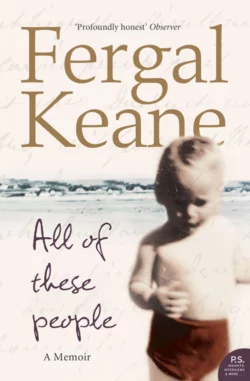

All of These People: A Memoir

Fergal Keane

In a memoir of staggering power and candour, award-winning journalist Fergal Keane addresses his experience of wars of different kinds, some very public and others acutely personal.During his years of reporting from the world's most savage and turbulent regions, Fergal Keane has witnessed the violence of the South African townships and the terror in Rwanda, the most extreme kinds of human behaviour, the horror of genocide and the bravery of peacekeepers faced with overwhelming odds. As one of the BBC's leading correspondents, he recounts extraordinary encounters on the front lines. Alongside his often brutal experiences in the field, he also describes unflinchingly the challenges and demons he has faced in his personal life growing up in Ireland.Keane’s existence as a war reporter is all that we imagine: frantic filing of reports and dodging shells, interspersed with rest in bombed-out hotels and concrete shelters. Life in such vulnerable areas of the globe is emotionally draining, but full of astonishing moments of camaraderie and human bravery. And so this is also a memoir of the human connections, at once simple and complex, that are made in extreme circumstances. These pages are filled with the memories of remarkable people. At the heart of Fergal Keane's story is a descent into and recovery from alcoholism, spanning two generations, father and son; a different kind of war, but as much part of the journey of the last twenty-five years as the bullets and bombs.

All of these people

A Memoir

Fergal Keane

For My Parents

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#ucc1f5d09-f44c-57fc-9087-a96165b0ce66)

Title Page (#u52d57876-5c6d-5999-8952-1b91f5fd9fb9)

Dedication (#udc5ca908-ffdb-5ea2-868c-f6a1fb408077)

PROLOGUE (#ucc185917-5bb8-5aa3-9d99-d6fb18289dc4)

CHAPTER ONE Echoes (#ua93d9ab7-921b-5912-961e-15842bf667e6)

CHAPTER TWO Homeland (#u9d164092-50ed-5992-8848-17e586723935)

CHAPTER THREE The Kingdom (#ua5d06d4f-7875-5ecc-a1c8-55f187fec7a0)

CHAPTER FOUR Tippler (#u41172439-4f37-5b45-b346-f54018d13f0f)

CHAPTER FIVE Shelter (#u99aff9e1-bb79-5056-9cab-65b17c6973c5)

CHAPTER SIX ‘Pres’ Boy (#ud213bcf6-2011-547b-afa6-7fab6ebb1f8f)

CHAPTER SEVEN The junior (#uff83eb10-5a70-52d4-a4c4-3c67ab718230)

CHAPTER EIGHT Local Lessons (#ud6c99d24-74d0-5275-a632-ff2f33d691f5)

CHAPTER NINE Short Takes (#u0f10d851-e68b-5fe7-983b-bed67ee2b37c)

CHAPTER TEN Into Africa (#u1002822d-292f-5a7c-94be-4d4acf71f510)

CHAPTER ELEVEN The Land That Happened Inside Us (#uc1aa1972-f9a6-5f7c-98e3-a7670d7e3ec7)

CHAPTER TWELVE Cute Hoors (#u1a0a6811-8ddf-5321-9cc5-1cddb1153647)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN North (#u4e7323a0-94b2-598e-bc43-d727042bc499)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Marching Seasons (#uc9ecc093-d1ad-52b5-99b2-b68eab341689)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Visitor (#uc4361146-3c8b-5d06-8603-d00b8ad1a95b)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN A Journey Back (#ua3b3d633-ad46-55fd-bb43-c9889c1366e7)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Beloved Country (#u7f70d60d-9619-5042-ae92-5a675b73fec3)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN People Are People (#u8c348091-b5ab-534b-ae52-e55cef6cf63c)

CHAPTER NINETEEN Limits (#u29c04553-aa48-5a7a-a446-0e6f62937674)

CHAPTER TWENTY Valentina (#u09f468ac-d7fd-5b45-982a-ebcf4c7f6486)

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE Witness (#u5f33485f-c6e7-5527-98ae-ffbee29bd6f4)

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO Consequences (#u51093505-667d-5ade-8e11-394faf642d02)

P.S. (#u56dc1b88-2f25-5756-a7dd-4395b208121a)

About the author (#u3e6b63ce-3f8a-51a0-8e15-efe053c4278e)

From Our Own Correspondent (#ucde0166b-ca13-5449-aa9e-771bcf4f49c9)

LIFE at a Glance (#u94d3c094-cbae-5640-9776-3b85006ad83a)

Top Ten Favourite Books (#u76c5bb29-5ab4-521d-b604-f5b267b467a4)

A Writer’s Life (#u87705ee1-966e-51e9-afe2-d32c19e05945)

About the book (#u7107e8f9-48c5-5ca0-a5a1-a68de5688adf)

In the Bone Shop of the Heart: Writing All of These People (#u934374df-4dcb-5e65-b38a-aabf554fd736)

Read on (#u63f46350-9101-5462-bbcb-70ad016fcc1e)

Have You Read? (#uc9ed0d55-ecc9-54b7-812c-197c32cd410c)

If You Loved This, You Might Like… (#u9d2fc6be-f494-5848-a3e7-21fe347295b1)

EPILOGUE A Last Battle (#u2ec97f89-ff3a-5514-ab87-a0f1337ed058)

INDEX (#u45c14788-1833-52ff-abca-1e53c3eeb903)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u909ad10d-30b2-5241-a599-ecf8f99a0fe5)

About the Author (#u21f29e2f-8b51-50ec-b86d-c45a94efb484)

Praise (#ud6bbd243-16da-5bc9-b5f8-6cecdaa235af)

Copyright (#u58fe7852-7f2e-5b90-8015-d1c11fca00ad)

About the Publisher (#uc72d1ef2-40b3-558b-9b40-6a31395a5a95)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_f267c6c7-6757-5176-a9ec-8eb571174cab)

Early in the new year, 2004, I was due to meet a friend for coffee in Chelsea. As I waited an elderly man entered and went to the front of the line. I felt a flash of annoyance and tried to attract the attention of the staff. ‘He’s jumping the queue,’ I said. But nobody heard me. The manager came and showed the man to a table. He turned, slowly, and I looked into the face of my father.

In the fourteen years since his death he had not changed.

My father did not recognise me but I knew him: those poetic lips, the melancholy vagueness of the old king fighting his last battle, the same shock of greying black hair, the thick-rimmed glasses, the tweed hat and scarf I gave him once for Christmas, the aquiline nose – the Keane nose! Crossing O’Connell Bridge in Dublin one day Paddy Kavanagh had turned to my father, his friend, and remarked: ‘Keane, you have a nose like the Romans but no empire to bring down with you!’

