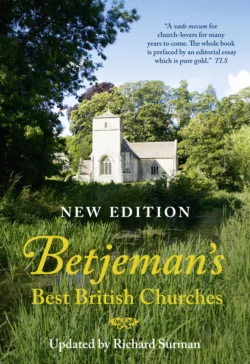

Betjeman’s Best British Churches

Richard Surman

Sir John Betjeman

A beautiful and practical up-to-date guide to over two thousand of Britain’s best parish churches.Although now most famous for his poetry, Sir John Betjeman’s great passion was churches. For over fifty years his guide, regularly updated, has been the eminent authority and the most distinguished guide to the best churches to visit.This edition, in full colour throughout and illustrated with over 350 specially commissioned photographs, covers over 2,500 of the very best churches in England, Scotland and Wales. Fully updated by bestselling author Richard Surman, this is the most complete and up to date guide to Britain’s church heritage.

BETJEMAN’S BEST BRITISH CHURCHES

UPDATED BY RICHARD SURMAN

With photographs by Michael Ellis and Richard Surman

Contents

Cover (#ud76f2760-4e04-5e88-9eaa-96c1c99248f4)

Title Page (#u54ae687b-ca04-5fcf-8b49-be5505d443bf)

How to find a Church

County Locator

PREFACE by Richard Surman (#ulink_2d0516a4-a64a-5042-911a-ac2b45aa52ac)

INTRODUCTION by Sir John Betjeman (#ulink_6415b04e-9226-511b-8f57-e9a732551bfe)

ENGLAND BY COUNTY

BEDFORDSHIRE (#ulink_b06e14df-eade-50c0-94c8-c16bd01a1b1e)

BERKSHIRE

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE

CAMBRIDGESHIRE

CHESHIRE

CORNWALL

CUMBRIA

DERBYSHIRE

DEVON

DORSET

DURHAM

ESSEX

GLOUCESTERSHIRE

HAMPSHIRE & THE ISLE OF WIGHT

HEREFORDSHIRE

HERTFORDSHIRE

KENT

LANCASHIRE, MERSEYSIDE & GREATER MANCHESTER

LEICESTERSHIRE

LINCOLNSHIRE

LONDON

GREATER LONDON

NORFOLK

NORTHAMPTONSHIRE

NORTHUMBERLAND AND TYNE & WEAR

NOTTINGHAMSHIRE

OXFORDSHIRE

RUTLAND

SHROPSHIRE

SOMERSET & BRISTOL

STAFFORDSHIRE

SUFFOLK

SURREY

SUSSEX – EAST

SUSSEX – WEST

WARWICKSHIRE & WEST MIDLANDS

WILTSHIRE

WORCESTERSHIRE

YORKSHIRE – EAST RIDING

YORKSHIRE – NORTH

YORKSHIRE – SOUTH

YORKSHIRE – WEST

WALES

SCOTLAND

THE ISLE OF MAN

THE CHANNEL ISLANDS

Glossary

Index of Architects and Artists

Index of Places

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

How to find a Church (#ulink_16317d92-4a25-5d97-81ef-1325ef029697)

This book includes Ordnance Survey (OS) and Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates to help readers locate the churches with precision.

USING THE OS COORDINATES

The OS grid references work on all the paper Ordnance Survey maps and the Ordnance Survey’s OpenData service on its website (www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk). If using the website, simply type the full grid reference into the OpenData search bar – e.g. SE966710 – which will take you directly to a map page showing the church, usually identifiable as ‘PW’ for ‘place of worship’.

If you are using an Ordnance Survey paper map, the same six-digit grid reference will work as follows:

• THE FIRST TWO LETTERS – e.g. the SE of SE966710 – refer to the Ordnance Survey’s division of Great Britain into 100 x 100 km major grid squares, each identified by two letters. On the paper maps, the letters can be seen in large lettering in the corner 1km grid squares and also where the major squares butt up to each other.

• THE FIRST TWO DIGITS – e.g. 96 – refer to the horizontal grid lines, called the ‘eastings’, which are numbered left to right on the paper maps.

• THE THIRD DIGIT – e.g. 6 – refers to the eastings grid in tenths. Thus the 6 in this example is six-tenths east of grid line 96.

• THE FOURTH AND FIFTH DIGITS – e.g. 71 – refer to the vertical grid lines, called the ‘northings’, which are numbered bottom to top on the paper maps.

• THE SIXTH DIGIT – e.g. 0 – refers to the northings grid in tenths. Thus the 0 in this example is within one-tenth north of grid line 71.

The division of tenths on the six-digit OS references in this book should be accurate to within 100 metres of the church.

USING THE GPS COORDINATES

These references give the latitude and longitude of locations in a digital format used by many car SatNav systems, mobile devices with GPS, and major online mapping applications such as Google and Bing.

Car SatNavs

First check if your SatNav allows the input of latitude and longitude / GPS coordinates. There are several reference systems in operation, so select ‘digital’ if given the option. In some SatNavs you will need to key in the full GPS coordinates with letters – e.g. 54.12669N, 0.52226W – while in others the letters may have to be selected separately.

Note that the GPS coordinates given in this book are centred on the church building itself, rather than an access point into the grounds or the nearest car park. Churches sited in remote fields, woods or parks may be some distance from the nearest public highway, and in such cases SatNavs won’t necessarily guide you to the best access point or parking place, although they should indicate where the church stands.

If your car SatNav does not offer the option to input the coordinates, we would suggest that you search for the village name and then the church name as a point of interest within the village, or, failing that, searching for ‘Church Street’ in a village often yields results!

Google Maps and Bing

Google Maps, Bing and some other online maps directly read the digital coordinates given in this book. Simply type the coordinates – e.g. 54.12669N, 0.52226W – into the map’s search bar.

Mobile phones and Other GPS Devices

Handheld devices that support GPS can read the GPS coordinates. On an iPhone, BlackBerry or Android device, for example, open the Google Maps application and type the coordinates into the search bar. Devices that use Full GPS (linking directly to satellites) are more accurate than those using Assisted GPS (via mobile phone masts).

If your device does not recognize the letters in the references, try leaving out the letters and substituting a minus sign before the longitude reference – e.g. 54.12669, -0.52226. (The minus sign is not necessary for longitude references ending in E.)

County Locator (#ulink_4164a646-ea33-555d-9d2a-729363f702e0)

COLN ST DENYS: ST JAMES THE GREAT – sunk into the picturesque Gloucestershire landscape, the church retains its Norman ground plan and tower

© Richard Surman

PREFACE by Richard Surman (#ulink_bdc53f75-e918-5dbe-8047-3df94a41ce5c)

Since John Betjeman compiled the first 1958 edition of the Collins Guide to English Parish Churches, it has become a classic of its kind, and has been reprinted several times, most notably in the two-volume Collins Pocket Guide to English Parish Churches, published in 1968, and the 1980 edition, in which the scope of the book was extended to take in churches in Wales. The background to the book is a story all of its own. To many, Sir John Betjeman was latterly the Poet Laureate, whose work was reviled and adored in equal measure. But Betjeman was many things apart from being a poet: as a young boy holidaying in Trebetherick he went church-hunting, and in adolescence, churches became a passion for him. He would always talk about his childhood impressions of buildings as being crucial in determining his later responses to architecture.

Friendships with James Lees-Milne, the noted architectural advisor to the National Trust, Betjeman’s work on the Architectural Review, where he met and formed a life-long friendship with the artist John Piper, a spell as the film critic for the Evening Standard – all these fed Betjeman’s limitless and sometimes mischievous imagination, which was equally exercised by his colourful private life.

