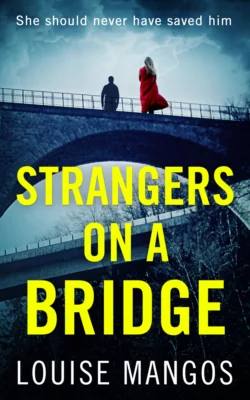

Strangers on a Bridge: A gripping debut psychological thriller!

Louise Mangos

She should never have saved him. When Alice Reed goes on her regular morning jog in the peaceful Swiss Alps, she doesn’t expect to save a man from suicide. But she does. And it is her first mistake.Adamant they have an instant connection, Manfred’s charming exterior grows darker and his obsession with Alice grows stronger.In a country far from home, where the police don’t believe her, the locals don’t trust her and even her husband questions the truth about Manfred, Alice has nowhere to turn.To what lengths will Alice go to protect herself and her family?Perfect for fans of I See You, Friend Request and Apple Tree Yard. Praise for Strangers on a Bridge‘As well-plotted and high-anxiety-inducing as any Hitchcock flick. 5 stars.’‘GREAT read, fast, with a number of twists and turns that you don't see coming!’ Janice Lombardo‘a really enjoyable read’‘outstanding’‘a truly impressive, accomplished debut novel’‘a brilliant thriller’‘Obsession, suspense and twists… what more do you need? Fantastic debut .’

Strangers on a Bridge

LOUISE MANGOS

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Louise Mangos 2018

Louise Mangos asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

E-book Edition © August 2018 ISBN: 9780008287948

Version: 2018-05-23

For Chris, for always believing in me

Table of Contents

Cover (#u1ddac396-c16b-56a4-806f-4a144991c34e)

Title Page (#u9fea0d7a-f24f-5549-962b-cc8699e6bb9d)

Copyright (#u6e9fd9d9-0217-5982-8095-92883b2eb0eb)

Dedication (#u0467ca49-a641-55d0-92b8-e52e0f1cf5c0)

Chapter One (#u08354106-3312-5591-9d28-a7ffa2a7daf9)

Chapter Two (#ub6004b81-ba58-5ba6-b0a5-2a2ecd908c42)

Chapter Three (#u71774db4-3387-55a2-a51c-36d9a00b9413)

Chapter Four (#u5684f41f-6610-55d1-ab00-e0ebd8a24a6c)

Chapter Five (#uf2e67073-3275-534c-8906-2a60bad6a3ac)

Chapter Six (#u29f68ab6-ec7e-5947-bf17-df272d1c12f8)

Chapter Seven (#uab1d99d1-7c72-5eeb-8454-eb9a7432b346)

Chapter Eight (#ue8c377fb-e188-552c-9782-b464781304a3)

Chapter Nine (#uee13d5d8-4fb3-5bcc-b1a3-683324550370)

Chapter Ten (#u741b893c-1efc-5eda-9262-162633b46eb8)

Chapter Eleven (#u349f755c-973b-5e22-915b-b9c5292c0a98)

Chapter Twelve (#u00a2652b-5bb1-54b7-8628-748fba371365)

Chapter Thirteen (#u190bfd98-07bb-520c-b863-d22294fe6d18)

Chapter Fourteen (#u37fc9ce1-ecfa-52fb-a6d8-9f235781997d)

Chapter Fifteen (#u843aa356-4e78-5508-b71a-7eaf13f448b5)

Chapter Sixteen (#u6cf98f70-dbd2-5ac9-95b9-98013de4f616)

Chapter Seventeen (#u53cbe210-eeed-5f20-ac81-99002b82fbec)

Chapter Eighteen (#u938aeedf-a5cb-51a3-8374-40f4c86d40a8)

Chapter Nineteen (#ua83ff71a-1de3-57c2-81b3-41c0d0bc175b)

Chapter Twenty (#ub7189386-400c-51dc-b0e8-8e7c0cd5da69)

Chapter Twenty-One (#u86e42866-1d02-5f7b-8b33-dd1f1cda03e0)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#ub3454bf0-edf7-5c02-a4f3-b6b150b505d0)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#ubfb99fe7-ba5f-570c-9251-7cd56a441358)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#ua07713df-c094-5f06-b3b5-782e9a28dcdd)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#u6f0ede81-13a1-5efd-a362-1863f59f41cb)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#u319b3147-4579-5e51-a61d-9d54cedf72d1)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#uda2b5fdb-e0bf-5c73-8f8a-14259cf2d4c3)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#udb575060-7c40-586c-be24-0810c45e80b1)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#u1521dbbc-bdf9-563d-b319-5ddece1e8f80)

Chapter Thirty (#u4fdb557e-5120-594a-aeb1-4ad503bad97b)

Chapter Thirty-One (#uf00a5277-6e7b-5da1-ad7e-83311840ca76)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#u9f2f034c-136c-5e30-80ff-a279e872bc66)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#ue6809f53-2e63-575a-8408-b5afb67e1356)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#u3a09f9c6-d4c4-5d3d-87db-9515f611e281)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#u08126417-953f-57e0-bf6c-eb3cd04c8575)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#u3f6216ed-c770-5da3-833b-49fe30577896)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#u4dfe79a0-e0c2-5f43-90b3-288996621cc6)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#u1fa47325-4d0c-5cc4-92f2-b5ccb1cd21f8)

Chapter Thirty-Nine (#u6afd9b3c-6b27-5766-9f4b-f3e1b94cd260)

Chapter Forty (#u8e083c9a-20b3-58e8-827b-e0f43d085715)

Chapter Forty-One (#ue44ef3fc-7dd1-5590-a5b1-4e98f828434c)

Chapter Forty-Two (#u57884dcd-67aa-5b10-a677-6ac454bcfd1d)

Chapter Forty-Three (#u21c87fa9-0eed-5d50-a50c-71dc7d00b169)

Chapter Forty-Four (#uc02eb09c-05c4-552c-891f-1ae9db1b6b09)

