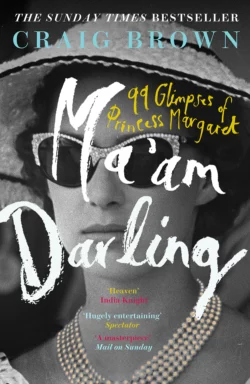

Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret

Craig Brown

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Юмор и сатира

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 625.04 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: WINNER OF THE SOUTH BANK SKY ARTS LITERATURE AWARD 2018A GUARDIAN BOOK OF THE YEAR • A TIMES BOOK OF THE YEAR • A SUNDAY TIMES BOOK OF THE YEAR • A DAILY MAIL BOOK OF THE YEAR‘A masterpiece’ Mail on Sunday‘I honked so loudly the man sitting next to me dropped his sandwich’ ObserverShe made John Lennon blush and Marlon Brando clam up. She cold-shouldered Princess Diana and humiliated Elizabeth Taylor.Andy Warhol photographed her. Jack Nicholson offered her cocaine. Gore Vidal revered her. John Fowles hoped to keep her as his sex-slave. Dudley Moore propositioned her. Francis Bacon heckled her. Peter Sellers was in love with her.For Pablo Picasso, she was the object of sexual fantasy. “If they knew what I had done in my dreams with your royal ladies” he confided to a friend, “they would take me to the Tower of London and chop off my head!”Princess Margaret aroused passion and indignation in equal measures. To her friends, she was witty and regal. To her enemies, she was rude and demanding.In her 1950’s heyday, she was seen as one of the most glamorous and desirable women in the world. By the time of her death, she had come to personify disappointment. One friend said he had never known an unhappier woman.The tale of Princess Margaret is pantomime as tragedy, and tragedy as pantomime. It is Cinderella in reverse: hope dashed, happiness mislaid, life mishandled.Combining interviews, parodies, dreams, parallel lives, diaries, announcements, lists, catalogues and essays, Ma’am Darling is a kaleidoscopic experiment in biography, and a witty meditation on fame and art, snobbery and deference, bohemia and high society.‘Brown has been our best parodist and satirist for decades now … Ma’am Darling is, as you would expect, very funny; also, full of quirky facts and genial footnotes. Brown has managed to ingest huge numbers of royal books and documents without losing either his judgment or his sanity. He adores the spectacle of human vanity’ Julian Barnes, Guardian