His working life would take a different emphasis however, when he proposed the idea of a series of county guides to Jack Beddington, publicity manager of Shell-Mex BP. Beddington was known for his patronage of artists and writers, and Betjeman found himself working alongside Paul Nash and a coterie of friends to whom he handed out work on the Shell Guide series. What always characterised Betjeman’s reactions to architecture and countryside was a sense of place – the setting – as well as architectural and topographical detail. However mannered Betjeman might sometimes appear, one of his great gifts was to let landscape, architecture and art speak for themselves. After the war, Betjeman worked on many magazines, as well as writing poetry, and appearances on television became more and more regular. His presenting of the ABC of Churches programmes was a great success, not least to the crew, with whom he got on famously (although he did disconcert at least one member of the crew by taking his teddy bear Archibald Ormsby Gore wherever he went).

This new version – Betjeman’s Best British Churches – takes Betjeman’s original idea and moves it in a slightly different direction, but with great respect for his fundamental love of parish churches. The volume has much of a 21st-century feel about it – the age of satellite navigation and precision mapping have allowed us to create very precise locations for each of the churches featured herein. Betjeman would have found this odd, I’m sure, but it is our hope that in ‘modernising’ the format of the book, we might appeal to a new audience more familiar with the digital age, as well as re-invigorating those familiar with earlier versions.

There are three radical departures from previous editions. The first is that we have introduced a much stronger pictorial element: full colour photographs are used throughout the book, as are accurate and clear maps of each county. The second radical difference arises from the first: with a large number of colour illustrations, the extent of the book has had to be considerably reduced. Betjeman’s original book contained some 4,500 entries, and in some respects was a gazetteer. We decided to considerably modify this present edition, cutting down to some 2,500 entries. The criterion for retaining entries has been, wherever possible, to refer to the very simple star system that Betjeman employed in the 1968 edition, as the basis for first selection. Although the most recent 1993 edition discarded this form of rating, we have re-introduced it here, refining it so that throughout the book there is now a one- and two-star rating. Naturally there are many other churches included that were not starred in Betjeman’s 1968 edition – some of those have been revised too. There are also new churches included, and to these we have applied rating criteria that reflect those of which Betjeman would have approved.

The third radical departure from previous versions is the creation of an entirely new section for Scotland. Though Scottish religious history differs quite significantly from that of England and Wales, we believe that there is a sufficient number of fine churches in Scotland to merit a place alongside their English and Welsh counterparts.

Another distinct feature of this present book is the inclusion of several notable Roman Catholic churches: these have been selected as being of outstanding historical, architectural or artistic merit. The medieval abbey of Pluscarden in Scotland qualifies on both counts, first as the only medieval monastery in the British Isles in continuous use – barring a hiatus after the Reformation – by a Roman Catholic monastic community, and second as a centre of design and production of outstanding contemporary glass. The Church of the Immaculate Conception, Farm Street, London has an entry, based on the excellent work of A. W. N. Pugin to the altar and reredos and the chancel chapels by H. Clutton and J. F. Bentley. London’s Brompton Oratory gets an entry too; it would be remiss to ignore this extraordinary piece of Rome in London. In common with earlier editions we have also included churches in the care of the excellent Churches Conservation Trust, the Friends of Friendless Churches – especially in Wales – and English Heritage.

As regards the structure of counties, we have followed all the modern ceremonial boundaries: this has necessitated a considerable re-ordering of Yorkshire, the merging of Westmorland and Cumberland into Cumbria, changes to Berkshire and Oxfordshire and several other counties. Rutland, the country’s smallest and fiercely independent county, has been retained, whilst Huntingdonshire and the Soke of Peterborough have been brought together within Cambridgeshire. Bristol is with Somerset, and London is in two parts, Central and Greater London (the latter containing Middlesex and the inner parts of Essex, Kent and Surrey). Greater Manchester and Merseyside are together with Lancashire.

Considerable effort has gone into checking the facts about each entry, and wherever possible we have corrected errors. For errors that we have inadvertently introduced or have failed to correct, we both apologise and welcome comments.

To those people who may be disconcerted by the disappearance from this edition of their familiar churches, we ask for their forbearance, and hope that we have explained with sufficient persuasion the reasons why. Above all what we have striven to achieve is a book that captures the spirit of the earlier editions, in a 21st-century context.

A book such as this is not possible without the work of many people, not least those who have contributed to the various counties over the years. In particular I would like to thank Sam Richardson and Helena Nicholls at Collins Reference for their enthusiastic support for a long and complex project. I would also like to express my gratitude to Mike and Ros Ellis at Thameside Media: their hard and painstaking work on the planning, design, mapping, checking and photography have been essential. Their enthusiasm and expertise has taken them, I suspect, way beyond their brief. I am also very grateful to Michael Lynch, former Sir William Fraser Professor of Scottish History and Palaeography, for his eagle-eyed and helpful observations on my attempts to disentangle Scottish religious history.

Many others have contributed more indirectly – those hard-working souls that keep (some) of our fine churches open, that write the individual church guides, many of which are of a very high standard, and the various organisations, particularly the Churches Conservation Trust, the Friends of Friendless Churches, the National Churches Trust and the many county historic church trusts, all of whom work tirelessly to preserve a priceless heritage – the parish church.

Richard Surman 2011

WALPOLE ST PETER: ST PETER – the porch to the church is vaulted in a beautiful sandstone, the bosses sculpted into the sleeping forms of foals, sheep and suchlike

© Michael Ellis

INTRODUCTION by Sir John Betjeman (#ulink_d05847c5-eac0-566c-be6d-64aa9b03a30f)

PART ONE: THE OLD CHURCHES

To atheists inadequately developed building sites; and often, alas, to Anglicans but visible symbols of disagreement with the incumbent: ‘the man there is “too high”, “too low”, “too lazy”, “too interfering”’ – still they stand, the churches of England, their towers grey above billowy globes of elm trees, the red cross of St George flying over their battlements, the Duplex Envelope System employed for collections, schoolmistress at the organ, incumbent in the chancel, scattered worshippers in the nave, Tortoise stove slowly consuming its ration as the familiar 17th-century phrases come echoing down arcades of ancient stone.

Odi et amo. This sums up the general opinion of the Church of England among the few who are not apathetic. One bright autumn morning I visited the church of the little silver limestone town of Somerton in Somerset. Hanging midway from a rich-timbered roof, on chains from which were suspended branched and brassy-gleaming chandeliers, were oval boards painted black. In gold letters on each these words were inscribed:

TO GOD’S

GLORY

&

THE HONOR OF

THE

CHURCH OF

ENGLAND

1782

They served me as an inspiration towards compiling this book.

The Parish Churches of England are even more varied than the landscape. The tall town church, smelling of furniture polish and hot-water pipes, a shadow of the medieval marvel it once was, so assiduously have Victorian and even later restorers renewed everything old; the little weather-beaten hamlet church standing in a farmyard down a narrow lane, bat-droppings over the pews and one service a month; the church of a once prosperous village, a relic of the 15th-century wool trade, whose soaring splendour of stone and glass subsequent generations have had neither the energy nor the money to destroy; the suburban church with Northamptonshire-style steeple rising unexpectedly above slate roofs of London and calling with mid-Victorian bells to the ghosts on the edge of the industrial estate; the High, the Low, the Central churches, the alive and the dead ones, the churches that are easy to pray in and those that are not, the churches whose architecture brings you to your knees, the churches whose decorations affront the sight – all these come within the wide embrace of our Anglican Church, whose arms extend beyond the seas to many fabrics more.

From the first wooden church put up in a forest clearing or stone cell on windy moor to the newest social hall, with sanctuary and altar partitioned off, built on the latest industrial estate, our churches have existed chiefly for the celebration of what some call the Mass, or the Eucharist and others call Holy Communion or the Lord’s Supper.

Between the early paganism of Britain and the present paganism there are nearly twenty thousand churches and well over a thousand years of Christianity. More than half the buildings are medieval. Many of those have been so severely restored in the last century that they could almost be called Victorian – new stone, new walls, new roofs, new pews. If there is anything old about them it is what one can discern through the detective work of the visual imagination.

It may be possible to generalize enough about the parish church of ancient origin to give an impression of how it is the history of its district in stone and wood and glass. Such generalization can give only a superficial impression. Churches vary with their building materials and with the religious, social and economic history of their districts.