Chapter Forty-Five (#ubd03e327-6238-5465-8fa5-38a56fedbc69)

Chapter Forty-Six (#uec2c0cea-77b1-5896-bd78-fdfd8ae01a36)

Chapter Forty-Seven (#ud2959e43-c5c3-514d-bfa7-8287ae8556d8)

Chapter Forty-Eight (#udd4b26b0-6ddb-5e72-b77c-d7d316f709dd)

Chapter Forty-Nine (#u5b1fcd80-d0d3-5aa9-adb5-7691d2d3fbe7)

Chapter Fifty (#ub05c13c8-5e56-56e1-8094-139ceaf59b11)

Chapter Fifty-One (#uab478a96-5fbe-504b-a18b-f0a97c5d1e9f)

Chapter Fifty-Two (#uba984f04-fe64-5059-bb39-212e3513a637)

Chapter Fifty-Three (#u5f4cd295-35fb-57f1-89c2-ae5092a44ea1)

Chapter Fifty-Four (#u2b6fde72-3c6b-5682-9248-2ae65a075c47)

Chapter Fifty-Five (#u54e402ed-2a4f-52c1-a425-5a90a3d664d0)

Chapter Fifty-Six (#u529d1f3a-9736-57c6-baeb-c54b8f18ed74)

Chapter Fifty-Seven (#u9b2ec18a-baf9-5358-bff7-1dae732a0c70)

Chapter Fifty-Eight (#ub366ae0e-9c0a-5961-b77a-c116d4b654a0)

Chapter Fifty-Nine (#u5a83f897-a28e-5ae6-9841-ba2ddc1ada03)

Chapter Sixty (#u26ea7720-b523-5afa-9fbf-15ba90b798c3)

Chapter Sixty-One (#u5377c16b-3d80-5e4a-aada-1f37f1878d74)

Chapter Sixty-Two (#u3fdeb878-c608-5ed7-a6a1-b7fec8f47cbb)

Chapter Sixty-Three (#u4f045ef3-9c66-51e9-8bb4-3b48e7a2621f)

Chapter Sixty-Four (#ude425ae7-7489-544d-8c2f-cd1369404818)

Chapter Sixty-Five (#u5f4f18d6-f000-51fb-8580-cd1f48ecd8b2)

Chapter Sixty-Six (#u65d41540-17b3-5084-89ad-b2fdf5d027ba)

Chapter Sixty-Seven (#u98a4552b-f2c4-5660-9d15-5c6f033c4385)

Chapter Sixty-Eight (#u23aeaaaf-77a1-5d68-988e-922fa2175568)

Chapter Sixty-Nine (#uc8ef884a-26e7-544f-a8bb-53a70a596aa1)

Chapter Seventy (#u996df417-093c-5b41-b24c-e1f55935790a)

A Letter From The Author (#uaf5c7458-40f1-5e69-be65-322555900a49)

Acknowledgements (#u45cc9756-0bac-5dae-9f7c-b02fd67f0152)

Keep Reading … (#udb0cde5c-bcb9-55e7-8109-0d5a4764e4e0)

About the Author (#u7b9c5ac0-ba7b-568a-9120-9534a11ef4c1)

About the Publisher (#u3acafe82-923e-5343-81b6-af931a54e2bb)

Chapter One (#u5de377ad-5b0e-55a8-9ca7-822d3683bbba)

APRIL

I wouldn’t normally exercise on the weekend, but several days of continuous spring rain had hampered my attempts to run by the Aegerisee near our home during the week. The lake had brimmed over onto my regular running paths, turbid waters frothy with alpine meltwater. The sun came out that morning, accompanied by a cloudless blue sky I wanted to dive into. Simon knew I was chomping at the bit. He let me go, encouraging me to run for everyone’s peace of mind. He would go cycling later with a group of friends when I returned home for domestic duties.

I chose a woodland track from the lowlands near the town of Baar, and planned to run up through the Lorze Gorge beside the river, continuing along the valley to home. A local bus dropped me at the turnoff to the narrow limestone canyon, and I broke into a loping jog along the gravel lane, which dwindled to a packed earthen trail. Sunlight winked through trees fluorescent with new leaf shoots, and the forest canopy at this time of day shaded much of the track. The swollen river gushed at my side. Branches still dripped from days of dampness as the sun dried out the woodlands. I lengthened my stride and breathed in the metallic aroma of sprouting wild garlic. The mundane troubles of juggling family time dissipated, and as I settled into my metronome rhythm, a feeling of peacefulness ensued.

The sun warmed my shoulders as I ran out from the shade of the forest. I focused on a small pine tree growing comically out of the mossy roof shingles of the old Tobel Bridge. Above me, two more bridges connected the widening funnel of the Lorze Gorge at increasingly higher levels, resembling an Escher painting.

Before I entered the dim tunnel of the wooden bridge, I glanced upwards. A flash of movement caught my eye. My glance slid away, and darted back.

A figure stood on the edge of the upper bridge.

In a split second my brain registered the person’s stance. I sucked in my breath, squinting to be sure I had seen correctly at such a distance.

Oh, no. Don’t. Please, don’t.

The figure stood midway between two of the immense concrete pillars rising out of the chasm, his fists clutching the handrail. His body swayed slightly as he looked out across the expanse to the other side of the gorge, the river roaring its white noise hundreds of feet below him. Birdsong trilled near me on the trail, strangely out of place in this alarming situation.

At first I was incredulous. How ridiculous to think this person was going to jump. But that body language, a certain hollowed stiffness to his shoulders and chest, even from a distance, radiated doom. Unsure how to react, but sure I didn’t want to observe the worst, I slowed my pace to a walk, and finally stopped.

‘Haallo!’ I yelled over the noise of the river.

My voice took some time to reach him, the echo bouncing back and forth between the canyon walls. Seconds later his head jolted, awoken from his reverie.

