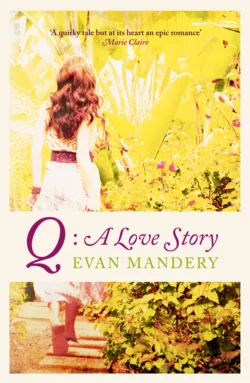

Q: A Love Story

Evan Mandery

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.26 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In a gripping tale of time travel and true love, a successful writer meets his future self, who advises him not to marry Q, the love of his life.Would you give up the love of your life on the advice of a stranger?A picturesque love story begins at the cinema when our hero – an unacclaimed writer, unorthodox professor and unmistakeable New Yorker – first meets Q, his one everlasting love. Over the following weeks, in the rowboats of Central Park, on the miniature golf courses of Lower Manhattan, under a pear tree in Q’s own inner-city Eden, their miraculous romance accelerates and blossoms.Nothing, it seems – not even the hostilities of Q’s father or the impending destruction of Q’s garden – can disturb the lovers, or obstruct their advancing wedding. They are destined to be together.Until one day a man claiming to be our hero’s future self tells him he must leave Q.In Q, Evan Mandery has fashioned an epic love story on quantum foundations. The novel wears its philosophical and narrative sophistication lightly: with exuberant, direct and witty prose, Mandery brings an essayist’s poise to this fabulous romance. And, finally, Q has an ending that will melt even the darkest heart.