. ‘Not for Göring, Speer, Hess, or any of the others, just for me. What do you know about that shit-face Schweinehund?’

‘Yes, I know him. It’s my brother.’

One of the Americans lawyers, Bill Callaghan – a white-haired Bostonian who specialized in maritime law – said, after reading through Winter’s file, that the story of the brothers read like fiction. But that was only because Callaghan was unacquainted with any fiction except the evidence that his shipowning clients provided for him to argue in court.

Fiction had unity and style, fiction had a beginning and a proper end, fiction showed evidence of planning and research and usually attempted to impose an orderly pattern upon the chaos of reality.

But the lives of the Winter brothers were not orderly and had no discernible pattern. Their lives had been a response to parental expectations, historical circumstances, and fleeting opportunities. Ambitions remained unfulfilled and prejudices had been disproved. Diversions, digressions, and disappointments had punctuated their lives. In fact, their lives had been fashioned in the same way as had the lives of so many of those born at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Callaghan, in that swift and effortless way that trial lawyers can so often command, gave an instant verdict on the lives of the Winter brothers. ‘One of them is a success story,’ said Callaghan, ‘and the other is a goddamned horror story.’ Actually, neither was a story at all. Like most people, they had lived through a series of episodes, most of which were frustrating and unsatisfactory.

1899

‘A whole new century’

Everyone saw the imperious man standing under the lamppost in Vienna’s Ringstrasse, and yet no one looked directly at him. He was very slim, about thirty years old, pale-faced, with quick, angry eyes and a neatly trimmed black moustache. His eyes were shadowed by the brim of his shiny silk top hat, and the gaslight picked out the diamond pin in his cravat. He wore a long black chesterfield overcoat with a fur collar. It was an especially fine-looking coat, the sort of overcoat that came from the exclusive tailors of Berlin. ‘I can’t wait a moment longer,’ he said. And his German was spoken with the accent of Berlin. No one – except perhaps some of the immigrants from the Sudetenland who now made up such a large proportion of the city’s population – could have mistaken Harald Winter for a native of Vienna.

The crowd that had gathered around the amazing horseless carriage – a Benz Viktoria – now studied the chauffeur who, having inspected its engine, stood up and wiped his hands. ‘It’s the fuel,’ said the chauffeur, ‘dirt in the pipe.’

‘I’ll walk to the club,’ said the man. ‘Stay here with the car. I’ll send someone to help you.’ Without waiting for a reply, the man pushed his way past a couple of onlookers who were in his way and marched off along the boulevard, jabbing at the pavement with his cane and scowling with anger.

Vienna was cold on that final evening of the 1800s; the temperature sank steadily through the day, until by evening it went below freezing point. Harald Winter felt cold but he also felt a fool. He was mortified when one of his automobiles broke down. He enjoyed being the centre of attention when he was being driven past his friends and enemies in their carriages, or simply being pointed out as the owner of one of the first of the new, expensive mechanical vehicles. But when the thing gave trouble like this, he felt humiliated.

In Berlin it was different. In Berlin they knew about these things. In Berlin there was always someone available to attend to its fits and starts, its farts and coughs, its wheezes and relapses. He should never have brought the machine to Vienna. The Austrians knew nothing about such modern machinery. The only horseless carriage he’d seen here was electric-powered – and he hated electric vehicles. He should never have let his wife persuade him to come here for Christmas: he hated Vienna’s rainy winters, hated the political strife that so often ended in riots, hated the food, and hated these lazy, good-for-nothing Viennese with their shrill accent, to say nothing of the wretched, ragged foreigners who were everywhere jabbering away in their incomprehensible languages. None of them could be bothered to learn a word of proper German.

He was chilled by the time he turned through big gates and into an entranceway. Like so many of the buildings in this preposterous town, the club looked like a palace, a heavy Baroque building writhing with nymphs and naiads, its portals supported by a quartet of herculean pillars. The doorman signalled to the door porters so that he was admitted immediately to the brightly lit lobby. It was normally crowded at this time of evening, but tonight it was strangely quiet.

‘Good evening, Herr Baron.’

Winter grunted. That was another thing he hated about Vienna: everyone had to have a title, and if, like Winter, a man had no title, the servants would invent one for him. While one servant took his cane and his silk hat, another slipped his overcoat from his shoulders.

Without hat and overcoat, it was revealed that Harald Winter had not yet changed for dinner. He wore a dark frock coat with light-grey trousers, a high stiff collar and a slim bow-tie. His pale face was wide with a pointed chin, so that he looked rather satanic, an effect emphasized by his shiny black hair and centre parting.

‘Winter! What a coincidence! I’m just off to see your wife now.’ The speaker was Professor Doktor Franz Schneider, fifty years old, the best, or at least the richest and most successful, gynaecologist in Vienna. He was a small, white-faced man, plump in the way that babies are plump, his skin flawless and his eyes bright blue. Nervously he touched his white goatee beard before straightening his pince-nez. ‘You heard, of course…. Your wife: the first signs started an hour ago. I’m going to the hospital now. You’ll come with me? My carriage is here, waiting.’ He spoke hurriedly, his voice pitched higher than normal. He was always a little nervous with Harald Winter; there was no sign now of the much-feared professor who met his students’ questions with dry and savage wit.

Winter’s eyes went briefly to the door from which Professor Schneider had come. The bar. Professor Schneider flushed. Damn this arrogant swine Winter, he thought. He could make a man feel guilty without even saying a word. What business of Winter’s was it that he’d had a mere half-bottle of champagne with his cold pheasant supper? It was Winter’s wife whose pangs of labour had come on New Year’s Eve, and so spoiled his chance of getting to the ball at anything like a decent time.

‘I have a meeting,’ said Winter.

‘A meeting?’ said Professor Schneider. Was it some sort of joke? On New Year’s Eve, what man would be attending a meeting in a club emptied of almost everyone but servants? And how could a man concentrate his mind on business when his wife was about to give birth? He met Winter’s eyes: there was no warmth there, no curiosity, no passion. Winter was said to be one of the shrewdest businessmen in Germany, but what use were his wealth and reputation when his soul was dead? ‘Then I shall go along. I will send a message. Will you be here?’

Winter nodded almost imperceptibly. Only when Professor Schneider had departed did Winter go up the wide staircase to the mezzanine floor. Another member was there. Winter brightened. At last, a face he knew and liked.

‘Foxy! I heard you were in this dreadful town.’