The Outside of the Church – Gravestones

See on some village mount, in the mind’s eye, the parish church of today. It is in the old part of the place. Near the church will be the few old houses of the parish, and almost for certain there will be an inn very near the church. A lych-gate built as a memorial at the beginning of this century indicates the entrance to the churchyard. Away on the outskirts of the town or village, if it is a place of any size, will be the arid new cemetery consecrated in 1910 when there was no more room in the churchyard.

Nearer to the church and almost always on the south side are to be found the older tombs, the examples of fine craftsmanship in local stone of the Queen Anne and Georgian periods. Wool merchants and big farmers, all those not entitled to an armorial monument on the walls inside the church, generally occupy the grandest graves. Their obelisks, urns and table tombs are surrounded with Georgian ironwork. Parish clerks, smaller farmers and tradesmen lie below plainer stones. All their families are recorded in deep-cut lettering. Here is a flourish of 18th-century calligraphy; there is reproduced the typeface of Baskerville. It is extraordinary how long the tradition of fine lettering continued, especially when it is in a stone easily carved or engraved, whether limestone, ironstone or slate. The tradition lasted until the middle of the 19th century in those country places where stone was used as easily as wood. Some old craftsman was carving away while the young go-aheads in the nearest town were busy inserting machine-made letters into white Italian marble.

ST JUST-IN-ROSELAND: ST JUST – coastal lichen and moss on one of the headstones

© Michael Ellis

The elegance of the local stone carver’s craft is not to be seen only in the lettering. In the 18th century it was the convention to carve symbols round the top of the headstone and down the sides. The earlier examples are in bold relief, cherubs with plough-boy faces and thick wings, and scythes, hour glasses and skulls and cross-bones diversify their tops. You will find in one or another country churchyard that there has been a local sculptor of unusual vigour and perhaps genius who has even carved a rural scene above some well-graven name. Towards the end of the 18th century the lettering becomes finer and more prominent, the decoration flatter and more conventional, usually in the Adam manner, as though a son had taken on his father’s business and depended on architectural pattern-books. But the tops of all headstones varied in shape. At this time too it became the custom in some districts to paint the stones and to add a little gold leaf to the lettering. Paint and stone by now have acquired a varied pattern produced by weather and fungus, so that the stones are probably more beautiful than they were when they were new, splodged as they are with gold and silver and slightly overgrown with moss. On a sharp frosty day when the sun is in the south and throwing up the carving, or in the west and bringing out all the colour of the lichens, a country churchyard may bring back the lost ages of craftsmanship more effectively than the church which stands behind it. Those unknown carvers are the same race as produced the vigorous inn signs which were such a feature of England before the brewers ruined them with artiness and standardization. They belong to the world of wheelwrights and wagon-makers, and they had their local styles. In Kent the chief effect of variety was created by different-sized stones with elaborately-scalloped heads to them, and by shroud-like mummies of stone on top of the grave itself; in the Cotswolds by carving in strong relief; in slate districts by engraved lettering. In counties like Surrey and Sussex, where stone was rare, there were many wooden graveyard monuments, two posts with a board between them running down the length of the grave and painted in the way an old wagon is painted. But most of these wooden monuments have perished or decayed out of recognition.

‘At rest’, ‘Fell asleep’, ‘Not dead but gone before’ and other equally non-committal legends are on the newer tombs. In Georgian days it was the custom either to put only the name or to apply to the schoolmaster or parson for a rhyme. Many a graveyard contains beautiful stanzas which have not found their way to print and are disappearing under wind and weather. Two of these inscriptions have particularly struck my fancy. One is in Bideford and commemorates a retired sea-captain Henry Clark, 1836. It summarizes for me a type of friendly and pathetic Englishman to be found hanging about, particularly at little seaports.

For twenty years he scarce slept in a bed;

Linhays and limekilns lull’d his weary head

Because he would not to the poor house go,

For his proud spirit would not let him to.

The black bird’s whistling notes at break of day

Used to wake him from his bed of hay.

Unto the bridge and quay he then repaired

To see what shipping up the river stirr’d.

Oft in the week he used to view the bay,

To see what ships were coming in from sea,

To captains’ wives he brought the welcome news,

And to the relatives of all the crews.

At last poor Harry Clark was taken ill,

And carried to the work house ’gainst his will:

And being of this mortal life quite tired,

He lived about a month and then expired.

The other is on an outside monument on the north wall of the church at Harefield, near Uxbridge, one of the last three country villages left in Middlesex. It is to Robert Mossendew, servant of the Ashby family, who died in 1744. Had he been a gentleman his monument would at this time have been inside the church. He was a gamekeeper and is carved in relief with his gun above this inscription.

In frost and snow, thro’ hail and rain

He scour’d the woods, and trudg’d the plain;

The steady pointer leads the way,

Stands at the scent, then springs the prey;

The timorous birds from stubble rise,

With pinions stretch’d divide the skies;

The scatter’d lead pursues the sight

And death in thunder stops their flight;

His spaniel, of true English kind,

With gratitude inflames his mind;

This servant in an honest way,

In all his actions copies Tray.

The churchyard indeed often contains cruder but more lively and loving verses than the polished tributes inscribed in marble tablets within the church to squires and peers and divines of the county hierarchy. The Dartmoor parish of Buckland Monachorum displays this popular epitaph to a blacksmith which may be found in other parishes:

My sledge and hammer both declin’d,

My bellows too have lost their wind.

My fire’s extinct, my forge decay’d,

And in the dust my vice is laid,

My coal is spent, my iron’s gone,

My nails are drove, my work is done.

Though such an epitaph can scarcely be called Christian, it is at least not an attempt to cover up in mawkish sentiment or in crematorial good taste the inevitability of death.

The Outside

The church whose southern side we are approaching is probably little like the building which stood there even two centuries before, although it has not been rebuilt. The outside walls were probably plastered, unless the church is in a district where workable stone has long been used and it is faced with cut stone known as ashlar. Churches which are ashlar-faced all over are rare, but many have an ashlar-faced western tower, or aisle to the north-east or south-east, or a porch or transept built of cut stone in the 15th century by a rich family. Some have a guild chapel or private chantry where Mass was said for the souls of deceased members of the guild or family. This is usually ashlar-faced and has a carved parapet as well, and is in marked contrast with the humble masonry of the rest of the church.

Rubble or uneven flints were not considered beautiful to look at until the 19th century. People were ashamed of them and wished to see their churches smooth on the outside and inside walls, and weather-proof. At Barnack and Earl’s Barton the Saxons have even gone so far as to imitate in stone the decorative effects of wooden construction. Plaster made of a mixture of hair or straw and sand and lime was from Saxon times applied as a covering to the walls. Only the cut stone round the windows and doors was left, and even this was lime-washed. The plaster was thin and uneven. It was beautifully coloured a pale yellow or pink or white according to the tradition of the district. And if it has now been stripped off the church, it may still be seen on old cottages of the village if any survive. The earlier the walls of a church are, the less likely they are to be ashlar-faced, for there was no widespread use of cut stone in villages until the late 14th century when transport was better, and attention which had formerly been expended on abbeys was paid to building and enlarging parish churches.

EAST SHEFFORD: ST THOMAS – plaster on exterior walls would once have been common but is now a rarity; here too is a use of many materials: brick, stone, tile and timber

© Michael Ellis

And this is the place to say that most of the old parish churches in England are building rather than architecture. They are gradual growths, as their outside walls will shew; in their construction they partake of the character of cottages and barns and the early manor house, and not of the great abbey churches built for monks or secular canons. Their humble builders were inspired to copy what was to be seen in the nearest great church. The styles of Gothic came from these large buildings, but the village execution of them was later and could rarely rise to more than window tracery and roof timbering. Even these effects have a local flavour, they are a village voluntary compared with the music played on a great instrument by the cathedral organist. Of course here and there, when the abbeys declined, a famous mason from an abbey or cathedral might rebuild the church of his native place, and masons were employed in rich wool districts of East Anglia, the Midlands and parts of Yorkshire and Devon to build large churches which really are architecture and the product of a single brain, not the humble expression of a village community’s worship. Much has been discovered about the names and work of medieval architects by Mr John Harvey in his book Gothic England and in the researches of Messrs. Salzman, and Knoop and Jones.

