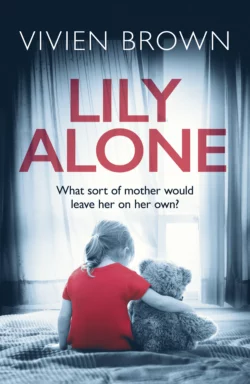

Lily Alone: A gripping and emotional drama

Vivien Brown

What sort of mother would leave her all alone… a gripping and heart-wrenching domestic drama that won’t let you go.Lily, who is almost three years old, wakes up alone at home with only her cuddly toy for company. She is afraid of the dark, can’t use the phone, and has been told never to open the door to strangers.But why is Lily alone and why isn’t there anyone who can help her? What about the lonely old woman in the flat below who wonders at the cries from the floor above? Or the grandmother who no longer sees Lily since her parents split up?All the while a young woman lies in a coma in hospital – no one knows her name or who she is, but in her silent dreams, a little girl is crying for her mummy… and for Lily, time is running out.

Copyright (#ulink_22232fdb-88d5-5b35-97df-44af7e4ebc10)

HarperImpulse

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperImpulse 2017

Copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) / Cover design by Books Uncovered

Vivien Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008252113

Ebook Edition © June 2017 ISBN: 9780008252120

Version: 2017-05-18

Dedication (#ulink_2fcc0d0b-9e6d-5584-955f-cd2318943030)

To Penny, who is almost the same age as Lily,

but will never be alone.

Contents

Cover (#u00c425cc-661a-5aeb-8368-a2a10796297c)

Title Page (#ud45443cf-caee-562a-ad15-c1ec5320d5b3)

Copyright (#uc82d08f6-f9bf-59a3-b034-d5e2b382be67)

Dedication (#u88d63dba-d3d7-5ba6-b621-26733f85f141)

Prologue (#u8a8171b9-764c-55e7-9240-bffa55992630)

Part One (#u599f1a4d-1dfa-5a69-a760-497c0001a4e0)

Chapter One (#ua60a5359-193b-5457-b104-86ad075760cc)

Chapter Two (#udaeaf8f0-782c-5332-b8b5-3ee032ff08a3)

Chapter Three (#u5014f319-98a1-570b-8e81-2fa384589382)

Chapter Four (#u71d18988-fe4f-5f08-900a-b671e80c2a59)

Chapter Five (#u8f3e0c6b-574c-5aea-9336-71668f73a6a3)

Chapter Six (#u4aa07657-559d-521a-be79-6f994515492d)

Chapter Seven (#u02d82014-bf96-5e04-aa9a-a65e47ff4f36)

Chapter Eight (#ua4f5aa2d-2e9e-54d7-b183-11ceafd400cc)

Chapter Nine (#ua45534a9-dcb3-5884-bb94-d57b49408a2c)

Chapter Ten (#uad423ac8-74f5-5d63-bc76-bb465cf841b0)

Chapter Eleven (#u63ae3be0-cbc9-595d-9bed-b003ce8840a0)

Chapter Twelve (#u1f915906-51d9-5b02-b0a1-5c7673251317)

Chapter Thirteen (#ue1b81a05-89ac-53bc-8fc8-47d98e995f26)

Part Two (#u9b446aa8-165d-53c3-b8a7-e1b4a6e1edfa)

Chapter Fourteen (#u951ca3a0-28d3-5c54-a2a0-28e13251ced6)

Chapter Fifteen (#u71f0ce69-3304-5733-a85a-ad7ab4f48cc6)

Chapter Sixteen (#u1291bd9b-b6dd-5ac3-abc4-9cfcd96aee2e)

Chapter Seventeen (#u86bc2f0c-5304-52b4-9551-540de2a79104)

Chapter Eighteen (#u806e4826-0f7c-5cdb-a446-2ddb7171bc95)

Chapter Nineteen (#ubd73bce7-5367-5fee-bb57-310e1b6d67d1)

Chapter Twenty (#ue8629ee1-8d30-5b44-a141-230ebaded5ce)

Chapter Twenty-One (#u7fde1b60-fe4d-598b-848b-b696a0b26d92)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#uf6dfbec9-3c05-5ea7-88c5-0908b88f7185)

Part Three (#ua3c07e56-9d4c-5e25-a9ce-5e9ec7cfe0ce)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#u83c3194c-f575-5f10-a69d-b876b572022c)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#ua3f00d40-f40a-5c9d-8d4b-1e0a40a37e16)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#u6a176468-b756-5d02-8488-ccffbf2ae7b3)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#ud74e159d-9707-5846-b139-7139c09a48e4)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#u0ca0b4ef-fd77-5f2f-bbdd-b224fc4a1121)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#ubc96c91a-1a5c-5fda-b6ab-ec2b2659264c)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#u7b97c33d-6402-57f7-8dcb-295122a984ca)

Chapter Thirty (#ud7d38336-5b9c-5b62-9674-00c271cf2655)

Chapter Thirty-One (#uc093a366-ae11-581b-8143-c41f9e622d70)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#u5b5cd79b-6a09-55fc-a178-3369b15701c3)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#u3ae583b5-2777-585b-8b95-39bba8b0194a)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#u6ee80bc0-abe7-5b39-b8b0-cd9497c656de)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#ub462c8e7-adc9-59d5-8688-df060336262b)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#uf4108f80-c553-5eec-8f36-e5437eb9c947)

Acknowledgements (#uf0c57c4c-b67d-5d5d-bfc3-35c067657033)

About the Author (#u64f4a5a1-a607-5572-a080-b120e31de678)

About the Publisher (#u5bf68029-2500-5a9b-be2c-31019e5f99f1)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_ba4378ec-95b6-540f-adff-769e3d6a9ace)

Ruby

There’s a face looking down at me. Big and blurry, not quite in focus. I close my eyes and open them again, slowly, but it’s still there. Go away. I don’t know who you are. Let me sleep. I need to sleep.