Erwin Fischer’s red hair had long since gone grey – a great helmet of burnished steel – but his nickname remained. He was a short, slight, jovial man with dark eyes and sanguine complexion. His great-grandparents had been Jews from the Baltic city of Riga. His grandfather had changed the family name, and his father had converted to Roman Catholicism long before Erwin was born. Fischer was heir to a steel fortune, but at seventy-five his father was fit and well and – now forty-eight years old – Fuchs Fischer had expectations that remained no more than expectations. Erwin was a widower. He wasn’t kept short of money, but he was easily bored, and money did not always assuage his boredom. His life had lately become a long, tedious round of social duties, big parties, and introductions to ‘suitable marriage partners’ who never proved quite suitable enough.

‘You give Bubi Schneider a bad time, Harald. Is it wise? He has a lot of friends in this town.’

‘He’s a snivelling little parasite. I can’t think why my wife consulted such a man.’

‘He delivers the children of the most powerful men in the city. The wives confide in him, the children are taught to think of him as one of the family. Such a man wields influence.’

Winter smiled. ‘Am I to beware of him?’ he said icily.

‘No, of course not. But he could cause you inconvenience. Is it worth it, when a smile and a handshake are all he really wants from you?’

‘The wretch insisted that Veronica could not travel back to Berlin. My son will be born here. I don’t want an Austrian son. You are a German, Foxy; you understand.’

‘So it’s to be a son. You’ve already decided that, have you?’

Winter smiled. ‘Shall we crack a bottle of Burgundy?’

‘You used to like Vienna, Harald. When you first bought the house here you were telling us all how much better it was than Berlin.’

‘That was a long time ago. I was a different man then.’

‘You’d discovered your wonderful wife in Berlin and Veronica here in Vienna. That’s what you mean, isn’t it.’

‘Don’t go too far, Foxy.’

The older man ignored the caution. He was close enough to Winter to risk such comments, and go even further. ‘Surely you’ve taken into account the possibility that it was Veronica’s idea to have the baby here.’

‘Veronica?’

‘Consider the facts, Harald. Veronica met you here when she was a student at the university. This is where she first learned about love and life and all the things she’d dreamed about when she was a little girl in America. She adores Vienna. No matter that you see it as a second-rate capital for a fifth-rate empire; for Veronica it’s still the home of Strauss waltzes and parties where she meets dukes, duchesses, and princes of royal blood. No matter what you say, Harald, Kaiser Wilhelm’s Berlin cannot match Vienna in the party season. Would you really be surprised to find that she had contrived to have the second child here?’

‘I hope you haven’t…’

‘No, I haven’t spoken with her, of course I haven’t. I’m simply telling you to ease the reins on Bubi Schneider until you’re quite sure it’s all his fault.’

Winter stepped away and leaned over the gilt balcony. Resting his hand upon a cherub, he signalled to a club servant on the floor below. ‘Send a bottle of the best Burgundy up to us. And three glasses.’

They went to a long, mirrored room, the chandeliers blazing from a thousand reflections. A fire was burning at the far end of the room. The open fireplace was a daring innovation for Vienna, a city warmed by stoves, but the committee had copied the room from a gentlemen’s club in London.

Over the fireplace there was a huge painting of the monarch who combined the roles of emperor of Austria and king of Hungary and insisted upon being addressed as ‘His Apostolic Majesty, our most gracious Emperor and Lord, Franz Joseph I.’ The room was otherwise empty. Winter chose a table near the fire and sat down. Fischer stood with his hands in his pockets and stared out the window. Winter followed his gaze. Across the dark street a wooden stand had been erected for a political meeting held that morning. Now no one was there except two uniformed policemen, who stood amongst the torn slogans and broken chairs as if such impedimenta did not exist for them.

‘I’ve never understood women,’ said Winter finally.

‘You’ve always understood women only too well,’ said Fischer, still looking out the window. ‘It’s Americans you don’t understand. It’s because Veronica is an American that your marriage is sometimes difficult.’

‘You told me at the time, Foxy. I should have listened.’

‘No European man in his right senses marries an American girl. You’ve been lucky with Veronica: she doesn’t fuss too much about your other women or try to stop you drinking or going to those parties at Madame Reiner’s mansion. For an American woman she’s very understanding.’ There was a note of humour in Fischer’s voice, and now he turned his head to see how Winter was taking it. Noticing this, Winter permitted himself the ghost of a smile.

A waiter entered and took his time showing Winter the label and then pouring two glasses of wine with fastidious care.

Fischer sipped his wine, still looking down at the street. The plain speaking had divided the two men, so that now they were isolated in their thoughts. ‘The wine steward found you something good, Harald,’ said Fischer appreciatively, pursing his lips and then tasting a little more.

‘I have my own bin,’ said Winter. ‘I no longer drink from the club’s cellar.’

‘How sensible.’

Winter made no reply. He drank the wine in silence. That was the difference between them. Fischer, the rich man’s son, took everything for granted and left everything to chance. Harald Winter, self-made tycoon, trusted no one and left nothing to chance.

‘I was here this morning,’ said Fischer. He motioned down towards the street where the political demonstration had been held. ‘Karl Lueger spoke. After he’d stepped down there was fighting. The police couldn’t handle it; they brought in the cavalry to clear the street.’

‘Lueger is a rogue,’ said Winter quietly and without anger.

‘He’s the mayor.’

‘The Emperor should never have ratified the appointment.’

‘He blocked it over and over again. Finally he had to do as the voters wanted.’

‘Voters? Riffraff. Look at the slogans down there – “Save the small businessman”; “Bring the family back into church”; “Down with Jewish big business” – the Christian Socials just pander to the worst prejudice, fears, and bitter jealousy. “Handsome Karl” is all things to all men. For those who want socialism he’s a socialist; for churchgoers he’s a man of piety; for anyone who wants to hang the Jews, or hound Hungarians back across the border, his party is the one to vote for. What a rascal.’

‘You’re a man of the world; you must realize that hating foreigners is a part of the Austrian psyche. How many votes would you get for telling those people down there that the Jew is brainier than they are, or that these immigrant Czechs and Hungarians are more hard working?’

‘I don’t like it, Foxy. Lueger is becoming as popular as the Emperor. Sometimes I have the feeling that Lueger could become the Emperor. Suppose all this hatred, all this Judenhass, was organized on a national scale. Suppose someone came along who had Lueger’s cunning with the crowd, the Emperor’s sway with the army, and a touch of Bismarck’s instinct for Geopolitik. What then, Foxy? What would you say to that?’