‘Hey! Hallo!’ I called again, holding my arm out straight, palm raised like a marshal ordering traffic to halt at an intersection.

I backtracked a few metres on the trail, away from the shadow of the covered bridge, so he could see me more clearly. A path wove up through the woods on the right, connecting the valley to the route higher up. I abandoned my initial course and ran up the steep slope, having lost sight of the man somewhere above me. At the top I turned onto the pavement and hurried towards the main road onto the bridge, gulping painful breaths of chilly air. My heart pounded with panic and the effort of running up the hill.

The man had been out of my sight for more than a few minutes. I dreaded what I might find on my arrival, scenarios crowding in my mind, along with thoughts of how I might help this person. As I strode onto the bridge, I saw with relief he was still there on the pavement. I was now level with him, and no longer had to strain my neck looking upwards. Fear kept my eyes connected to the lone figure as I approached. If I looked away for even a second, he might leap stealthily over the edge. Holding my gaze on him would hopefully secure him to the bridge.

‘Hallo…’ I called more softly, my voice drowned by the sound of the rushing water in the Lorze below. I walked steadily along the pavement towards him. Despite my proximity, this time he didn’t seem to have heard me.

‘Grüezi, hallo,’ I said again.

With a flick of his head, he leaned back again, bent his knees, and looked ahead.

‘No!’ The gunshot abruptness of my shout broke his concentration. My voice ricocheted off the concrete wall of the bridge. He stopped mid-sway, eyes wide.

My stomach clenched involuntarily as I glanced down into the gorge, when moments before I had been staring up out of it. I felt foolish, not knowing what to say. It seemed like a different world up here. As I approached within talking distance, I greeted him in my broken German, still breathing heavily.

‘Um, good morning… Beautiful, hey?’ I swept my arm about me.

What a stupid thing to say. My voice sounded different without the echo of space between us. The words sounded so absurd, and a nervous laugh escaped before I could stop it.

He looked at me angrily, but remained silent, perhaps vaguely surprised that someone had addressed him in a foreign language. Or surprised anyone had talked to him at all in this country where complete strangers rarely struck up a conversation beyond a cursory passing greeting. His cheeks flushed with indignation. I reeled at the wave of visual resentment. Then his eyes settled on my face, and his features softened.

‘Do you speak English?’ I asked. The man nodded; no smile, no greeting. He still leaned backwards, hands gripping the railing. Please. Don’t. Jump.

He was a little taller than me, and a few years my senior. Sweat glistened on his brow. His steel-grey hair was raked back on his head as though he had been running his fingers through it repeatedly. His coat flapped open to reveal a smart navy suit, Hugo Boss maybe, and I looked down to the pavement expecting to see a briefcase at his feet. He looked away. I desperately needed him to turn back, keep eye contact. My hand hovered in front of me, wanting to pull the invisible rope joining us.

‘I… I’m sorry, but I had this strange feeling you were considering jumping off the bridge.’ A nervous laugh bubbled again in my throat, and I hoped my assessment had been false.

‘I am,’ he said.

Chapter Two (#u5de377ad-5b0e-55a8-9ca7-822d3683bbba)

Immeasurable seconds of silence followed the man’s admission. My brain shut out external influences. A blink broke the rift in time. Sounds rushed back in – the swishing of an occasional passing vehicle, gushing water in the river below, the persistent tweeting of a bird, like the squeaky wheel of an old shopping trolley.

‘Now you’ve stopped me,’ he said. ‘This is not good. You should go away. Go away.’

But the daggers in his eyes had retracted. I held his gaze, trying not to blink for fear of losing the connection. Many clichés entered my head. In desperation I chose one to release the tension.

‘Can we talk? I know things must be bad. But maybe if you talk it through with someone…’

I shrugged, unsure how to continue. Perspiration cooled my body, and I shivered. Pulling the sleeves of my running shirt down to my wrists, I rubbed my upper arms. Wary of the abyss at my side, I took a step closer to the man. He didn’t speak, but stood upright, and raised his hand as though to push me away. He turned briefly to look into the depths of the gorge, and I grabbed his arm firmly below the elbow, gently applying pressure. His gaze at first fixed on the hand on his arm, then rose again to my face. He studied my furrowed brow, and the forced curve of my smile.

‘Please. Let’s talk,’ I said.

I had no magical formula for this, but I sensed my touch eased the tension in his body. My nails scraped the material of his coat as my grip on his arm tightened. He slumped down to sit on the pavement with his back to the bridge wall. I closed my eyes briefly and puffed air through my lips.

Step one achieved. No jump.

Traffic was sparse on a Sunday. One car slowed a little, but kept going. No one else was curious enough to stop. The regular swish and thump each time a vehicle drove over the concrete slabs echoed between the walls of the bridge. We must have looked like an odd pair. Me dressed in Lycra running pants and a bright-yellow running top, the man in his business attire, now looking a little dishevelled. The laces on his black brogues were undone. I stared at his feet, and wondered if he had intended to remove his shoes before he jumped.

‘Can I help?’ I asked, crouching down. The man looked at me imploringly, hands flopped over his knees. The strain of anguish had reddened the whites of his eyes, making his irises shine a striking green.

‘I don’t know,’ he said uncertainly.

‘Well, let’s start with your name,’ I said, as though addressing a small child.

‘Manfred,’ he said.

There was no movement towards the traditional Swiss handshake. Still squatting, pins and needles fizzed in my feet. I kept one arm across my thigh, the other balanced on fingertips against the pavement.

‘Mine’s Alice, and I’m sorry, I don’t speak very good German…’

‘It’s okay,’ he said. ‘I speak a little English.’

I snorted involuntarily. It was the standard I speak a little English introduction I had grown used to over the past few years living in Switzerland, usually made with very few grammatical mistakes. The tension broke, and relief flooded through me. He would not jump. I sensed my beatific smile softening my expression. Manfred looked into my eyes and held my gaze intently, absorbing the euphoria.

