Great Expeditions: 50 Journeys that changed our world

Levison Wood

Foreword by Levison Wood, bestselling author of Walking the NileA comprehensive, fascinating and inspiring gallery of the great adventures that changed our world.Throughout history there have been brave men and women who dared to go where few had gone before. They broke new ground by drawing on incredible reserves of courage, fortitude and intelligence in the face of terrible adversity. Their endeavours changed the world and inspired generations.Spanning several centuries and united by the common theme of the resilience of the human spirit, this is the ultimate collection of the stories of the intrepid explorers who forged new frontiers across land, sea, skies and space.50 incredible journeys including;• Tenzing and Hillary’s conquest of Everest• Neil Armstrong’s giant leap• Christopher Columbus’ new world• Amelia Earhart flying the Atlantic• gold fever in the Yukon• the hunt for a man-eating leopard in IndiaGreat Expeditions includes not only some of the most famous journeys in history but also introduces many more that ought to be more widely recognised and celebrated.

Copyright (#ulink_50f6529a-1494-53b5-84b8-6fd738a8ae83)

Published by Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Westerhill Road

Bishopbriggs

Glasgow G64 2QT

First published 2016

© HarperCollins Publishers 2016

Text © Mark Steward 2016

Photographs © see credits (#u6e2df91c-7acd-53b7-8da5-619df564b688)

Collins® is a registered trademark of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollins does not warrant that any website mentioned in this title will be provided uninterrupted, that any website will be error free, that defects will be corrected, or that the website or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or bugs. For full terms and conditions please refer to the site terms provided on the website.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Source ISBN: 9780008196295

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2016 ISBN: 9780008222611

Version: 2016-10-22

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

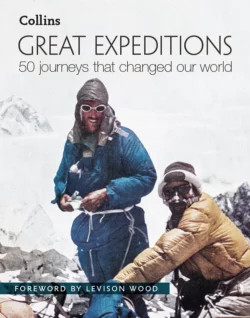

FRONT COVER: Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay preparing for another stage during their ascent to the summit of Everest in 1953. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)

INSIDE FRONT AND BACK COVER: A rare world map from 1824 by John Cary. It shows the tracks of eminent explorers of the period.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Contents

Cover (#ua0a42af2-b65b-50c2-abeb-58a98cd21a7c)

Title Page (#ua52ce063-66bd-5e28-a020-2f6e09c4fc7f)

Copyright (#ulink_8fd59554-0d29-542e-829e-78d28da567e2)

Foreword by Levison Wood (#ulink_7aedb50d-35a4-53be-bb08-b9d2397ef36c)

The Giant Leap (#ulink_7e0a2511-0939-5e79-a5a6-de914893da7a)

Apollo 11 and the Moon landings (#ulink_7e0a2511-0939-5e79-a5a6-de914893da7a)

Race to the South Pole (#ulink_ee0655ee-b1ca-506e-b6fd-5c152f7cce46)

The expeditions of Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott (#ulink_ee0655ee-b1ca-506e-b6fd-5c152f7cce46)

Darwin and the Beagle (#ulink_d225636e-48b0-52c0-89eb-1e72aa1ba65b)

Charles Darwin’s voyage on HMS Beagle (#ulink_d225636e-48b0-52c0-89eb-1e72aa1ba65b)

Star Man (#ulink_e6a81cad-c2b4-5643-8cfb-d71f7031bd47)

Yuri Gagarin: The man who fell to Earth (#ulink_e6a81cad-c2b4-5643-8cfb-d71f7031bd47)

Finding New Land

Leif Eriksson’s voyage to Vinland

Adrift in the Pacific

Thor Heyerdahl: The Kon-Tiki man

Dr Livingstone I Presume?