These outside walls on which the sun shews up the mottled plaster, the sudden warm red of an 18th-century patching of brick, the gentle contrast with the ashlar, the lime-washed tracery of the windows, the heating chimney-stack in local brick climbing up the chancel wall or the stove pipe projecting from a window, these are more often seen today in old watercolours in the local museum, or in some affectionate and ill-executed painting hanging in the vestry shewing the church ‘before restoration in 1883’. Most of our old churches have been stripped of their plaster, some in living memory. The rubble has been exposed and then too often been repointed with grey cement, which is unyielding and instead of protecting the old stones causes them to crack and flake in frosty weather, for cement and stone have different rates of expansion. To make matters worse the cement itself has been snail pointed, that is to say pointed in hard, flat lines, so that the church wall looks like a crazy pavement.

Old paintings sometimes shew the external roofs as they used to be. The church roof and chancel are scarcely distinguishable from the cottage roofs. If the original steep pitch survives, it is seen to be covered with the local tiles, stones or thatch of the old houses of the district. 15th-century and Georgian raisings or lowerings of the roof and alterations to a flatter pitch generally meant a re-covering with lead, and the original pitch may be traced on the eastern face of the tower. Victorian restorers much enjoyed raising roofs to what they considered the original pitch, or putting on an altogether new roof in the cathedral manner. The effect of those re-roofings is generally the most obviously new feature on the outside of an old church. Red tiles and patterned slates from Wales or stone tiles which continually come down because they are set at a pitch too steep for their weight, are the usual materials. Instead of being graded in size, large at the eaves and getting smaller as they reach the ridge, the stone tiles are all of the same size so that the roof is not proportioned to the walls. The ridges are usually crowned with ridge tiles of an ornamental pattern which contrast in colour and texture with the rest. The gable ends are adorned with crosses. The drainage system is prominent and there will be pipes running down the wall to a gutter. On the rain-water heads at the top of these pipes there will probably be the date of the restoration. The old way of draining a roof was generally by leaden or wooden spouts rushing out of the fearsome mouths of gargoyles and carrying the water well beyond the walls of the church into the churchyard. If the water did drip on to the walls the plaster served as a protection from damp. Butterfield, a comparatively conservative and severely practical Victorian restorer, in his report on the restoration of Shottesbrooke church (1845) remarks of the flint walls of that elegant building, ‘There are no parapets to any part of the Church, and the water has continued to drip from the eaves for five centuries without any injury to the walls.’ On the other hand the water has continued to drip from the eaves of Sir Edwin Lutyens’ fine church of St Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London, and over its Portland stone cornice with considerable injury to the brick walls in less than half a century. The nature of the wall surface, the pointing, and the means devised for draining the water clear from the wall foundation once it has reached the ground, have much to do with keeping out the damp.

Sometimes we may find on the outside walls a variety of scratches, marks and carvings. The only ones of any beauty will probably be the consecration crosses, where the Bishop anointed the walls with oil when the church was newly built. They are high up so that people would not brush them in going past. Similar crosses may be seen on stone altars inside the church. The small crosses which are cut roughly in the jambs of doorways were, according to the late E. A. Greening Lamborn, an angry antiquarian with a good prose style, probably put there not for consecration but ‘to scare away evil spirits and prevent them crossing the threshold’. There is a whole literature devoted to masons’ marks on the walls of churches, outside and in, and to the ‘scratch dials’ or ‘mass clocks’ which look like sundials lacking a gnomon, to be found on the outside south walls of many churches. The masons’ marks are triangles, diamonds, bent arrows, circles, squares and other shapes looking rather like boy scout signs, cut into ashlar in some churches, notably the large ones, and surviving where stone has not been re-tooled by the Victorians. Often they may be only scribbles. But they seem to help some antiquaries to give an exact date to buildings or portions of a building. Scratch dials or mass clocks were used generally to show the time when Mass was to be said (usually 9 a.m. in medieval England). Others are primitive clocks. But they, like the parish registers, belong to the non-visual side of church history and it is with the look of a church that this book is primarily concerned.

Finally there are on the outside of churches the gargoyles spouting water off the roof and the carved heads to be found either side of some windows and the figures in niches on tower or porch. Gargoyles can be fearsome, particularly on the north side of the church, and heads and statues, where they have survived Puritan outrage and Victorian zeal, are sometimes extremely beautiful or fantastic.

The church porch flapping with electoral rolls, notices of local acts, missionary appeals and church services (which will occupy us later) gives us a welcome. Though the powers of the parish vestry have been taken over by parish councils and local government, church doors or the porches which shelter them are often plastered with public announcements. Regularly will the village policeman nail to the church door some notice about Foot-and-Mouth Disease when the British Legion Notice Board has been denied him or the Post Office is shut. Most church porches in England are built on the south side, first as a protection for the door from prevailing south-west gales. Then they were used as places for baptism, bargains were made there, oaths sworn, and burial and marriage services conducted. Above some of them, from the 14th century onward, a room was built, usually for keeping parish chests and records. In these places many a village school was started. At first they may have been inhabited by a watchman, who could look down into the church from an internal window. In counties where stone is rare there are often elaborate wooden porches, notably in Sussex, Surrey and Essex.

ASHTON: ST JOHN THE BAPTIST – the 15th-century screens at the church have some of Devon’s best figurative panel painting

© Michael Ellis

Professor E. A. Freeman, the great Victorian ecclesiologist, thought little of a man who went up the churchyard path to the main door, which is more or less what we have done, and did not go round the whole building first. But he was an antiquary who took his churches slowly, speculated on them and did detective work about dates of extensions. On a day when the wind is not too cold and the grass not too long and wet, a walk round the outside of the church is always worth while. On the farther side, which is generally the north, there may well be extensions, a family mausoleum for instance, of which there is no sign inside the church beyond a blocked archway. Mr John Piper and I had a peculiar experience through not going round the outside of the derelict church of Wolfhamcote near Daventry in Warwickshire. The lovely building was locked, the windows smashed, and the sun was setting on its lichened stone. There was only one cottage near and we could make no one hear. So we climbed through a window in the south aisle. Bat-droppings were over rotting floors and damp stains on the ochre-plastered walls, and in the fading light we saw that the altar cloth had been raised and revealed a black tunnel with light at the end, a most peculiar thing to see beyond an altar. We approached and saw there were stairs going down under the table leading to a passage in which brass-studded coffins lay on shelves. When we went round the outside of the church we saw that beyond the east end was a Strawberry Hill Gothick extension, the mausoleum of the Tibbits family. Vestries are more usual on the north side of churches than mausolea, and very ugly most of them are, hard little stone sheds leant against the old walls. There will be almost for certain a north door blocked or bricked-up long ago, with the trace of its arch mouldings still there. There may even be a north porch. But unless the village and manor house are to the north of the church this side of the churchyard will be gloomy and its tombs will be, at the earliest, 19th century, except for a very few near the east end. And so round by the sexton’s tool-shed and the anthracite dump and the west door of the tower, we return to the south porch.

ROCK: ST PETER AND ST PAUL – like many churches, it has retained its Norman doorway while the church around it has been fully Gothicised

© Michael Ellis

Notice the stonework round the outside doors. Often it is round-headed and of Norman date, an elaborate affair of several concentric semi-circles of carved stone. It may even be the only Norman work left in the church and may originally have been the chancel arch before the chancel was enlarged and a screen put across its western end. The later medieval rebuilders respected the Norman craftsmanship and often kept a Norman door inside their elaborate porches.