The man in the coffee shop was not, of course, really my father, but it was his face I saw. After being seated at a table near the window he had begun to talk to himself. I heard him. An English accent – upper class, not at all like my father’s. ‘I want to admire the magic,’ he said, and made a grand, kingly gesture, waving his hand. The manager laughed.

They both laughed. It was the kind of language Éamonn, my father, would have used. Expansive. I want to admire the magic…

This book began as an attempt to describe my journalistic life and the people and events which have shaped my consciousness. I had come through several traumatic personal experiences and arrived at middle age – a time when men often collide with their limitations and feel the first chill of mortality. I needed to take stock of where I had come from, examine the influences which had formed me, and to look at where I might be going. There were also certain resolutions to be made in the way I lived my life. Chiefly they concerned the risks I was taking in different conflict zones of the world.

What I did not understand then was that another imperative would emerge. This book would also become a journey in search of someone I had loved but with whose memory I was painfully unreconciled. When I tried to describe my journalistic life and world, I found my father waiting for me at every corner; the past intruded so acutely on the present that I found myself pulled constantly towards a man who had been dead for more than fourteen years. For much of my adult life I had lived in confusion about my father: thoughts of him made me feel both angry and sad. I could never understand him or the manner in which our relationship had affected my life.

When I look now at my journalism, at the preoccupations which have remained constant – human rights, the struggles for reconciliation in wounded lands, the impulse to find hope in the face of desolation – I know that I am largely defined by the experiences of childhood. Since much of that childhood was framed by the realities of growing up in a household dominated by my father’s alcoholism, it might be assumed that I found my father’s influence to be a wholly negative one. This book acknowledges the pain of the past, but writing it has revealed to me that both my parents gave me gifts that were profound and lasting. Their passionate natures and belief in justice were my formative inspiration. They were, above all, people of instinct. I doubt that either of them had a calculating bone in their bodies.

I did not always realise the good they had handed on; I too often saw the past through the prism of an angry, alienated child. But a personal crisis in the closing years of the last millennium set me on a journey towards understanding my father. I travelled part of his road of suffering and found that I was more like him than I knew.

Two physical landscapes dominate this book. One is the country in which I grew up and which, for all my exile’s tendency to criticise, I love and feel very proud of. I was a child of the Irish suburbs. The familiar worlds described in the conventional Irish narratives – misery in the tenements, a happy romp through the fields to school – were not mine. I was born of middle-class parents and grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s amid the death throes of traditional Catholic Ireland. I saw the emergence of a modern state at a time when one part of the island was descending into sectarian war and the other, my own country, was experiencing a social revolution unprecedented in its history.

The other landscape of this book is Africa, a place I loved from a distance as a child and which would draw me back again and again as an adult. Ireland and Africa are bound together for me. Events in Ireland have often helped me to make sense of what I saw in Africa, and my experiences in Africa, particularly in the age of apartheid, helped to illuminate possibilities of change in my homeland. I regard both as home in the larger sense of that word: they are places where I can feel a sense of belonging. In Africa I witnessed the death of people I knew. I saw friends taken away before their time. I saw the very worst of man and felt death brush my own shoulder. But I also met the best friend of my adult life, a man whose willingness to forgive was an inspiration.

Writing this book I have also tried to answer some fundamental questions: why was I willing to risk my life repeatedly? How did war change me? Why did I go to the zones of death? I have found that the motivations were as complex as the consequences. By the time I drove into Iraq during the war of 2004, a perilous drive from the Jordanian border to Baghdad, I had been a journalist for twenty-five years, fifteen of which had been spent reporting conflict.

I recently wrote down as many of these war zones as I could remember – Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Albania, Burundi, Congo, Cambodia, Colombia, Eritrea, Gaza, Northern Ireland, Sudan, Philippines, Rwanda, South Africa, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Lebanon…all places where circumstances had reduced the daily lives of men and women to misery. I found that as I travelled the zones of conflict there was much that seemed familiar, echoes of the history of my own country. As a boy in primary school I had listened to legends and half-truths. I had heard the stories of an Irish war handed down by former combatants in my family. I was conscious too of the stories we were not told – of civil war and atrocity, the lies of silence used by our leaders to bury the past. Those echoes became louder as I wrote this book.

I have been well rewarded for my travels. My reporting of war has won plaudits, awards, public attention. Yet I found the longer I stayed on the road the more I became aware of the psychological backwash of war. This, of course, touched the participants and victims most of all, but for the professional witnesses there was also a high price to be paid, not mitigated by the fact that we had chosen to put ourselves in the line of fire.

For me the greatest consequence of life at war, particularly after the Rwandan genocide of 1994, was a feeling of guilt. The cataclysm which engulfed the Great Lakes region of Africa in the late spring of 1994 left many of the witnesses with lasting feelings of responsibility, or in some cases a rumbling but impotent rage. Sometimes you could experience all those feelings within seconds of each other. We had watched the unimaginable – the slaughter of nearly a million people in one hundred days – and we had survived. All of my friends who covered Rwanda came away with something more than memories: we were, in different ways and with varying degrees of intensity, haunted. In my case the story followed me for a decade. It follows me still. Rwanda led me into two extraordinary relationships: one an encounter of love, the other a confrontation with a man whom I felt myself loathing and fearing, and who in the end I would have to face in a courtroom in the middle of Africa.

While writing this book I have been surprised by the number of times I laughed at the recollection of this or that event and how inspired I have felt at the memory of certain individuals. Even in the worst of situations there have been kind gestures, compassionate acts; often these kindnesses have come from those who have been most abused, people who insisted, when we met, on recognising our shared humanity.

The title of this book, All of These People, comes from a poem by the Ulster writer, Michael Longley, one of the most sensitive chroniclers of the pain caused by the Troubles. It is his tribute to those who have inspired him; I carry a little photocopy of this poem wherever I travel in the world.

All of these people,alive or dead,are civilised.

The civilised are those who can love, forgive and hope. The world is full of them. My mother was one such person. My father too.

In this account there are individuals whom I have left out, either because they would not wish to be included, or because doing so might put them in the way of harm. In describing the relationship with my father, I am conscious that it is only my version of events, my direct conversation with somebody who is long gone but whose presence remains a constant in my life. Others will see him differently and remember different things about him.

I hope that anyone reading this book will come away from it with a sense of optimism. I am an optimist. I believe there is more good in humanity than evil, and that we are capable of changing for the better. This is the continuing lesson of my personal life as much as the public sphere in which I have operated. I make my claim on the entirely unscientific basis of one man’s lived experience: it is the view from the long journey, not blind to the madness but awake to our finer possibilities.

CHAPTER ONE Echoes (#ulink_0165e791-59ee-5f85-b5a6-5d91d72ac088)

Ideal and beloved voices Of those who are dead, or of those who are lost to us like dead.

