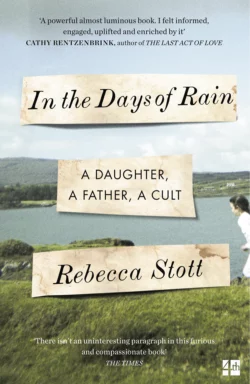

In the Days of Rain: WINNER OF THE 2017 COSTA BIOGRAPHY AWARD

Rebecca Stott

In the vein of Bad Blood and Why be Happy when you can be Normal?: an enthralling, at times shocking, and deeply personal family memoir of growing up in, and breaking away from, a fundamentalist Christian cult.‘At university when I made new friends and confidantes, I couldn’t explain how I’d become a teenage mother, or shoplifted books for years, or why I was afraid of the dark and had a compulsion to rescue people, without explaining about the Brethren or the God they made for us, and the Rapture they told us was coming. But then I couldn’t really begin to talk about the Brethren without explaining about my father…’As Rebecca Stott’s father lay dying he begged her to help him write the memoir he had been struggling with for years. He wanted to tell the story of their family, who, for generations had all been members of a fundamentalist Christian sect. Yet, each time he reached a certain point, he became tangled in a thicket of painful memories and could not go on.The sect were a closed community who believed the world is ruled by Satan: non-sect books were banned, women were made to wear headscarves and those who disobeyed the rules were punished.Rebecca was born into the sect, yet, as an intelligent, inquiring child she was always asking dangerous questions. She would discover that her father, an influential preacher, had been asking them too, and that the fault-line between faith and doubt had almost engulfed him.In The Iron Room Rebecca gathers the broken threads of her father’s story, and her own, and follows him into the thicket to tell of her family’s experiences within the sect, and the decades-long aftermath of their breaking away.

(#u1c5f95bf-23b6-5c81-b1ba-12486813a8d2)

COPYRIGHT (#u1c5f95bf-23b6-5c81-b1ba-12486813a8d2)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright © Rebecca Stott 2017

Rebecca Stott asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008209193

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008209186

Version: 2018-02-05

CONTENTS

Cover (#u21096cc9-6edd-5df7-9c6d-8626295106dd)

Title Page (#u532bad2d-3834-59c8-90f5-91bed32f39f4)

Copyright (#ucd7ceafe-63ec-5123-b907-c795bf339fd8)

Frontispiece (#u71912c1e-7091-5ad5-97b8-477c86f5e2a5)

RECKONING (#u02828ce0-d801-5fa5-b79d-dce20dae1cdc)

BEFORE (#uaaa65fbf-79b3-5101-aca3-f318fb21f20f)

DURING (#uf54301b0-585a-5a63-8edd-0e99919e78e7)

AFTERMATH (#u6a11cc71-a486-5cf7-8fe2-598884e618cd)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#ue8d2009c-44c7-5f5b-ba70-b61efd51cba6)

NOTES (#u0c1e5732-0acf-5ef3-bebb-705f8be724aa)

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY (#u1d6ba612-323d-580d-96b7-de395fe5c43e)

PICTURE PERMISSIONS (#u9043967c-5236-5bb5-88ff-42ee78600e5e)

Also by Rebecca Stott (#ue8d88d3d-93e8-5699-aea0-851808993c9b)

About the Publisher (#ub01ad716-8daa-513f-926a-7338ae33843d)

FRONTISPIECE (#u1c5f95bf-23b6-5c81-b1ba-12486813a8d2)

RECKONING (#u1c5f95bf-23b6-5c81-b1ba-12486813a8d2)

1

My father did the six weeks of his dying – raging, reciting poetry, and finally pacified by morphine – in a remote eighteenth-century windmill on the East Anglian fens. It had been built to provide wind power to help drain the land, but by the time my father and stepmother bought it, the sails and cogwheels were long gone. A previous owner had stripped out the rusting machinery, added a low nave with extra rooms and painted it a dusky pink. From a distance and with the paint flaking off, it looked like a church washed up on the banks of a river. When the local farmer covered the black fields in every direction with plastic sheeting that miraged into floodwater in certain lights, the building always looked to me like a boat, or an ark, untethered from its moorings.

It was so far from civilisation that it did not figure on GPS systems: the undertakers took four hours to reach us.

Since they’d moved into it six years earlier, my father had turned the Mill into a pagan shrine, pasting its round, six-foot-thick walls with passages from Eliot’s Four Quartets and from Yeats’s last poems, owl feathers and Celtic symbols. He glued the lines of poetry onto the plaster, and when the damp made the paper curl off he’d hammer in huge nails that made the plaster crack.

They’d bought the house on a whim a year after their wedding. They both wanted to live on flat land, he said. They both liked big skies.

‘It’s on the banks of a fen river,’ he said, when he phoned to say they’d found the perfect house. ‘The Romans used it to ship building materials across the fens. During the war a farmer ploughed up a hoard of Roman silver plates covered in tritons and sea gods just a couple of fields away, and the local Baptists used to do their baptisms here. There’s a mooring platform, so we can buy a boat.’

But you’ve got no money, I muttered to myself. How exactly are you going to buy a boat?

They drove me up to see it. We climbed through nettles and peered in through cobwebbed windows. It was beautiful, but it was also eerie and unsettling. All that sky. All that black soil. American bombers crossed the land on their flightpath from the Mildenhall airbase. Falcons hung low over the riverbank or scrutinised the fields from their posts on electricity cables.

Four months later my stepmother had turned the small circle of long-neglected riverside land into the beginnings of a garden. My father beat down the nettles with sticks. He borrowed a plough from a neighbouring farmer and broke it within a few hours. The farmer patched up the worst parts of the road. My father planted beech hedges and supervised local lads in the laying out of a lawn. He ordered and planted a grove of white birches at the far end of the garden as a birthday present for my stepmother. Their white trunks were magnificent, luminous against the black soil of the fen fields, especially at dusk.

‘He’s always had a thing for silver birches,’ she told me. ‘I prefer willows.’