There is often difficulty in opening the door. This gives the less impatient of us a chance of looking at the door itself. Either because the business of transferring the huge church lock was too difficult, or because here was a good piece of wood older than any of the trees in the parish, church doors have survived from the middle ages while the interiors on to which they open have been repaired out of recognition. The wood of the door may be carved or be decorated with old local ironwork. If it is an old door it will invariably open inwards. So first turn the iron handle and push hard. Then if the door seems to be locked, turn the handle the other way and push hard. Then feel on the wall-plate of the porch for the key. Church keys are usually six or eight inches long and easy to find. If there is no sign of the key and all vestry doors are locked, call at a house. If the path leading through the churchyard to a door in the vicarage wall is overgrown and looks unused, you may be sure the vicarage has been sold to wealthy unbelievers and there is no chance of getting the key from there. The houses to choose are those with pots of flowers in the window. Here will be living traditional villagers who even if they are chapel will probably know who it is who keeps the church key. Men are less likely to know than women, since men in villages are more rarely church-goers. Villagers are all out on Saturday afternoons shopping in the local town. Only an idiot and the dog remain behind.

The Porch and Bells

Down one step – for the churchyard will have risen round an old building – and we are in the church itself.

The practised eye can tell at a glance how severe the restoration has been, and often indeed who has done the damage. For instance almost every other church in Cornwall, beside many farther east, was restored by Mr J. P. St Aubyn late in the 19th century, and he has left his mark at the church porch in the form of a scraper of his own design, as practical and unattractive as his work. We must remember, however much we deplore it, that the most cumbersome bit of panelling bought from a Birmingham firm without regard for the old church into which it is to go, the sentimental picture for the Art Shop, the banner with the dislocated saint, the Benares ware altar vases, the brass commemorative tablet, the greenish stained-glass window with its sentimental Good Shepherd – often have been saved up for by some devout and penurious communicant. It must be admitted that spirituality and aesthetics rarely go together. ‘Carnal delight even in the holiest things,’ says Father R. M. Benson, founder of the Cowley Father ‘(habits of thought and philosophy, acquisition of knowledge, schemes of philanthropy, aesthetic propriety, influence in society) hinders the development of the Christ-life by strengthening the natural will.’ So when one is inclined to lament lack of taste and seemingly wilful destruction of beauty in a church, it is wise to remember that the incumbent, even if he be that rarity a man of aesthetic appreciation, is probably not to blame for modern blemishes to the fabric. He is primarily a missioner and he cannot offend his parishioners on so unspiritual a matter. The reader who casts his mind back to his early worship as a child will remember that a hymn board, or a brass cross or a garish window were, from his customary gazing on them Sunday after Sunday, part of his religious life. If as an older and more informed person his taste and knowledge tell him these things are cheap and hideous, he will still regret their passing with a part of him which is neither his intellect nor his learning. How much more will an uninformed villager, whose feeling always runs higher where the church is concerned than a townsman’s, cling to these objects he has known as a boy, however cheap they are. When the vicar or rector felt himself entitled to be a dictator, he could with more impunity and less offence than now, ‘restore’ the old church out of recognition. He could hack down the box-pews, re-erect a screen across the chancel, put the choir into surplices and move it from the west gallery to the chancel, and substitute a pipe organ for the old instruments. Even in those days many a disgruntled villager left the church to try his voice in chapel or to play his instrument in the old village band. It is a tribute to the hold of our church that congregations continued to use their churches after restorations in Victorian times. Perhaps the reason for the continued hold is that the more ritualistic performance of the Church Services made church more interesting. There is no doubt that Evangelicals were worried at the success of Tractarian methods. But picture your own childhood’s church whitewashed on the advice of the Diocesan Advisory Committee, your pew gone and a row of chairs in its place, the altar different, and the chancel cleared of choir-stalls and the choir non-existent as a consequence. Were it not your childhood’s church, you would consider this an improvement. One part of you may consider it an improvement despite associations, but not the other. Conservatism is innate in ecclesiastical arrangement. It is what saves for us the history of the village or town in wood and glass and metal and stone.

Let us enter the church by the tower door and climb to the ringing chamber where the ropes hang through holes in the roof. Nowhere outside England except for a very few towers in the rest of the British Isles, America and the Dominions, are bells rung so well. The carillons of the Netherlands and of Bourneville and Atkinson’s scent shop in London are not bell ringing as understood in England. Carillon ringing is done either by means of a cylinder worked on the barrel-organ and musical box principle, or by keyed notes played by a musician. Carillon bells are sounded by pulling the clapper to the rim of the bell. This is called chiming, and it is not ringing.

Bell ringing in England is known among ringers as ‘the exercise’, rather as the rearing and training of pigeons is known among the pigeon fraternity as ‘the fancy’. It is a class-less folk art which has survived in the church despite all arguments about doctrine and the diminution of congregations. In many a church when the parson opens with the words ‘Dearly beloved brethren, the Scripture moveth us in sundry places...’ one may hear the tramp of the ringers descending the newel stair into the refreshing silence of the graveyard. Though in some churches they may come in later by the main door and sit in the pew marked ‘Ringers Only’, in others they will not be seen again, the sweet melancholy notes of ‘the exercise’ floating out over the Sunday chimney-pots having been their contribution to the glory of God. So full of interest and technicality is the exercise that there is a weekly paper devoted to it called The Ringing World.

A belfry where ringers are keen has the used and admired look of a social club. There, above the little bit of looking-glass in which the ringers slick their hair and straighten their ties before stepping down into the outside world, you will find blackboards with gilded lettering proclaiming past peals rung for hours at a stretch. In another place will be the rules of the tower written in a clerkly hand. A charming Georgian ringers’ rhyme survives at St Endellion, Cornwall, on a board headed with a picture of ringers in knee-breeches:

We ring the Quick to Church and dead to Grave,

Good is our use, such usage let us have

Who here therefore doth Damn, or Curse or Swear,

Or strike in Quarrel thogh no Blood appear,

Who wears a Hatt or Spurr or turns a Bell

Or by unskilful handling spoils a Peal,

Shall Sixpense pay for every single Crime

’Twill make him careful ’gainst another time.

Let all in Love and Friendship hither come,

Whilst the shrill Treble calls to Thundering Tom,

And since bells are our modest Recreation

Let’s Rise and Ring and Fall to Admiration.

Many country towers have six bells. Not all these bells are medieval. Most were cast in the 17th, 18th or 19th centuries when change-ringing was becoming a country exercise. And the older bells will have been re-cast during that time, to bring them into tune with the new ones. They are likely to have been again re-cast in modern times, and the most ancient inscription preserved and welded on to the re-cast bell. Most counties have elaborately produced monographs about their church bells. The older bells have beautiful lettering sometimes, as at Somerby, and South Somercotes in Lincolnshire, where they are inscribed with initial letters decorated with figures so that they look like illuminated initials from old manuscripts interpreted in relief on metal. The English love for Our Lady survived in inscriptions on church bells long after the Reformation, as did the use of Latin. Many 18th- and even early 19th-century bells have Latin inscriptions. A rich collection of varied dates may be seen by struggling about on the wooden cage in which the bells hang among the bat-droppings in the tower.

Many local customs survive in the use of bells. In some places a curfew is rung every evening; in others a bell is rung at five in the morning during Lent. Fanciful legends have grown up about why they are rung, but their origins can generally be traced to the divine offices. The passing bell is rung differently from district to district. Sometimes the years of the deceased are tolled, sometimes the ringing is three strokes in succession followed by a pause. There are instances of the survival of prayers for the departed where the bell is tolled as soon as the news of the death of a parishioner reaches the incumbent.

Who has heard a muffled peal and remained unmoved? Leather bags are tied to one side of the clapper and the bells ring alternately loud and soft, the soft being an echo, as though in the next world, of the music we hear on earth.