Sometimes they speak to us in our dreams; sometimes in thought the mind hears them.

And for a moment with their echo other echoes return from the first poetry of our lives – the music that extinguishes far-off night.

‘Voices’, C. P. CAVAFY

Here is a memory. It is winter, I think, some time in my seventh or eighth year. There is a fire burning in the grate. Bright orange flames are leaping up the chimney. The noise hisses, crackles. On the mantelpiece is a photograph of Roger Casement gazing at us with dark, sad eyes. My father loved Casement. An Irish protestant who gave his life for Ireland. In this memory my father sits in one chair; my mother is opposite him. They are rehearsing a play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by a man called Tom Stoppard. It will open at the Gate Theatre in Dublin in a few weeks’ time. Ihear my parents’ voices going back and forth. My father’s voice is rich, deep. It rolls around the room, fills me up with wonder. My mother’s is softer, but so intense, the way she picks up when he stops. Never before have I seen such concentration, such fidelity to a moment. I don’t really understand this play. Two men are sent to kill another man. It’s about Hamlet, my mother explains. The two men are in the Shakespeare play. But who is Hamlet? It doesn’t matter. I am enchanted. I feel like part of some secret cell. I don’t want them to stop. I want this to last forever. Us being together in this calm; the words going on, softly, endlessly. Years and years later I try to find his voice, her voice, as they were on that night, when there was calm. If I will it hard enough I can hear them. My parents, the sinew and spirit of me.

My mother is pretty. She smells of Imperial Leather. Her hair is brown – long, and she asks me to comb it. Six pence for ten minutes. Half a crown for twenty. My father is darker and in the sun his skin tans quickly. Like a Spaniard. He says the Keanes are descended from Spanish sailors who were wrecked off the west coast of Ireland during the Spanish Armada. Such pictures he paints of our imagined beginnings along the rocky coast of Galicia, the great crossing of Biscay, the galleons smashed on the black rocks of Clare, the soldiers weighed down by their armour, sucked down into the cold. ‘Only the toughest survived,’he says.

His eyes are green like mine: ‘Like the heather,’ he says. When he poses for a publicity photograph for one of his productions my father looks like a romantic poet, a man who would sacrifice everything for his art. He wore a green tweed jacket; I remember the scratch of it when he embraced me. And the smell of John Players cigarettes, the ones in the little green boxes with the sailor’s head on the front, and I remember how the smoke would curl above his head. Sometimes in the mornings I would see him stooped over the bathroom sinkin his vest, peering into a small mirror as he shaved. Afterwards he would have little strips of paper garlanded across his face to cover the tiny razor cuts. He used to tell a joke about that:

A rural parish priest goes into the barber’s and asks for a shave. The barber is fond of the drink and crippled with a hangover. His hands are shaking. Soon the priest’s face is covered in tiny little cuts.

Exasperated, he says to the barber: ‘The drink is an awful thing, Michael!’

The barber takes a second before replying.

‘You’re right about that, Father. ‘Tis awful. Sure the drink, Father…it makes the skin awful soft.’

I have a cottage by the sea on the south-east coast of Ireland. Every year I go there in August, the same month that I have been going there for over forty years. I am well aware that my addiction to this place is a form of shadow chasing. It was here, on the most restful of Irish coasts, that I enjoyed my happiest hours of childhood. What else are you doing, going back again and again, but foraging for the ghosts of lost summers?

Last August I went to a party at the house of a friend overlooking Ardmore Bay. We had sun that day and the horizon was clear for miles. In Ireland when I meet older people, they will frequently ask one of two questions: ‘Are you anything to John B. Keane?’ or ‘Are you Éamonn Keane’s son?’ Yes, a nephew. Yes, a son. My father and his brother were famous and well-loved figures in Ireland. Éamonn, the actor, and John B, the playwright. Although they are both dead, they are still revered. In Cork city people will usually ask if I am Maura Hassett’s boy: ‘Yes I am, her eldest.’ They will say they remember her, perhaps at university or acting in a play at one of the local theatres. ‘She was marvellous in that play about Rimbaud and Verlaine.’

At the party in Ardmore I was introduced to an elderly man, an artist, who had known my parents when they first met. In those days he was a set designer in the theatre. My parents were acting in the premiere of one of my uncle’s plays, Sharon’s Grave, about a tormented man hungry for land and love: ‘I have no legs to be travelling the country with. I must have my own place. I do be crying and cursing myself at night in bed because no woman will talk to me,’ he says. He is physically and emotionally crippled, a metaphor for the Ireland of the 1950s.

Stunted and isolated, Ireland sat on the western edge of Europe, blighted by poverty, still in thrall to the memory of its founding martyrs, a country of marginal farms, depressed cities and frustrated longings, with the great brooding presence of the Catholic Church lecturing and chiding its flock. My parents were children of this country, but they chafed against it remorselessly. The artist told me that he’d sketched them both during the rehearsals for the play.

‘What were they like?’ I asked him.

“The drawings? They were very ordinary,’ he replied.

I said I hadn’t meant the drawings. What had my parents been like?

‘Well, you could tell from early on they were an item,’ he said.

We chatted about his memories of them both. He praised them as actors, and talked about the excitement their romance had caused in Cork. The love affair between the two young actors became the talk of Cork city. The newspapers called it, predictably, a ‘whirlwind romance’. The news was leaked to the papers by the theatre company. Éamonn and Maura married after the briefest courtship. The love affair caught the imagination of literary Ireland. For their wedding the poet Brendan Kennelly gave them a present of a china plate decorated with images of Napoleon on his retreat from Moscow, and there were messages of congratulation from the likes of Brendan Behan and Patrick Kavanagh, both friends of my father. When the happy couple emerged smiling from Ballyphehane church, members of the theatre company lined up to cheer them, along with a guard of honour made up of girls from the school where my mother taught.

Once married they took to the road with the theatre company with Sharon’s Grave playing to enthusiastic houses across the country. In a boarding house somewhere in Ireland, a few hours after the last curtain call, I was conceived.

Several weeks after I met the artist who sketched my parents a brown parcel arrived at my home in London. Inside were two small photographs of his drawings. They looked so beautiful, my parents. My father handsome, a poet’s face; my mother, with flowing brown hair and melancholy eyes. Looking at those pictures I remembered a line I’d read somewhere about Modigliani and Akhmatova meeting in Paris: Both of them as yet untouched by their futures. The artist had caught them at a moment in their lives when they believed anything was possible. There is a poem by Raymond Carver where he remembers his own wedding. This remembrance comes after years of desolation, amid the collapse of his marriage.

And if anybody had come then with tidings of the future they would have been scourged from the gate nobody would have believed.

That was my parents in the year they met, 1960. I was the eldest of their three children, born less than twelve months after they were married and we would live together as a family for another eleven years.

