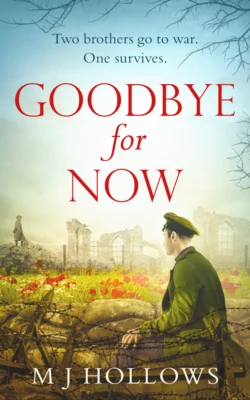

Goodbye for Now: A breathtaking historical debut

M.J. Hollows

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 736.08 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Two brothers, only one survives. As Europe is torn apart by war, two brothers fight very different battles, and both could lose everything… While George has always been the brother to rush towards the action, fast becoming a boy-soldier when war breaks out, Joe thinks differently. Refusing to fight, Joe stays behind as a conscientious objector battling against the propaganda.On the Western front, George soon discovers that war is not the great adventure he was led to believe. Surrounded by mud, blood and horror his mindset begins to shift as he questions everything he was once sure of.At home in Liverpool, Joe has his own war to win. Judged and imprisoned for his cowardice, he is determined to stand by his convictions, no matter the cost.By the end of The Great War only one brother will survive, but which?This breathtaking novel is perfect for fans of Jenny Ashcroft, Kate Furnival and Louisa Young.