My father was built on a different scale to the rest of us. In 2007, the year of his dying, he was sixty-eight, six foot four, and twenty stone. His long snow-white hair and beard would have made him look like an Old Testament prophet if it wasn’t for the combat jacket he’d taken to wearing. He’d bought it from the Army and Navy Stores to audition for the part of Mark Antony in a production of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, and now wore it all the time. He thought of himself as an ageing Antony, but to me he was Sir Andrew Aguecheek, sometimes a Falstaff, occasionally a Lear. We called him Roger in our teens, and later Rodge or Dodge or The Big Man, never Dad. He wasn’t a dad, at least not in the way that most people meant it. I’d usually just refer to him as ‘my father’ – Roger seemed an absurd name for a man built on his scale.

His head was twice the size of mine. When he’d had money he’d bought his clothes from an outsize shop called High and Mighty, but now that he was poor, most of his clothes – and my stepmother’s – came from charity shops. When he split the seams of his trousers he’d staple them back together again. It was far quicker and more efficient than sewing, he insisted when I asked what he was doing with the stapler in one hand and the washing basket in the other. My stepmother flashed me a look that meant hold your tongue. When he broke his glasses, he taped the arms back on. She flashed me a look about that too.

He had a set of dentures that had replaced some of his back teeth, and sometimes he’d take them out when he was speaking fast or reciting poetry. He’d place them on the table between us. Sometimes he’d do this in restaurants or pubs. He’d belch, too – at home and in public. His belches were loud, elongated, and reverberated like a long rumble of thunder. He belched, I think, as an act of defiance against all forms of gentility and because it made us laugh. My brothers – and then my son – competed to imitate those sounds. It became a tribal thing.

Through that final winter, increasingly lame, bilious and irascible, his pancreas riddled with the still-undetected cancer, my father – the great limping bulk of him – walked the bank of the River Lark for hours every day, following the line of the river across the fens listening to Joyce’s Ulysses on his headphones for the seventh time. He and my stepmother had planted hundreds of bulbs – fritillaries and parrot tulips – on the path up to the Mill door and in rows on the riverbank. By February they were pushing up shoots.

On Valentine’s Day in a hospital in Bury St Edmunds, doctors had finally used the word ‘cancer’ at the end of several weeks of euphemisms that had begun with ‘inflammation’ and then progressed to ‘blockage’, then ‘lump’, and then finally ‘tumour’.

‘Seems they manage bad news by drip-feeding it here,’ my father said. ‘It’s exactly three centimetres by six centimetres,’ he added, indulging his obsession for numbers, tracing the edges of the shadow on the ultrasound scan printout. ‘They don’t know how long I have. But they’ve given me a counsellor. That’s not good, is it?’

He’d have to finish his memoir now, he said, when he’d been allowed to go home and when he’d stopped swearing, raving, and thumping walls and tables with his fist. He’d begun to think about what it might mean to put his affairs in order. When he told me he was going to need my help to finish that book of his, my heart sank.

He’d started writing it eight years earlier, shortly before meeting my stepmother. He’d called it ‘The Iron Room’, after the corrugated-iron Meeting Room where he and his parents and siblings had worshipped five or six times a week when he was growing up. For the first three years he’d talked about his memoir all the time. Every spare hour he took away from his paid work as a freelance copyeditor he’d be at it: ten steps back into rewriting; one step forward into new writing. He’d sent me scores of drafts, each only slightly different from the last. I came to dread the sight of his emails in my inbox.

‘I can’t see the wood for the trees any more,’ I pleaded. ‘Let me read it when it’s finished. Then I’d be a fresh pair of eyes.’

I was relieved when the emails stopped coming, when he’d been distracted by the Mill, the garden, the broken plough, and the question of where to put the silver birches.

It was when he hit the 1960s, he said, that he’d run into trouble. He hadn’t been able to get any further. I did the calculations. That was a shortfall of forty-nine years. How long would that take him – or me – to write?

‘The Nazi decade,’ he added, as if it were an explanation, and I nodded, telling myself the morphine was addling his head. Everything after 1960 had turned into a thicket, he whispered, through tears and expletives, whilst uncorking what was probably the third bottle of wine that afternoon. But he was going to finish it, he said. He had to. He wasn’t going to let Death win that sodding chess game. He thumped his huge fist down on the arm of his chair again. Not any time soon.

He gestured at the television, a forty-two-inch flatscreen, the only piece of equipment in the cool damp interior of the curved Mill walls, on which he’d paused a scene from Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. Within the black-and-white frame two men dressed in medieval clothes sat playing chess against a wild sea.

Det sjunde inseglet/The Seventh Seal © 1957 AB Svensk Filmindustri. Still photographer: Louis Huch

‘So long as the knight keeps playing the game of chess,’ my father said, ‘Death can’t take him.’

He was damn well going to watch all fifty-eight of Bergman’s films again now, he declared.

Of all the things I might have guessed my father might have wanted to do with his remaining days, watching Ingmar Bergman films wasn’t one of them. I could only remember seven films that Bergman had directed. My father had made me watch them when I was sixteen, on afternoons when he persuaded me to skip school during my O-Levels: Wild Strawberries, Autumn Sonata, Cries and Whispers, The Seventh Seal, Winter Light, The Silence and Through a Glass Darkly. He’d buy red wine, huge loaves of still-warm bread and slabs of ham, and open a jar of his favourite wholegrain English mustard. We’d watch those films in his dusty, post-divorce flat, sitting on the floor amid piles of unpaid bills and documents and scatterings of poems. I’d go back to school – or to my mother’s house – slightly drunk, my head spinning.

I started a list on the day he showed me Death playing chess on the TV screen. Ingmar Bergman: 58, I wrote at the top of the page in my notebook, thinking I’d order them online. I’d forgotten that my father had more than forty of them in a cupboard in the Mill, that he’d been collecting them since he’d stolen into the back row of a cinema to see Wild Strawberries at the age of eighteen.

Fifty-eight. How many films could you watch in a day?