I showed the sketched images of my parents to my eight-year-old son. He looked at them briefly and then wandered off to play some electronic game. I felt the urge to call him back, to demand that he sit down and contemplate the faces of his grandparents. But then, I thought, why would he want to at eight years of age? To him the past has not yet flowered into mystery. Anyway, he knows his grandmother well. Maura is a big figure in his life. He never met his grandfather whose gift for mischief he shares, and whose acting talent has already come down along the magic ladder of the genes.

He is occasionally curious though. ‘What was your dad like?’ he asks. ‘My dad and your granddad,’ I always say. Usually a few general words suffice, before his mind has hopped to something else. But I am sure the question will return when he is older. Just as I ask my mother about her parents, and wish I could have asked my father about his, my son will want to put pieces together, to find out what made me and, in turn, what shaped him.

My parents were temporary exiles from Ireland when I was born. After the successful run of Sharon’s Grave, Éamonn was offered the role of understudy to the male lead in the Royal Court production of J. M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World. They lived in a small flat in Camden Town from where my mother could visit the antenatal clinic at University College Hospital in St Pancras. In those days Ireland had no national health service and an attempt to introduce a mother and child welfare scheme had been defeated by the Catholic hierarchy. They considered it a first step on the road to communism.

In London my mother was given free orange juice and milk and tended to by a doctor from South Africa and nurses from the West Indies. Remembering this she told me: ‘It was the best care in the world. It was the kind of treatment only rich people could afford at home.’

On the day of my birth my father was out drinking and my mother went to hospital alone. It was early January and it had been snowing. A taxi driver saw her resting in the doorway of Marks & Spencer and offered her a free lift to the hospital. By now she would have known a few of the harsher truths about the disease of alcoholism. For one thing an alcoholic husband was not a man to depend on for a regular income or to be home at regular times. Éamonn appeared at the hospital later on and, as my mother remembers it, there were tears of happiness in his eyes when he lifted me from the cot and held me in his arms for the first time.

A week or so later I made my first appearance in a newspaper. It was a photograph of the newly born Patrick Fergal Keane taken as part of a publicity drive for a forthcoming film on the life of Christ. The actress Siobhan McKenna was playing the role of the Virgin Mary in the film and the producers decided that a picture of her with a babe in arms would touch the hearts of London audiences. McKenna was the foremost Irish actress of her generation and was also playing the female lead in The Playboy of the Western World. As a favour my parents had agreed to the photograph. In the picture I am held in the arms of McKenna who gazes at me with a required degree of theatrical adoration.

The declared reason for the embrace had nothing to do with film publicity. The actress had agreed to become my godmother. Strictly speaking this involved a lifelong commitment to ensuring my spiritual wellbeing. I was not to hear from Siobhan McKenna again. Holy Communion, confirmation and marriage passed by without a word.

Thirty years later I met her at a party held in Dublin to celebrate the work of the poet Patrick Kavanagh. My father had come with me. It was a glorious summer’s evening and Siobhan looked radiant and every inch the great lady of the stage. My father approached her and introduced me: “This is Fergal. Your godson.’

Siobhan smiled and threw her arms around me, and the entire gathering of poets and playwrights seemed to stop in their tracks as she declaimed: ‘Sure it was a poor godmother I was to you.’ She stroked my cheek and then stepped back, looking me up and down: ‘But you turned out a decent boy all the same.’

My father laughed. I laughed.

‘That’s actors for you,’ he said.

Éamonn and Maura both loved books. Our home in Dublin was full of them. I remember so vividly the musk of old pages pressed together, books with titles like Tristram Shandy, The Master and Margarita and 1000 Years of Irish Poetry. I have that last one still, rescued from the past. My father liked the rebel ballads:

Oh we’re off to Dublin in the Green in the Green .. ., Where the rifles crash and the bayonets flash To the echo of a Thompson gun.

My mother would sing ‘Down by the Sally Gardens’. Her voice trembled on the high notes.

Down by the Sally Gardens, My love and I did meet, She passed the Sally Gardens, With little snow-white feet. She bid me take love easy As the grass grows on the weir Ah but I was young and foolish And now am full of tears.

My parents were the first to foster in me the idea that I might someday be a writer. The first stories they read to me were Irish legends. As I got older they urged me to read more demanding works. I believe my first introduction to the literature of human rights came when my mother gave me a copy of George Orwell’s Animal Farm when I was around ten.

My father wrote plays and poems, but it was his gift for interpreting the writings of others which made him one of the most celebrated Irish actors of his generation. Sometimes when my father was lying in bed at night rehearsing his lines I would creep in beside him. After a while he would switch out the light and place the radio on the bed between us. We would listen to a late-night satirical programme called Get An Earful of This which had just started broadcasting on RTE. Get an earful of this, it’s a show you can’t miss. The show challenged the official truths of Ireland and poked fun at its political leaders. My father delighted in this subversion. In my mind’s eye I can still see him beside me laughing, his face half reflected by the light shining from the control dials of the radio, the red tip of his cigarette glowing in the dark and me falling asleep against his shoulder.

Nothing in either of my parents’ natures fitted the grey republic in which they grew up. Sometimes my father’s outspokenness could get him into serious trouble. Once he was hired to perform at the annual dinner of the Donegalmen’s Association in Dublin. The usual form was for the President of the Association to speak, followed by a well-known politician, and then for my father to recite poems and pieces of prose.

On this particular night the politician was a narrow-minded Republican, Neil Blaney, who in 1957 was Minister of Posts and Telegraphs, the department which controlled RTE, my father’s place of employment. At the time the government of Éamonn de Valera was making strenuous efforts to bring RTE into line after some unexpected outburst of independence on the part of programme-makers. My father later claimed that Blaney had denounced the drama department at RTE in the course of his speech to the Donegalmen. The historian Professor Dermot Keogh went to the trouble of researching the old files on the incident. He published the official memorandum a dry account of what was surely an incendiary occasion:

Before the dinner started Mr Keane left his own place at the table and sat immediately opposite where the Minister would be seated. When the Minister arrived, and grace had been said, Keane began to hurl offensive epithets across the table at the Minister and had to be removed forcibly from the Hall. Mr Keane was suspended from duty on 22nd November.

Quoting a civil service inter-departmental memorandum, Professor Keogh wrote:

Described as ‘a substantive Clerical Officer’ who had been ‘seconded to actor work as the result of a competition held in 1953’, Keane submitted ‘an abject apology in writing for his behaviour.’ He said he had been feeling unwell before the dinner and had strong drink forced on him to settle his nerves, with the result that he lost control of himself and did not realise what he had been saying.

The memorandum added tartly:

The action did not appear to Mr Blaney to be that of a man not knowing what he was doing. Mr Blaney said that Keane came very deliberately to the place where he knew the minister would be and that when Keane arrived in the hall he did not appear to have much, if any, drink taken.