I make no apology for writing so much about church bells. They ring through our literature, as they do over our meadows and roofs and few remaining elms. Some may hate them for their melancholy, but they dislike them chiefly, I think, because they are reminders of Eternity. In an age of faith they were messengers of consolation.

The bells are rung down, the ting-tang will ring for five minutes, and now is the time to go into Church.

The Interior Today

As we sit in a back pew of the nave with the rest of the congregation – the front pews are reserved for those who never come to church – most objects which catch the eye are Victorian. What we see of the present age is cheap and sparse. The thick wires clamped on to the old outside wall, which make the church look as though the vicar had put it on the telephone, are an indication without that electric light has lately been introduced. The position of the lights destroys the effect of the old mouldings on arches and columns. It is a light too harsh and bright for an old building, and the few remaining delicate textures on stone and walls are destroyed by the dazzling floodlights fixed in reflectors from the roof, and a couple of spotlights behind the chancel arch which throw their full radiance on the brass altar vases and on the vicar when he marches up to give the blessing. At sermon time, in a winter evensong, the lights are switched off, and the strip reading-lamp on the pulpit throws up the vicar’s chin and eyebrows so that he looks like Grock. A further disfigurement introduced by electrical engineers is a collection of meters, pipes and fuses on one of the walls.

If a church must be lit with electricity – which is in any case preferable to gas, which streaks the walls – the advice of Sir Ninian Comper might well be taken. This is to have as many bulbs as possible of as low power as possible, so that they do not dazzle the eye when they hang from the roof and walls. Candles are the perfect lighting for an old church, and oil light is also effective. The mystery of an old church, however small the building, is preserved by irregularly placed clusters of low-powered bulbs which light service books but leave the roof in comparative darkness. The chancel should not be strongly lit, for this makes the church look small, and all too rarely are chancel and altar worthy of a brilliant light. I have hardly ever seen an electrically lit church where this method has been employed, and we may assume that the one in which we are sitting is either floodlit or strung with blinding pendants whose bulbs are covered by ‘temporary’ shades reminiscent of a Government office.

(#ulink_b3da99e3-c66a-519f-a110-9e7af3450018) I have even seen electric heaters hung at intervals along the gallery of an 18th-century church and half-way up the columns of a medieval nave.

Other modern adornments are best seen in daylight, and it is in daylight that we will imagine the rest of the church. The ‘children’s corner’ in front of the side altar, with its pale reproductions of water-colours by Margaret W. Tarrant, the powder-blue hangings and unstained oak kneelers, the side altar itself, too small in relation to the aisle window above it, the pale stained-glass figure of St George with plenty of clear glass round it (Diocesan Advisory Committees do not like exclusion of daylight) or the anaemic stained-glass soldier in khaki – these are likely to be the only recent additions to the church, excepting a few mural tablets in oak or Hopton Wood stone, much too small in comparison with the 18th-century ones, dotted about on the walls and giving them the appearance of a stamp album; these, thank goodness, are the only damage our age will have felt empowered to do.

The Interior in 1860

In those richer days when a British passport was respected throughout the world, when ‘carriage folk’ existed and there was a smell of straw and stable in town streets and bobbing tenants at lodge gates in the country, when it was unusual to boast of disbelief in God and when ‘Chapel’ was connected with ‘trade’ and ‘Church’ with ‘gentry’, when there were many people in villages who had never seen a train nor left their parish, when old farm-workers still wore smocks, when town slums were newer and even more horrible, when people had orchids in their conservatories and geraniums and lobelias in the trim beds beside their gravel walks, when stained glass was brownish-green and when things that shone were considered beautiful, whether they were pink granite, brass, pitchpine, mahogany or encaustic tiles, when the rector was second only to the squire, when doctors were ‘apothecaries’ and lawyers ‘attorneys’, when Parliament was a club, when shops competed for custom, when the servants went to church in the evening, when there were family prayers and basement kitchens – in those days God seemed to have created the universe and to have sent His Son to redeem the world, and there was a church parade to worship Him on those shining Sunday mornings we read of in Charlotte M. Yonge’s novels and feel in Trollope and see in the drawings in Punch. Then it was that the money pouring in from our empire was spent in restoring old churches and in building bold and handsome new ones in crowded areas and exclusive suburbs, in seaside towns and dockland settlements. They were built by the rich and given to the poor: ‘All Seats in this Church are Free.’ Let us now see this church we have been describing as it was in the late 1860s, shining after its restoration.

Changed indeed it is, for even the aisles are crowded and the prevailing colours of clothes are black, dark blue and purple. The gentlemen are in frock coats and lean forward into their top hats for a moment’s prayer, while the lesser men are in black broad-cloth and sit with folded arms awaiting the rector. He comes in after his curate and they sit at desks facing each other on either side of the chancel steps. Both wear surplices: the Rector’s is long and flowing and he has a black scarf round his shoulders: so has the curate, but his surplice is shorter and he wears a cassock underneath, for, if the truth be told, the curate is ‘higher’ than the rector and would have no objection to wearing a coloured stole and seeing a couple of candles lit on the altar for Holy Communion. But this would cause grave scandal to the parishioners, who fear idolatry. Those who sit in the pews in the aisles where the seats face inward, never think of turning eastwards for the Creed. Hymns Ancient and Modern has been introduced. The book is ritualistic, but several excellent men have composed and written for it, like Sir Frederick Ouseley and Sir Henry Baker, and Bishops and Deans. The surpliced choir precede the clergy and march out of the new vestry built on the north-east corner of the church. Some of the older men, feeling a little ridiculous in surplices, look wistfully towards the west end where the gallery used to be and where they sang as youths to serpent, fiddle and bass recorder in the old-fashioned choir, before the pipe organ was introduced up there in the chancel. The altar has been raised on a series of steps, the shining new tiles becoming more elaborate and brilliant the nearer they approach the altar. The altar frontal has been embroidered by ladies in the parish, a pattern of lilies on a red background. There is still an alms dish on the altar, and behind it a cross has been set in stone on the east wall. In ten years’ time brass vases of flowers, a cross and candlesticks will be on a ‘gradine’ or shelf above the altar. The east window is new, tracery and all. The glass is green and red, shewing the Ascension – the Crucifixion is a little ritualistic – and has been done by a London firm. And a smart London architect designed all these choir stalls in oak and these pews of pitch-pine in the nave and aisles. At his orders the new chancel roof was constructed, the plaster was taken off the walls of the church, and the stone floors were taken up and transformed into a shining stretch of red and black tiles. He also had that pale pink and yellow glass put in all the unstained windows so that a religious light was cast. The brass gas brackets arc by Skidmore of Coventry. Some antiquarian remains are carefully preserved. A Norman capital from the old aisle which was pulled down, a pillar piscina, a half of a cusped arch which might have been – no one knows quite what it might have been, but it is obviously ancient. Unfortunately it was not possible to remove the pagan classical memorials of the last century owing to trouble about faculties and fear of offending the descendants of the families commemorated. The church is as good as new, and all the medieval style of the middle-pointed period – the best period because it is in the middle and not ‘crude’ like Norman and Early English, or ‘debased’ like Perpendicular and Tudor. Nearly everyone can see the altar. The Jacobean pulpit has survived, lowered and re-erected on a stone base. Marble pulpits are rather expensive, and Jacobean is not wholly unfashionable so far as woodwork is concerned. The prevailing colours of the church are brown and green, with faint tinges of pink and yellow.

Not everyone approved of these ‘alterations’ in which the old churches of England were almost entirely rebuilt. I quote from Alfred Rimmer’s Pleasant Spots Around Oxford (c. 1865), on the taking down of the body of Woodstock’s classical church.