My younger brother, travelling across New Zealand on sabbatical from work, flew home and moved into the Mill. I stayed as often as I could, driving up from Cambridge every other day, leaving notes for my ex-husband and babysitters, managing a job and publishers from a phone and an internet connection that rarely worked. My sister flew over from France. My two other brothers came as often as their jobs and young families allowed them. The five of us gathered around, steeled ourselves. My stepmother ordered in food and more cases of wine and turned the thermostat dial to Constant.

In the crypt light of the Mill tower, through late February and March, we watched Bergman films together, interspersed with long hours of cricket – the World Cup had just started. We played Mozart, drank wine, cooked, and ate together at a table that seated fifteen, only a few feet from my father’s reclining chair, which was now permanently horizontal. It snowed. My son and I drove across fen dirt tracks in the dark to fetch foil boxes of Gressingham duck prepared for my father by the cooks at the White Pheasant pub at Fordham, but though he wanted to eat he had no appetite. He worked away at his memoir for several hours a day for the first week, propped up on pillows, but then, once the Macmillan nurse had increased his daily doses of morphine, he was too tired to write.

Then there was the day he told me, tears in his eyes, that he didn’t think he could finish his memoir after all. He’d gone back into the thicket, but he couldn’t face it: the muddle, the cruelty, the madness of it all. And even if he could describe those years, he whispered, as if someone might be listening in, he’d never be able to close the great gap in time, get from 1960 to now, to this.

‘Shandy’s dilemma,’ I said, and he smiled darkly. For decades he’d been persuading me to read his favourite books. Many had become my household gods now too. A webwork of in-jokes and literary references had grown up between us. We’d both read Lawrence Sterne’s mad fictional eighteenth-century memoir The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. But now that he had only weeks to live, the similarities between Tristram Shandy and my father’s own unfinished fictional memoir struck me as both tragic and ridiculous.

Poor Tristram finds he’s written several hundred pages before he’s even been born. Convinced that the oddities of his personality were caused by the fact that his father was interrupted while having sex with his mother on the night of his conception by his mother asking if he had forgotten to wind the clock, Tristram then has to explain about the clock, and to do that he has to explain about Uncle Toby, his father’s brother … and while he is trying to explain all of this, and as the pages are mounting up, there’s a knock at the door and Death is there on the threshold – cloak, scythe and all. Tristram leaps from the window and gallops to Dover to take a boat to Calais. Death takes up pursuit.

I took the bus from my house into town to buy a portable tape recorder.

‘If I ask you questions,’ I said to him as he disappeared into another cricket match, ‘it might be easier. You wouldn’t get so tired. Then I could transcribe it later. We could do short bursts, when you felt like it.’

I had bought a black tape recorder. Out in the Mill dust coated everything in hours, and I had to keep wiping the machine down. The dust bothered me. I’d never noticed it before. Dust and, even in March, fruit flies. The house was full of them. My father had started to keep a tally of the number he’d find in his wine glass. The fruit fly count joined all the other reckonings in his notebooks: daily calorie counts, his gambling winnings and losings, the daily diabetes count, the cricket scores. My stepmother just put an old beermat over her glass. She didn’t much like wine.

But although the tape recorder had been easy enough to choose in the department store that day, I hadn’t anticipated that the tapes would stupefy me. How many did I need? They came in packs of four or eight or twelve. Each of them could hold eight hours of recording. How long did he have? How far would he get? I stood in front of the display case in the shop for twenty minutes trying to do multiplication sums in my head. I picked up three packets of twelve: thirty-six tapes. That was 288 hours; 17,280 minutes.

I now have two tapes in my study drawer, next to the old tape recorder. One is full, the other only partly full. I gave the unused ones away. My father got from 1960 to 1966, two years after my birth. He ran out of time. Like Tristram Shandy, like the knight in The Seventh Seal, he didn’t get to finish his story once Death had got into the house.

What he had to tell me was far worse than I could have imagined. No wonder he’d got stuck.

When we began, I pictured my father and me in that thicket together, with scythes, torches and protective clothing, and then, triumphant, finally scaling the castle walls. We’d do whatever was needed – cut through the thorns, slay the dragon, rescue the princess – together. But we didn’t make it.

Day by day he grew quieter. His reclining chair remained in its horizontal position and his morphine-induced sleeps lasted longer. I slipped the tape recorder and the pack of tapes into the back of the cupboard where he kept his dusty film collection and his store of Spanish reds.

In the fourth week of his six weeks of dying, my father, laid out at the centre of the Mill tower, opened his eyes and summoned my brother and me, his executors. He had already given me instructions about what to do about his memorial stone, the funeral, and his extensive debts. He was struggling hard to surface from his drug-inspired dreams, to keep his eyes open, to sit up. We moved in closer.

‘This is very important,’ he stressed, raising an arm from the bed and jabbing his finger into the air with all the strength he had, his white beard and hair wild, his jaundice-yellowed eyes bloodshot.

‘You can’t leave any of those bastards alone with me when I’m asleep. You understand? You know what they’re like. They’ll take advantage. They’re like vultures.’

He knew all too well from his fifteen years as a ministering brother in the Exclusive Brethren that the distant family members who were now visiting every day as the end grew nearer would want to pray over him, help him find his way back to the Lord. He was having none of that.

Dutifully, we warned the cousins who came carrying Bibles and hymnbooks. How do you tell a Christian not to pray? What else were they supposed to do? Leave the dying man to the tortures of hellfire?

We asked them to respect his wishes. They were offended and baffled. They’d driven a long way. Many had got lost when their GPS systems had begun to tell them to turn around and make for the nearest road. They drank tea and examined the strange pagan grotto of the Mill and its many false idols. I watched a distant cousin run her eyes down the lines from Four Quartets my father had pasted above the door, her brow furrowed.

He was right to warn us to be vigilant. Despite our requests, there were two or three times when we dropped our guard. On one occasion we saw the lips of one of the visiting cousins, a kind elderly woman, pressed up against my father’s ear, while he lay commanding the room even in sleep, laid out like a fallen tree or an oversized, dusty and yellowing tomb effigy. She was whispering to him.