Blaney was vindictive. My father lost his post as an actor and was sent to work as a clerical officer in the Department of Posts and Telegraphs. He didn’t last long and left to work as a freelance actor in Britain. Years later my father told me what he had said to Blaney. Drink was definitely involved but I think my father would have said what he had in any case. He told the minister that his only vision of culture was his ‘arse in a duckpond in County Donegal’. Keeping with the marshy metaphors he said that as a minister Blaney was as much use as ‘a lighthouse in the Bog of Allen’.

There was uproar. My father told me it was a price well worth paying. His verdict, nearly thirty years later, was: ‘That ignorant gobshite! What would he know about culture?’

Years later Blaney would achieve notoriety when he was sacked from the cabinet amid allegations that he had been involved in smuggling arms to nationalists in Northern Ireland.

My first memory of childhood is of clouds. They are big black clouds and they sit on the roofs of the houses in Finglas West. I see them because I have run out of the house. I cannot remember why. The garden gate is tied with string. I cannot go any further, so I stand with my face pressed against the bars and watch the clouds. The bars feel cold and I press my face even closer, loving that coldness. I keep watching the clouds, wondering if they will fall from the sky, what noise they will make when they hit the ground. But the clouds just sit there. Then I hear my name being called.

‘Fergal, Fergal.’

It is my mother’s voice.

After a while she comes out and leads me back into the house.

There is silence inside. My father is upstairs. At this age I know nothing. But I can sense things. There is something about this silence that is not like other silences, not like the silence of very early morning, or the silence of a house where people are sleeping. It is the silence after an argument, as if anger has changed the pressure of the air. I have already learned to live inside my head; in my head there are ways to keep the silence at bay. I stand in the room and feel the silence for a moment and then I go deep into my head and start to dream, back to the clouds and the noise of rain, loud enough to fill the world with sound. This is how things have been from the moment I can remember.

I go to bed and stay awake as late as I can, lying in my room, listening for the sound of his homecoming: footsteps outside the front door, shuffling, a key scratching at the lock, and a voice that sings sometimes, and other times shouts, and other times is muffled, a voice being urged to quietness by my mother.

Drinking. What do you know about drinking when you are six years of age? More than you should is the quick answer. Drinking is someone changing so that their eyes are staring out from some other world to yours, flashing from happy to angry to sad, sometimes all in the same sentence; eyes that are far from you, as if behind them was a man who had been kidnapped and held prisoner; drinking is a mouth with a voice you know but cannot recognise because it is stretched and squashed, like a record played backwards, or the words falling around like children on ice, banging up against each other, careening across the evening with no direction, nothing making sense except the sound of your own heart pounding so loud you are sure every house in the street can hear it. Boom, boom, boom.

You imagine the noise travelling out of your bed and knocking on all the doors, waking up those sane, clean-living Irish families and spilling your secret. You are ashamed. Of that one thing you are certain. Shame. It becomes your second skin. You are sure other people know. Someone will have seen him come home, or heard him making a noise. They can read it in your eyes, in your silences and evasions, in the way you twitch and fidget. After nights lying awake for hours you go to school half sick for want of sleep, your mind miles away. The teacher speaks your name in Irish:

‘Are you listening, O’Cathain? Are you paying attention? Come up here and explain to the class what you were thinking about.’

‘Nothing, Bean Ui Bhanseil. Nothing.’

‘Don’t mind your nothing. What was I teaching just now? What did I read?’

‘I can’t remember. I’m sorry.’

Tabhair dom do labh. Give me your hand.

There. Now go back to your seat and pay attention. Don’t be crying like a mammy’s boy.

Other kids say that too. Mammy’s boy. They know how to get me going. A boy called Grant, a big fellow, always in trouble with the teachers, shouts at me one day: ‘Your mammy’s a pig.’ I attack him. I have no idea where the strength comes from but I go for the bastard and hurt him, until he gets over the shock and starts to hurt me. Punch, kick, punch. I am left sitting on the ground crying. Grant is right. I am my mother’s boy. I cling to her. I am her confidant.

As I get older I often sit up late with her. I have learned to make calculations. I know that if teatime passes, and homework time, and there is still no sign of him, there is a chance that my father is drinking. And if the evening news comes and goes without him I know it is a certainty. My mother corrects school homework. I watch the television. We wait. After the national anthem has played on RTE my mother switches off the television.

I have grown used to this tension and fear. It is my homeland. And here is the hardest thing to admit: I love being this boy who stays up late, this child who imagines himself as his mother’s protector, the boy who can listen to confidences, who is praised for being so mature. That’s me: Little Mr Mature. You could tell him anything.

My father always smiles when he sees me. He pulls me towards him, always gently, and I smell the smell that is half sweet and half stale, fumes of hot whiskey breath surround me and fill the room. He tells me that he loves me and he hugs me, again and again. If he is in a happy drunk state he tells stories about people he met on the way home – impossibly sentimental stories of kindnesses given and received; but if he’s angry he will curse some enemy of his at work, some actor who is conniving against him, some producer who doesn’t know his arse from his elbow. He can rage bitterly. I don’t know why sometimes he is happy and other times angry. My father has never raised his hand to me. Nor can I remember him ever being consciously cruel to me. It is his anger that scares me, the violence that takes over his voice. Through it all I keep an eye on my mother, until she signals that I should go to bed, and reluctantly I climb the stairs.

Sometimes from upstairs I hear a louder voice. It echoes up the hallway. This voice is beyond control. I keep my eyes on the lights of cars flashing their beams across the ceiling. I put my hands to my ears. Downstairs I hear the sound of my childhood splintering. Only when it is quiet, long after it is quiet, do I sleep.

It is still a few years to their separation. At this point nothing is determined. I do not sense that a sundering is close. I am not afraid that they will break up. In this Ireland families do not break up because of drink. Families like us stay together. Instead I have this fear that they will both die. It comes to me in dreams. I dream that they are killed in a car crash and I wake up crying.

CHAPTER TWO Homeland (#ulink_5cc02757-27f5-5080-9c3a-7939cc93f225)

Many young men of twenty said goodbye. On that long day, From the break of dawn until the sun was high Many young men of twenty said goodbye.

‘Many Young Men Of Twenty’, JOHN B. KEANE

I had come back to Ireland with my parents in 1961, as thousands of their fellow countrymen were heading the other way. Our people clogged the mail boats to Holyhead with their cardboard suitcases and promises of jobs on the building sites. Éamonn and Maura lived in a succession of flats and boarding houses. They had little money. My father had acting work but if he started drinking there was no money. There were days of plenty and days of nothing. By now my mother was pregnant again. Two more children would follow in the next two years. Saving money for a deposit on a house was out of the question. Eventually they were given a house by the Dublin Corporation in one of the vast new council estates being built to the west of the city, in Finglas. In those days the tenements of inner-city Dublin were being cleared and the residents moved to vast new housing estates on the fringes of the city. One nineteenth-century writer described Finglas as a village where ‘the blue haze of smoke from its cottages softened the dark background of the trees’. But by the time we arrived there there were no cottages or trees. The green fields had been turned into avenue upon avenue of concrete.