Other faces now, working their way into shot, waving about around the edges like the petals of a daisy, opening and closing, opening and closing. My back feels cold, and I’m lying on something hard. And wet. I don’t know how I got here. Or where here is.

‘It’s okay, sweetheart. Don’t try to move.’

Mike. Mike always calls me sweetheart. Calls everybody sweetheart. Is he here?

‘You’ve been in an accident. Just hold on there. The ambulance is on its way.’

It’s a woman now, bending down next to me. What does she mean, hold on? What am I supposed to hold on to? I try to reach for her hand, but mine won’t move. It just lies there, like a piece of dead meat. Disconnected.

The woman’s knees are bony, pressed against my side, and there’s water running off her mac and dripping onto my hand. I’m lying in the road. And it’s raining. How did I end up in the road? She touches my shoulder. Her face is white, really white, as if she’s had a shock; seen a ghost or something.

Why do I feel so cold? Did I forget to put the heating on? Where’s my duvet? I just want everyone to go away and leave me alone, so I can close my eyes and go back to sleep. But there’s so much noise. People talking, whispering, crying. Why is someone crying? Sirens now. Getting louder, closer.

And a minute later – or is it five? ten? – the thumping of a door. Two people in bright yellow jackets are squatting in front of me, touching me, talking to me, asking me my name. I stare at the yellow. It’s the same yellow as Lily’s new pyjamas, but without the rabbits. Lily likes rabbits. My stomach lurches. Lily. Where’s Lily?

‘Your name, sweetheart,’ one of them says again. ‘Can you tell us your name?’

I try to lift my head, to look for her. She should be here, with me, but she isn’t. My head falls back down, hard, as if I can’t hold its weight. Someone is clamping something around my neck now, and I can’t move any more. The sky is everywhere. It’s all I can see, like a thick grey blanket falling over me. I can feel the wetness at the back of my head, running down my neck, creeping inside my hood. It’s warm, sticky. Not like rain at all. Something – everything – hurts. Really hurts.

‘Lily …’ I say. ‘Lily …’

And then I’m gone.

PART ONE (#ulink_8a26db19-8759-53c6-96f8-6186519882d3)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_5e3930ff-d70a-5d3a-915e-607c5a0db224)

Archie was hungry. Lily let his wet ear slip out of her mouth. She rubbed a sweaty hand over her eyelids and yawned, cuddled Archie up tight to her chest, then threw the covers back and held him up at arm’s length, tugging his little knitted trousers off over his feet.

Archie should have pyjamas for when he went to bed. Or to wear in the daytime sometimes, when there was nothing special to get dressed for. Lily had been wearing hers all morning, and so had Mummy.

Lily’s pyjamas were yellow, with bunnies on, and yellow was her new favourite colour. When they got a garden of their own she would grow yellow daffodils, and have a real live bunny of her own too. Mummy had promised.

The curtains were half closed, but little shadows of light darted about like jumping frogs on the ceiling. There was a lot of noise outside. Loud noise. Lily didn’t like loud noise. When people shouted, or fireworks banged, or balloons popped. She hated those things. You had to close your eyes and put your hands over your ears when they happened. She didn’t want fireworks or balloons at her birthday party. Just presents. Mummy said she was going to be three. She’d held up her fingers to show Lily what three looked like. Baa baa black sheep. Three bags full. She’d like a bouncy castle too, at her party, but castles were very big and cost lots of money so she didn’t think Mummy would really get one. But maybe she’d get her a bunny, if they had a garden by then.

Out in the street, there was a wailing, screeching sound, like she imagined the big bad wolf would sound if he was very angry and coming after the pigs. Mummy had left one of the little windows open right up at the top, and the wind was blowing in, making the bottom of the curtain move. I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house down …

Lily remembered the story of the wolf and the pigs. One of the ladies at the nursery had read it to them, when they all sat in a circle before they went home, but Lily didn’t like it. She didn’t like the story, and she didn’t like the noise. She tried to cover her ears and pull the quilt up over her head all at the same time, making sure she hung on tightly to Archie to keep him safe, and to stop him from being scared.

The noise went away. She peeped cautiously over the top of the covers and, when she was sure there was no wolf, she settled Archie on the pillow beside her and sat up in bed. She’d only had a nap, not an all-night sleep, but her nappy felt heavy, and she was thirsty. She wanted some juice. Bena juice. That was her favourite, except maybe Coke, but she wasn’t allowed that very often. Only on special days. Lily didn’t think this was a special day.

Maybe Archie could have some juice too, as he’d been good. She yawned, and called out for Mummy, fiddling with a black thread that had come loose from Archie’s eye and was hanging down over his nose. Mummy would mend that, with something from her big red sewing tin that used to have biscuits in it, or with the glue that Lily wasn’t allowed to touch. Mummy was good at mending things. It saved buying new, she always said.

Lily waited but Mummy didn’t come, so she called again, louder this time.

Lily climbed out of bed, her foot springing onto the book she’d left open on the rug, flipping the pages over and making the spine snap shut. The baby in the flat upstairs was crying. It did that sometimes. Today it was doing it lots. It sounded sad, like Archie. Maybe it wanted some juice too. She walked over to the door, peered out into the empty hall, and called out again.

‘Mummy …’

But Mummy didn’t come. Nobody came.

*

Agnes Munro looked up from her crossword. There were sirens going off in the street again, the honking of horns, a motorcycle revving its engine and screeching off into the distance, probably bumping up and over the pavement in the process. That’s what they usually did when there was a jam.