‘Excuse me,’ my brother said, glancing anxiously at me, embarrassed. ‘Please don’t do that.’

The promise we’d made had probably already been broken.

We never left him alone with visitors again. His eyes flickered open once to tell me as I leant across him that I was so beautiful. He woke another time to implore me to keep the scale of his gambling debts secret from my stepmother. On the night before the equinox I left the house for the first time in weeks. I’d been invited to interview for a job I’d applied for months before at the University of East Anglia. The nurse had taken me aside.

‘I’m sure he’d want you to go,’ she said. ‘He’d want you to have a good shot at it.’

From a building on the Norfolk campus, surrounded by lush green hummocks overrun with rabbits, I rang my brother every two hours. I stood in the empty toilet trying to apply make-up to my swollen face minutes before the interview, talking to my father in the mirror.

‘You’ve never been arrogant enough,’ I heard him say to me as he’d so often done. ‘Be arrogant. Nail it.’

When I got back late that night, my brother told me my father was still alive, although the nurse had said he probably wouldn’t last to the morning. I volunteered to take the night watch. No one argued; they were all exhausted. My father’s breaths rattled, paused, rattled, gasped, and began again.

‘Get him to let go,’ my brother whispered, after my stepmother had left the room. ‘He’ll listen to you.’ He helped me drag the sofa across the room so that I could sleep next to my father’s reclining chair, and then my brother was gone, the lights in the house out.

The wind rattled the windows. It was snowing again. I steadied my breathing in the darkness to match my father’s breaths; I held my breath when his stopped. I told him about the interview. I told him I’d been arrogant, that I’d done a good job. Then I told him he could let go. Immediately I wished I hadn’t said it.

My mobile rang. It was an old friend who I’d not heard from in years. He was walking home from a pub through the snow along a riverbank in the southern fens, he told me. He’d called to find out if I was all right. Startled by the sound of my sobs and my father’s laboured breathing, he stayed on the phone, talking softly about anything that came into his head until the first birds began to sing, when I finally fell asleep.

When the vice-chancellor rang early the next morning to offer me the job, I asked if I could have a few days to get back to him. My father was about to die, I said. About to die struck me as an odd phrase. I wanted to tell him how strange it was to watch death fighting to take possession of a body, of how my father’s body and the blackening ridges of his fingernails made me think of the colour and texture of a felled oak I’d once seen out on the fens, but instead I said thank you. I told him that I was, of course, delighted. I would get back to him. I just needed to attend to this particular day. Take your time, he said. Take as much time as you need.

My brother and I played Chopin in the late afternoon. At around five, the light began to fade. My stepmother and sister-in-law set out to drive the six miles across the fens to buy milk. The phone rang. I walked from my father’s chair through the nave of the Mill to the sitting room at the far end of the building to take the call. It was an old friend of my father’s asking how he was.

Across the fields in the half-light I could just make out something moving in the distance, a flash of white against the darkening trees. It was a barn owl, flying low through the dusk, following the path of the river, heading straight for the Mill, heading straight for us. I walked back down the long corridor to where my father lay breathing in rasps, my brother reading the newspaper beside him.

‘It’s coming,’ I said.

I have no idea what I thought the ‘It’ was. My brother put his newspaper down, I opened the window and we each picked up one of my father’s great gnarled hands, just as the owl passed by the front door, just as my father took his last breath, just as my stepmother opened the door with the milk, just as a great congregation of crows, lapwings and blackbirds took up their positions in rows along the electricity cables and pylons. The owl circled the house for twenty minutes and then disappeared.

Twilight on the equinox, with an owl, by a river. It was just as my father would have conjured it.

2

No one would have guessed that I’d been raised in a Christian fundamentalist cult, or that my father and grandfather were ministering brothers in one of the most reclusive and savage Protestant sects in British history. So it would always be my fault if the subject came up. It might be because I’d dropped my guard, got bored, or told a story from my childhood. Of course, once it did come up, it would always be difficult to make it go away again. People were interested; they asked questions. I’d never learned how to steer around the subject.

You can’t tell just bits of it, I’d remind myself. Once you get started the whole thing starts unravelling, like a stitch in a scarf, or a story that has no beginning, middle or end. Best not to start at all. Best to keep quiet.

No matter how many times I’d try to tell it, in pieces or at length, I’d always end up baffled, feeling as though there was a part I’d left out or forgotten, a lost moral or a punchline.

‘I was raised in a cult,’ I’d say, and then I’d recoil, embarrassed by the melodrama of the words I’d used. Were the Brethren a cult? I didn’t know. What was the difference between a sect and a cult? Was there a point on a spectrum where a sect became a cult?

‘We wore headscarves,’ I’d say. ‘We weren’t allowed to cut our hair. We weren’t allowed television, newspapers, radios, cinemas, holidays, pets, wristwatches.’

The list of prohibitions always seemed endless. I’d watch people’s eyes open wider. They’d look at me askance, then compete to ask questions, and I’d think, Oh no, not this again.

‘We weren’t allowed to talk to the other children at school,’ I’d say. ‘They told us that everyone outside the Brethren was part of Satan’s army and they were all out to get us. They called them “worldly”, or “worldlies”. If you didn’t do exactly what they said, they’d expel you. Then your family wouldn’t be allowed to speak to you ever again. People committed suicide. People went mad. Yes, this was Brighton. Yes, this was Brighton in the sixties. Yes, during flower power. In the suburbs. During the sexual revolution. Yes. It’s hard to explain.’

‘You were raised Plymouth Brethren?’ people would say. They would have heard about the Plymouth Brethren. Some might even have read Father and Son, Edmund Gosse’s beautiful memoir about growing up in a nineteenth-century Plymouth Brethren assembly. And I’d hear myself reply with a hint of superiority, ‘We weren’t Plymouth Brethren. We were Exclusive Brethren.’

‘My people were the hardliners,’ I’d say. ‘Gosse was in the Open Brethren. That was nothing. They were virtually Baptist. They had pulpits and priests and adult baptisms. They were allowed to talk to worldly people, even eat with them.’