‘I’d say you need a holiday, Harald.’ He tried to make a joke of it, but Winter did not join in his forced laugh. ‘Who is the third glass for, Harald? Am I allowed to know that?’ He knew it wasn’t a woman: no women were ever permitted on the club premises.

‘The mysterious Count Kupka sent a messenger to my home today.’

‘Kupka? Is he a personal friend?’ There was a strained note in Fischer’s normally very relaxed voice.

‘Personal friend? Not at all. I have met him, of course, at parties and even at Madame Reiner’s mansion, but I know nothing about him except that he is said to have the ear of the Emperor and to be some sort of consultant to the Foreign Ministry.’

‘You have a lot to learn about this city, Harald. Count Kupka is the head of the Emperor’s secret police. He is responsible to the Foreign Ministry, and the minister answers only to His Majesty. Kupka’s signature on a piece of paper is all that’s needed to make a man disappear forever.’

‘You make him sound interesting, Foxy. He always seemed such a desiccated and boring little man.’

Fischer looked at his friend. Harald Winter was clearly undaunted by Kupka. It was Winter’s bravery that Fischer had always found attractive. He admired Winter’s audacious, if not to say reckless, business ventures, and his brazen love affairs, and his indifference to the prospect of making enemies like Professor Schneider. Sometimes Fischer was tempted to think that Harald Winter’s courage was the only attractive aspect of this ruthless, selfish man. ‘We’ve known each other a long time, Harald. If you’re in trouble, perhaps I can help.’

‘Trouble? With Kupka? I can’t think how I could be.’

‘It’s New Year’s Eve, Harald. At midnight a whole new century begins: the twentieth century. Everyone we know will be celebrating. There is a State Ball where half the crowned heads of Europe will be seen. Why would Count Kupka have to see you tonight of all nights?’

‘It is something that perhaps you should stay and ask him yourself, Foxy. He is already twenty minutes late.’

Fischer finished his glass of wine in one gulp. ‘I won’t stay. The man gives me the shudders.’ He put the glass on the table alongside the polished one that was waiting for Count Kupka. ‘But let me remind you that tonight the streets will be empty except for some drunken revellers. For someone who was going to bundle a man into a carriage, or throw someone into the Danube, tonight would provide a fine opportunity.’

Winter smiled broadly. ‘How disappointed you will be tomorrow, Foxy, when it is revealed that Count Kupka wanted no more than a chance to ride in my horseless carriage.’

In fact, Kupka didn’t want a ride in Winter’s horseless carriage; or if he did, he made no mention of this desire. Nor was Count Kupka the desiccated and boring little man that Winter remembered. Kupka was a broad-shouldered man with large, awkward hands that did not seem to go with his pale, lined face and delicate eyebrows, that had been plucked so that they didn’t meet across the top of his thin, pointed nose. Kupka’s head was large: like a balloon upon which a child had scrawled his simple, expressionless features. And, like paint upon a balloon, his hair – shiny with Macassar oil – was brushed flat against his head.

Kupka was still wearing his overcoat when he strode into the lounge. His silk hat was tilted slightly to the back of his head. He put his cane down and removed his gloves, holding his cigar between his teeth. Winter didn’t move. Kupka tossed the gloves down. Winter continued to sip his Burgundy, watching Kupka with the amused and indulgent interest that he would give to an entertainer coming onto the stage of a variety theatre. Winter could recall only two other men who smoked large cigars while walking about in hat and overcoat, and both of those were menials in his country house. It amused him that Kupka should behave in such a way.

‘I am greatly indebted to you, Winter. It is most kind of you to consent to seeing me at such short notice.’ Kupka flicked ash from his cigar. ‘Especially tonight of all nights.’

‘I knew it would be something that couldn’t wait,’ said Winter with an edge in his voice that he did nothing to modify.

‘Yes, yes, yes,’ said Kupka in a voice that suggested that his mind had already passed on to the next thought. ‘Was that Erwin Fischer I passed on the stairs?’

‘He was taking a glass of Burgundy with me. Perhaps you’d do the same, Count Kupka?’

‘There is nothing that would give me greater pleasure, Herr Winter….’ Before Winter could reach for the bottle and pour, Kupka held up his hand so that gold rings, some inset with diamonds, sparkled in the light of the chandeliers. ‘But, alas, I have an evening of work before me.’ Winter poured wine for himself and Kupka said, ‘And I will be as brief as I can.’

‘I would appreciate that,’ said Winter. ‘Won’t you sit down?’

‘Sometimes I need to stand. They say that, at the Opera, Mahler stands up to conduct his orchestra. Stands up! Most extraordinary, and yet I sympathize with the fellow. Sometimes I can think better on my feet. Yes … your wife. I saw Professor Doktor Schneider earlier this evening. Women are such frail creatures, aren’t they? The problem concerning which I must consult you comes about only because of my dear wife’s maternal affection for a distant cousin.’ Kupka paused a moment to study the burning end of his cigar. ‘He is rather a foolish young man. But no more foolish than I was when young, and no more foolish than you were, Winter.’

‘Was I foolish, Count Kupka?’

Kupka looked at him and raised his eyebrows to feign surprise. ‘More than most, Herr Winter. Have you already forgotten those hotheads you mixed with when you were a student? The Silver Eagle Society you called yourselves, as I remember. And you a student of law, too!’

Despite doing everything he could to remain composed, Winter was visibly shaken. When he spoke his voice croaked: ‘That was no more than a childish game.’ He drank some wine to clear his throat.

‘For you perhaps, but not for everyone who joined it. Suppose I told you that the anarchist who killed our Empress last year could also be connected to an organization calling itself the Silver Eagle?’ Kupka glanced up at the portrait of the Emperor and then warmed his hands at the fire.

‘If you told me that, then I would know that you are playing a childish game.’

‘And if I persisted?’ Kupka smiled. There was no perceptible cruelty in his face. He was enjoying this little exchange and seemed to expect Winter to enjoy it also. But for Winter the stakes were too high. No matter how unfounded such accusations might be, it would need only a few well distributed rumours to damage Winter and his family forever.

‘Then I would call you out,’ said Winter with all the self-assurance he could muster.

Kupka laughed. ‘A duel? Save that sort of nonsense for the Officer Corps. I am no more than an Einjährig-Freiwilliger, and one-year volunteers don’t learn how to duel.’ Kupka sat down opposite Winter and carelessly tapped ash into the fireplace. ‘Now that I see the label on that bottle of wine, perhaps I could change my mind about a glass of it.’