That was the trouble with living in London. Even here, on the outskirts, it was too busy, too noisy. There was no real sense of community. Nobody seemed to care about anything much, let alone the state of the roads or trying to preserve a bit of peace and quiet. Always something going on, even at the weekend, and not always something good. What now? A broken-down bus, some impatient driver carelessly thumping his bonnet into somebody else’s boot, or yet another robbery on the high street?

She tried to push the sudden thought of her old home out of her mind and concentrate on the two final clues she’d been puzzling over for the last five minutes. Oh, how she hated leaving a crossword unfinished. In fact, she wouldn’t, couldn’t. If it took all day, she’d make sure she finished it somehow, but crosswords, like just about everything else, seemed to be taking her so much longer these days. Her body certainly wasn’t as fast or efficient as it used to be. The creaking in her knees as she moved told her that. Perhaps her mind was starting to go the same way. And those little empty white squares looked so forlorn, and so untidy.

She wondered if the dictionary might help, but it was in the bookcase under the window, out of reach. Smudge was dozing on her lap, twitching in his sleep, and she didn’t want to disturb him. She leant across, very carefully, to the small lace-covered table beside her, picked up her tea and took a warming sip, tapping her pen idly against the side of the china mug as she struggled with the letters of an anagram in her head.

Life had always been so peaceful before, when she’d lived in the old cottage. The home that they’d told her was too rundown, too big, too isolated now she was getting older. Much better here in town, they said, where they could keep an eye on her, where the shops were just a short walk away, where the buses ran right past the door. And a ground floor flat too. No stairs and so much easier for her to manage, especially with arthritis setting in with a vengeance, giving her painful, knobbly fingers and stiffening knees.

Downsizing. That’s what they had called it when the idea had first been mooted eighteen months ago. Her son William, and his ever-efficient wife. They had made it sound quite exciting back then, like a big adventure, something wonderful to be embraced and thankful for. Downsizing, indeed! Agnes could think of a better word, but she dared not say it out loud. They didn’t like it when she swore. Not that there was a ‘they’ any more. Now her daughter-in-law had gone – good riddance – and there was just William. She chuckled to herself. Just William. Wasn’t that the name of a naughty boy in some old children’s book?

Agnes gave up on the anagram. Her mind was too busy jumping about elsewhere. That was one of the hazards of living alone. Too much time to think, and nothing of any real importance to think about. Well, nothing she could do much about, anyway.

She finished her tea and tried to replace her empty mug on the table without moving Smudge, but the big grey cat woke up, stretched and jumped down, ambled over to his cat flap and let himself out into the communal hall with a clatter of rebounding plastic. He would sit for a while on the coir doormat outside her flat, preening, then wait at the front door of the block, as he always did, until one of the other residents, either coming in or going out, eventually let him through. Sometimes he would walk steadily up the three flights of stairs to the top of the building where he could sit and gaze out from the grimy windowsill on the landing at the birds twittering away, up high in the one and only tree. Agnes had followed him up all those stairs once, just to see where he went, but she’d had to stop and rest after each flight, and had needed some strong tea and a couple of paracetamol as soon as her aching joints had made it safely back down again.

She took off her reading glasses and tried to switch to the other pair she kept for distance, the two pairs dangling side by side from adjacent chains around her neck. The chains were tangled together today and it took her a few moments to unwind them. She muttered to herself and winced as she stood. Her knees were playing up again, as usual.

Going to the window, she lifted the edge of her newly washed nets, popped on the right specs and peered out into the street. Dull, grey, October drizzle, with another winter not far off. Traffic bumper to bumper, wipers swishing across grimy screens, the male drivers drumming their hands on their steering wheels, the women taking the opportunity to peer into mirrors and redo their make-up or neaten their hair. An ambulance was trying to make its way through. Was there really any need for the siren? Sometimes she thought the drivers just did it to make themselves feel important. It’s not as if it couldn’t be seen, what with the blue light and all the cars doing their best to mount the kerb and get out of its way. More cracks in the pavement! It’s a wonder more folk didn’t trip and sue the council for compensation.

From two floors above, she could hear that baby screaming again, probably woken up by the racket going on outside. She thought of going up there to complain, but she couldn’t face the stairs, and what good would it do, anyway? How could she tell a baby to be quiet, or expect its mother to make it? Babies couldn’t help it, could they? Crying came naturally to them. Their way of saying something was wrong. Perhaps she should try a bit of weeping and wailing and see if it helped. See if anyone came running to pander to her every whim, to make things right again. She smiled to herself. She was just being grouchy, that was all. Blame it on the knees. Silly old woman!

Ah, well. She might as well watch some telly now she was up and about. Her favourite antiques programme would be starting soon. The one where they found hidden treasures in people’s lofts. As if! All they’d found in hers when she moved was Donald’s old army pay book, some dressing-up clothes from William’s am-dram days, and a pile of dusty photos, mostly of people she didn’t even recognise, let alone remember.

Still, they might have some teapots on the programme today, if she was lucky. Agnes liked teapots. They were a passion of hers. Old ones, obviously, and some of the more unusual, novelty ones too. Not to use, of course. Oh, no, she had to admit that, being by herself so much of the time, a teabag dunked straight into a cup of hot water did the trick quite nicely these days. But there was something undeniably beautiful about teapots. To look at, and to touch. Such smooth shapes, such elegant spouts and handles. In fact, she’d built up quite a nice collection over the years, even if they were all boxed up in William’s garage now because she didn’t have the room.

She sighed. What was the use of thinking about all that stuff? Her life had changed, and she knew full well it was never going to change back again. At least having the telly on, perhaps a bit louder than necessary, might just help to drown out all the incessant noise.