My people? Had I really just said ‘my people’?

But even if the subject didn’t come up, my Brethren childhood would rear up like Banquo’s ghost at the dinner table, refusing to be buried. At university, when I made new friends and confidantes, I couldn’t explain how I’d become a teenage mother, or shoplifted books for years, or why I was reckless, impatient, afraid of the dark, and had a compulsion to rescue people, without explaining the Brethren, the God they made for us, and the Rapture they told us was coming.

But then, I couldn’t really talk about the Brethren without explaining about my father, how he’d been a ministering brother and then become addicted to roulette when he left the sect and stopped believing in God. I’d have to explain how he’d gone to prison for embezzlement and fraud and then ended up making films for the BBC, and that on his deathbed he’d talked about a ‘Nazi decade’ and made us promise not to let anyone pray over his sleeping body.

And I could never really tell my father’s story without telling my grandfather’s – how the Scottish ships’ chandler had migrated south to supply food to the hotels of Brighton and had ended up one of the ruling members of the Brethren and running the publishing house that printed Brethren ministries.

And to explain Brethren women, I’d have to tell the story of how my great-grandmother had been sent to an asylum in Australia for forty years by her Brethren husband not just because she had epilepsy, but because she was considered too wilful. Wilfulness isn’t allowed in Brethren women, I’d say, and then I’d realise that I didn’t really know what kind of wilful she’d been.

My family, I’d tell them, have been caught up in the Brethren for a hundred years. And then I’d notice I’d just used that funny old-fashioned phrase my mother always used: caught up in.

‘But back then, of course,’ she’d say when she was remembering something about rationing or the air raids, ‘we were caught up in the Brethren.’

My family hadn’t belonged to the Brethren, we’d been caught up in them. Caught up like a coat catching on thorns. Caught up in a scandal. Caught up in the arms of the Lord. Whichever way you phrased it, it meant you didn’t get to choose, and that there was no getting away.

And then I’d be five years old again, sitting in Meeting, listening to my grandfather preaching about the Rapture. The Lord Jesus was going to take us with him up into the air in the middle of the night, he’d say. We’d be caught up in his arms. My grandfather’s usually harsh Scottish preaching voice would go soft when he talked about the Rapture. And I’d be sitting there swinging my legs on the chair in the Meeting Room, wondering how the Lord Jesus was going to lift all of us up at the same time – there were some large and sweaty people in our fellowship. The Lord Jesus would have to be a giant to be strong enough to lift my father off the ground. I’d never seen anyone do that.

After we left the cult my father sometimes tried to explain about the Brethren to people who’d never heard of them. Though he was a man who’d seize any opportunity to hold the floor, his eyes always seemed to glaze over when anyone asked him about it, as if he was bored or reading from a script. He complained that when he tried to write an Exclusive-Brethren-in-a-nutshell section in his memoir it just came out as a lump of gawky exposition. My mother refused to talk about it at all. Best to draw a line under all of that, she’d say. No use going back in there. It won’t do any good.

3

After the funeral and the wake and the speeches and the fire we burned his chair in, my brother and I ventured into my father’s study, stacked high with papers. It all had to be cleared out, my stepmother said, if the Mill was to be sold. We rescued anything that looked important from piles of unpaid bills, receipts, photographs, and instructions for long-dead appliances.

If I was going to finish his book, I told my brother, I was going to need everything that looked as if it had anything to do with the Brethren. So we shoved stacks of letters and diaries and yellowed documents into boxes without sorting through them. My brother and my son helped me carry the six boxes up three flights of stairs in my Cambridge house and slip them into the dark and dusty space under my Victorian iron bed. I’d deal with them later, I told myself. When I was ready, when I had time.

A month after my father’s funeral, my stepmother rang to say that she’d been to see the doctors about her stomach cramps. After a series of tests they had diagnosed her with bowel cancer. She’d be fine, she said. She had her cousins nearby. There’d be a course of chemo. Her cousins would drive her back and forth from the Mill to the chemo sessions. Friends would come in to help with the garden. She didn’t need me to come out there. She didn’t need anything from any of us for now. She’d let us know if she did.

How could two newlyweds, living out an Indian summer, planting a garden on the banks of a river, both have been incubating cancerous growths, his pancreatic, hers bowel? Did his cancer explain the biliousness of his behaviour, his rants and storms, the way he’d started to talk to her in those last years, his complaints about how she refused to sit and watch Shakespeare with him?

‘Perhaps she just doesn’t like Shakespeare,’ I’d said to him. ‘It’s not a crime.’

‘Midsomer Murders,’ he said. ‘Midsomer bloody Murders. That’s the level of philistinism we are talking about here.’

‘I’d watch Midsomer Murders,’ I thought to myself, ‘if the alternative was listening to you lecture me about Wilson Knight and the late plays of Shakespeare for the fourteenth time.’

I wanted to help my stepmother. We all did. But though I drove up every few weeks, I now dreaded the sight of the Mill. Puddleglum, the little second-hand cabin boat my father and I had bought together, moored on the river under the willow tree, was now covered in mildew and leaves. The lawn grass was running to seed, the birch trees wilting in the sun. The pyre where we’d burned my father’s chair had left a scorch mark and stumps of charcoaled wood on the grass. Someone needed to rake it all in and put some grass seed down.

My stepmother was struggling not just with the chemo but also with the bank. My father had left her almost penniless. I printed out the bank statement from my father’s computer a week after the funeral. He’d placed scores of online bets in those final days, most made in the middle of the night when we’d all been asleep. Just one big win, he would have been telling himself. Just one big win so that he could leave my stepmother some money with which to pay off the debts.

I reckoned up the bets. He’d spent thousands of pounds in those last weeks by moving money from one credit card to another. It wasn’t even his money; it was the last of my stepmother’s small inheritance.

I volunteered to spend an afternoon at the Mill when my stepmother was in the hospital and her cousins were away for their summer holidays. I’d mow the lawn and water the birches, I told her. It was the least I could do.