Winter poured a glass. The work of the picador was done, the temper and the weaknesses of the bull discovered: now Kupka the matador would enter the ring.

‘About this lad,’ said Kupka after sipping the wine. ‘He borrowed money from your bank.’

‘Hardly my bank,’ said Winter. He’d come prepared. Kupka’s message had mentioned this client of the bank.

‘The one in which some unnamed discreet person holds eighteen thousand nominee shares. The one in which you have an office and a secretary. The one in which the manager refers all transactions above a prescribed amount to you for approval. My wife’s distant cousin borrowed money from that bank.’

‘You want details?’

‘I have all the necessary details, thank you. I simply want to give you the money.’

‘Buy the debt?’ said Winter.

‘Plus an appropriate fee to the bank.’

‘The name was Petzval; he said his family was from Budapest. The manager was doubtful, but he seemed a sensible lad.’

‘Petzval, yes. My wife worries about him.’

‘A distant cousin, you say?’

‘My wife’s family is a labyrinth of distant cousins and so on. A fine wine, Winter. I have not seen it on the wine list,’ said Kupka, and poured himself some more. ‘She worries about the debt.’

‘What does she think I will do to him?’ Winter asked.

‘Not you, my dear friend. My goodness, no. She worries that he will get behind in his payments to you and go to a money-lender. You know what that can lead to. I see so many lives ruined,’ said Kupka without any sign of being downcast. ‘He wants to write a book. His family have nothing. Believe me, Winter, it’s a debt you will be better without.’

‘I will inquire into the facts,’ said Winter.

‘The payment can be made in any way that you wish it – paper money, gold, a certified cheque – and anywhere – New York, London, Paris, or Berlin.’

‘Your concern about this young man touches me,’ said Winter.

‘I am a sentimental fool, Winter, and now you have discovered the truth of it.’ Ash went down Kupka’s overcoat, but he didn’t notice.

A club servant entered the lounge looking for Winter. ‘There is a telephone call for you, Herr Baron.’

‘It will be the hospital,’ explained Winter.

‘I have detained you far too long,’ said Kupka. He stood up to say goodbye. ‘Please give my compliments and sincere apologies to your beautiful wife.’ He didn’t press for an answer; men such as Kupka know that their requests are never refused.

‘Auf Wiedersehen, Count Kupka.’

‘Auf Wiedersehen, my dear Winter.’ He clicked his heels and bowed.

Winter followed the servant downstairs. The club had only recently been connected to the telephone. Even now it was not possible for a caller to speak to the staff at the entrance desk; the facility whereby wives could inquire about their husbands’ presence in the club would not be a welcome innovation. The instrument was enshrined upon a large mahogany table in a room on the first floor. A servant was permanently assigned to answer it.

‘Winter here.’ He wanted to show both the caller and the servant that telephones were not such rarities in Berlin.

‘Winter? Professor Schneider speaking. A false alarm. These things happen. It could be two or three days.’

‘How is my wife?’

‘Fit and well. I have given her a mild sedative, and she will be asleep by now. I suggest you get a good night’s sleep and see her tomorrow morning.’

‘I think I will do that.’

‘Your baby will be born in 1900: a child of the new century.’

‘The new century will not begin until 1901. I would have thought an educated man like you would know that,’ said Winter, and replaced the earpiece on the hook. Already the bells were ringing. Every church in the city was showing the skills of its bellringers to welcome the new year. But in the kitchen a dog was whining loudly: the bells were hurting its ears. Dogs hate bells. So did Harald Winter.

‘What good jokes you make, Liebchen’

Martha Somló was beautiful. This petite, dark-haired, large-eyed daughter of a Jewish tailor was one of twelve children. The family had originally come from a small town in Rumania. Martha grew up in Hungary, but she arrived in Vienna alone, a sixteen-year-old orphan. She was working in a cigar shop when she first met Harald Winter. Within three weeks of that meeting he had installed her in an apartment near the Votivkirche. Now she was eighteen. She had a much grander place to live. She also had a lady’s maid, a hairdresser who came in every day, an account with a court dressmaker, some fine jewellery, and a small dog. But Harald Winter’s visits to Vienna were not frequent enough for her, and when he wasn’t with her she was dispirited and lonely.

Harald Winter’s mistress was no more than a small part of his curious and complex relationship with Vienna. He’d spent a lot of time in finding this wonderful apartment with its view of the Opera House and the Wiener Boulevard. From here she could watch ‘Sirk-Ecke’, a sacred meeting place for Vienna’s high society, who paraded up and down in their finest clothes every day except Sunday.

Once found, the apartment had been transformed into a showplace for Vienna’s newly formed ‘Secession’ art movement. A Klimt frieze went completely round the otherwise shiny black dining room, where the table and chairs were by Josef Hoffmann. The study, from writing desk to notepaper, was completely the work of Koloman Moser. Everywhere in the apartment there were examples of Art Nouveau. Martha Somló felt, with reason, that she was little more than a curator for an art museum. She hated everything about the apartment that Harald Winter had so painstakingly put together, but she was too astute to say so. Winter’s American wife, Veronica, had made no secret of her dislike for modern art, and the end result of that was the apartment in Kärntnerstrasse and Martha. If Martha made her true feelings known, there was little chance that Winter would get rid of his treasures; he’d get rid of her. It would be easier, quicker, and cheaper.

‘I love you, Harry,’ she said suddenly and without premeditation.

‘What was that?’ said Winter. He was in his red silk dressing gown, the one she’d chosen for him for his thirtieth birthday. It had been a wonderful day of shopping, followed by an extravagant party at Sachers. That was six months ago: now they hardly ever went anywhere together. Since his wife had become pregnant with this second child, he’d become more distant, and she worried that he was trying to find some way to tell her he didn’t want her any more. ‘I think I must be getting deaf; my father went deaf when very young.’

She went to him and threw her arms round his neck and kissed him. ‘Harry, you fool. You’re not going deaf; you’re the strongest, fittest man I ever met. I say I love you, Harry. Smile, Harry. Say you love me.’

‘Of course I love you, Martha.’ He kissed her.

‘A proper kiss, Harry. A kiss like the one you gave me when you arrived this afternoon hungering for me.’

‘Dear Martha, you’re a sweet girl.’

‘What’s wrong, Harry? You’re not yourself today. Is it something to do with the bank?’

He shook his head. Things were not too good at the bank, but he never discussed his business troubles with Martha and he never would. Women and business didn’t mix. Winter wasn’t entirely sure about women being admitted to universities. On that account he sometimes felt more at ease with women like Martha than with his own wife. Martha understood him so well.