I turned to sit at his side, blood rushing back to my legs. His gaze followed my movement, a curious glint now in his eyes, and his lips parted slightly, revealing the costly perfection of Swiss orthodontics. Leaning back against the wall, the cold concrete pressed against my sweat-dampened running shirt. I extended my legs, thighs sucking up the chill of the pavement. Our elbows touched and he drew in his knees, preparing to stand. I laid my hand on his arm.

‘You must not do this thing. Please…’

He looked at me, tears pooling briefly before he swiped at his eyes with the back of one hand.

‘You stopped me.’

‘Yes, I stopped you. I don’t want you to jump, Manfred.’

‘You…’ He scrutinised me.

‘It’s messy,’ I said.

Manfred’s gaze travelled from my face, looking at the dishevelled hair I knew must be sprouting from its ponytail, down to my legs stretched in front of me.

‘Taking your life,’ I continued. ‘It’s messy. Not just the – you know…’ I made a rising and dipping movement with my hand. ‘Trust me, I’ve been there.’

‘You… wanted to jump?’ Curiosity animated Manfred’s voice.

‘Not jumping, no. God forbid. A failed attempt at overdose. A teenage stupidity after a heartbreak. But I wasn’t going anywhere on a dozen paracetamol.’

I’d never told Simon this, and I bit my lip at the admission. I remembered the ‘mess’ I had caused: a hysterical mother, a bruised oesophagus, a cough that lasted weeks after the stomach pump, embarrassing counselling that all boiled down to adolescent drama.

‘Whatever has happened to make you do this, people will always be sad. You will harm more individuals than yourself. Not just physically,’ I continued.

Manfred hissed briefly through his teeth. ‘Ja, guet,’ he said, the Swiss German ‘good’ drawn out to two syllables. Gu-weht. He stared at a point below my face. I knew he was watching the pulse tick at the base of my throat, the suprasternal notch. The place where Simon often placed his lips. I blushed, and zipped my running shirt up to the collar.

His gaze shifted back to my face. A slip of a smile, and then a frown.

‘I cannot live with myself any more. I cannot live with who I am, what I do. What I have done,’ he said.

The back of my neck tingled.

‘But it doesn’t solve the problem for other people,’ I interjected. ‘It creates more. There must be another way to work out your… your problems. Your life is precious. Your life is sacred and will be special to someone.’

His lips formed a small circle.

‘My life is…’

‘Precious. Valuable. Prized. A good thing, not to be thrown away,’ I reiterated.

He smiled tentatively, siphoning my relief, feeding on my compassion. I felt my euphoria returned to me, delivered on a platter of… what? Gratefulness? No, it was something else.

My mouth went dry.

Chapter Three (#u5de377ad-5b0e-55a8-9ca7-822d3683bbba)

He shifted his body. My hand moved on his arm as he lifted a finger to wipe the dampness from under his eye. I wanted to reach out and hold his hand, relieve his sadness. He reached into the breast pocket of his suit jacket and pulled out a pair of glasses. He pressed them onto his face, and the rectangular black rims gave him even more of an executive look. I wondered what dreadful mistake had led him to the bridge. The stereotype of a man on the brink of financial ruin.

‘We have to get you out of here,’ I said as I pushed myself off the pavement and knelt in front of him. ‘Did you drive here? Do you have a car nearby?’

He shook his head, and looked down to the pavement.

‘Do you have a phone on you? Is there someone we can call?’ I asked more gently.

As he gazed up at me without answering, I looked down at his feet. I tied his shoelaces, feeling his eyes on me as I performed this task, putting him back together. Rocking onto my heels, I reached towards his hand, and stood slowly. Manfred stared at my wrist, hypnotised by the contact. His hand, at first limp in mine, strengthened its hold. Pressing my lips together into a flat smile, I dipped my head in encouragement, and pulled him to his feet.

I felt like brushing the dust from his jacket, handing him his non-existent briefcase like the caring wife, and sending him on his way to his high-powered job at some investment bank. But I knew he wasn’t ready to be left on his own. I kept hold of his hand to encourage him along the pavement, if only to get him off the bridge. As we walked towards a distant bus stop, I relaxed as we left behind the chasm of this man’s destiny. Manfred seemed to realise this too, gazing up into the bright sky. I was unsure whether the dampness between our palms was mine, or his.

‘Where are you leading me? This was not my plan,’ he said.

‘It’s okay. You’ll be okay. Let’s go.’ I smiled again, encouragingly. ‘Will you come with me to the bus stop? I don’t think I should leave you alone, but are you okay with that?’

Manfred’s lips tightened into a line. I knew I should keep him talking. But what the hell do you say to someone who’s just tried to throw himself off a bridge?

I shivered now, both from my rapidly chilling body and the influence of the adrenalin wearing off. My upper chest whirred unhealthily, and I coughed.

‘Come!’ My tone was falsely boisterous, trying to convince a small child to share an unwanted excursion. ‘It’s not far to the bus. At least we can get out of this damned cold.’

Manfred frowned. In his smart suit and coat, he was unlikely to be feeling the deceptive spring chill with this blue sky and sunshine. Attempting to stop my trembling, I clenched my jaw, and had trouble speaking. It was hard to focus on the timetable once we reached the stop. The next bus to Zug was in over an hour’s time. I couldn’t wait that long. I’d freeze.

‘This way,’ I said as we crossed the road to check the timetable for the bus going the other way, back to Aegeri, towards home. Ten minutes. Thank God.

As we waited, our hands fell apart. I fiddled pointlessly with my ponytail, tucking wild scraps of hair behind my ears. I rubbed my arms, occupying my fingers, trying to forget the connection of our palms. There was a steel bench, but I chose not to sit on the cold metal. Manfred stood within a pace of me, moving with me when I walked to the other end of the shelter. I was tempted to sidle up to him, absorb his body warmth. I had to remind myself he was still a stranger, despite what we had been through moments before. Instead I leaned against the glass wall to shield myself from the wind. Having held his hand for so long, I almost regretted the rift, but detected the return of some confidence in his demeanour.