I drove slowly up the long lane that gave way to the dirt track that followed the course of the river, coal-black fen fields in one direction and rising corn in the other. I parked the car and let myself in using the key she kept under a rock near the back door. I found the mower in the shed, the blades encrusted with dried grass.

When the mower started up, the sound seemed a rude imposition on the birdsong and silence, but the smell and the stripes of mowed grass made me feel I was pushing the encroaching wilderness back a little, that I could make all of this tidy again, at least for now.

Somewhere in the heat of the day, amid the smell of cut grass and the roar of the machine, I strayed into a corner of a flower-bed. On the edge of my vision a black cloud rose up and hummed low and close, smoke-dark against the white of the birch trunks. The first sharp sting of venom broke my concentration. The second made me release the handle of the mower. It wasn’t until I’d run screaming through the empty garden, casting off my clothes, and taken refuge in the sitting room, shaking, hurt and enraged, that I examined my skin in the mirror. I counted twenty-one stings, raised, hot mounds on my arms, neck, hands. I’d run over a wasps’ nest in the dark fen soil of that garden, in the twilight of its grieving afternoon.

Can a dead man conjure wasps? Can an owl flying at dusk take a dying man’s soul? Out there in that pagan fen landscape that disgorged Roman silver plates on the ploughshare, anything seemed possible. Like the house in Alan Garner’s The Owl Service, there were unaccountable scratchings in the eaves of the Mill now, presences everywhere.

‘Leave me alone,’ I said to the empty air. ‘Leave me a-lone. I’ll finish your book when I’m ready. You can’t make me.’

The contents of those six boxes under the bed made me think of chaos, the spillage of my father’s body after his death, the gritty cremation ashes we’d scattered on the river by the Mill, the mess of his life, the impossibility of telling the Brethren story, and my own grief. They stayed down there – under the bed, gaffer-taped up.

There was so much else to do. A new job and a commute, teenagers to cook for, homework to supervise, deadlines to meet, students to teach, lectures to write and a mortgage to pay. It was two years before the letters from debt collectors and credit card companies and court summonses stopped coming, and before I stopped posting out the photocopies of my father’s death certificate with the covering letter that explained that he’d died without assets, that his debts and bills could not be paid. By then the Mill had been sold and my stepmother had gone to Australia to live near her family.

What had I actually promised him, I began to wonder. If I was going to finish his book, I’d have to describe what happened in the sixties, in that decade he couldn’t bear to look at. No one could understand the recklessness of his behaviour without understanding that. But I didn’t want to revisit that decade any more than he had. No one in the family wanted to go back there. Sometimes my father’s cousins would refer to the years we were ‘caught up in the Brethren’, or ‘living in the Jims’, or ‘living under The System’. Most of them seemed ashamed that they hadn’t seen through it at the time; some clearly felt angry and duped. Most wanted to tell me that they should have got out earlier. But no one knew, they’d say. No one knew how bad it was going to get. Then they’d change the subject. Best not to dwell on the past. Better to focus on the future.

Even if I did get a book written, the Brethren were rich and powerful. They attacked people who criticised them. They employed legal teams. When I’d once written about growing up in the Brethren for a Sunday magazine, a Brethren ministering brother had sent me a letter to say they were praying for me; that meant they knew where I lived. I’d moved house since then, but I knew they could track me down if they wanted to, wherever I was. What would my family have to say if I started asking questions about that history now? And I’d have to find a way of not writing about my mother, of steering around her, because she wouldn’t want me to make her remember any of that.

If I was going to finish my father’s story, I’d have to write about the girl I’d been in the Brethren too, because we’d both lived in that thicket, and we’d both got caught up in its cruel aftermath. I’d have to think about the days I spent listening out for the sound of Satan’s hooves on the paving stones of Brighton, for instance, or making deals with the Lord, or hoarding tins of corned beef and condensed milk in preparation for the Tribulation. I didn’t want to think about that Brethren girl in her red cardigan with brass buttons, wearing her headscarf and clutching her Bible. I’d drawn a line between me and her. My mother was right. Perhaps it was all best left well alone.

4

Four years after my father died I won a place at a month-long silent writers’ retreat in a fifteenth-century castle just south of Edinburgh. I was supposed to be writing a novel set in nineteenth-century London, but after a week sitting at a desk staring down over the castle grounds I was deleting everything I wrote, and that wasn’t much. Every paragraph felt hollowed out; every sentence threw me off.

When I walked the castle grounds at dusk, down through the bracken and the fallen and rotting trees to the peat-red river, up to the edge of the mown lawns and the flowerbeds and back round again, I heard my father reciting parts of Revelation or Ezekiel, or Yeats’s ‘The Wild Swans at Coole’, or talking about that thicket of his. His voice echoed through the east and west wings of the castle, through the woods, in the wind. These were just aural grief hallucinations, I told myself, just flickers in my neural pathways. They were nothing out of the ordinary, nothing to worry about.

In the final week of the retreat I joined the other four writers at dusk to swim in the river that curled wide and red-brown over rocks and pebbles through the castle woods. After we’d climbed from the freezing water and pulled our towels and robes around us, we followed the path up the steep riverbank into the darkening wood. I fixed my eyes on the poet’s feet ahead of me, now level with my head, as they pressed into the leaves and bracken. When his foot slipped and he stumbled slightly, I saw, or thought I saw, a plume of smoke rising slowly from a hole in the ground that he’d disturbed.

I felt the scratchings and rustlings in my hair. The first stings began. The poet behind me, dressed in a red robe, had also been engulfed. We ran through the wood back to the castle, tripping over undergrowth in the darkness, shaking our hair and pulling off our clothes, until we were sure we’d outrun them.

We’d had a lucky escape, we told ourselves over dinner. Was it, someone asked, lemon juice or ice you were supposed to put on wasp stings? Someone passed me a tumbler of whisky. I took myself to bed early. The whisky must have addled my head, I thought, because I seemed to be hearing voices that weren’t there.

At three in the morning I woke, my pulse drumming wildly in my ears, fireworks exploding behind my eyelids. When I stumbled to a mirror to prise open a single eye, my face and neck were so swollen, taut and shiny that I stumbled backwards in shock. I was struggling to breathe.