David Livingstone’s last journey

The Land Down Under

Captain James Cook and HMS Endeavour

Top of the World

Hillary and Tenzing: Living in the death zone

A New World

Christopher Columbus’ 1492 voyage to the Americas

Galactic Explorer

The Voyager Interstellar Mission

The American Frontier

Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery expedition

Not a Single Man Lost

Ernest Shackleton’s escape from Antarctica

The Real Indiana Jones

Percy Fawcett: In search of the lost city of gold

Gold Fever in the Yukon

The Klondike Gold Rush

The Silent World

Jacques Cousteau and Calypso

Hunting the Man-Eater

Jim Corbett and the hunt for the man-eating leopard of Rudraprayag

Flying Solo

Amelia Earhart: The Trans-Atlantic heroine

Inside the Deadly City

René-August Caillié: The outsider who made it inside Timbuktu

Save the Whale

Anti-whaling campaign, Greenpeace and the Rainbow Warrior

Heartbreak in the Outback

Burke and Wills in Australia

Travels in the Orient

Marco Polo’s journey to the fabled Xanadu

On Her Own in Darkest Africa

Mary Kingsley: Travels in the heart of Africa

Descent to the Centre of the Earth

Norbert Casteret: Into the abyss at Pierre Saint-Martin

A Lone Voice in the Wilderness

John Muir: A thousand miles to save the wild places

Fair Trade

Zheng He’s treasure voyages

With a Camel and a Compass

Gertrude Bell and her journey to Ha’il

Take Without Asking

Francisco Pizarro: The raider who ended an empire

Journey to Lhasa

Alexandra David-Néel’s trek across the Himalayas

Face of Death

The first successful ascent of the north face of the Eiger

The Solar Flight

The quest to fly around the globe without fuel

One Way Ticket

Ferdinand Magellan’s circumnavigation of the world

Scientific Exploration in the Americas

Alexander von Humboldt, the father of geography

Running the Rapids

John Wesley Powell’s exploration down the Colorado river

Farthest North

Fridtjof Nansen’s crushing expedition in the Arctic

Hidden in Plain Sight

The first woman to circumnavigate the world

Homeward Bound

Molly, Daisy and Gracie’s 1,600 km walk following a rabbit-proof fence in Western Australia

Finding Petra

Johann Burckhardt’s discovery of the fabled city

Trail of Tears

The forced migration of the Native American Tribes

Around the World on a Bike

Annie Londonderry’s ‘cycle’ around the world

Unlocking the Islamic World

The travels of Ibn Battuta

Walk the Amazon

Ed Stafford: Amazon odyssey

Natural Born Explorer

Naomi Uemura and his solo winter ascent of Denali

Marathon Man

Amputee, Terry Fox’s incredible run across Canada

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

Challenger Deep: Descent to the lowest point on Earth

The Trials of the Wager

George Anson’s voyage of pride and greed

Company Man

Abel Tasman: First white man to set foot on Australian soil

The Northwest Passage

Sir John Franklin’s search for a sea route to the Orient

Into the Empty Quarter

Wilfred Thesiger’s travels in Arabia

Across Siberia

Cornelius Rost’s escape from a Siberian Gulag

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgements and photo credits (#u6e2df91c-7acd-53b7-8da5-619df564b688)

About the Publisher

Khumbu valley, Nepal. Mount Everest is behind the Khumbu Glacier on the left side of the picture.

Foreword (#ulink_50d4bc25-ca35-5814-94cf-638c7483c7a1)

With the advance of modern technology our world seems smaller. We have apps that can translate a phrase at the touch of a button, travel is more affordable and new places can be discovered by swiping a screen. Yet there is still so much to be discovered. What has not changed since early explorers set out with little more than a map is the spirit required to undertake an expedition; the love of a challenge and the mental and physical toughness a person needs to call on when things may not be going their way. Exploration is about more than putting a flag in a map. It’s about the experiences that change us and the people we meet along the way.

I have found over the years that the best way to travel and explore is on foot. There’s nothing like treading the paths and tracks to get a real impression of a country, its landscape and its culture. The many explorers who went before me didn’t have helicopters on hand or gadgetry to make their lives easier. Whether they were trekking the banks of the Nile or scaling peaks in the Himalayas; breaking new trails in the jungles of Asia or crossing unknown deserts, it was these early pioneers who inspired me.

David Livingstone’s journey to find the source of the Nile was a large part of the motivation behind my own nine-month expedition walking the length of the world’s longest river. It was reading about these adventures as a young man that set me on my path, starting in the army and eventually undertaking world-first expeditions of my own. Like Livingstone, I was also documenting my journey, keeping scribbles in a notebook rather similar to the one he used. But then again, I was able to use technology such as cameras he could only have dreamt of. We were both creating our own records of a shared experience more than 150 years apart.

As I have learned, modern day expeditions are not immune to danger. Whilst the promise of a helicopter can give the impression of a safety net, there is still a huge risk for anyone undertaking a remote climb or trek. Nature, whether it’s driving winds, freezing temperatures or intense heat, poses just as much risk today as it did a hundred years ago. The results can be tragic, as anyone who followed Walking the Nile will know. For early explorers such as Amundsen, Shackleton and Nansen, the Poles proved the ultimate challenge. Things inevitably go wrong but it’s at these times that a person can show what they’re made of. This book is a celebration of the few brave people who defied terrible odds and conditions to prove something vital to both the world and themselves. For every risk, the rewards are huge.

The stories featured in this book form an extensive list of human achievement that has had a huge impact on the world today. No space mission has quite captured the imagination of the world like the Apollo 11 moon-landing or had such a profound impact on science as Charles Darwin’s voyages. Sometimes these stories, such as the Challenger journey to the deepest point on Earth, are so extraordinary they can seem like science fiction. Personally, the expeditions that I love are the long-distance overland journeys, such as those by the intrepid Frenchwoman Alexandra David-Néel who in 1924 crossed the Himalayas in midwinter and entered a forbidden Tibet in native disguise. Perhaps less well known, but an achievement that deserves to be recognised.