‘Do you know who Count Kupka is?’

‘My God, Harry. You’re not in trouble with the secret police? Oh, dear God, no.’

‘He wants a favour from me, that’s all.’

She sat down and pulled him so that he sat with her on the sofa. He told her something about the conversation he’d had with Kupka.

‘And you found out what he wanted to know?’ She stroked his face tenderly. Then she looked at the leather document case that Winter had brought with him to the apartment. He rarely carried anything. Many times he’d told her that carrying cases, boxes, parcels, or packages was a task only for servants.

‘It’s not so easy,’ said Winter. She could see he wanted to talk about it. ‘My manager asked for collateral. This fellow owns land on the Obersalzberg. All the paperwork has been done to make the land the property of the bank if he defaults on the loan. I have now changed matters so that the loan has come from my personal account. Luckily the land deed is already made over to a nominee, so I get it in case of a default.’

‘Salzburg, Harry? Austria?’

‘Not Salzburg; the Obersalzberg. It’s a mountain a thousand metres high. It’s not in Austria: it’s just across the border, in Bavaria.’

‘In Germany?’

‘And that’s going to be another problem. I’m not sure it’s possible to turn everything over to Kupka.’

‘He’ll say you’re not cooperating,’ she said. She had heard of Kupka. What Jew in the whole of the empire had not heard of him. She was sick with fear at the mention of his name.

‘Kupka is a lawyer,’ said Winter confidently.

‘That’s like saying Attila the Hun was a cavalry officer,’ she said.

Winter laughed loudly and embraced her. ‘What good jokes you make, Liebchen. I’m tempted to tell Kupka that one.’

‘Don’t, Harry.’

‘You mustn’t be frightened, my darling. I am simply a means to an end in this matter.’

‘Just do what he says, Harry.’

‘But not yet, I think. Tonight I’m meeting this mysterious fellow Petzval at the Café Stoessl in Gumpendorfer Strasse. Damn him – I’ll get from him everything that Kupka won’t tell me.’

‘Remember he’s a relative of Kupka’s, and close to his wife.’

‘Rubbish,’ said Winter. ‘That was just a smokescreen to hide the true facts of the matter.’

‘Send someone,’ she suggested.

He smiled and went to the leather case he’d brought with him. From it he brought a small revolver and a soft leather holster with a strap that would fit under his coat.

‘If Kupka has his men there, a pistol won’t save you.’

‘Little worrier,’ he said affectionately and kissed her.

She held him very tight. How desperately she envied his wife; the children would always bind Harry to her in a way that nothing else could. If only Martha could give him a wonderful son.

1900

A plot of land on the Obersalzberg

It was dark by the time that Winter pushed through the revolving door of the Café Stoessl in the Gumpendorfer Strasse and looked around. The café was long and gloomy, lit by gaslights that hissed and popped. There were tables with pink marble tops and bentwood chairs and plants everywhere. He recognized some of the customers but gave no sign of it. They were not people that Winter would acknowledge: the usual crowd of would-be intellectuals, has-been politicians, and self-styled writers.

Petzval was waiting. ‘A small Jew with a black beard,’ the bank manager had told Winter. Well, that was easy. Petzval sat at the very end table facing towards the door. He was a white-faced man in his late twenties, with bushy black hair and a full beard so that his small eyes and pointed nose were all you noticed of his face.

Winter put his hat on a seat and then sat down opposite the man and ordered a coffee, and brandy to go with it. Then he apologized vaguely for being late.

‘I said you’d go back on your word,’ said Petzval.

It wasn’t a good beginning, and Winter was about to deny any such intention, but then he realized that such an opening would leave him little or no room for discussion. ‘Why did you think that?’ asked Winter.

‘Count Kupka, is it?’ Petzval leaned forward and rested an elbow on the table.

Winter hesitated but, after looking at Petzval, decided to admit it. Kupka had claimed Petzval as a relative and had not asked Winter to keep his name out of it. ‘Yes, Count Kupka.’

‘He wants to buy my debt?’

‘Something along those lines.’

Petzval pushed his empty coffee cup aside so that he could lean both arms on the table. His face was close to Winter, closer than Winter welcomed, but he didn’t shrink away. ‘Secret police,’ said Petzval. ‘His spies are everywhere.’

‘Are you related to Kupka?’ said Winter.

‘Related? To Kupka?’ Petzval made a short throaty noise that might have been a laugh. ‘I’m a Jew, Herr Winter. Didn’t you know that when you made the loan to me?’

‘It would have made no difference one way or the other,’ said Winter. The coffee came, and Winter was glad of the chance to sit back away from the man’s glaring eyes. This was a man at the end of his tether, a desperate man. He studied the angry Jew as he sipped his coffee. Petzval was a ridiculous fellow with his frayed shirt and gravy-spattered suit, but Winter found him rather frightening. How could that be, when everyone knew that Winter wasn’t frightened of any living soul?

‘I’m a good risk, am I?’

‘The manager obviously thought so. What do you do, Herr Petzval?’

‘For a living, you mean? I’m a scientist. Ever heard of Ernst Mach?’

He waited. It was not a rhetorical question; he wanted to know whether Winter was intelligent enough to understand.

‘Of course: Professor Mach is a physicist at the university.’

‘Mach is the greatest scientific genius of modern times.’ He paused to let that judgement sink in before adding, ‘A couple of years ago he suffered a stroke, and I’ve been privileged to work for him while pursuing my own special subject.’

‘And what is your subject?’ said Winter, realizing that this inquiry, or something like it, was expected of him.

‘Airflow. Mach did the most important early work in Prague before I was born. He pioneered techniques of photographing bullets in flight. It was Mach who discovered that a bullet exceeding the speed of sound creates two shock waves: a headwave of compressed gas at the front and a tailwave created by a vacuum at the back. My work has merit, but it’s only a continuation of what poor old Professor Mach has abandoned.’

‘Poor old Professor Mach?’

‘He’s too sick. He’ll have to resign from the university; his right side is paralysed. It’s terrible to see him trying to carry on.’

‘And what will you do when he resigns?’ He sipped some of the bitter black coffee flavoured with fig in the Viennese style. Then he tasted the brandy: it was rough but he needed it.

Petzval stared at Winter pityingly. ‘You don’t understand any of it, do you?’

‘I’m not sure I do,’ admitted Winter. He dabbed brandy from his lips with the silk handkerchief he kept in his top pocket, and looked round. There was a noisy group playing cards in the corner, and two or three strange-looking fellows bent over their work. Perhaps they were poets or novelists, but perhaps they were Kupka’s men keeping an eye on things.