‘You’re cold,’ he said simply, but didn’t offer me his coat or his jacket. I wasn’t sure I would have taken it anyway. I wouldn’t have wanted to infuse the post-sport odour of my body into the lining of his Hugo Boss.

I recalled the executives at the advertising agency where I used to work in London. They’d never been part of the group of employees who sought out my psychological counselling in the HR department. My experience there had extended only to office arguments, secretaries complaining they had been treated unfairly, and personality assessments. Studying a potential suicide scenario in college was one thing. Being faced with a true-life victim was something else altogether.

I wished Simon were there to allay my uncertainty. Even the company of my chatty running partner, Kathy, would have been welcome. I imagined she would have made light of the situation, distracting Manfred with her chirpy Northern-English accent. I wanted so desperately to bring this man out of his despair.

The whining of a large diesel motor interrupted my thoughts. We climbed on the bus, Manfred now complying without resistance. I used the change in my money belt to purchase two tickets from the driver, strangely relieved I wouldn’t have to ask Manfred for money, and accompanied him to a seat near the middle.

As the bus pulled away and picked up speed, we gazed out of the window. The vehicle turned in a wide arc, up towards the next village, every metre taking us away from the bridge. On the last hairpin bend before the valley disappeared from view, Manfred looked briefly back in the direction of the gorge, and nodded once, almost imperceptibly. He turned back to stare at the road ahead, then surprised me out of my thoughts.

‘What are you going to do?’ he asked.

I honestly didn’t know. I was making this up as I went along.

‘I need to get a warm jacket or something,’ I said. ‘And I don’t think you should be on your own right now. We’ll decide what to do after I get myself sorted at home, pick up my handbag, keys and stuff. We can use my car. I need my phone and then we can decide, Mister… um… Manfred.’

He seemed to accept this short-term first step and drifted back to gazing out of the window. I did the same, chewing my lip. I was impatient to see Simon.

‘You live in Aegeri? You’re not a tourist?’ Manfred’s delayed curiosity further reinforced my relief. It was as though he had joined me on the bus and asked whether the seat next to me was free. A passenger making polite conversation.

‘My husband works for a small trading company whose financial offices are in South London. He was offered a posting at the head office in Zug a few years ago, so we moved out here. I’m afraid I haven’t learned much German since I’ve been here. We were supposed to be here for two years, but they asked him to stay.’

‘You like Switzerland?’ Manfred asked with an edge to his voice, something between confused pride and disdain. I wondered again what had brought him to the bridge. Perhaps a failing in the machine that yielded Swiss bureaucracy.

‘It’s a beautiful country. It took me a while to get used to your… customs. But I love the rural alpine contrast to the city. I used to work in human resources at a busy advertising company, so this is a different world.’

I gazed out of the window at newly budding cherry trees blurring past, among fields strewn with the last of the spring crocuses.

‘I think our language is difficult to learn for the Ausländer,’ he said.

‘It was hard for me at first,’ I admitted, recalling a misunderstanding with our local electrician. ‘Our family was considered somewhat of a novelty when we arrived in the village. I set up something I call the Chat Club, where mums of the boys’ friends could improve their English.’

‘You have good Dialekt. Easy to understand. Not like some American accents.’

‘Thank you. And I can tell you learned your English from a British teacher.’ I smiled, almost forgetting why we were there.

‘Switzerland is a multilingual nation. We have four official languages, but you will see, English will become our allgemeine language.’

‘It feels like the idea of a universal language is a long way from reaching our little village. I was hoping to learn some German in return for my teaching efforts,’ I continued. ‘But I was outnumbered. It never seemed to happen. My kids learned really quickly, though. Starting with some not-so-pretty language in the playground at school.’

‘Then they have learned two languages. High German in the classroom and Swiss German outside school,’ he said.

I nodded, and remembered when I heard Swiss German for the first time, a more guttural dialect with a sing-song lilt, interspersed with much throat clearing and chewing of vowels.

‘The language barrier was much more of a challenge for me. But the priority of the Chat Club is to practise speaking English. I barely have chance to improve my own German-language skills beyond sentences of greeting and consumer needs. My compulsion to help has not been reciprocated… returned.’

Heat rose to my face as I remembered the things I had done wrong at the beginning of our move to Switzerland, impeding my integration into the community. It had taken me a while to get my head round some of the country’s pedantic customs.

I realised I’d been blabbing to Manfred, overly enthusiastic as a result of this rare opportunity to speak to someone socially in my own language outside the family. I folded my hands in my lap and looked at the passing houses as we entered the outskirts of the Aegeri Valley. As the bus drove past some woodland, the sudden darkness revealed the image of our two faces in the window, heads bobbing in unison with the movement of the vehicle. Manfred continued to look at me. I swallowed, and pulled my gaze away from his reflection to the front of the bus.

What was I getting myself into now? I felt a little lost in this situation. But it would have been unthinkable for me to have ignored this man and run on ahead up the valley. He was hurting enough to have wanted to take his life. Here was a scenario I had been half-trained to deal with and, alien as it seemed, I would try my hardest to find the right solution.

‘End Station,’ announced the bus driver.

‘Final stop, our stop,’ I said, standing up. ‘I live just outside the village. It’s a pretty walk.’

Stepping from the bus, we headed away from the village centre, our increase in altitude affording an unimpeded view of the lake. Sunlight glinted off the water in shards.

‘This is one of Leon’s favourite views,’ I said as Manfred turned enquiringly. ‘My eldest son. He loves the view, but hates the fact that he has to walk to school every day.’

I was making light conversation, trying to separate Manfred’s thoughts from earlier events. He said nothing, and his silence after our conversation on the bus felt awkward.

‘It is incredibly beautiful,’ I reiterated, then changed the subject. ‘Do you live locally? Close by?’