*

The plane lurched as it hit yet another air pocket, knocking a passing stewardess, hip first, into the side of Patsy’s seat.

‘Sorry, Madam.’ The girl carried on up the aisle, totally unfazed, small uniformed hips wiggling easily from side to side. All in a day’s work, probably. Patsy closed her eyes, took a deep breath, and thanked God she didn’t have to do a job like that.

‘It’s just a bit of turbulence, sweetheart.’ Michael picked up Patsy’s hand and stroked it reassuringly, fingering the new diamond ring that sparkled under the overhead lights. The ring he had laughingly told her he still couldn’t quite get used to, even though he’d put it there himself, only two days before. ‘Nothing to worry about. We’ll be landing soon.’

Patsy smiled at him, trying really hard not to be sick. She was not a good air traveller, and if there was one thing guaranteed to put a man off for life, it was watching a girl being sick. She’d done it once, after a party. Vomited all over the front seat of some boy’s shiny new car. She could still remember the acid taste and the pervasive smell of it, clogging her nostrils, caked onto her dress and mixed into her hair, as it spewed out between her trembling fingers when she tried to hold it back. The huge dollops of it running down the upholstery and onto the rubber mat at her feet. And the look of utter horror on the boy’s face as he pulled over and stopped the engine and watched her lean out over the kerb, spilling the remaining contents of her alcohol-fuelled stomach all over the road. She could no longer remember his name, but she would never ever forget that face. Or that feeling.

Oh, no, if she was going to be sick, it had to be somewhere else, out of sight, away from Michael. She stood up, unsteadily. ‘Won’t be long,’ she said, slipping her hand out of his and edging into the aisle.

‘Seatbelt signs are on, Pats. Maybe you should stay here for now …’

But the loo was only a few feet away, and she needed privacy, some time alone before they landed. She shook her head, tried to smile, and stumbled into the cubicle, sliding the bolt across, and landing with a thump on top of the loo seat.

You’re going to have to get used to sick if you’re going to be a stepmum, she thought. And temper tantrums, and potties, and God knows what else. She bit down hard on her lip. She wanted to do this. Of course she did. For Michael. He’d already missed too big a chunk of Lily’s life. And that was mostly down to that vengeful ex of his. Since they’d been away, Ruby hadn’t even let him speak to his daughter on the phone, and they both felt sure that the little presents they’d so carefully chosen and posted to her had probably never been opened. Most women left alone with a child would be banging on the door of the Child Support Agency demanding what they felt they were due, but oh no, not Ruby. She wanted nothing from Michael. She’d made that abundantly clear. Not even if that meant Lily went without. Well, it couldn’t go on. As Michael had said, thumping his fist on the table in anger when yet another bank statement showed she had failed to cash any of his cheques, something definitely had to change.

Patsy closed her eyes and tried to picture the Ruby she’d met a couple of times, a while back, before Michael had made the decision to leave, but all she had seen then was a mouse of a girl utterly lacking in confidence, thrown unexpectedly into motherhood far too young and trying way too hard to be a grown-up. She had felt almost sorry for her back then. There was a flicker of guilt too, for her own part in what had happened. If she and Michael hadn’t met, hadn’t fallen in love, then maybe he would still be there now, with Ruby and his daughter. They may have been far from the perfect family, but they had been a family nonetheless. But then, nothing is ever quite as straightforward, or as one-sided, as it appears, is it? Michael may have been the one to cheat, the one to walk away, but …

Patsy had insisted from the start that he talk to her about it, about what his life with Ruby was like, so she could make up her own mind and understand just what she was getting herself involved in, what harm they might be causing if he was to walk away. She still found Michael’s reluctance tricky to deal with sometimes. It was as if he just wanted to bury his head in the sand and pretend Ruby didn’t exist, so she still didn’t know it all, and probably never would, but it seemed there was another side to Ruby. Since Michael had gradually filled in some of the blanks, the meek and mild person Patsy thought she had seen had morphed into someone far more fiery and unpredictable, and feeling sorry for her had become a whole lot harder.

Still, it was Lily who mattered now, much more than Ruby. Lily needed her daddy back in her life, and it was Lily they were coming home for.

She held her finger up and looked again at the sparkling new ring that still felt heavy and unfamiliar. It was beautiful, but it had to mean more than just a decoration, an extra glitzy jewel to add to her collection. It came with responsibilities, conditions that had so far been left largely unspoken but were nevertheless very real. No, it was up to her to support him, to help him fight to find a way back into Lily’s life, to show him she was up to the task. Motherhood, even just part time, was going to be a big thing, a major commitment, especially trying to mother someone else’s child, a constant reminder of the woman – no, the girl – who came before. She shivered, hugging her arms around herself, and tried to breathe slowly and calmly as the plane lurched menacingly beneath her.

Maybe they’d even have a baby of their own one day. Not for a year or two yet, obviously. Or more like five or six. She was still only twenty-seven, and she had her career to think of, after all. She certainly hadn’t reached the point where a career break, even of just a few months, could possibly work. It was a small company, still growing, and she wanted to grow with it. The board were counting on her to get this European project up and running. It was her big chance to prove herself. But one day, when she was ready, when the biological clock that people talked about started to tick – if it ever did – then maybe.

Getting to know Lily would be a start though, wouldn’t it? Like a practice run, to see if things worked out. But things had to work out, didn’t they? There was no other option. Not if she wanted to keep the ring on her finger, become Mrs Payne, keep Michael happy …

The plane tipped and jolted, suddenly bouncing her bottom up off the seat and depositing her back down again, hard. She only just had time to swivel round in the tiny space between the toilet and the basin and the door, press her hands hard against the wall and line her head up with the pan before she was violently sick. She looked down at the spatter of pale gloopy drops that had somehow bypassed the edge and splashed out onto the floor around her. She’d missed her new Jimmy Choos by a whisker.