‘Well, during the month of July I saw this church at Woodstock, but unhappily, left making sketches of it till a future visit. An ominous begging-box, with a lock, stood out in the street asking for funds for the “restoration”. One would have thought it almost a burlesque, for it wanted no restoration at all, and would have lasted for ever so many centuries; but the box was put up by those “who said in their hearts, Let us make havoc of it altogether”. Within a few weeks of the time this interesting monument was perfect, no one beam was left; and now, as I write, it is a “heap of stones”. Through the debris I could just distinguish a fine old Norman doorway that had survived ever so many scenes notable in history, but it was nearly covered up with ruins; and supposing it does escape the general melee, and has the luck to be inserted in a new church, with open benches and modern adornments, it will have lost every claim to interest and be scraped down by unloving hands to appear like a new doorway. Happily, though rather late in the day, an end is approaching to these vandalisms.’

The Church in Georgian Times

See now the outside of our church about eighty years before, in, let us say, 1805, when the two-folio volumes on the county were produced by a learned antiquarian, with aquatint engravings of the churches, careful copper-plates of fonts and supposedly Roman pieces of stone, and laborious copyings of entries in parish rolls. How different from the polished, furbished fane we have just left is this humble, almost cottage-like place of worship. Oak posts and rails enclose the churchyard in which a horse, maybe the Reverend Dr Syntax’s mare Grizzel, is grazing. The stones are humble and few, and lean this way and that on the south side. They are painted black and grey and the lettering on some is picked out in gold. Two altar tombs, one with a sculptured urn above it, are enclosed in sturdy iron rails such as one sees above the basements of Georgian terrace houses. Beyond the church below a thunderous sky we see the elm and oak landscape of an England comparatively unenclosed. Thatched cottages and stone-tiled farms are collected round the church, and beyond them on the boundaries of the parish the land is still open and park-like, while an unfenced road winds on with its freight of huge bonnetted wagons. Later in the 19th century this land was parcelled into distant farms with significant names like ‘Egypt’, ‘California’, ‘Starveall’, which stud the ordnance maps. Windmills mark the hill-tops and water-mills the stream. Our church to which this agricultural world would come, save those who in spite of Test Acts and suspicion of treachery meet in their Dissenting conventicles, is a patched, uneven-looking place.

Sympathetic descriptive accounts of unrestored churches are rarely found in late Georgian or early Victorian prose or verse. Most of the writers on churches are antiquarians who see nothing but ancient stones, or whose zeal for ‘restoration’ colours their writing. Thus for instance Mr John Noake describes White Ladies’ Aston in Worcestershire in 1851 (The Rambler in Worcestershire, London, Longman and Co., 1851). ‘The church is Norman, with a wooden broach spire; the windows, with two or three square-headed exceptions, are Norman, including that at the east end, which is somewhat rare. The west end is disgraced by the insertion of small square windows and wooden frames, which, containing a great quantity of broken glass, and a stove-pipe issuing therefrom impart to the sacred building the idea of a low-class lodging house.’ And writing at about the same time, though not publishing until 1888, the entertaining Church-Goer of Bristol thus describes the Somerset church of Brean:

‘On the other side of the way stood the church – little and old, and unpicturesquely freshened up with whitewash and yellow ochre; the former on the walls and the latter on the worn stone mullions of the small Gothic windows. The stunted slate-topped tower was white-limed, too – all but a little slate slab on the western side, which bore the inscription:

JOHN GHENKIN

Churchwarden

1729

Anything owing less to taste and trouble than the little structure you would not imagine. Though rude, however, and old, and kept together as it was by repeated whitewashings, which mercifully filled up flaws and cracks, it was not disproportioned or unmemorable in aspect, and might with a trifling outlay be made to look as though someone cared for it.’

Such a church with tracery ochred on the outside may be seen in the background of Millais’ painting The Blind Girl. It is, I believe, Winchelsea before restoration. Many writers, beside Rimmer, regret the restoration of old churches by London architects in the last century. The despised Reverend J. L. Petit, writing in 1841 in those two volumes called Remarks on Church Architecture, illustrated with curious anastatic sketches, was upbraided by critics for writing too much by aesthetic and not enough by antiquarian standards.

He naturally devoted a whole chapter to regretting restoration. But neither he nor many poets who preceded him bothered to describe the outside appearance of unrestored village churches, and seldom did they relate the buildings to their settings. ‘Venerable’, ‘ivy-mantled’, ‘picturesque’ are considered precise enough words for the old village church of Georgian times, with ‘neat’, ‘elegant’ or ‘decent’ for any recent additions. It is left for the Reverend George Crabbe, that accurate and beautiful observer, to recall the texture of weathered stone in The Borough, Letter II (1810):

But ’ere you enter, yon bold tower survey

Tall and entire, and venerably grey,

For time has soften’d what was harsh when new,

And now the stains are all of sober hue;

and to admonish the painters:

And would’st thou, artist! with thy tints and brush

Form shades like these? Pretender, where thy brush?

In three short hours shall thy presuming hand

Th’ effect of three slow centuries command?

Thou may’st thy various greens and greys contrive

They are not lichens nor light aught alive.

But yet proceed and when thy tints are lost,

Fled in the shower, or crumbled in the frost

When all thy work is done away as clean

As if thou never spread’st thy grey and green,

Then may’st thou see how Nature’s work is done,

How slowly true she lays her colours on . . .

With the precision of the botanist, Crabbe describes the process of decay which is part of the beauty of the outside of an unrestored church:

Seeds, to our eye invisible, will find

On the rude rock the bed that fits their kind:

There, in the rugged soil, they safely dwell,

Till showers and snows the subtle atoms swell,

And spread th’ enduring foliage; then, we trace

The freckled flower upon the flinty base;

These all increase, till in unnoticed years

The stony tower as grey with age appears;

With coats of vegetation thinly spread,

Coat above coat, the living on the dead:

These then dissolve to dust, and make a way

For bolder foliage, nurs’d by their decay:

The long-enduring ferns in time will all

Die and despose their dust upon the wall

Where the wing’d seed may rest, till many a flower

Show Flora’s triumph o’er the falling tower.

WILLEN: ST MARY – a Classical church of the 1670s by Robert Hooke, it points the way to the Georgian interiors of the following century

© Michael Ellis

Yet the artists whom Crabbe admonishes have left us better records than there are in literature of our churches before the Victorians restored them. The engravings of Hogarth, the water-colours and etchings of John Sell Cotman and of Thomas Rowlandson, the careful and less inspired records of John Buckler, re-create these places for us. They were drawn with affection for the building as it was and not ‘as it ought to be’; they bring out the beauty of what Mr Piper has called ‘pleasing decay’; they also shew the many churches which were considered ‘neat and elegant’.

It is still possible to find an unrestored church. Almost every county has one or two.

The Georgian Church Inside

There is a whole amusing literature of satire on church interiors. As early as 1825, an unknown wit and champion of Gothic published a book of coloured aquatints with accompanying satirical text to each plate, entitled Hints to Some Churchwardens. And as we are about to enter the church, let me quote this writer’s description of a Georgian pulpit: ‘How to substitute a new, grand, and commodious pulpit in place of an ancient, mean, and inconvenient one. Raze the old Pulpit and build one on small wooden Corinthian pillars, with a handsome balustrade or flight of steps like a staircase, supported also by wooden pillars of the Corinthian order; let the dimensions of the Pulpit be at least double that of the old one, and covered with crimson velvet, and a deep gold fringe, with a good-sized cushion, with large gold tassels, gilt branches on each side, over which imposing structure let a large sounding-board be suspended by a sky-blue chain with a gilt rose at the top, and small gilt lamps on the side, with a flame painted, issuing from them, such Pulpits as these must please all parties; and as the energy and eloquence of the preacher must be the chief attraction from the ancient Pulpit, in the modern one, such labour is not required, as a moderate congregation will be satisfied with a few short sentences pronounced on each side of the gilt branches, and sometimes from the front of the cushion, when the sense of vision is so amply cared for in the construction of so splendid and appropriate a place from which to teach the duties of Christianity.’