‘Don’t you realize the difference between a high-velocity artillery piece and a low-muzzle-velocity gun?’

Winter almost laughed. He’d met evangelists in his time, but this man was the very limit. He talked about the airflow over missiles as other men spoke of the second coming of our Lord. ‘I don’t think I do,’ admitted Winter good-naturedly.

‘Well, Krupp know the difference,’ said Petzval. ‘They have offered me a job at nearly three times the salary that Mach gets from his professorship.’

‘Have they?’ said Winter. He was impressed, and his voice revealed it.

Petzval smiled. ‘Now you’re beginning to see what it’s all about, are you? Krupp are determined to build the finest guns in the world. And they’ll do it.’

Winter nodded soberly and remembered how the Austrian army had been defeated not so long ago by Prussians using better guns. It was natural that the Austrians would want to know what the German armament companies were doing. ‘Count Kupka is interested in your job at Krupp? Is that it?’

‘He wants me to report everything that’s happening in their research department. By taking over the debt he can put pressure on me. That’s why I want the bank to fulfil its obligations.’ Petzval kept his voice to a whisper, but his eyes and his flailing hands demonstrated his passion.

‘It’s not so easy as that.’

‘You have the land on the Obersalzberg. It’s valuable.’

‘Even so, it might be better to do things the way Count Kupka wants them done.’

‘You, a German, tell me that?’

Warning bells rang in Winter’s head. Was Petzval an agent provocateur, sent to test Winter’s attitude towards Austria? It seemed possible. Wouldn’t such military espionage against Krupp be arranged by Colonel Redl, the chief of Austria’s army intelligence? Or was Count Kupka just trying to steal a march on his military rival? ‘It might be best for everyone,’ said Winter.

‘Not best for me,’ said Petzval. ‘I’m not suited to spying. I leave that sort of dirty work to the people who like it. Can you imagine what it would be like to spend every minute of the day and night worrying that you’d be discovered?’

‘You could make sure you’re not discovered,’ said Winter.

‘How could I?’ said Petzval, dismissing the idea immediately. ‘They’d want me to photograph the prototypes and steal blueprints and sketch breech mechanisms and so on.’ He’d obviously thought about it a lot, or was this all part of Count Kupka’s schooling?

‘It would be for your country,’ said Winter, now convinced that it was an attempt to subvert him.

‘Have you ever been in an armaments factory?’ said Petzval. ‘Or, more to the point, have you ever gone out through the gate? At some of those places they search every third worker. Now and again they search everyone. Police raid the homes of employees. I’d be working in the research laboratory and I am a Jew. What chance would I have of remaining undetected?’

Winter glanced round the café. Despite their lowered voices, this fellow’s emotional speeches would soon be attracting attention to them. ‘I’m sorry, Herr Petzval,’ Winter said, ‘but I can’t help you further.’

‘You’ll pass it to him?’ Was it fear or contempt that Winter saw in those dark, deep-set eyes?

‘You read the agreement and signed it. There was nothing to say it couldn’t be passed on to a third party.’

‘A third party? The secret police?’

‘Raise money from another source,’ said Winter. It seemed such a lot of fuss about nothing.

‘I’m deeply in debt, Herr Winter. I beg you to take the land in full payment for the debt.’

‘I couldn’t agree to that. Your prospects…’

‘What prospects do I have if Kupka prevents me from leaving the country?’

‘If Kupka prevents you from leaving Austria…’ For a moment Winter was puzzled. Then he realized what the proposal really was. ‘Do you mean that you came here hoping that I would refuse to do as Kupka demands but not tell him so until you were across the border?’

‘You’re a German.’

‘So you keep reminding me,’ said Winter. He gulped the rest of his brandy. ‘But I have business interests here, and a house. How can you expect me to defy the authorities for a stranger?’

‘For a client,’ said Petzval. ‘I’m not a stranger; I’m a client of the bank.’

‘But you ask too much,’ said Winter. He got up, reached for his hat, and tossed some coins onto the table. It was more than enough to pay for his coffee and the brandy, as well as any coffees and brandies that Petzval might have consumed while waiting for him. ‘Auf Wiedersehen, Herr Petzval.’ As Winter walked down the café he heard some sort of commotion, but he didn’t turn until he heard Petzval shouting.

Petzval was standing and shaking his fist. Then he grabbed the coins and with all his might threw them at Winter. At least two of the coins hit the glass of the revolving doors. Winter flinched. There was a demon in this fellow Petzval. Two waiters grabbed him, but still he struggled to free himself, so that a third waiter had to clamp his arms round Petzval’s neck.

‘Damn you, Winter! And damn your money! I curse you, do you hear me?’

Winter was trembling as he pushed his way through the revolving doors and out into the darkness of Gumpendorfer Strasse. Of course the fellow was quite mad, but his curses were still ringing in Winter’s head as he climbed into his horseless carriage. He couldn’t help thinking it was a bad omen: especially with his second child about to be born at almost any moment.

Winter woke up and wondered where he was for a moment before remembering that he was in his Vienna residence. It seemed so different without his wife. Usually a good night’s sleep was all that Harald Winter needed to recuperate from the stresses and anxieties of his business. But next morning, sitting in his dressing room with a hot towel wrapped across his face, he had still not forgotten his encounter with the violent young man.

Winter removed the hot towel and tossed it onto the marble washstand. ‘Will there be a war, Hauser?’ Winter asked while his valet poured hot water from the big floral-patterned jug and made a lather in the shaving cup.

The valet lathered Winter’s chin. He was an intelligent young man from a village near Rostock. He treasured his job as Winter’s valet; he was the only member of Winter’s domestic household who unfailingly travelled with his master. ‘Between these Austrians and the Serbs, sir? Yes, people say it’s sure to come.’ The razors, combs and scissors were sterilized, polished bright, and laid out precisely on a starched white cloth. Everything was always arranged in this same pattern.

‘Soon, Hauser?’