Somehow, even that small piece of luck didn’t make her feel any better.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_4c4ca2bc-d764-5409-a3fb-fa6db1aa9a41)

Geraldine Payne stood among the crowds in the arrivals hall at Gatwick, watching the passengers as they trundled through the doors, sporting new suntans, pushing over-laden trolleys, carrying white plastic bags stuffed with cigarettes and booze, their clothes all crumpled from their flights.

Michael had called her before he boarded, told her that he and Patsy had something important to tell her just as soon as they got home, and would she mind coming to Gatwick to pick them up? Well, it could only be one of two things, couldn’t it? Either an engagement, or the girl was pregnant. Given the choice, and remembering what had happened the last time, she wasn’t at all sure which she should hope for. But Michael was a grown man and he wouldn’t thank her for voicing her opinions. She couldn’t tell him what to do any more. She’d tried that before, and look where it had got her.

She checked her watch again and compared it with the time on the arrivals board. This was the right flight, wasn’t it? Lisbon. Two forty-five. It had to be. Where were they? Too busy canoodling to get themselves out here on time, she shouldn’t wonder. Unless they’d been stopped by Customs, of course. The amount of bling that girl carted about on her wrists, and even round her ankles on occasion, they’d probably mistaken her for a jewel smuggler. Not the sort of girl he might have met had he stayed at the bank. A good, steady job he’d had there. None of this big contract, sweeping-himself-off-to-far-flung-corners-of-Europe stuff he’d got himself mixed up with these days. Too much risk, too much change, too much she didn’t understand. It wasn’t what Geraldine was used to at all. She knew she was a creature of habit, the sort of woman who liked to stick with what she knew. There was safety, and an element of comfort, in the familiar, wasn’t there? The everyday normality of life ticking along the way it always had. Ironing his work shirts, choosing the chops for his tea, the sound of his key turning in the lock at half past five …

But all of that was gone. Long gone. Things were different now, and likely to stay that way.

Where on earth were they? At these exorbitant airport prices, she had been hoping to get away with just an hour’s car parking, and more than half of that had gone already. She was a busy woman, with things to do. She had a shop to run, and it was Saturday, the busiest shopping day of the week. She never liked to leave Kerry in charge for any longer than necessary, and a whole afternoon felt like way too long. The girl meant well, and she was as honest as the day was long, but she didn’t have a lot going on between the ears. It would only take one wrong delivery or a dispute over change and she’d go to pieces.

Geraldine opened her bag and took out two of her migraine pills, the pink ones. The last two in the packet. She could feel one of her heads coming on, and there was still the drive back home to have to cope with. She didn’t have the time to be ill. At sixty-two, if her life had turned out differently and she didn’t have to constantly battle on with everything alone, she’d have been seriously thinking about retiring by now. But there was the house to manage, and a garden just a little too big for her to tackle with any real success, and the business to keep afloat. And now Michael was coming back after four months away and with heaven knows what bombshell about to be dropped at her feet. Sometimes all she wanted to do was bury herself under a duvet and sleep for a week. The trouble was, she knew it would all still be there waiting for her when she woke up again.

She thought about seeking out a cup of tea. There was nothing quite like a spot of tea and sympathy, even if all the sympathy she could muster was for herself, but they’d be here any minute now and she didn’t want to miss them. Airport tea would probably be horribly expensive anyhow, or just plain horrible. She tipped the pills to the back of her throat without the benefit of any liquid to help them on their way, and swallowed, still feeling the little dry lump in her throat after they’d fought their way down. Bloody Ken. Why did he have to go and die, just when life was finally looking like it might turn out okay after all? And why did she still feel so angry with him? It’s not as if he’d done it on purpose.

She shook the thoughts away and rummaged about for her phone. Better check that Kerry was all right. She dialled the familiar number and heard it ring and ring, but the girl didn’t answer. Eventually the answer phone kicked in, sending her own voice hurtling back at her, telling her the shop was closed for now, and inviting her to leave a message. It wasn’t closed, of course. Well, she bloody well hoped not! No, either the shop was so busy that Kerry couldn’t get to the phone in time or – God forbid – something dreadful had happened. Geraldine bit down on her lower lip and wondered when she had become such a worrier.

With jumbled images flooding into her brain – of armed robbery, heart attacks, fire engines or worse – she finally saw her son walking across the terminal towards her, and felt the tears welling up quite unexpectedly from somewhere deep inside her as she rushed forward and threw herself into his open arms.

*

William Munro took off his glasses and rubbed his tired eyes. He was worried about his mother. Since his divorce had come through – a quickie, his wife had called it, not unlike their rare forays into a sex life – and Susan, with hardly a backward glance, had driven away to pastures new, he’d suddenly found he had more time on his hands, and a lot more space in his head.

Susan had been the main breadwinner and had borne the brunt of the costs, but not without a lot of spitting and hissing along the way. If this was a quickie, he hated to think what a long and protracted divorce would have been like. But it was over now. After all the bitter rows and sleepless nights, the letters bargaining and counter-bargaining, and a pile of solicitors’ bills that added up to more than the cost of his latest car, at last the house was his again. Originally quite rundown and shabby, it had been William’s long before Susan’s arrival, but it had become their marital home, added to and preened over the last few years to within an inch of its life, until it met her exacting executive requirements. And now she’d gone, and both he and the house seemed to be on the decline again.

