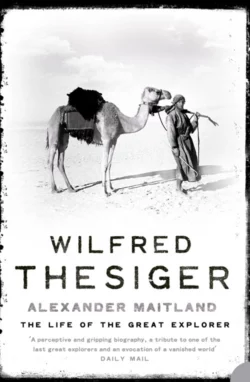

Wilfred Thesiger: The Life of the Great Explorer

Alexander Maitland

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1318.90 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Wilfred Thesiger, the last of the great gentlemen explorer-adventurers, became a legend in his own lifetime. This authorised biography by a longstanding friend and associate delves into his little-known character and motivations, as well as recounting the details of his extraordinary life.Wilfred Thesiger, the great explorer-adventurer and author of ‘Arabian Sands’ and ‘The Marsh Arabs’, and one work of autobiography ‘The Life of my Choice’, became a legend in his own lifetime, but his character and motivations have remained an intriguing enigma.In this authorised biography – written with Thesiger’s support before he died in 2003 and with unique access to the rich Thesiger archive – Alexander Maitland investigates this fascinating figure’s family influences, his wartime experiences, his philosophy as a hunter and conservationist, his writing and photography, his friendships with Arabs and Africans amongst whom he lived, and his now-acknowledged homosexuality.