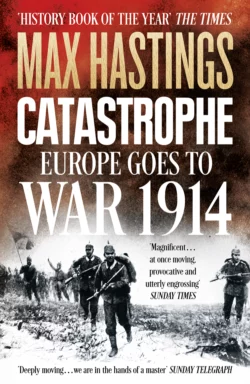

Catastrophe: Europe Goes to War 1914

Макс Хейстингс

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Новейшая история

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 854.20 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A magisterial chronicle of the calamity that crippled Europe in 1914.1914: a year of unparalleled change. The year that diplomacy failed, Imperial Europe was thrown into its first modernised warfare and white-gloved soldiers rode in their masses across pastoral landscapes into the blaze of machine–guns. What followed were the costliest days of the entire War. But how had it happened?In Catastrophe: 1914 Max Hastings, best-selling author of the acclaimed All Hell Let Loose, answers at last how World War I could ever have begun. Ranging across Europe, from Paris to St. Petersberg, from Kings to corporals, Catastrophe 1914 traces how tensions across the continent kindled into a blaze of battles; not the stalemates of later trench-warfare but battles of movement and dash where Napoleonic tactics met with weapons from a newly industrialised age. A searing analysis of the power-brokering, vanity and bluff in the diplomatic maelstrom reveals who was responsible for the birth of this catastrophic world in arms. Mingling the experiences of humbler folk with the statesmen on whom their lives depended, Hastings asks: whose actions were justified?From the out-break of war through to its terrible making, and the bloody gambles in Sarajevo and Mons, Le Cateau, Marne and Tannenberg, this is the international story of World War I in its most severe and influential period. Published to coincide with its 100th Anniversary, Catastrophe: 1914 explains how and why this war, which shattered and changed the Western world for ever, was fought.