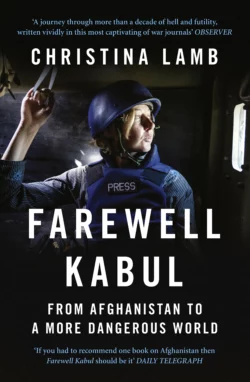

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Christina Lamb

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Политология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 386.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the award-winning co-author of ‘I Am Malala’, this book asks just how the might of NATO, with 48 countries and 140,000 troops on the ground, failed to defeat a group of religious students and farmers? How did it go so wrong?Twenty-seven years ago, Christina Lamb left Britain to become a journalist in Pakistan. She crossed the Hindu Kush into Afghanistan with mujaheddin fighting the Russians and fell unequivocally in love with this fierce country of pomegranates and war, a relationship which has dominated her adult life.Since 2001, Lamb has watched with incredulity as the West fought a war with its hands tied, committed too little too late, failed to understand local dynamics and turned a blind eye as their Taliban enemy was helped by their ally Pakistan.Farewell Kabul tells how success was turned into defeat in the longest war fought by the United States in its history and by Britain since the Hundred Years War. It has been a fiasco which has left Afghanistan still one of the poorest nations on earth, the Taliban undefeated, and nuclear armed Pakistan perhaps the most dangerous place on earth.With unparalleled access to all key decision-makers in Afghanistan, Pakistan, London and Washington, from heads of state and generals as well as soldiers on the ground, Farewell Kabul tells how this happened.In Afghanistan, Lamb has travelled far beyond Helmand – from the caves of Tora Bora in the south to the mountainous bad lands of Kunar in the east; from Herat, city of poets and minarets in the west, to the very poorest province of Samangan in the north. She went to Guantánamo, met Taliban in Quetta, visited jihadi camps in Pakistan and saw bin Laden’s house just after he was killed. Saddest of all, she met women who had been made role models by the West and had then been shot, raped or forced to flee the country.This deeply personal book not only shows the human cost of political failure but explains how short-sighted encouragement of jihadis to fight the Russians, followed by prosecution of ill-thoughtout wars, has resulted in the spread of terrorism throughout the Islamic world.