There is still much to explore and plenty of experiences to be had, and I am sure that within our lifetime we will see more Great Expeditions that are just as impressive as the ones detailed in this book. I for one hope to keep following in the footsteps of the explorers who have gone before.

LEVISON WOOD

The Giant Leap (#ulink_6f019f30-bf96-549e-8943-aae77dac3b38)

Apollo 11 and the Moon landings (#ulink_6f019f30-bf96-549e-8943-aae77dac3b38)

“The ‘a’ was intended. I thought I said it. I can’t hear it when I listen on the radio reception here on Earth, so I’ll be happy if you just put it in parenthesis.

Neil Armstrong commenting on his own quote and the most famous space line ever spoken: ‘That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind’.

WHEN

July 1969

ENDEAVOUR

Putting a man on the Moon

HARDSHIPS & DANGERS

The crew risked death by accident, fire, solar radiation and even drowning on their return to Earth.

LEGACY

The crew achieved perhaps the single greatest ‘first’ in human history. The Apollo program transformed the fields of astronomy, aerospace and computing, and put space at the forefront of our collective imagination.

Official photo of Apollo 11 crew (left to right): Neil Armstrong, Commander; Michael Collins, Command Module Pilot; and Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin Jr., Lunar Module Pilot.

The first step on the moon by a man was also the last of an eight-year odyssey by the largest expedition team in human history. On 20 July 1969, Neil Armstrong had travelled 384,000 km (240,000 miles) in four days – the equivalent of nine circumnavigations of the Earth – through the deadly vacuum of space. But the Apollo program that put him there had employed the skills of 400,000 people for nearly a decade. More than 20,000 companies and universities had supplied equipment and brainpower. The project cost $24 billion and was easily the largest and most technologically creative endeavour ever made in peacetime. It was nothing less than the longest, most dangerous and most audaciously conceived expedition the world had ever seen. The catalyst was the singular vision of one man.

Race into space

On 12 April 1961, the Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space. Just eight days later, US President John F. Kennedy (who had only been in office for three months) wrote this in a memo to his Space Council:

‘Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space, or by a trip around the moon, or by a rocket to go to the moon and back with a man. Is there any other space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win?... Are we working 24 hours a day on existing programs? If not, why not?’

His choice of words – ‘beating’ and ‘win’ – made it very clear that he was intent on winning the Space Race.

Apollo takes to the skies

At this point, the United States was lagging behind the Soviet Union. One American astronaut, Alan Shepard, had flown into space, but he had not achieved orbit. The first Russian Sputnik craft had orbited the Earth in 1957.

NASA was given the funds to launch a completely new space program – Apollo – dedicated to achieving Kennedy’s stated goal ‘before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth’. A new Manned Spacecraft Center (nicknamed ‘Space City’) for human space-flight training, research, and flight control was built in Houston, Texas. A vast launch complex (now known as The Kennedy Space Center) was built near Cape Canaveral in Florida.

Hundreds of the planet’s greatest scientific brains would spend the coming years solving seemingly impossible problems at breakneck speed, to create a rocket and spacecraft that could get a crew into orbit, then onwards to the Moon, down to its surface, and then repeat all these steps in reverse.

The program suffered a serious early setback. The Command Module of Apollo 1 caught fire on 27 January 1967, during a prelaunch test, killing astronauts Virgil Grissom, Edward White, and Roger Chaffee. But NASA learned from the disaster and went back to the drawing board to make their craft safer. In December 1968, the second manned Apollo mission, Apollo 8, was successfully launched. It became the first manned spacecraft to leave Earth orbit, reach the Moon, orbit it and return safely to Earth. After two more successful launches, Apollo 11 was cleared for launch on 16 July 1969.

A Saturn V rocket blasts the Apollo 11 mission towards the Moon on July 16, 1969. Astronauts Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin Aldrin are in the cone-shaped Command Module in the middle of the picture.

Sitting in their tin can

On 16 July, 1969, Neil Armstrong, Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin and Michael Collins strapped themselves into Columbia, the command module of Apollo 11. This tiny conical cabin would carry the three astronauts from launch to lunar orbit and back to an ocean splashdown eight days later. Connected to the bottom of the command module was the cylindrical service module, which would provide propulsion, electrical power and storage during the mission. Below that was Eagle, the lunar module that would make the actual descent to the Moon’s surface.

Their tiny habitat was bolted on to the top of a colossal Saturn V rocket. At 111 m (363 ft) high, Saturn V stood 18 m (58 ft) taller than the Statue of Liberty. It is still the tallest, heaviest, and most powerful rocket ever built.

The Saturn V rocket being prepared and taken to the launch pad in 1969.

‘But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic?

.........

We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills; because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win…’

President John F. Kennedy

The journey between worlds

The gargantuan engines roared for eleven minutes, burning 2 million kg (5 million lb) of liquid oxygen and kerosene at over 13 metric tonnes per second to hoist the three astronauts into the heavens.