Quite apart from the salary she brought home from the publishing house where she worked, a staggering figure which seemed to rise by leaps and bounds as she clawed her way by her long shiny fingernails towards the top of the corporate tree, she’d been sitting on a sizeable nest egg since the death of her parents and had been persuaded to use a small percentage of it to reluctantly pay off what was left of the mortgage, so at least he wasn’t weighed down by a debt he had no way of repaying. She had even been ordered, by a surprisingly understanding judge, to settle a small additional lump sum in William’s favour at the time of the divorce, which she had done grudgingly and with predictably bad grace. He hadn’t felt too sure about that. It wasn’t quite right, was it? A husband being seen as dependent on his wife, not able to provide for himself. But now the money nestled expectantly in his bank account until he made up his mind what to do with it, and finally he had the time to stop and take stock of his life. And what a mess he had made of it.

Agnes, his mother, had never particularly liked Susan. She had never actually said it aloud, but he had always known it, and had decided, probably wisely, to ignore it. Susan had been his choice and his mother had respected that, although the thin pursing of her lips and the uncharacteristic silence that surrounded her during their irregular visits had rather given the game away.

Susan had three major faults. In Agnes’s eyes, at least.

Number one. She worked, not just from nine to five, or more likely to seven or eight, but often at the weekends too. She brought paperwork home and shut herself away in the study for hours at a time, leaving William to fend for himself. William hadn’t minded too much. At least she was there with him at night, even if she often didn’t come to bed until the early hours and usually turned her back towards him as she slept.

William had been proud of his wife’s achievements, the successful authors she had discovered and nurtured, and her occasional appearances on TV book programmes and at awards ceremonies, to which he was rarely invited. He had always enjoyed having a go at various DIY projects, but more recently he had become a dab hand at shopping and dusting and cooking too. Well, if he didn’t do it, then nobody would. He didn’t like the term ‘house husband’, but perhaps, particularly in the two years or so since he had been made redundant, and with very little prospect of finding another job at his age, that was what he had gradually and unwittingly become. Looking back, that was probably when it had all started to go so horribly wrong, with a vengeance. Susan wasn’t the type of woman who wanted to be shackled to a failure, a man in an apron with no real reason even to leave the house every day. As her star rose, his had dropped like a stone, and his self-esteem along with it.

His mother was incensed on his behalf and no longer made any attempt to disguise her feelings. Yes, he was at home all day, and his spaghetti carbonara may have been so good it could win prizes, but it was the principle of the thing. Leaving the domestic side of life to the man of the house was not the way a wife should behave, and certainly not something Agnes, who had devoted her entire adult life to the needs and comfort of her own dear husband Donald until his untimely death, could ever understand.

Fault number two. Susan had never wanted children. An only child herself, and determined to stick to her belief that there were other more rewarding, and less messy and demanding things to be enjoyed in life, she had made William’s promise not to cajole, trick or persuade her an absolute condition of their marriage. And, short of signing in his own blood, William, who had met and married her a little late in life and had already resigned himself to the probability of a childless future, had felt there was no option but to agree, thus depriving Agnes of the grandchildren she could now only dream of.

And then there was number three. Susan didn’t like cats. This, in his mother’s eyes, was beyond all reason, and utterly unforgivable. Whenever they had visited Agnes in her old cottage, poor Smudge had been banished to the garden or the bedroom, his pathetic cries and the claw marks he scratched into the panelling of the old oak door frames failing to touch even the tiniest part of Susan’s cold, unfeeling soul.

Now that Susan was gone, William had found he had both the time and licence to consider his mother’s opinions, and had realised, to his dismay, that, on all three counts, she just might have been right all along. Susan wasn’t the woman he had hoped she was and, looking back, it was hard to figure out just why she had married him in the first place. He had certainly believed, at the time, that it had been for love, but Susan’s idea of love had turned out not to be quite the same as his.

With his own parents’ marriage the only model he could base his expectations on, he knew he would have liked a wife who, if not necessarily putting her husband first in all things in that old-fashioned way his mother had done, would at least have sat with him on the sofa in the evenings and rubbed his feet, or massaged his neck as they watched the news; brought him a nice mug of tea every now and then, and a couple of digestives to go with it. Perhaps, in the early years, before her career had exploded into the all-consuming passion that seemed to overshadow all else, that just might have been a possibility, but it had never happened. It was just the way she was.

In truth, she had probably accepted his proposal in the same way a drowning woman accepts a lifebelt. She was getting older, she was embarrassingly single, and he was there. He was presentable enough, and solid, and convenient. They had met during the rehearsals for an amateur production of The Sound of Music, she having just moved to the area and keen to find something to do, and someone to do it with, and him doing battle with producing lights and sounds from an ancient backstage control panel, understudying for just about all the walk-on parts, including the nuns, and wishing he’d had the nerve to try out for the part of Captain Von Trapp.

As it turned out, she had quickly realised that treading the boards was not for her and had moved on to joining, and then running, the book club at the library, and he had discovered that messing about with spotlights was far less stressful than standing beneath them. Still, some sort of spark had been lit and they had found that they enjoyed being in each other’s company and later, as things progressed, in each other’s beds. He may not have been her Mister Darcy but he just might have been her last chance. Nowadays, he thought, she probably wished she had simply carried on bobbing along without him.

He would have liked a child, of course – maybe two – to bounce on his knee, someone to inherit his house, and his money (what little of it there was), and the flecked brown of the Munro eyes, but barring that one time when her period had been late and, just for a few frantic days, he’d felt a tiny flicker of rapidly extinguished hope, that had never really been on the cards either. And, as for poor Smudge, well …

William knew he had made mistakes. He had almost forced his mother and her beloved cat into that London flat. Susan’s idea, of course. Selling the old cottage, she had insisted, before it needed some serious maintenance, before Agnes’s impending and inevitable frailty forced their hand, surely made sense. Good financial sense. But money in the bank didn’t bring happiness. After sixteen years of half-hearted marriage, and with very little to show for it, he knew that only too well.