In keeping with the nationalist ethos of the Republic many of the streets on the new estates were named after heroes of rebellions against the British. Go onto any council estate in Ireland and you will find streets named after guerrilla leaders. My parents were given the keys to a two-bedroom terraced house on Casement Green, named after Sir Roger Casement.

Éamonn and Maura would have stood out among the residents of Finglas. They were neither Dubliners nor working class. Both were well educated. Most of those they lived among had grown up on the hard streets of the inner city and left school at an early age to find work. It was said then of Finglas, and not quite jokingly, that it was so tough even the Alsatians walked around in pairs.

Our next-door neighbour was Breda Thunder. At dinner time her house smelled of boiled bacon ribs and cabbage, and chips with salt and vinegar. Breda was a handsome woman with auburn hair and laughing eyes – a native Dubliner, from Charlemont Street near the Grand Canal. Her husband Liam was a thin and wiry redhead and came from Rathmines on the other side of the canal. Breda and Liam arrived on the estate a few weeks after my parents. Years later Breda told me: ‘The first time I saw you, you were standing on your own in the garden near our fence, a lovely little boy with blond hair, just standing there and smiling. That’s how I’ll always see you.’

I loved her because she seemed so fearless. You felt safe around Breda. She was the first person I knew who showed no fear when my father was drunk. Breda had grown up in tenement Dublin, on some of the toughest streets in Europe, in an atmosphere where women learned early how to deal with men who drank, and where the only dependable wage for many was the ‘shilling a day’ earned in the service of the British military. Her own father, Jamesy Harris, had served in both world wars, and her grandfather fought in the Boer War. Breda had a good soldier’s courage.

Breda and Liam had five boys and had fostered a girl – the daughter of Liam’s brother Paddy who had been killed serving with the Irish Guards in Aden. Her sons were my first playmates. They were boisterous and noisy and loyal. The neighbourhood bullies knew to give the Thunder boys a wide berth. Pick on a Thunder or on any of their friends, and you had the whole clan to deal with. Once, a young policeman collared Breda’s second youngest son, Sean, for cycling on the pavement outside her house. The child was about five, and quite obviously too young to head out onto the open road. Breda looked out the window and saw the very tall policeman haranguing her child. Seconds later she was bearing down on him:

‘Where are you from?’ she demanded.

He replied that he came from County Mayo.

This triggered an automatic resentment in Breda’s heart. She was a proud Dubliner, convinced that the city had no equal anywhere in the world and believing that visitors to the city owed a debt of respect to the natives. Any public official from County Mayo or any of the remoter rural areas would initially have been regarded with suspicion by Breda and her neighbours. Only after proving themselves as decent souls would they be welcomed. To have a culchie – a country person – even if he was a policeman, tell her son he couldn’t cycle on Dublin concrete was an appalling insult.

‘Well, fuck off back there, you big ignorant gobshite! This is my town and I won’t have some culchie in size twelve boots frightening my child.’

The policeman departed soon after, followed by a hail of abuse.

Breda’s was a house of relentless noise, a great deal of which was laughter. One of her daily trials was raising her sons from their beds and hunting them out to school. None of them liked the Christian Brothers School in Finglas; all waited for the day when they could quit and go to work, and each morning there was the same vaudeville: Breda would stand at the bottom of the stairs and roar at her sleeping boys above. When this failed to rouse them she would run upstairs and shake them out of bed. She would then go back downstairs to prepare the breakfast and school lunches. The boys merely continued to sleep where they had fallen, or crept into another bed.

I have fragmented memories of that time. I remember walking with Breda to the shops on a misty morning in winter and seeing the horses of travellers grazing on the green, the owners camped nearby under plastic sheeting and their red-haired children running out to look at us. We called them ‘the tinkers’. My father said they lost their land when Cromwell drove the Irish into Connaught.

There were other mornings, standing in the hallway of Breda’s house, when her husband Liam would stop by with a trayful of cakes from the bakery where he worked. ‘Pick any one you want,’ he would say. There were sugary doughnuts, chocolate éclairs, custard slices and thick wedges of dark cake called ‘Donkey’s Gur’. The back of Liam’s van smelled of warm bread: turnover and batch loaves, fresh from the baker in Cabra. As he drove away other kids would run after the van. ‘Mr Breadman. Mr Breadman. Gi’s a cake, will ya.’ And I remember Breda’s happiness on a weekend night, when the work of feeding and cleaning was done, and she would sit in the small front room and tell stories about her father fighting the Nazis, before switching into song: The Roses are Blooming in Picardy…

My mother told me stories about our neighbours.

Near to the shops lived a family I will call the Murphys. Joe worked in a factory and Mary cleaned offices in the city. Such work involved leaving home every morning shortly after six and rushing home in the late afternoon in time to make dinner for the family. Mary spent her life on her knees, polishing the long floors of the Royal College of Surgeons for pitiful wages. In Mary’s case, cooking was a problem. She was a devoted mother but her ignorance of all but the basic rudiments of cooking shocked Breda. There was much resort to tins and packets in Mary’s house. So Breda Thunder took it upon herself to teach Mary how to prepare roast chicken and potatoes for Sunday lunch.

The following Monday, Mary knocked on Breda’s door. The chicken and spuds had been a triumph. Mary described in detail how the chicken had been divided:

‘You know, I had a leg for Joe, a leg for Peter and a leg for myself and for Martina, there was a leg for Mick too when he came in from work, and there was even one left over to give the dog in his bowl.’

Astonished at the profusion of legs on one chicken Breda declared: ‘Are you sure it was a chicken and not a fuckin’ centipede you cooked!’

As I grew older other neighbours and their children entered my field of vision. There was a woman called Sadie Doyle who lived on the opposite side of the street. Sadie wore a fur coat and her blonde hair in a beehive. She had a family of seven crammed into a tiny council house. When she came into Breda’s house the boys would start singing a Beatles song: Sexy Sadie, what have you done? You made a fool of everyone… Sadie would make to clip them on the ear and then burst out laughing.

Like Mary and Joe and Breda and Liam, Sadie worked all hours to keep her family fed and clothed. Sadie and Breda were much less romantic in their ideas about men than my mother. Both were immensely protective of Maura. They saw her as a lost innocent who had blundered into the world of marginal choices and needed protection if she was going to survive. My mother spoke with a different accent and was clearly a child of the Irish middle classes. But Breda and Sadie were immune to resentment or class bitterness. When she came to them Maura was thin and haggard, strained with the effort of caring for the man she married and her growing family. They saw a young woman in trouble and responded in the only way they knew.