Two days later it was all over: the early-morning drive through the dark to the emergency surgery in the director’s car, the steroids, the dosage of antihistamines large enough to floor an elephant, the semi-coma I slipped into for twenty-four hours. The doctor had counted up the hard lumps on my scalp and neck. Twenty-five stings. Enough to kill someone with an allergy, almost enough to kill someone who’d been stung before in an empty garden when a smoky swarm had risen like a ghost from a hole in the ground.

Not enough to kill, I thought, but enough to make a point.

A few years earlier, I’d discovered that the man dressed in a turquoise and pink Hawaiian shirt sitting opposite me at a Cambridge dinner party was a world expert on shamanism. I’d plagued him with questions, and if I’d failed to observe the to-and-fro turn-taking of dinner-party etiquette, I was not the only one. None of us wanted to talk about anything else.

For fifteen summers he’d lived with a shamanic tribe on the Russian steppes, he told us. He’d studied shamans as they talked their dead down.

‘Talking down,’ I said. ‘What does that mean?’ Death for me had been all about going up there, the transcendent sucking up into the air, into the arms of Jesus. I thought again of the impossibility of that body-weight of my father’s going up there, going up anywhere. Even in the blood-red plastic cremation jar his ashes had been a ton weight.

The shaman expert told us that the bereaved Sora used the shaman as an intermediary to persuade the dead person to go down into the next world.

‘Like laying a ghost?’ I asked.

‘Something like that,’ he said. ‘Though it works both ways for them. The dead and the living both have to convince the other to let them go. It takes a long time.’

Until the relatives had talked down the dead person, he told us, their spirit would be hanging around the village doing bad things, provoking, making people sick, causing the crops to fail. They had to be talked down and into the ground.

In that moment I saw my huge father up on a cliff ledge somewhere, slightly drunk, swaying close to the edge, holding forth, and my siblings and me talking him down. Or trying to. Hadn’t we done that? I asked myself. Isn’t that what we’d done out there at the Mill with the Bergman and the cricket?

But I hadn’t even started. My father was still roaming. Still talking. There were swarms of wasps, acts of provocation. It would get worse. Someone was going to have to talk him down.

5

Six years after my father died, my daughter Kezia, nineteen and home from university for the summer, went looking for an electric fan that I told her had been dismantled and would be in a cupboard somewhere. It was impossible to think, she’d complained the day before, up in my study with the summer sun beating at the closed shutters.

She texted me at the desk where I was working a mile away in the cool of the British Library.

‘I found Grandpa’s boxes,’ she wrote. ‘Can I open them?’

It took me a while to reply.

‘It’s a mess in there,’ I texted back. ‘But maybe you could sort the papers into some kind of order, if you’ve got time.’

When I came back to the house several hours later Kez was sitting in the top-floor study, shutters closed, among neat piles of papers. Knife-thin shafts of light, pouring in through the gaps in the shutters, lit up the dust. Orlando, my elderly marmalade-striped cat, tiptoed over and between the piles of papers, trying to get himself into the path of her intense attention. The fan parts lay discarded, unassembled, on the floor.

She’d gone to the pound shop round the corner and bought Post-it notes and plastic filing sleeves and filing boxes.

‘I started in 1953,’ she said, flushed. ‘There’s letters from South Africa and Grandpa’s prison diary in that file. There’s this letter he wrote to Granny when he tells her he wants a divorce and he says he wants to discuss which of you stays with her and which one goes with him. There’s all these lists of Brethren rules and pamphlets. Mad stuff. Weird. I didn’t know half of this. You’ve never told me.’

‘You can’t just tell it in bits,’ I said, though I knew I could have tried. Why hadn’t I told my children about the Brethren? Because I didn’t know how to begin to answer the questions I knew they’d ask, questions that I’d avoided for years. How do cults work? How had our family got caught up in such an extreme Protestant sect in the first place? Why would anyone have wanted to join the Brethren? How did the men get such power over the women? Why didn’t anyone rebel?

And then the girl in the red cardigan and headscarf is in the room with me again. The girl I’d once been. She’s furious. She’s sitting in Meeting listening to the men preach, and she’s trying to figure out what ‘heavenly citizenship’ is, or what it means for a house to be ‘hallowed’, or whether the Holy Spirit is male or female and how transparent it is. And she wants to know why the women aren’t allowed to speak. But she knows she can’t ask questions about that because she’s a girl and she’s not allowed to speak either. And she’s wondering why none of the women are standing up and shouting and stamping their feet like she wants to do, telling the men to stop talking all that nonsense.

My father might have died before he’d been able to face his questions, but I still had time. This was going to be my story as well as his. I might be afraid of those bullying men and their lawyers, but I’d face them down. Let them come and find me.

Kez agreed to be my research assistant for a few weeks that summer. She’d make an archive in a series of box files, label everything. While I began to piece a history together, Kez found a website.

‘They’ve renamed themselves the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church,’ she said, passing me her laptop.

‘You must have found the wrong Brethren,’ I told her. ‘Exclusive Brethren never go anywhere near the internet. Mobile phones and computers are all banned. Bruce Hales – that’s their current leader – once described the internet as “pipelines of filth”. They’d never have their own website.’

But Kez was right. This was the same Exclusive Brethren that three generations of my family and I had all been born into: same leaders, same values, same rules. There were, according to Wikipedia, 46,000 of them, living in fellowship across nineteen different countries, 16,000 in the UK. The leader, Bruce Hales, was the nephew of the man who’d been in charge when I was growing up. They’d turned it into a family dynasty and rebranded – expensively. They must have renamed themselves to throw off the bad publicity they’d been attracting for decades, I told Kez. But why would they have spent that much money? They’d never cared about public opinion before.

The website had photographs and videos of Brethren Rapid Response Teams – young people dressed in high-visibility jackets – setting up travelling kitchens to feed people who’d lost their homes in bushfires in Australia or in flooding in the UK, handing out brownies to baffled fire crews or bottles of water to commuters at King’s Cross station during a heatwave. There were photographs of choirs of Brethren girls in long skirts and headscarves singing hymns to old people in care homes. It made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up.

