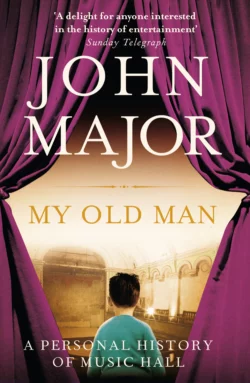

My Old Man: A Personal History of Music Hall

John Major

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Историческая литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 191.96 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The former Prime Minister takes a remarkable journey into his family past to tell the richly colourful story of the British music hall in this Theatre Book Prize-shotlisted history.Music hall was one of the glories of Victorian England. Sentimental, vulgar, class-conscious, but always patriotic and on the side of the underdog, it held a mirror to the audiences’ hopes and fears, and sometimes the general absurdity of life.Vast, smoke-filled auditoriums were packed night after night in nearly every town and city in Britain. The most popular performers, such as Marie Lloyd, Vesta Tilley and George Robey, were among the highest paid and most celebrated figures in the land.This was the world that John Major’s father Tom entered at the age of 21 as a comedian and singer. In My Old Man, the former prime minister uses his father’s story as a springboard for telling the entertaining history of the music hall, from its origins in Elizabethan times through to its heyday in the nineteenth century and eventual decline with the rise of radio and cinema in the twentieth century.Packed with colourful anecdotes about the great performers of the day, this warm-hearted history conjures up a lost age.