Two and a half hours after topping 40,000 km/h (25,000 mph) and reaching orbit, another rocket burn set them on course for the Moon. The astronauts spent the next three days coasting through the void. On the fourth day they passed out of sight behind the Moon and fired rockets to ease them into orbit 100 km (62 miles) above the dusty surface.

Armstrong and Aldrin climbed into the Eagle and said farewell to Collins. He would remain alone in Columbia in orbit while his colleagues walked on the surface. The landing craft separated and for twelve minutes a computer guided Armstrong and Aldrin down. Fear flashed through mission control five minutes into the descent when Aldrin instructed the computer to calculate their altitude and it blinked back an error message. Should they abort? Engineers coolly worked out that it was safe to override the message and go on.

But just a few minutes later there was further cause for alarm. Armstrong saw that the crater the computer was piloting the Eagle into was strewn with large boulders. He took manual control and guided the craft further downrange, burning extra fuel. When the Eagle finally touched down in the Sea of Tranquility, it had a mere 30 seconds of fuel left.

The Lunar Module ascends from the Moon with Earth just above the horizon.

Men on the Moon

Touchdown was the softest landing that the pilots had ever experienced. Lunar gravity is one-sixth of that on Earth, and the astronauts felt no bump on landing — they only knew they were definitely down when a contact light came on.

‘Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed!’ said Armstrong, unquenchable joy surging in his normally cool voice. But rather than step outside straight away, Armstrong and Aldrin spent the next four hours resting in the cockpit. They yearned intensely to get outside but were also full of trepidation. Would their spacesuits protect them from the vacuum? Would they be able to take off again?

The Eagle landed in the Bay of Tranquilitity, top right on this spectacular image of our Moon.

The time had come. Neil Armstrong stepped out of the Eagle, descended the ladder and walked on the moon, 109 hours and 42 minutes after he had left planet Earth. An estimated 530 million people watched Armstrong’s televised image and heard his voice describe the event as he took ‘...one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind’. After 20 minutes, Aldrin followed him and became the second human being to make footsteps in moondust.

An astronaut’s boot print in moondust.

The astronauts put the TV camera on a tripod about 9 m (30 ft) from the lander to transmit their actions. Half an hour into their moonwalk, they spoke to President Nixon by telephone. The two astronauts spent the next two and a half hours collecting rock samples, taking photographs and setting up experiments. As well as planting a US flag, they also left a Soviet medal in honour of Yuri Gagarin, who had been killed in a plane crash the year before.

Armstrong and Aldrin were on the Moon’s surface for 21 hours and 36 minutes. This included seven hours of sleep. The ascent stage engine fired successfully and they lifted off, leaving the descent module behind. Just under four hours later, Eagle docked with Columbia in lunar orbit, and the three crew were reunited. Columbia headed home. Three days later, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins fell back to Earth as heroes.

The Times reports the start of the astronauts’ return journey.

New York City welcomes the Apollo 11 crew home with a ticker tape parade down Broadway and Park Avenue.

Next stop, the stars

This astonishing achievement inspired a whole generation with the technical and creative possibilities of space. The Apollo program brought 382 kg (842 lb) of lunar rocks and soil back to Earth, transforming our understanding of the Moon’s geology and history. The program funded the construction of the Johnson Space Center and Kennedy Space Center. Huge advances in avionics, telecommunications, and computers were made as part of the overall Apollo program.

The Apollo 11 Command Module on display at Cape Canaveral.

Politically, the Space Race was won – decisively – by America. JFK had been assassinated six years before his dream became reality but the Soviets had been beaten, as he had wanted.

Apollo 11 was the first in a flurry of launches. Apollo 12 became the second successful mission to the Moon just four months later, in November 1969. Apollo 13 famously had a malfunction on the journey out and had to return home without touching down on the Moon. Apollos 14 to 16 all landed safely on the lunar surface. In December 1972, Apollo 17 was the sixth – and final – manned spacecraft to make a Moon landing. In total, twelve Apollo astronauts walked on the Moon. No humans have gone further than Earth orbit in the decades since.

One of the most unexpected glories of the expedition was actually an image of home: the extraordinarily delicate beauty of the blue Earth as seen from our natural satellite. It was a sight that few had imagined but which utterly transfixed all astronauts who witnessed it.

President Barack Obama welcomes Apollo 11 astronauts Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin (left side) and Neil Armstrong’s widow, Carol (seated third from the right), to the Oval Office on 22 July 2014. Also seated are NASA Administrator Charles Bolden and Patricia Falcone, Director for National Security and International Affairs.