He gave a slight shrug and a movement of his head that said neither yes nor no. His eyes, now clear and inquisitive, looked at the lake, and I could tell he was appreciating the view, as the ghost of a smile touched his mouth. I bit my lip and looked back towards the water.

When we arrived at the door of the old Zuger house of which our duplex apartment was a part, I hesitated. I knew the fundamental rule was not to leave Manfred alone, but I was cautious enough to not want this man inside my home. In the porch was a bench where the kids usually sat to take off their muddy boots or brush snow from them in winter.

‘I need to get a few things. Just wait here. Take a seat. I’ll be as quick as possible. I’ll be right back.’ I tried a cheerfulness that sounded empty. ‘Okay?’ I put my hand on his shoulder.

Manfred nodded uncertainly and sat on the bench. I could tell his confusion and confidence were fighting each other in waves. I took a breath, and knew I definitely wasn’t equipped for this. I hoped more than anything that Simon would be at home to support me, to talk to this stranger who I had accepted as some kind of personal responsibility. Together we would have a better chance of helping him.

But as I crossed the threshold to our apartment, I knew immediately no one was home.

Chapter Four (#u5de377ad-5b0e-55a8-9ca7-822d3683bbba)

The door was unlocked, as always, security considerations not a priority in our safe Swiss world. The place offered the kind of muffled stillness where motes of dust were the only sparking movement through the strips of midday sunlight now streaming down the hallway. No breathing bodies.

A hurried note scribbled on the back of an envelope told me Simon had departed on a bike ride with his mates. He had dropped the boys with friends of theirs before heading out. The spidery scribble indicated he was mildly pissed off I hadn’t been home when I said I would. My first reaction was guilt, then a flash of irritation as I imagined him hurrying the note, not stopping to consider I might have sustained an injury or had a problem on my run.

I unclipped my running belt and let it drop to the floor, prising off my running shoes. I was still cold, and wished I could stay in my warm, cosy house. I ran the tap at the kitchen sink and took several big gulps of water straight from the flowing spout to quench my thirst.

After grabbing a fleece jacket, I pulled the car keys off the hook. Picking up my mobile, I swore I wouldn’t run without it again, despite its bulk and fragility.

I stabbed Simon’s number on the keypad.

‘Come on, come on.’ The ringing tone went on and on, eventually switching to his voicemail.

‘Honey, please call me as soon as you get this message.’

I imagined Simon pushing his cadence to the maximum along some winding alpine road, changing positions in the peloton as his turn came to draft the others, phone ringing unheard in the tool pouch under his seat. Placing the mobile in my pocket, I leaned over to pull off my socks and slipped my slightly sore feet into a comfortable pair of pumps.

I was wary and didn’t want to taint my hands with a decision that might lead Manfred back down the path of self-destruction. I was no experienced psychologist, and had never really used my skills in the remedial sense. This man needed help I could not give. Above all, my lack of mastery of the language meant I didn’t have a great deal of confidence when it came to approaching anyone in authority on this matter. And it was Sunday, the obligatory day of rest. Along with washing-hanging and lawnmowing bans, the police were also entitled to a day off. They might not be around to save lost souls on bridges. I wasn’t sure who I would find to help.

I glanced in the hall mirror, registering my post-sport mussed look, and hurried down the stairs to the main door.

Manfred was still sitting on the bench with his head lowered, but his body language had changed. My mood brightened as I noticed the squaring of his shoulders, the set jaw, and his hair neatly combed. He was cleaning his glasses with a tissue pulled from a packet lying next to him on the bench. His head was no longer poised in despair, but in a position of concentration, performing the simple task with an air of purpose. I had been expecting more empty looks and the shell of a wretched soul. The change in these few minutes was remarkable. Humility and purpose were evident, and I smiled broadly at his return to life.

‘I cannot believe I am so dumm, so stupid,’ he said, continuing to carefully polish a lens. ‘What was I thinking?’

A huge wave of relief washed over me. Part of me still wanted to help, but part of me wanted to turn my back on this situation now I was home. I selfishly wanted my weekend back. I wanted a hot shower and a cup of tea. I wanted to make up for my absence from our family Sunday when everyone came home.

As Manfred stood up, on impulse I put my arms around him and hugged him.

‘Welcome back,’ I said with relief.

As I felt the pressure of his arms gently hugging me back, with his palms on my shoulder blades, a blush rose to my face. I cleared my throat and released him awkwardly.

‘Is there somewhere I can take you? Would you like to use my phone to call someone?’ I asked, reaching for the mobile in my pocket.

He shook his head slowly.

‘No, I’ve no one to call. I don’t know, but I think I’ll go home.’

‘Is there… someone at home who will help you?’

A muscle ticked above his jaw as he clenched his teeth and a small sigh escaped his lips.

‘No, actually. On second thoughts, perhaps that is not such a good idea.’

I began to feel awkward about Manfred being in such close proximity to the house. His case needed to be reported; he should talk to someone.

‘Will you drive with me in my car?’

He looked at me, green eyes shining behind his glasses, brows slightly raised in an expression of complete trust. He fell into step beside me as we walked to the garage where our Land Rover was parked. He waited while I started the car. After reversing out of the garage, I indicated he should get in.

‘It’s okay, you can leave the garage door open,’ I shouted through the open passenger window as he stood for a moment wondering what to do.

Manfred nodded once. He took off his coat and folded it carefully over his arm, then undid the middle button of his jacket before climbing into the car, as though sitting down to a meeting at a conference table. As I drove along our rough driveway, he glanced around the interior of the car, and I followed the direction of his scrutiny. A set of tangled headphones, an empty bottle of Rivella, one football shinpad and various sweet wrappers were scattered over and between the seats.

‘Bit of a state,’ I said. ‘Two boys. Untidy boys.’ Manfred nodded.

‘I have a boy,’ he said. Oh.