The valet stopped the razor. He was too bright to imagine that his master was consulting him about the likelihood of war. Such predictions were better left to the generals and the politicians, the sort of men whom Winter rubbed shoulders with every day. Hauser was being asked what people said in the streets. The sort of people who lived in the huge tenement blocks near the factories; workers who lived ten to a room, with all of them paying a quarter of their wages to the landlords. Men who worked twelve-and even fourteen-hour days, with only Sunday afternoons for themselves. What were these men saying? What were they saying in Berlin, in Vienna, Budapest and London? Winter always wanted to know such things and Hauser made it his job to have answers. ‘These Austrians like no one, sir. They are jealous of us Germans, hate the Czechs and despise the Hungarians. But the Serbs are the ones they want to fight. Sooner or later everyone says they’ll finish them off. And Serbia is not much; even the Austrians should be able to beat them.’ He spoke of them all with condescension, as a German has always spoken of the Balkan people and the Austrians, who seemed little different.

Winter smiled to himself. Hauser had all the pride – arrogance was perhaps the better word – of the Prussian. That’s why he liked him. Hauser steadied his master’s chin with finger and thumb as he drew the sharpened razor through the lather and left pink, shiny skin. As Hauser wiped the long razor on a cloth draped over his arm, Winter said, ‘The terrorists and the anarchists with their guns and bombs …murdering innocent people here in the streets. They are all from Serbia. Trained and encouraged by the Serbs. Wouldn’t you be angry, Hauser?’

‘But I wouldn’t join the army and march off to war, Herr Winter.’ He lifted Winter’s chin so that he could bring the razor up the throat. ‘There are lots of people I don’t like, but I can see no point in marching off to fight a war about it.’

‘You’re a sensible fellow, Hauser.’

‘Yes, Herr Winter,’ said Hauser, twisting Winter’s head as he continued his task.

‘We are fortunate to live in an age when wars are a thing of the past, Hauser. No need for you to have fears of riding off to war.’

‘I hope not,’ said Hauser, who had no fears about riding off to war: only gentlemen like Herr Winter went off to war on chargers; Hauser’s class marched.

‘Battles, yes,’ said Winter. ‘The Kaiser will have to teach the Chinese a lesson, the English send men into the Sudan or to fight the Boers – but these are just police actions, Hauser. For us Europeans, war is a thing of the past.’

Hauser turned his master’s head a little more and started to trim the sideburns. He cut them a fraction shorter each time. Side whiskers were fast going out of fashion and, like most domestic servants, Hauser was an unrepentant snob about fashions. He always left Winter’s moustache to the end. Trimming the blunt-ended moustache was the most difficult part. He kept another razor solely for that job. ‘So the Austrians won’t fight the Serbs?’ said Hauser as if Winter’s decision would be final.

‘The Balkans are not Europe,’ said Winter, turning to face the wardrobe so that Hauser could trim the other sideburn. ‘Those fellows down in that part of the world are quite mad. They’ll never stop fighting each other. But I’m talking about real Europeans, who have finally learned how to live together, and settle differences by negotiation: Germans, Austrians, Englishmen … even the French have at last reconciled themselves to the fact that Alsace and Lorraine are German. That’s why I say you’ll never ride off to war, Hauser.’

‘No, Herr Winter, I’m sure I won’t.’

There was a light tap at the door. Hauser lifted his razor away in case his master should make a sudden move. ‘Come in,’ said Winter.

It was one of the chambermaids; little more than fourteen years old, she had a Carinthian accent so strong that Winter had her repeat her message three times before he was sure he had it right. It was the senior manager from the Vienna branch of the bank. What could have got into the man, that he should come disturbing Winter at nine-thirty in the morning at his residence? And yet he was usually a sensible and restrained old man. ‘Very urgent,’ said the little chambermaid. Her face was bright red with excitement at such unusual goings-on. She’d seen the master being shaved; that would be something to brag about to the parlourmaid. ‘Very, very urgent.’

‘That’s quite enough, girl,’ said Hauser. ‘Your master understands.’

‘Show him up,’ said Winter.

Hauser coughed. Show him up to see Winter when he was not even shaved? And this was the tricky part: shaving round the master’s moustache. Hauser didn’t want to be doing that with an audience, and there was the chance that Winter would start talking; then anything could happen. Suppose his hand slipped and he made a cut? Then what would happen to his good job?

‘I’m deeply sorry to disturb you, Herr Winter,’ said the senior manager as he was shown into the room. This time the butler was with the visitor, instead of that scatterbrained little chambermaid. Hauser noticed that the butler’s fingers were marked with silver polish. That job should have been completed last night. These damned Austrians, thought Hauser, are all slackers. He wondered if Winter would notice.

‘It’s this business with Petzval,’ said the senior manager. He had big old-fashioned muttonchop whiskers in the style of the Emperor.

Winter nodded and tried not to show any particular concern.

‘I wouldn’t have disturbed you, but the messenger from Count Kupka said you should be told immediately…. I felt I should come myself.’

‘Yes, but what is it?’ said Winter testily.

‘He died by his own hand,’ said the senior manager. ‘The messenger emphasized that there is no question of foul play. He made that point most strongly.’

‘Suicide. Well, I’m damned,’ said Winter. ‘Did he leave a note?’ He held his breath.

‘A note, Herr Direktor?’ said the old man anxiously, wondering if Winter was referring to a promissory note or some other such valuable or negotiable certificate. And then, understanding what Winter meant, he said brightly, ‘Oh, a suicide note. No, Herr Direktor, nothing of that sort.’

Winter tried not to show his relief. ‘You did right,’ he said. He felt sick, and his face was flushed. He knew only too well what could happen when things like this went wrong.

‘Thank you, Herr Direktor. Of course I went immediately to the records to make sure the bank’s funds were not in jeopardy.’

‘And what is the position?’ asked Winter, wiping the last traces of soap from his face while looking in the mirror. He was relieved to notice that he looked as cool and calm as he always contrived when with his employees.

‘It is my understanding, Herr Winter, that, while the death of the debtor irrevocably puts the surety wholly into the possession of the nominated beneficiary, the bank’s obligation ends on the death of the other party.’

‘And how much of the loan has been paid to Petzval so far?’

‘He had a twenty-crown gold piece on signature, Herr Direktor. As is the usual custom at the bank.’

‘So this small tract of land on the Obersalzberg has cost us no more than twenty crowns?’

‘The money was to be paid in ten instalments….’

‘Never mind that,’ said Winter. ‘There was no message from Count Kupka?’

‘He said I was to give you his congratulations, Herr Winter. I imagine that…’

‘The baby,’ supplied Winter, although he knew that Count Kupka did not send congratulations about the birth of babies. Count Kupka obviously knew everything that happened in Vienna. Sometimes perhaps he knew before it happened.