Race to the South Pole (#ulink_8f3c2ee6-c2e9-5a5d-b4cd-581e5c19faa2)

The expeditions of Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott (#ulink_8f3c2ee6-c2e9-5a5d-b4cd-581e5c19faa2)

“I may say that this is the greatest factor – the way in which the expedition is equipped – the way in which every difficulty is foreseen, and precautions taken for meeting or avoiding it. Victory awaits him who has everything in order — luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.

From The South Pole, by Roald Amundsen

WHEN

1910–12

ENDEAVOUR

Becoming the first human to reach the South Pole.

HARDSHIPS & DANGERS

Extreme cold, frostbite, hunger, exhaustion.

LEGACY

Roald Amundsen was the first man to reach both poles. He also made the first voyage through the Northwest Passage. Robert Scott reached the South Pole after Amundsen and died on the return journey. But his stoicism in the face of certain death continues to earn respect.

Until colour photography was invented, only whalers and explorers were able to fully appreciate the beauty of Antarctica.

The search party had found the tent. Steeling themselves, the men looked inside. As they expected, the emaciated bodies of Captain Robert Scott and two companions lay frozen solid, shrouded in drifting snow. Scott’s sleeping bag was thrown open and his coat was unfastened; he had hastened the end. Somewhere outside, forever lost in the merciless Antarctic, were two other men who had also perished. Such was the price they paid for coming second in the race to the South Pole.

Natural born heroes

When Robert Falcon Scott left Britain on his 1911 attempt to be first to reach the South Pole, he was already a national hero. He had commanded the Discovery Expedition of 1901–04, which included another great explorer, Ernest Shackleton. Scott and Shackleton had walked further south than anyone else in history: they got to within 850 km (530 miles) of the pole.

While Scott was making his record-breaking South Pole approach, Roald Amundsen was making a pioneering polar trip at the opposite end of the world. Born in 1872 into a Norwegian family of maritime merchants, Amundsen had been forced by his mother to study medicine. When she died he packed up his books and, aged 21, left university for a life of adventure. Amundsen led the 1903–06 expedition that was the first to traverse the Northwest Passage. On this trip he also learned some Inuit skills that would stand him in good stead; how to use sled dogs to transport stores and how much better animal skins were at insulating in the cold and wet than the heavy, woollen parkas typically used by European explorers.

An extract of a German map from the period showing the explorers’ routes to the South Pole.

Unfinished business

In 1909, Scott heard that his former fellow explorer Shackleton had got to within 180 km (112 miles) of the Pole on his Nimrod Expedition before being forced to turn back. Scott was aware that other polar ventures were being planned and, gripped by ‘Polemania’, he duly announced that he would lead another Antarctic expedition. Hopes were now high that a Briton would be the first to stand on the bottom of the world, and Scott did not want to disappoint. His expedition sailed from Cardiff in June 1910 on the former whaling ship, Terra Nova on a seven-month journey to Antarctica.

While Scott was looking south, Amundsen had his sights set on the North Pole. However, in 1909, he heard that two separate American expeditions, led by Robert Peary and Frederick Cook, had both attained this goal, so he decided instead to head for Antarctica. (Peary and Cook are both now generally considered not to have attained the North Pole.) Amundsen and his crew left Oslo on the Fram (the ship previously used by Fridtjof Nansen, see page 188), heading south on 3 June 1910.

When Scott got to Melbourne, Australia, he found a telegram from Amundsen, announcing that he was ‘proceeding south’. The Terra Nova stopped for supplies in New Zealand and then turned south in late November. Scott now had a run of what he termed ‘sheer bad luck’. A heavy storm killed two ponies and a dog, and also caused 10,200 kg (10 tons) of coal and 300 l (65 gallons) of petrol to be lost overboard. The Terra Nova then got stuck in the pack ice for twenty days before managing to break clear.

The Fram’s run south in the meantime, had been relatively smooth.

A recent satellite image from a similar vantage point. The Ross Ice Shelf, Transantarctic Mountains (top half) and Ross Sea (lower half) are clearly visible.

A historical Bird’seye view map of Amundsen’s South Pole Expedition. Scott’s route can also be seen (with added annotations) as it followed the same route as Shackleton’s 1907–09 expedition.

The rivals meet at the end of the Earth

The Pole attempts had to be made in the Antarctic summer as conditions were too severe during the rest of the year. This period of relatively better weather and constant light only lasted from November to March. The plan was to arrive during one summer, set up camp and see out the winter, then push for the Pole when the next summer’s weather window opened.

The Terra Nova finally reached Ross Island on 4 January 1911. Scott’s team set up their base camp at a cape near where he had camped on his Discovery Expedition nine years before. They had at least nine months before they would make their Pole attempt. In the meantime, Scott was determined to keep busy, and to pursue their scientific goals. He sent a party east to explore King Edward VII Land and Victoria Land. This team was returning westward when it was astonished to see Amundsen’s expedition camped in the Bay of Whales, an inlet on the eastern edge of the Ross Ice Shelf. The Norwegians had arrived on 14 January. Amundsen was friendly to the Englishmen, offering them a welcome to camp nearby and care for their dogs. These offers were declined and the party returned to base camp. Scott wrote about the meeting in his journal: ‘One thing only fixes itself in my mind. The proper, as well as the wiser, course is for us to proceed exactly as though this had not happened. To go forward and do our best for the honour of our country without fear or panic.’