William was fifty-seven years old. He was too chubby around the middle, and his hair was not only thinning on top but what was left of it was going decidedly grey at the sides. When he looked in the mirror he hardly recognised the face that looked back at him through his thick rimmed spectacles. Where had his life gone? How could everything had gone so horribly wrong? He wasn’t happy. He probably hadn’t been happy for years, but he’d never stopped to think about it before. And, worst of all, he was ashamed to realise that he didn’t know if his mother was happy either.

He’d call her. Yes, that’s what he would do. Or, better still, go round there. Unexpected, uninvited, like he used to in his bachelor days, turning up on her doorstep, out of the blue, with flowers and a hug, and sometimes a bag of laundry, and knowing there’d be tea in the pot – whichever of the many pots was his mother’s favourite at the time – and cake in the tin. But that, of course, had been before Susan. Susan had changed things, prised open a little gap between his mother and himself that had slowly, as the years passed, widened and deepened into an almost unbridgeable gulf.

It was time to do something about it, before it was too late. His mother wasn’t getting any younger. Neither was he, come to think of it. And, now that Susan had gone, there was nothing to stop him from being a part of her life again, and letting her be a part of his. They were both alone now. Lonely, even. Well, he knew he was. He had no idea if she felt the same. She did have old Smudge for company, of course, so there was always somebody for her to talk to, even if that somebody never talked back. Which was more than he had. William rubbed the tips of his fingers over his eyelids and yawned. He had to snap out of this self-pitying phase before he started to go all maudlin.

Only one thing for it. He’d go tomorrow, surprise her and take her out for lunch somewhere. A nice roast, with all the trimmings. She’d like that. He’d stop off on the way and buy freesias. Lots of freesias, in lovely bright colours. They were always her favourites. And cat food for Smudge. Tuna, or chicken. The expensive chunky stuff in the little foil cartons. Or maybe something tasty from the butchers, if he could find one open on a Sunday.

He hadn’t realised it before, but he’d missed that old cat. Almost as much as he’d missed his old mum. He had to admit it. Susan certainly had a lot to answer for.

*

Laura had been on shift for five hours already and her feet ached. Saturdays were notoriously busy in A & E, even in the mornings, what with the hangovers and drunken falls from the night before, and then came all the football and rugby injuries, half-dressed men trailing the mud from their boots and the drips from hastily applied bloody bandages across the newly mopped floor. And the mums who hadn’t wanted to take their sick children out of school or risk having their pay docked for taking a day off work, and preferred instead to queue up for hours at the weekend to get their five minutes with a doctor, fretting about meningitis or appendicitis, only to be told that the symptoms they were so concerned about pointed to nothing more serious than a bad cold or a touch of tummy ache. No wonder the NHS was in trouble. But at least she didn’t have to deal with those, even though she got to hear all about them from her flatmate Gina who had trained as a paediatric nurse and had been working here in Children’s A & E ever since she’d qualified. No, Laura only dealt with adult patients, not the kids or, thank God, their parents. Good job really, or she’d probably be tempted to say something she shouldn’t.

After six months in the job, she was getting used to it all now. When she’d first transferred down from the men’s surgical ward, she’d found A & E quite terrifying. Everything she’d had to do before just flew right out of the window. There was never any order. No chance to plan or prepare, so little time to stop and think. You never knew what was going to come through the door next. One minute a dad-to-be dashing in with a wife already in labour and just missing giving birth in the car on the way here, the next an old lady with a twisted ankle or some idiot with his penis stuck up a hoover tube and trying to hide it underneath his coat. From the trivial to the life-and-death to the ‘you wouldn’t believe it!’, it all just threw itself at her from the moment she arrived until she found herself exhausted, shell-shocked and waiting outside for the bus home.

The road accidents were the worst. No matter how many seatbelts and speed cameras and anti-drinking campaigns there were in the world, the accidents just kept on happening. She stood now, gazing down at the latest victim as the doctor bent over her, shining a light into her eyes, assessing the extent of the damage. The poor girl didn’t look much older than Laura herself, perhaps even younger, and she was in a bad way, the victim of a hit and run. Her clothes and hair were soaking wet, at least one leg was obviously broken, there was a nasty gash on the back of her head, and although she’d apparently been briefly conscious and trying to talk at the scene, there had been no response beyond a few incoherent mumblings since she’d been brought in, and she still hadn’t opened her eyes.

‘Can we try to get an ID? Did she have a bag with her?’

Laura turned to Bob and Sarah, the paramedics. They both looked tired, and Sarah was stretching and rubbing her back with both hands, through the folds of her fluorescent yellow jacket. Having slid her across from trolley to bed and rattled off a list of readings and what they’d already done to help her, they were getting ready to leave.

‘Sorry, no.’ Sarah shook her head. ‘She hardly spoke before she blacked out. Just muttered her name. Lily. But that’s all we have. No bag found with her at the scene. Or phone. Unless some friendly passer-by had already nicked them, of course. It wouldn’t be the first time. Couldn’t find anything in her pockets either, except a couple of keys. House, not car. There wasn’t even anything on the key ring to give us any clues. No company logo to tell us who she works for. Not even one of those Tesco clubcard fob things. Bit of a mystery girl, I’m afraid.’