His expression revealed sadness, but not the despair I had seen on the bridge. I stared back at the road. He didn’t elaborate, maintained a steady composure. I wasn’t sure if I should ask something. I released the breath I had been holding.

‘We need to find you someone to talk to,’ I said tentatively. ‘If you don’t feel you can talk to anyone in your family, perhaps someone else, a doctor, a friend…?’

‘When my English will be better I can talk to you,’ Manfred stated.

The irony of the sudden grammatical error made me smile and without thinking I retorted, ‘You mean, when my English is better…’ I waved my hand apologetically as I realised how patronising I sounded, and when I looked at him, he was smiling. I wondered if he had made the mistake deliberately. He paused before saying:

‘Yes. Natürlich. Sorry.’

‘Where is home?’ I asked.

‘Home… was in the next canton, in Aargau. I don’t think I can stay there. My wife is not… with me. She… she died.’

‘Oh! I’m so sorry.’

‘That was long ago,’ he said with a matter-of-fact tone. ‘My… my sister now looks after my boy. He is a student. But I don’t have a very good relationship with my son.’ He hesitated. ‘They don’t expect me back. I have broken that bridge.’

I was momentarily confused.

‘Oh, you mean burned that bridge; that’s the saying in English.’

I wondered if he had left his sister and son a note. And I found it ironic that a bridge had found its way into the conversation. He needed professional help straight away. I was hoping not everything would be closed on a Sunday.

‘No, I will not stay there,’ he said again as I glanced at his face. ‘But it is okay, don’t worry. You are helping. Thank you, Alice.’

It felt strange to hear him say my name for the first time. My hands gripped the wheel a little harder.

In the neighbouring village, I pulled into a parking space in front of Aegeri Sports, where we hired the boys’ ski gear each winter.

‘Wait here. I’ll be a moment,’ I told Manfred as I climbed out of the car.

The tiny suboffice of the Zuger Polizei was situated between the sports shop and a tanning salon. But as this was Sunday, as expected, it was inevitably closed. The hours were marked on the police station’s door like a grocer’s: Monday, Wednesday and Friday afternoons between two and four, Saturday mornings from nine until eleven. It might as well have said Citizens of Switzerland: criminal activity and social needs should be limited to these times.

I glanced at Manfred, reflections of trees streaking light and dark across the windscreen, obscuring my view. He leaned forward, unsure what we were doing here as the police station’s sign wasn’t visible from where he sat. I looked away quickly, chewing my cheek. I realised I should have dialled 117 from home, but I hadn’t been confident enough to explain my situation in German to the emergency services.

Anxiety tumbled my gut. Mostly because of Manfred’s potential reaction if I turned him over to the police. I was sure he wouldn’t be happy about that. I resigned myself to driving him to the hospital twenty minutes away in the valley.

That would mean twenty more minutes in the car with him.

Chapter Five (#u5de377ad-5b0e-55a8-9ca7-822d3683bbba)

As I climbed back into the car Manfred looked at me curiously. I started the engine and drove off without telling him why we had stopped. He didn’t notice the sign for the police station as we pulled away.

‘Manfred, you really need to talk to a medical professional, a psychologist,’ I said.

‘But you are a mother too. You will know the problems families have. You will understand. I was serious before when I said I think you can help.’

‘Is this only to do with your family? Your late wife? Your son?’ I asked gently.

I’d crossed the line, asked the question that had been in my mind since I first saw him in his business suit on the bridge. Why would he be dressed like that on a Sunday?

‘There is a reason we met today, Alice. I realise that now. There is a reason fate chose you to save me on that bridge. We have a connection. I know you feel it.’

I forced my gaze forward for fear of giving a false message with my eyes.

‘I know you’d like to help,’ he said after a moment.

‘I can’t help you, Manfred. I’m not a doctor or a nurse or a person remotely qualified to help you in your situation,’ I lied. ‘I can barely help my own kids when their team loses a game of football.’

As the road curved down towards the valley, I shifted in my seat when I realised our journey would take us over the Tobel Bridge. At the next junction, I took the left fork without saying anything to Manfred, retracing our bus journey back through the other village, a minor detour from the main road to Zug. To avoid the place Manfred had stood and contemplated his demise only hours before. Despite seldom finding myself behind the wheel of our car, I felt I never wanted to set eyes on the Tobel Bridge again.

‘Manfred, you need to talk to someone in your own language. There will be people at the hospital who can help you deal with the conflict going on in your mind and your heart. I cannot help you. I cannot.’

‘You told me you’d thought about taking your life too, once. Do you think you would still do that if your husband and sons didn’t want you to be a part of their lives any more?’

‘No, of course not!’ I said spontaneously, thinking what the hell kind of question is that? ‘I’m not the same person I was when I was a teenager.’

‘But you don’t know until you’ve been there,’ said Manfred, looking away from me to the passing suburbs of Zug.

Why did I suddenly feel he had turned the tables, was interrogating me somehow? Testing me. Making me say things I couldn’t qualify. My agitation increased as I realised he must be playing mind games with himself after a decision he couldn’t unmake.

What would the scenario have been if I had arrived ten minutes later? I put my hand to my mouth.

Manfred put his hand on my arm, and my heart thumped.

‘It’s okay, Alice. It’s okay,’ he said, as though I was the one he had just rescued.

The clicking indicator echoed in the car as I turned towards the hospital. I shook my head, to try to shift the image of a body dressed in Hugo Boss, sprawled under the bridge, from my mind.

I drove past the visitors’ car park and drew up next to an ambulance near the entrance to the emergency unit. I undid my seatbelt and was about to open the door, but Manfred hadn’t moved.

‘Please do this for me, Manfred. Please.’

I felt like I was bargaining with him to humour me. I couldn’t help thinking I no longer had any control of this situation. He sighed, unclicked his seatbelt, opened the door and stood beside the car waiting for me as I took the key and grabbed my wallet from the console.

At the reception, the glass window framing the front desk displayed a disorganised array of notes. Post-its and mini-posters rendered the administrators almost invisible to visitors, furtively encouraging patients to take their emergencies elsewhere.