Roald Amundsen in furs, c.1912.

Different men, different strategies

There were three main stages to be tackled on the 1,450 km (900 mile) trek to the Pole: crossing the Ross Ice Shelf (an area the size of France); ascending a glacier to reach the polar plateau; and then crossing that plateau to the Pole itself. Once at the pole the journey then had to be done in reverse.

The two expeditions planned different strategies for their attempts. Amundsen would use his beloved dogs to pull his team and supplies all the way to the Pole. Scott would use a combination of ponies (which Shackleton had used on his record push), dogs and motor sleds to haul the big loads across the ice shelf. This would allow the men to save their strength for the ascent onto the plateau and the push for the Pole, which they would do pulling their own sleds.

They could not haul all the supplies they would need, so both parties had to lay out caches of food on their routes. This had to be done before winter arrived to allow the expeditions to start in earnest in the following spring.

On 27 January, Scott hurriedly began laying supplies but their ponies were not up to the task and several died. The men were also slowed by a vicious blizzard. These delays made Scott decide to lay their main supply point, One Ton Depot, 56 km (35 miles) north of its planned location. This decision would cost the returning party dearly.

The Norwegian party used skis and dog sleds to lay supply caches at 80°, 81° and 82° south on a route aimed directly at the Pole, without major incident.

Winter descended and both expeditions settled down in their base camps to ride it out.

Captain Scott writing in his journal in the expedition hut in October 1911, before setting out for the pole.

Across the ice shelf

On 8 September 1911, Amundsen’s team set out for the Pole but within days they were beaten back by savage weather. They immediately began preparing for another attempt and, on 19 October, a group using four sledges and fifty-two dogs set off from base camps on a direct line south. They spent nearly four weeks crossing the ice shelf before reaching the base of the Antarctic plateau. Here they discovered a new glacier, which was shorter and steeper than the colossal Beardmore Glacier that Scott was ascending. They shot several of their dogs for food. After a four-day climb up this icy staircase, they reached the plateau on 21 November.

Scott’s motor sleds, laden with supplies, departed on 24 October, but only ran for 80 km (50 miles) before breaking down. The drivers had to haul the gear themselves in an exhausting 240 km (150 mile) trek to the rendezvous. Scott’s main party left base camp on 1 November 1911 — Amundsen had already been going for twelve days. Scott’s teams reached the start of the Beardmore Glacier on 4 December. By now they were more than two weeks behind Amundsen.

They were tent-bound by a blizzard for five days and then took nine days to ascend the gargantuan 200 km (125 miles) long Beardmore Glacier. Scott’s team stepped onto the lifeless Antarctic plateau on 20 December. They caught up a little time here and the final team of five men — Scott, Wilson, Oates, Bowers and Evans – set out on foot for the Pole.

‘The worst has happened’

Scott’s team slogged on across the vast white emptiness, passing Christmas on the ice. On 30 December, their hearts lifted a little as they had caught up with Shackleton’s 1908–09 timetable. However, in reality they were all suffering from exhaustion, frostbite and hunger. They passed Shackleton’s record mark of (88° 23’ S) on 9 January. Despite their pain, they could feel that their prize was within reach. They trudged on.

Amundsen’s expedition with piles of equipment, boxes of stores, and dogs.

Scott’s disappointed party at the South Pole, 18 January 1912. Clockwise from top left: Oates, Scott, Evans, Wilson, Bowers. Frostbite is plainly visible on their faces.

On 17 January 1912, Scott looked up from the endless snow at his feet to see a black flag fluttering above a small tent. Amundsen had led his five men, sixteen-dog team on a straight run to the Pole. They encountered little difficulty on the plateau and on 14 December 1911 they made the first human footprints at the bottom of the world. They had erected a tent and left a letter detailing their achievement.

Scott had been beaten to this long-sought goal by thirty-four days. ‘All the daydreams must go,’ wrote the anguished explorer in his diary. ‘Great God! This is an awful place.’ There was nothing for the distraught men to do but start the 1,300-km (800-mile) return journey. This was a savage undertaking and the exhausted team were pained with frostbite and snow blindness. The first man to die was Edgar Evans. He succumbed on 17 February after falling down a glacier.

The remaining four trekked on but Lawrence Oates’ toes had become severely frostbitten and he knew that he was holding back his colleagues. On 16 March, Scott wrote in his diary that Oates stood up, said ‘I am just going outside and may be some time,’ then walked out of the tent and was never seen again.

‘We knew that Oates was walking to his death... it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman.’