‘A pretty unlucky one, too.’ The doctor stood up and wiped a hand over his forehead, a stethoscope strung idly around his thin neck and more than a hint of stubbly shadow on his chin. ‘I don’t like it when patients can’t tell me who they are or where it hurts. We’re getting a few sounds out of her, which is good, and she is responding to pain, but I don’t like head injuries, and I especially don’t like the look of this one. Her airway’s clear now, but she is struggling a bit. Can we get an urgent head CT please, nurse? Her blood pressure is pretty low too, so let’s cross match some blood. Four units. If she’s bleeding into that brain of hers, we’ll need to replace that blood ASAP. I think we’ll need the neurosurgeons to take a look at her.’

He stood back and wiped a bead of sweat from his brow, then carried on assessing his patient’s less worrying injuries. ‘Fractured left tib and fib as well as a couple of ribs, I’d say, and some fairly deep lacerations on the arms and hands, but nothing too terrible. We can deal with those. Abdomen feels okay. No distension. No obvious sign of any internal damage, apart from the head. Shame there’s no way of knowing who she is.’

And no one there waiting for her when she wakes up, Laura thought, as she returned to the nurses’ station and busied herself sorting out the paperwork and making the right calls while her colleagues carried on monitoring and did all they could to keep the girl stable.

Her stomach rumbled ominously, reminding her that she still hadn’t found time to eat. Even in the midst of others’ suffering, life and lunch had to go on. There was a broken custard cream in her uniform pocket. Emergency supplies. She took a sneaky nibble, dropping a scattering of crumbs on the desk, and glanced at her watch. Quarter to one, and she’d been up since 6.00 a.m. The cereal and toast she’d bolted down before leaving for work were nothing but distant memories.

Laura yawned as discreetly as she could and looked across at the mystery girl, surrounded by staff on all sides, unconscious and totally unaware of what was happening to her. And, with no ID, there was no way of knowing who they should call. Not even anyone to sign the consent forms. She’d want her mum at her side if it was her lying there. And her dad, obviously. But mostly her mum. There’s nothing so scary as facing stuff alone. And nothing like a mum to make it right. God, imagine having all that going on inside your own body and not knowing a thing about it. Laura shuddered and pushed the thoughts away. It’s a job, she reminded herself. Just a job. Don’t let yourself get too involved. But, how awful if the girl should die, anonymous and alone.

Death. In the middle of a normal Saturday, with the traffic going about its business outside the window, someone coughing into a bowl behind a curtain, the radio in the nurses’ kitchen spilling out sports news and tinny pop music and the weather, a vase of droopy flowers and a clutch of Thank You cards propped up along the windowsill. Death, coming out of nowhere, when it’s least expected. That was the part of her job she most dreaded, especially when the patient was so young. She knew the next few hours would be critical. Tests, monitors, ventilators, maybe an operation to relieve the pressure on her brain, everyone waiting to see whether the girl woke up or slipped away. Life and death. Such a thin line between the two, and so frighteningly easy to cross.

Quarter of an hour now since she’d been brought in, and they’d come to wheel her away already. One of the other nurses went with her. Her expression remained grim. She looked across at Laura as they entered the lift, and shook her head. There was still no change.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_14c575f0-781a-5c8b-bff2-cf3f11308482)

Ruby

The rain has stopped, but I can’t go out to play. I’m not feeling very well. Mrs Castle has put me to bed with a hot water bottle and my favourite doll. She’s called Betsy, and I think she’s wearing her best yellow dress, but someone has closed the curtains and the room is so dark that I can’t tell for sure. Her small plastic hand feels cold against mine. The room is quiet, but I can hear some of the others talking outside. They sound so far away, almost as if they’re whispering, but I know they’re not. Nobody here ever whispers.

My head hurts and I feel really hot, but I’m shivering with cold. That doesn’t make any sense at all, but I do as I’m told and stay tucked up under the blankets, only reaching my arm out when I want to take a sip from the big beaker of water by my bed. My legs ache as if I’ve been running for miles, but I don’t think I have. Mrs Castle says what I have might be catching, so the others can’t come and see me. I feel very alone in here, but I know Mrs Castle doesn’t mean to be unkind. She’s trying to help me get better, and she usually knows what’s best. She’s not as nice as a real mum, but she’s the next best thing, and I do trust her. I hope I don’t spill the water in the dark and make her cross.

I must have gone to sleep for a while. One of those deep dark sleeps, with no dreams in it. I don’t know how long I was asleep, but when I wake up, something feels different. No, everything feels different.

I can’t move my legs. I try hard but nothing happens. I can tell that Betsy has gone. I can’t feel her hand any more. In the darkness, I try to find her, but I can’t move my arms either. Or my eyes. I can’t open my eyes. Why can’t I open my eyes?

I try to think, try to remember, try to recapture the colour of the yellow in my head. Betsy’s yellow, the brightest happiest yellow ever, but everything’s just black. Black and dark and empty. And I know she’s not here. Betsy.

Is it Betsy I’m searching for? No, not Betsy. Not Betsy at all. Betsy was a long time ago. It’s Lily. Lily was this morning. Where is Lily? I try to call for her, try to speak, but nothing happens. My mouth doesn’t open. My voice doesn’t come.

Where’s Lily? And where am I?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/vivien-brown/lily-alone-a-gripping-and-emotional-drama/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Vivien Brown

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 369.76 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: What sort of mother would leave her all alone… a gripping and heart-wrenching domestic drama that won’t let you go.Lily, who is almost three years old, wakes up alone at home with only her cuddly toy for company. She is afraid of the dark, can’t use the phone, and has been told never to open the door to strangers.But why is Lily alone and why isn’t there anyone who can help her? What about the lonely old woman in the flat below who wonders at the cries from the floor above? Or the grandmother who no longer sees Lily since her parents split up?All the while a young woman lies in a coma in hospital – no one knows her name or who she is, but in her silent dreams, a little girl is crying for her mummy… and for Lily, time is running out.