With Breda acting as childminder my mother was able to go to work. She found a job on the other side of the city at a placed called Clontarf, an old, established suburb on the shores of Dublin Bay. ‘Clontarf is where Brian Boru was killed by the Danes when the Vikings invaded Ireland,’ she told me. A big Dane called Broder came into the King’s tent and murdered him.

My mother taught English and French to boys who had no interest in either. But she was alive in a way that these boys had never known a teacher to be. She told them stories and helped them to find something they did not know they had: their better nature. The headmaster was a strict man, a man of his time and place. I met him once and he surprised me, after what I had heard about him, by taking me to the basement and opening the door onto a room where he kept a huge train set. The room was dusty, smelled of chalk and ink, and the train sped around and around, through tunnels and past mountains, like the train to my grandmother’s house in Cork. I imagined him standing there after the school had emptied watching the endless journey of his tiny locomotives, a hard lonely prisoner of Ireland in the 1960s.

Now that my mother had a job there was regular money. She was saving every month, putting by a little into a special account because she dreamed of owning a house of her own. For my mother, coming from the comfortable world she did, it was not unusual to aspire to ownership. But for her neighbours, Breda and Liam, the money they were busy saving represented an unimaginable social change. In the old Ireland people like them didn’t get to own houses. They went from generation to generation in crumbling tenements or lived in hope of a flat in one of the new tower blocks. Liam Thunder had other ideas.

Finglas was getting tougher all the time. If he kept his sons there, there was a good chance at least one of them would get into trouble. Squad cars already called at other houses in the area. The police were becoming the enemy. In the years to come parts of Finglas would become notorious for drug dealing, as cheap heroin flooded into Dublin and boys from the area would become addicts, pushers and gangsters.

My mother kept saving. I think there may also have been part of her which believed that a move might somehow change my father. Once she had saved the deposit she started hunting for houses, far away in Terenure on the south side of the city. She found a handsome redbrick on a quiet street named Ashfield Park and we moved there in the middle of the 1960s.

After Casement Green this house seemed huge to me: downstairs it had a living room, a dining room, a breakfast room and a kitchen; upstairs there were four bedrooms. I had one all to myself. Outside the room in which my parents slept there was a huge willow tree which swayed back and forth whenever the wind blew. At first it frightened me, and then my father told me that the willow was a lucky tree.

Shortly after we moved in, Breda Thunder and the boys came to visit. I remember Breda wearing a black fur coat and filling our new dining room with laughter, astonished like us at the size of the place. Not long afterwards she and Liam and the boys left Finglas too for a bright new home of their own on the western approaches to the city. For a while it looked as if all our luck was turning.

My father’s career as an actor began to blossom. By the mid-sixties he was in demand on radio, television and stage. I was about six years old when I first entered a radio studio. It was the old RTE building on Henry Street in Dublin, near the riotous noise of Moore Street market with its vegetable and flower sellers, and right next to the General Post Office – still pockmarked with bullet and shrapnel marks from the fighting of 1916.

To a child’s eye Henry Street was a deep and gloomy building which smelt of floor polish and cigarettes. In the actors’ greenroom men and women lounged on sofas and chairs mumbling to themselves as they read great sheaves of paper. These were called scripts, my father explained, and you had to learn them off by heart. The actors, producers, writers, and an army of sound engineers, turned out everything from Chekhov to one of the Republic’s first soap operas, The Kennedys of Castleross, about a family in a seaside village whose tribulations – very minor by the standards of today – kept the nation entranced for years. In one of those studios I watched, mesmerised, as my father and the other actors read their lines. Never before had I seen such stillness, or concentration. As soon as the recording was done, the actors started chatting. The spell was broken. How could they go from such magic to behaving like boring adults?

Acting was always my father’s greatest love. He committed himself totally to every performance; it tormented him of course, and criticism of any kind tore into him like a steel claw. When reviews were bad he would retreat into himself as if the words were directed at him the person and not the actor on the stage; he was a man who could never divide the actor from the self. On those days he was angry and short tempered, storming out of the house at the smallest excuse.

Luckily the bad reviews were rare. As the sixties progressed he had a string of successes. He appeared as the lead in a triumphant revival – ‘the hit of 1968’ – of Dion Boucicault’s melodrama The Shaughraun at the Abbey Theatre. Movie offers started to come in. He appeared in two American films that were made in Ireland. He started to talk about Hollywood. After all, there other Irish actors like Barry FitzGerald and Milo O’Shea who had already blazed the trail. My father’s first film appearance was inUnderground, set in France during the Second World War. There was a role for a child in this film and my father arranged an audition for me. When the day came I was taken down to the National Film Studios in County Wicklow. But I was seized by terror and ran out of the film company offices. A few months later I was again convulsed by stage fright during a school play. I knew the words but my throat went into spasm from fear. Any temptation to follow my father onto the stage disappeared in those agonising moments.

Ireland was changing now. Playwrights such as my Uncle John B. Keane and Brian Friel were writing an alternative narrative to that offered by Church and State. Éamonn and Maura relished the new atmosphere, the challenge to the old order that was being thrown up. My awareness of the wider world was shaped by my parents’ non-conformism and, in both of them, a blazing sympathy for the underdog in Irish life. One of my earliest memories is of my father inviting in a group of travelling people – the eternal outcasts of our society – and sitting them down to tea.

I doubt if he checked whether we had the food to give them, and he certainly wasn’t the person who cooked, but it was an important example for me. It was the gesture that mattered. Many other doors on our street would have been slammed in their faces. Years later, when I read Nadine Gordimer writing about apartheid in South Africa, there was a phrase which reminded me of my parents. It was the duty, said Gordimer, of every person faced with injustice to make the ‘essential gesture’. It would be different in every life. Some would go to jail for their beliefs; others would do something as small as writing a letter to their local newspaper, or signing a petition. But what gave the gesture its power was that it came from the heart.

My parents filled their lives with ‘essential gestures’. They were people of the heart. When she was teaching Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ my mother went and dug out some library books on the poet, and in the course of her research discovered that Shelley had come to Dublin to campaign on behalf of the Catholic poor. With great flair she conjured up an image of the poet, shivering on the streets of nineteenth-century Dublin, as he pressed his pamphlets on the uninterested gentry and the bemused proletariat. ‘Oh, the courage of that,’ she would say.

My mother taught English and French for forty years. She worked long hours. At night when the school day was over she would sit marking mounds of copybooks, laughing to herself at the mistakes, calling me over to read when a pupil had written something particularly good. Her work ethic was an inspiration. Long before the idea of extra-curricular activities became fashionable she was spending hours in cold school halls rehearsing her pupils through the plays of Shakespeare, or taking her senior class to art-house cinemas to watch films such as Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, and Fellini’s La Dolce Vita. I was taken along to that particular double bill, and was bored out of my mind, developing a lifelong aversion to black-and-white Scandinavian films. Years later I asked my mother why she took a young child to witness the grimness of Bergman. ‘I thought it might be good for you,’ she said, without pausing to explain why.