There was a row of plastic tube chairs lined up against the wall. The waiting area was empty.

‘I don’t need to be here, Alice,’ he said. ‘We’re wasting these hard-working nurses’ time.’

I rolled my eyes, something I did at least once every day with my kids.

‘Did you forget where we’ve just come from?’ I whispered.

His eyes widened, glistening behind his lenses, and his brows furled into an expression of hurt. I took his elbow as an apology and led him to one of the chairs, where he sat down and crossed an ankle over his knee.

The receptionist gave me the silent answer of a horseshoe smile when I asked if she spoke English. I sighed. I had no idea what the word for suicide was in German. I had visions of a macabre series of charades. I tried my halting German.

The nurse looked blankly at me until I mentioned the Töbelbrücke. At that point she meerkatted to attention with a sharp intake of breath. She knew the bridge. It was notorious.

‘This man needs a psychiatrist, a psychologist, someone to talk to.’

The nurse explained that psychiatric help wouldn’t be available on a Sunday, but she was now aware that Manfred genuinely needed care.

As he wasn’t willing to cooperate, she asked me to fill in some details on a form. She slapped a pen down on top of a clipboard, and slid it across the counter. I reluctantly pulled the board towards me. The pen in my hand hovered over the form, my mind in a jumble, trying to comprehend the German words.

‘What’s your name, Manfred? Your surname?’ I asked.

‘Sir…?’ Manfred immediately swapped his belligerence for confusion.

‘Your surname, your family name,’ I repeated.

‘Guggenbuhl,’ he said sullenly.

How the hell do I spell that?

‘I’m sorry,’ I explained to the nurse. ‘It’s difficult for me to do this, as it’s not my mother tongue… I don’t even know this man. Can you help him?’

She sighed, but to my relief took the clipboard away. She asked for my personal details in the event of a police follow-up. She looked at my details on the paper I pushed across the counter.

‘If you have a mobile number, can we have that too?’

I nodded, scribbled down the number, and I was suddenly free to go. The last of my charity had long since expired. I wanted to go home.

Manfred stood up as I made to leave, but I seated him emphatically with a downward motion of my hand, the mistress trying to regain control of her dog.

‘You’re in better hands now,’ I said sympathetically.

Manfred stared at my hands.

‘I think you do know me. You are the key. My Retterin. My saviour. You can help me,’ he said quietly.

‘Someone here can help you much more than I can, Manfred.’

He held out his palm, and I suddenly felt bad about leaving him. I hesitated and shook his hand. Since our hug in the porch outside our building, I wasn’t sure I should touch him again, not trusting either of our reactions.

The seal of a handshake put official finality on the departure. But as I was about to pull away, Manfred brought his other hand to the outside of mine.

‘You will understand, Alice.’

As he smiled at me with what I assumed was gratitude, a flush tingled at my throat.

The yawn of space that opened between us as I turned to go was both cleansing and disturbing. Manfred smiled resignedly at me from his chair as I backed out of the sliding doors of the emergency room.

I walked back to the car, wondering what Simon would think about my experience, but more than anything anticipating a cup of tea and a hot shower.

Scalding water pounded the back of my neck and shoulders. The crusted salt of dried sweat dissolved into the shower basin. I hung my head and let my arms flop, enjoying the release of tension, inhaling the whorls of steam rising up around me.

I wondered again what had driven Manfred to the point where he was ready to jump. I’d felt down at times. Dealing with the isolation of being an only child, that stupid mistake as a teenager when my attempted suicide was considered an attention-seeking exercise, a bout of postnatal blues, or the loneliness I’d felt when Simon started travelling, and the kids were still so young, and I had no one to talk to for weeks on end. But even under the worst of circumstances, such as those Manfred had hypothesised about, I couldn’t do it. Because of the shame, the selfishness. All those hurt and confused souls wondering if it was their fault. The mess I had tried to convey to Manfred he would leave behind. I couldn’t burden anybody with that. And jumping off that godforsaken bridge? It would be the worst possible scenario for me, with my inherent fear of heights. It was either the ultimate thrill or the ultimate nightmare. And neither was plausible in my world.

I closed my eyes, knowing I was wasting water, but unable to move from the ecstasy of cleansing. I smiled as I thought of Simon, who would soon be home from his ride. From the start we’d been the perfect fit, the perfect couple. Although we stood by our individual opinions, we both ultimately wished for the same things for the family, and were fulfilled by what life had to offer us. My forced independence in our foreign world had made our love stronger.

Simon would be preparing for another round of business trips over the next few months as his new project developed, but I felt balanced and content in my foreign space now. Although I thought I could relate to Manfred’s despair, I couldn’t think of anything that would drive Simon and me apart, and I couldn’t imagine what had happened within Manfred’s family to lead him to that bridge.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/louise-mangos/strangers-on-a-bridge-a-gripping-debut-psychological-thrille/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Louise Mangos

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 292.56 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: She should never have saved him. When Alice Reed goes on her regular morning jog in the peaceful Swiss Alps, she doesn’t expect to save a man from suicide. But she does. And it is her first mistake.Adamant they have an instant connection, Manfred’s charming exterior grows darker and his obsession with Alice grows stronger.In a country far from home, where the police don’t believe her, the locals don’t trust her and even her husband questions the truth about Manfred, Alice has nowhere to turn.To what lengths will Alice go to protect herself and her family?Perfect for fans of I See You, Friend Request and Apple Tree Yard. Praise for Strangers on a Bridge‘As well-plotted and high-anxiety-inducing as any Hitchcock flick. 5 stars.’‘GREAT read, fast, with a number of twists and turns that you don′t see coming!’ Janice Lombardo‘a really enjoyable read’‘outstanding’‘a truly impressive, accomplished debut novel’‘a brilliant thriller’‘Obsession, suspense and twists… what more do you need? Fantastic debut .’