The three surviving men camped for the last time on 19 March. A ferocious blizzard kept them in their tent in temperatures of -44°C (-47°F) and sealed their fate. They died of starvation and exposure 10 days later. They were 18 km (11 miles) short of One Ton Depot. Had it been in its planned location, they would have made it. Scott was the last to die.

‘Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more. R. Scott. Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people.’

Both quotes from Captain Scott’s diary

To the victor, the spoils

Amundsen’s team arrived back in base camp six weeks after reaching the Pole, on 25 January 1912. They were in Australia at the start of March. News of their success was telegraphed to the world.

Scott was hailed as a tragic hero, brave in the face of certain death. His legend was held up to inspire generations of Britons. When Amundsen found out about Scott’s death, he said, ‘I would gladly forgo any honour or money if thereby I could have saved Scott his terrible death.’

The search party which found Scott and his colleagues collapsed the tent over the bodies then built a cairn of snow above, placing a cross made from their skis on top. Today, after a century of snowstorms, the cairn, tent and cross now lie under 23 m (75 ft) of ice. They have become part of the ice shelf and have already moved 48 km (30 miles) from where they died. In 300 years or so the explorers will once again reach the ocean, before taking to the water and drifting away inside an iceberg.

Extracts from The Times newspaper reporting on the contrasting outcomes.

Darwin and the Beagle (#ulink_3c3ad6d2-2677-5c8f-ada9-3c9b94e692c5)

Charles Darwin’s voyage on HMS Beagle (#ulink_3c3ad6d2-2677-5c8f-ada9-3c9b94e692c5)

“When on board HMS Beagle, as naturalist, I was much struck with certain facts in the distribution of the inhabitants of South America, and in the geological relations of the present to the past inhabitants of that continent. These facts seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species...

Introduction to Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection

WHEN

1831–6

ENDEAVOUR

Charles Darwin was the naturalist on this five-year circumnavigation of the world.

HARDSHIPS & DANGERS

The two summers spent around Tierra del Fuego and Cape Horn, with violent weather and unhelpful natives.

LEGACY

Darwin amassed evidence from the many places visited on the voyage that led him to develop the theory of evolution.

Charles Darwin, photographed towards the end of his life.

Charles Darwin served as the naturalist of the five-year voyage of the surveying ship HMS Beagle, during which it circumnavigated the world. His observations of the natural world, particularly in the southern hemisphere, provided the evidence which led him to develop the theory of evolution.

The university drop-out

Darwin was born in Shrewsbury in 1809, the son of a prominent local physician and the grandson of two leading lights of the Industrial Revolution, Josiah Wedgwood and Erasmus Darwin. He was educated at Shrewsbury School, and in 1825 he went with his brother to study medicine at Edinburgh University. His dislike of anatomy and surgery quickly drove him away from a career in medicine and he left Edinburgh without a degree in 1827. The following year, he started at Christ’s College Cambridge, with the aim of becoming an Anglican clergyman. Most importantly, he became a friend of John Henslow, a botany professor who enthused Darwin with a love of and fascination in nature.

Darwin graduated in 1831 and was then recommended by Henslow as a gentleman collector for what was planned as a two-year trip to South America, commenting that his recommendation was ‘not on the supposition of yr. being a finished Naturalist, but as amply qualified for collecting, observing, & noting any thing worthy to be noted in Natural History’. After some persuasion, Darwin’s father agreed to the trip (important because he had to fund all his son’s costs, apart from food, which was provided by the Admiralty).

Into the open ocean

The trip was to be on HMS Beagle, a small survey ship that was 27 m (90 ft) long and weighed in at around 245 tonnes (241 tons). The boat was captained by Robert Fitzroy, a keen amateur naturalist and scientist, and, along with surveying the coast of South America, one of its missions was to trial the new Beaufort wind scale. Darwin shared a cabin with the ship’s mate and a midshipman, and it was also his study. And so it was on 27 December 1831, HMS Beagle sailed out of Plymouth — a day late, for the crew had celebrated Christmas Day too enthusiastically and were unfit to leave the day before. Darwin was soon badly stricken by seasickness, a bad beginning to a long voyage.

It was too rough to land on Madeira and, because there had been a cholera outbreak in England, they were refused permission to land in the Azores. On 16 January, they reached the Cape Verde islands, where Darwin’s work of observation, collecting and recording began. His questioning mind could be seen at work — why for example, was there a band of shells 14 m (45 ft) above sea level in a cliff when such a band would have been formed under the sea?

HMS Beagle, as equipped for the voyage. Darwin shared the poop cabin (top left in the cross-section) with two others and with the ship’s library of 400 books.

The first new species

The Beagle reached the coast of Brazil by the end of February 1832, and while the ship did much surveying work, Darwin spent much of the next six months on land, exploring and gathering large collections of specimens from the country around Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires and Bahia Blanca. By the end of November, Darwin had shipped back two consignments of specimens, from preserved beetles to fossils of animals previously unknown.