Troubled children were drawn to my mother. So too were the slow learners. I remember resenting the amount of time she gave to her army of timid, abused, or struggling pupils. But in a society where the idea of talking your troubles out with a therapist was hardly known, the sympathetic teacher was often the only option. Some of these pupils are still her friends today.

Maura was the second eldest of nine children, a bright, determined child. She excelled at school and went on to study English literature and French at university. She was the first member of the family to travel abroad, going to work as an au pair in France after graduating from school. At the age of eighteen she hitchhiked from France to Italy and back to Ireland, a journey of exceptional daring for a child of middle-class Ireland. My mother was her family’s rebel. She teamed up with a ‘radical’, though not by today’s standards, group of students and dated a ‘notorious’ communist, a rare species in Cork, ‘Red’ Mick O’Leary, who later went on to become Deputy Prime Minister of Ireland and signed the Sunningdale Agreement to create the first power-sharing government in Northern Ireland.

Largely her life then seemed to involve dancing to American rock and roll and walking barefoot through Cork in solidarity with the oppressed masses of the world, reading the work of people like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg and ambushing with eggs and flour the stuffy students of the Medical Department when they paraded through town. In those days the medical establishment was fiercely reactionary, dominated by conservative Catholics and paranoid about state intrusion into its private demesne. My mother and her friends were the Beats of Cork, though not likely to bring the stuffy Republic crashing to its knees.

Some strange characters floated through our home. Among the more exotic visitors in the late 1960s was a leader of the IRA. This was before the revival of the Troubles. The man was a dour character who was steering the movement away from nationalism towards Marxism. The nationalists despised him and soon afterwards the movement split. There was murderous feuding and our guest was, for a period, avoiding the bullets of his former comrades. I remember only a long night of tea drinking with the IRA boss droning on, his political lecture delivered half in Irish, half in English. A remark of my father’s has stayed with me from that night. ‘Jesus, that fellow could bore the British out of Ireland,’ he said.

My father knew many different politicians but he was never a party political person. Instead great causes appealed to him, so he would turn out to act in a play about apartheid in South Africa, or the murder of Patrice Lumbumba in the Congo. At different times he could be a romantic nationalist, a socialist visionary, a worshipper of Parnell and Collins, and sometimes all of these things at once.

In the summer of 1968 we went to London. My father had a part in the Abbey Company’s production of the George Fitzmaurice play The Dandy Dolls at the Royal Court in Sloane Square. The play and my father’s performance in particular were well received. Those are among the happiest days of my childhood memory.

We all travelled over by boat, arriving at night into a city that seemed on fire with light and roaring with noise. This was the first return to the city in which I’d been born and my parents seemed excited and happy. We stayed in a guesthouse on Ebury Street in Pimlico. There was no end of novelties. We had orange juice and bacon for breakfast, travelled on red buses and on the Tube, motored down the Thames on a riverboat and ate takeaway curries at night. A theatre critic over from Dublin asked me one day: ‘Do you know at all what a great man your father is?’ I told him I did. I was passionately proud of him. My father wasn’t drinking and seemed genuinely happy. At night he took me for short walks, my hand in his, guiding me through the night.

We had good days, my father and I. They are so precious to me now that I remember the smallest details. On my birthday in January 1971, in Dublin, he took me into town on the bus. The Christmas lights were still up, reflected on the dark Liffey and in the pools of rain along O’Connell Street. He held my hand as we walked down into Henry Street, past the hawkers back from their Christmas break, flogging off the last of the tinsel and crackers, shouting ‘apples, bananas and oranges’, and every so often I would notice someone recognising my father. Sometimes they came up and asked for his autograph. Other times they whispered to the person they were with: ‘It’s your man off the telly. Your man the actor.’

By this time Éamonn was a public figure. He was always kind to the people who asked him to sign something or who wanted to have a moment of his time. I would stand there, holding his hand, while he listened to them praising his performance in some play or other, or sharing some anecdote from their own lives.

But on the day of my birthday nobody stopped us. We were unstoppable! My father had been sober for a while now, and we strode through the city with confidence. We went to a café behind the Moore Street market. ‘You can have anything you like,’ my father said. Double burger and chips followed by doughnuts it was, then. Then we went to see the great film of the moment, Waterloo, starring Rod Steiger. I cheered when the Emperor returned from Elba and was re-united with his army. At the end of the film I wept at Napoleon’s defeat and was comforted by my father. ‘Able was I ere I saw Elba,’ he said. ‘That’s the same sentence even if you spell it backwards.’

We travelled home across the bridge over the Grand Canal and into Harold’s Cross where the road divided for Terenure and Kimmage. On the bus home I pressed close to him and he put his arm around me and told me jokes.

My memory is hungry for the happy moments. I realise now that I have hoarded them over the years. They are my version of the family silver. I remember a night around Christmas time when the car became trapped in a bog on the way to my father’s home place in Listowel. There was a heavy mist. But I wasn’t fearful. My mother was calm at the wheel. My father kept talking to keep our spirits up.

By the time we got there the lights were out in my grandmother’s house on Church Street. I staggered sleepily upstairs to bed in the footsteps of my parents. When I woke early and looked outside the street was glistening with frost and I saw the first donkeys and carts rattle past, laden with milk cans on their way to the creamery.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/fergal-keane/all-of-these-people-a-memoir/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Fergal Keane

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 493.36 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In a memoir of staggering power and candour, award-winning journalist Fergal Keane addresses his experience of wars of different kinds, some very public and others acutely personal.During his years of reporting from the world′s most savage and turbulent regions, Fergal Keane has witnessed the violence of the South African townships and the terror in Rwanda, the most extreme kinds of human behaviour, the horror of genocide and the bravery of peacekeepers faced with overwhelming odds. As one of the BBC′s leading correspondents, he recounts extraordinary encounters on the front lines. Alongside his often brutal experiences in the field, he also describes unflinchingly the challenges and demons he has faced in his personal life growing up in Ireland.Keane’s existence as a war reporter is all that we imagine: frantic filing of reports and dodging shells, interspersed with rest in bombed-out hotels and concrete shelters. Life in such vulnerable areas of the globe is emotionally draining, but full of astonishing moments of camaraderie and human bravery. And so this is also a memoir of the human connections, at once simple and complex, that are made in extreme circumstances. These pages are filled with the memories of remarkable people. At the heart of Fergal Keane′s story is a descent into and recovery from alcoholism, spanning two generations, father and son; a different kind of war, but as much part of the journey of the last twenty-five years as the bullets and bombs.