‘My darling!’ said Winter. ‘Forgive me for not being here earlier.’ He kissed her and glanced round the room. He hated hospitals, with their pungent smells of ether and disinfectant. Insisting that his wife go into a hospital instead of having the baby at home was another grudge he had against Professor Schneider. ‘It’s been the most difficult of days for me,’ said Winter.

‘Harry! You poor darling!’ his wife cooed mockingly. She looked lovely when she laughed. Even in hospital, with her long fair hair on her shoulders instead of arranged high upon her head the way her personal maid did it, she was the most beautiful woman he’d ever seen. Her determined jaw and high cheekbones and her tall elegance seemed so American to him that he never got used to the idea that this energetic creature was his wife.

Winter flushed. ‘I’m sorry, darling. I didn’t mean that. Obviously you’ve had a terrible time, too.’

She smiled at his discomfort. It was not easy to disconcert him. ‘I have not had a terrible time, Harry. I’ve had a son.’

Winter glanced at the baby in the cot. ‘I wanted to be here sooner, but there was a complication at the bank this morning. The senior manager came to talk to me while I was shaving. At home, while I was shaving! One of our clients died…. It was suicide.’

‘Oh, how terrible, Harry. Is it someone I know?’

‘A Jew named Petzval. To tell you the truth, I think the fellow was up to no good. The secret police have been interested in him for some time. He might have been a member of one of these terrorist groups.’

‘How do you come to have dealings with such people, darling?’ She lolled her head back and was glazy-eyed. It was, of course, the after effects of the anaesthetic. The nurse had said she was still weak.

‘It was one of the junior managers who dealt with him. Some of them have no judgement at all.’

‘Suicide. Poor tormented soul,’ said Veronica.

Winter watched her cross herself and then glance at the carved crucifix above her bed. He hoped that she was not about to become a Roman Catholic or some sort of religious fanatic. Winter had quite enough to contend with already without a wife going to Mass at the crack of dawn each day. He dismissed the idea. Veronica was not the type; if Veronica became a convert, she was more likely to be a convert to Freud and his absurd psychology. She’d already been to some of Freud’s lectures and refused to laugh at Winter’s jokes about the man’s ideas. ‘It’s a good thing you’re not running the bank, my dearest Veronica. You’d be giving the cash away to any bare-arsed beggar who arrived with a hard-luck story.’ He moved a basket of flowers from a chair – the room was filled with flowers – and noticed from the card that the employees of the Berlin bank had sent them. He sat down.

‘I want to call him Paul,’ said his wife. ‘Do you hate the name Paul?’

‘No, it’s a fine name. But I thought you’d want to name him after your father.’

‘Peter and Paul, darling. Don’t you see how lovely it will be to have two sons named Peter and Paul?’

‘Have you been saving up this idea ever since our son Peter Harald was born, more than three years ago?’

She smiled and stretched her long legs down in the bedclothes. She’d chosen two names her American parents would find equally acceptable. She wondered if Harry realized that. He probably did; Harry Winter was very sharp when it came to people and their motives.

‘All that time?’ said Winter. He laughed. ‘What a mad Yankee wife I have.’

‘You are pleased, Harry? Say you’re pleased.’

‘Of course I am.’

‘Then go and look at him, Harry. Pick him up and bring him to me.’

Winter looked over his shoulder hoping that the nun would return, but there was no sign of her. She was obviously giving them a chance for privacy. Awkwardly he picked up his newly born son. ‘Hello, Paul,’ he said. ‘I have a present for you, child of the new century.’ He was a pudgy little fellow with a screwed-up face that seemed to scowl. But the baby’s eyes were Veronica’s: smoky-grey eyes that never did reveal her innermost thoughts. Winter put the baby back into the cot.

‘Do you really, Harry? How wonderful you are. What is it, darling? Let me see what it is.’

‘It’s a plot of land,’ said Winter. ‘A small piece of hillside on the Obersalzberg.’

‘A plot of land? Where’s Obersalzberg?’

‘Bavaria, Germany, the very south. It’s the sort of place where a man could build himself a comfortable shooting lodge. A place a man could go when he wants to get away from the world.’

‘A plot of land on the Obersalzberg. Harry! You still surprise me, after all this time we’ve been married.’ Through the haze of the ether that was still making her mind reel, she wondered if that represented some deep-felt desire of her husband. Did he yearn to go somewhere and get away from the world? He already had that beastly girl Martha to go to. What else did he want?

‘What’s wrong?’ said Winter.

‘Nothing, darling. But it’s a strange present to give a newborn baby, isn’t it?’

‘It’s good land: a fine place with a view of the mountains. A place for a man to think his own thoughts and be his own master.’ He looked at the baby. It was happier now and managed a smile.

1906

‘The sort of thing they’re told at school’

‘You have two delightful little boys, Veronica,’ said her father. He watched through the window of the morning room as the solemn ten-year-old Peter pushed his radiantly joyful little blond brother across the lawn on a toy horse. The children were in the private gardens of a big house in London’s Belgravia. It was a glorious summer’s day, and London was at its shining best. An old gardener scythed the bright-green grass to make scallop patterns across the lawn. The scent of newly cut grass hung heavily in the still air and made little Pauli’s eyes red and weepy. Cyrus sniffed contentedly. Their English friends urged them to come to London in ‘the season’, but the Rensselaers preferred to cross the Atlantic at this time of year, when the seas were calmer. ‘No matter what I’m inclined to say about that rascally husband of yours, at least he’s given you two fine boys.’

‘Now, now, Papa,’ said Veronica mildly, ‘let’s not go through all that again.’ She was wearing a long ‘tea gown’ of blue chiffon with net over darker-blue satin. Such afternoon gowns gave her a few hours’ escape from the tight corsets that fashion forced her into for most of the day. It was a lovely, loose, flouncy creation that made her feel young and beautiful and able even to take on her parents. She pulled the trailing hem of it close and admired it.

‘She’s given Harry two fine boys,’ Mrs Rensselaer scoffed. ‘Isn’t it just like a man to put it the wrong way around? Who endured that dreadful hospital in Vienna, when there was a bedroom and our own doctor waiting for her in New York City?’ They were getting at her again, but she was used to it by now. She noticed how much stronger her mother’s high-pitched Yankee twang sounded compared with her father’s softly accented low voice. She noticed all the accents much more now that her life was spent amongst Germans. She wondered if her spoken English had now acquired some sort of German edge to it. Her parents had never mentioned it, and she knew better than to ask them.

‘I couldn’t have come home to have the baby, Mother. You know I couldn’t.’ She suppressed a sigh. For six years they’d nursed this resentment, and still it persisted.