Family is at the heart of everything we believe and everything we do, one caption read, printed over a close-up photograph of a small girl running her hand through ears of corn. I felt a sudden flare of fury. How dare they? I thought of the suicides; the thousands of families that the Brethren had tortured and broken up over the decades; the scores of ex-Brethren I knew who would never see their parents or their siblings again. Did the members of the PR company have any idea about the group they’d agreed to promote?

But when Kez and I looked at news archives, we found that the Brethren were still getting bad press. In 2009 an Australian investigative journalist had published a best-selling book about Brethren tax-avoidance schemes. He’d exposed their aggressive political lobbying in Australia; he’d interviewed hundreds of ex-Brethren about suicides, excommunications, severed families, and post-traumatic stress.1 (#u0c1e5732-0acf-5ef3-bebb-705f8be724aa) The then Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd had described them as ‘an extremist cult that breaks up families and is bad for Australia’.2 (#u0c1e5732-0acf-5ef3-bebb-705f8be724aa)

British investigative journalists had been on their backs too. Newspaper articles about Brethren faith schools and tax-avoidance schemes had dented their reputation. In 2012 Britain’s charity watchdog had denied charitable status to the Brethren for one of their trusts in Devon. They risked losing millions of pounds in tax breaks as a result. So they’d appealed against the decision, and started up that PR and lobbying campaign to get their charitable status reinstated. But, British journalists wrote, these were no little guys being picked on by the Charity Commission. These people preached hate.

‘We have to get a hatred, an utter hatred of the world,’ Hales had told a large Brethren audience in 2006. ‘Unless you’ve come to a hatred of the world you’re likely to be sucked in by it, and seduced by it.’3

British Brethren lobbyists had been more than usually aggressive in their campaign to get their charitable status reinstated. Two Times journalists had got hold of minutes from a meeting in which Hales had urged Brethren lobbyists to apply ‘extreme pressure’ to William Shawcross, the head of the Charity Commission; ‘Go for the jugular,’ he told them, ‘go for the underbelly.’ It made me shiver.

‘That’s in hand,’ one lobbyist had replied.4

For Hales and his followers, Shawcross was a non-Brethren ‘worldy’, an agent of Satan’s system and thus fair game.

When I read that the Charity Commission had renewed the Brethren’s charitable status in 2014 I began to wonder what they’d done to Shawcross’s jugular. Then I began to wonder what they might do to mine. I could see Kez was thinking the same thing.

‘Shit,’ she said. ‘This is scary.’

Over the next few weeks Kez labelled the box files ‘Before’, ‘During’ and ‘After’.

‘You can change it later,’ she said. ‘It’s just a way of dividing up the time for now.’

I nodded. The girl in the red cardigan was in the room again.

‘You might prefer “Aftermath”,’ Kez said, ‘rather than “After”. It gives more of a sense of consequence … You know – that what happens to you and your father after is a result of the screws gradually tightening in the “Before” and “During” parts.’

‘Of course,’ I said. I was remembering the feel of the headscarf knot pressing at the back of my neck and the weight of my uncut hair hanging down my back in braided ropes. ‘Yes. That’s good.’

I made a note to watch Wild Strawberries with Kez. She’s never seen any Bergman.

A month after we started, I dreamt Kez and I were lowering ourselves down into a dark network of caves on a long rope. She was ahead of me. She had the torch. She made me think of those old stories where an innocent girl has to slay a dragon to break a curse.

Her young handwriting layered over my father’s when she put his letters in order. ‘This one’s interesting,’ she’d write on a label on the plastic sleeve. ‘He was preaching out in the black townships during apartheid.’ On the letter that my father had written to my mother about divorce, Kez wrote: ‘This one might be hard to read.’

‘Break bread?’ Kez says. ‘What’s that?’ She’s secular. I’ve raised her that way.

‘Transubstantiation,’ I tell her. ‘Jesus died on the cross and left instructions that people were to remember his death, his sacrifice, by eating bread and drinking wine. The bread was supposed to be his body and the wine his blood. We called it breaking bread.’

‘I’ll look it up,’ she said.

I’m already back there, kneading the tiny piece of warm bread in my fingers in the early hours of the morning. It’s winter. It’s the first Meeting of the day and it’s still dark outside. I’m in my headscarf and my Best Dress and I’m holding my Bible in one hand and my doll in the other.

‘We called it breaking bread,’ I’d told Kez. Who, I wondered, was this we I kept slipping back into?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/rebecca-stott/in-the-days-of-rain-winner-of-the-2017-costa-biography-award/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Rebecca Stott

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 683.69 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In the vein of Bad Blood and Why be Happy when you can be Normal?: an enthralling, at times shocking, and deeply personal family memoir of growing up in, and breaking away from, a fundamentalist Christian cult.‘At university when I made new friends and confidantes, I couldn’t explain how I’d become a teenage mother, or shoplifted books for years, or why I was afraid of the dark and had a compulsion to rescue people, without explaining about the Brethren or the God they made for us, and the Rapture they told us was coming. But then I couldn’t really begin to talk about the Brethren without explaining about my father…’As Rebecca Stott’s father lay dying he begged her to help him write the memoir he had been struggling with for years. He wanted to tell the story of their family, who, for generations had all been members of a fundamentalist Christian sect. Yet, each time he reached a certain point, he became tangled in a thicket of painful memories and could not go on.The sect were a closed community who believed the world is ruled by Satan: non-sect books were banned, women were made to wear headscarves and those who disobeyed the rules were punished.Rebecca was born into the sect, yet, as an intelligent, inquiring child she was always asking dangerous questions. She would discover that her father, an influential preacher, had been asking them too, and that the fault-line between faith and doubt had almost engulfed him.In The Iron Room Rebecca gathers the broken threads of her father’s story, and her own, and follows him into the thicket to tell of her family’s experiences within the sect, and the decades-long aftermath of their breaking away.