The Beagle then sailed south, to Tierra del Fuego, arriving there on 17 December: ‘...we were saluted in a manner becoming the inhabitants of this savage land. A group of Fuegians partly concealed by the entangled forest, were perched on a wild point overhanging the sea; and as we passed by, they sprang up and waving their tattered cloaks sent forth a loud and sonorous shout.’

Lessons from the primitives

Darwin was shocked by the primitive nature of the Fuegians (meeting one group he commented ‘these were the most abject and miserable creatures I anywhere beheld’). Puzzled by why anyone would live such a tough life in so unforgiving a place he concluded ‘Nature by making habit omnipotent, and its effects hereditary, has fitted the Fuegian to the climate and the productions of his miserable country.’

The route of the Beagle, as recorded by Captain Fitzroy in his account of the voyage, published in 1839.

The Beagle ventured to Cape Horn: ‘we saw on our weather-bow this notorious promontory in its proper form — veiled in a mist, and its dim outline surrounded by a storm of wind and water’. The weather around Cape Horn was severe and the ship was nearly overwhelmed:

‘At noon a great sea broke over us … The poor Beagle trembled at the shock, and for a few minutes would not obey her helm; but soon, like a good ship that she was, she righted and came up to the wind again. Had another sea followed the first, our fate would have been decided soon, and for ever.’

HMS Beagle in the Strait of Magellan, from an 1890 edition of Darwin’s Journals. Monte Sarmiento, ‘the most sublime spectacle in Tierra del Fuego’ according to Darwin, looms over the scene.

In April 1833, the Beagle left Tierra del Fuego for the Falkland Islands, very recently after Britain had reasserted sovereignty, replacing the Argentinians, and then returned to Montevideo. While the Beagle continued its survey work, Darwin explored inland around Buenos Aires and Montevideo, rejoining the Beagle on 28 November. They returned to Tierra del Fuego and then sailed along the Strait of Magellan: ‘The inanimate works of nature – rock, ice, snow, wind, and water – all warring with each other, yet combined against man – here reigned in absolute sovereignty.’ Finally, on 10 June 1834 they reached the Pacific, and on 23 July they arrived at the warmth of Valparaiso. From here Darwin went on a six-week expedition into the Andes.

The surveying of southern Chile continued into 1835. Here he saw the effects of a devastating earthquake on the city of Concepción; he noticed that rocks has been forced upwards by the earthquake, evidence of the force of rock movement that was slowly pushing up the Andes. In the months that followed he undertook various inland expeditions until 7 September, when the Beagle sailed from Peru for the Galapagos Islands.

The green sea turtle (left) and the marine iguana (right) were two of the animals on the Galapagos Islands that fascinated Darwin.

The insatiable collector

The Beagle stayed for five weeks and Darwin was an exhaustive collector: ‘The natural history of this archipelago is very remarkable: it seems to be a little world within itself; the greater number of its inhabitants, both vegetable and animal, being found nowhere else,’ and the evidence amassed provided the spur for Darwin to develop his theory of evolution.

The Beagle then set sail across the Pacific, reaching Tahiti in November, northern New Zealand in December, and Sydney on 12 January 1836. The Beagle next sailed to Tasmania, then onto the Keeling Islands (now Cocos Islands) in the middle of the Indian Ocean. By June they had reached Cape Town in South Africa, where they stayed for a month, and then it was on to St Helena and Ascension Island.

Finally, after a brief return to Brazil, the Beagle docked at Falmouth on 2 October 1836. Fitzroy had completed much valuable surveying work and Darwin had gained the knowledge and enthusiasm to devote his life to natural history, and his greatest achievement, the publication in 1859 of On the Origin of Species, which outlined his landmark theory of evolution.

A caricature of Darwin as an ape, on the cover of the French satirical magazine La Petite Lune, published in 1878.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/levison-wood/great-expeditions-50-journeys-that-changed-our-world/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Levison Wood

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Foreword by Levison Wood, bestselling author of Walking the NileA comprehensive, fascinating and inspiring gallery of the great adventures that changed our world.Throughout history there have been brave men and women who dared to go where few had gone before. They broke new ground by drawing on incredible reserves of courage, fortitude and intelligence in the face of terrible adversity. Their endeavours changed the world and inspired generations.Spanning several centuries and united by the common theme of the resilience of the human spirit, this is the ultimate collection of the stories of the intrepid explorers who forged new frontiers across land, sea, skies and space.50 incredible journeys including;• Tenzing and Hillary’s conquest of Everest• Neil Armstrong’s giant leap• Christopher Columbus’ new world• Amelia Earhart flying the Atlantic• gold fever in the Yukon• the hunt for a man-eating leopard in IndiaGreat Expeditions includes not only some of the most famous journeys in history but also introduces many more that ought to be more widely recognised and celebrated.