And certainly the pulpit and the high pews crowd the church. The nave is a forest of woodwork. The pews have doors to them. The panelling inside the pews is lined with baize, blue in one pew, red in another, green in another, and the baize is attached to the wood by brass studs such as one may see on the velvet-covered coffins in family vaults. Some very big pews will have fire-places. When one sits down, only the pulpit is visible from the pew, and the tops of the arches of the nave whose stonework will be washed with ochre, while the walls will be white or pale pink, green or blue. A satire on this sort of seating was published by John Noake in 1851 in his book already quoted:

O my own darling pue, which might serve for a bed,

With its cushions so soft and its curtains of red;

Of my half waking visions that pue is the theme,

And when sleep seals my eyes, of my pue still I dream.

Foul fall the despoiler, whose ruthless award

Has condemned me to squat, like the poor, on a board,

To be crowded and shov’d, as I sit at my prayers,

As though my devotions could mingle with theirs.

I have no vulgar pride, oh dear me, not I,

But still I must say I could never see why

We give them room to sit, to stand or to kneel,

As if they, like ourselves, were expected to feel;

’Tis a part, I’m afraid, of a deeply laid plan

To bring back the abuses of Rome if they can.

And when SHE is triumphant, you’ll bitterly rue

That you gave up that Protestant bulwark – your pew.

The clear glass windows, of uneven crown glass with bottle-glass here and there in the upper lights, will shew the churchyard yews and elms and the flying clouds outside. Shafts of sunlight will fall on hatchments, those triangular-framed canvases hung on the aisle walls and bearing the Arms of noble families of the place. Over the chancel arch hang the Royal Arms, painted by some talented inn-sign artist, with a lively lion and unicorn supporting the shield in which we may see quartered the white horse of Hanover. The roofs of the church will be ceiled within for warmth, and our boxed-in pew will save us from draught. Look behind you; blocking the tower arch you will see a wooden gallery in which the choir is tuning its instruments, fiddle, base viol, serpent. And on your left in the north aisle there is a gallery crowded under the roof. On the tiers of wooden benches here sit the charity children in their blue uniforms, within reach of the parish beadle who, in the corner of the west gallery, can admonish them with his painted stave.

The altar is out of sight. This is because the old screen survives across the chancel arch and its doors are locked. If you can look through its carved woodwork, you will see that the chancel is bare except for the memorial floor slabs and brasses of previous incumbents, and the elaborate marble monument upon the wall, by a noted London sculptor, in memory of some lay-rector of the 18th century. Probably this is the only real ‘work of art’ judged by European standards in the church. The work of 18th-century sculptors has turned many of our old churches into sculpture galleries of great interest, though too often the Victorians huddled the sculptures away in the tower or blocked them up with organs. No choir stalls are in the chancel, no extra rich flooring. The Lord’s Table or altar is against the east wall and enclosed on three sides by finely-turned rails such as one sees as stair balusters in a country house. The Table itself is completely covered with a carpet of plum-covered velvet, embroidered on its western face with IHS in golden rays. Only on those rare occasions, once a quarter and at Easter and Christmas and Whit Sunday when there is to be a Communion service, is the Table decked. Then indeed there will be a fair linen cloth over the velvet, and upon the cloth a chalice, paten and two flagons all of silver, and perhaps two lights in silver candlesticks. On Sacrament Sundays those who are to partake of Communion will leave their box-pews either at the Offertory Sentence (when in modern Holy Communion services the collection is taken), or at the words ‘Ye that do truly and earnestly repent you of your sins, and are in love and charity with your neighbours’, and they will be admitted through the screen doors to the chancel. They will have been preceded by the incumbent. Thereafter the communicants will remain kneeling until the end of the service, as many as can around the Communion rails, the rest in the western side of the chancel.

ALTARNUN: ST NONNA – painted panels with biblical texts and images became popular from the 17th century; these from Cornwall hang either side of the high altar

© Michael Ellis

The only object which will be familiar from the Victorian church is the font, still near the entrance to the church and symbolical of the entrance of the Christian to Christ’s army. Beside the font is a large pew whose door opens facing it. This is the christening pew and here the baby, its parents and the god-parents wait until after the second lesson, when the incumbent will come forward to baptize the child in the presence of the congregation. Some churches had Churching pews where mothers sat.

Our churches were, as Canon Addleshaw and Frederick Etchells have pointed out in The Architectural Setting of Anglican Worship, compartmented buildings. So they remained from 1559 (Act of Uniformity) until 1841 onwards when Tractarian ideas about the prominence of the altar, the frequent celebration of Holy Communion and adequate seating for the poor – for the population had suddenly increased – caused a vital replanning of churches. What we see in 1805 is a medieval church adapted to Prayer Book worship. The object of having the Prayer Book in our own language was not so doctrinal and Protestant, in the Continental sense, as is often supposed, but was to ensure audible and intelligible services. The compartments of the building were roughly three. There is the font and christening pew which form a Baptistry. There is the nave of the church with the pews facing the pulpit which is generally half-way down the church against one of the pillars, and the nave is used for Matins, Litany and Ante-Communion. Some of the larger churches have one end of an aisle or a transept divided off with the old screens which used to surround a Chantry chapel in this part. This the parson might use for weekday offices of Matins and Evensong when the congregation was small and there was no sermon.

The lime-washed walls form a happy contrast with the coloured baize inside the box-pews, the brown well-turned Stuart and Georgian wood-work and the old screens, the hatchments which hang lozenge-shaped on the wall above family pews, and the great Royal Arms in the filled-in tympanum of the chancel arch. Behind the Royal Arms we may see faintly the remains of a medieval painting of the Doom, the Archangel Michael holding the balance, and some souls going to Heaven on one side of him, others to Hell on the other side. In other parts of the church, too, the pale brick-red lines of the painting which once covered the church may be faintly discernible in sunlight. Mostly the walls will be whitewashed, and in bold black and red, with cherubs as decorative devices, will be painted admonitory texts against idolatry. The Elizabethan texts will be in black letters; the later and less admonitory Georgian ones will be in the spacious Roman style which we see on the gravestones in the churchyard. In the Sanctuary on either side of the altar are the Lord’s Prayer and the Commandments painted in gold letters on black boards, and perhaps Moses and Aaron flank these, also painted on boards by a local inn-sign painter. An oil painting of the Crucifixion or The Deposition of our Lord or some other scriptural subject may adorn the space above the altar table. Far more people could read than is generally supposed; literacy was nearly as rife as it is today. There was not the need to teach by pictures in the parish church that there had been in the middle ages.

The lighting of the church is wholly by candles. In the centre of the nave a branched brass candelabrum is suspended by two interlocking rods painted blue, the two serpent heads which curl round and interlock them being gilded. In other parts of the church, in distant box-pews or up the choir gallery, light is from single candles in brass sconces fixed to the woodwork. If the chancel is dark, there may be two fine silver candlesticks on the altar for the purpose of illumination. But candles are not often needed, for services are generally in the hours of daylight, and the usual time for a country evensong is three o’clock in the afternoon, not six or half-past six as is now the custom.

Outside the church on a sunny Sunday morning the congregation gathers. The poorer sort are lolling against the tombstones, while the richer families, also in their best clothes, move towards the porch where the churchwardens stand with staves ready to conduct them to their private pews. The farmworkers do not wear smocks for church, but knee breeches and a long coat and shoes. Women wear wooden shoes, called pattens, when it is wet, and take them off in the porch. All the men wear hats, and they hang them on pegs on the walls when they enter the church.

How still the morning of the hallowed day!

Mute is the voice of rural labour, hushed

The ploughboy’s whistle, and the milkmaid’s song.

The scythe lies glittering in the dewy wreath

Of tedded grass, mingled with fading flowers,

That yester morn bloomed waving in the breeze.

Sounds the most faint attract the ear, – the hum

Of early bee, the trickling of the dew,

The distant bleating, midway up the hill.

With dove-like wings, Peace o’er yon village broods:

The dizzying mill-wheel rests; the anvil’s din

Hath ceased; all, all around is quietness.

Less fearful on this day, the limping hare

Stops, and looks back, and stops, and looks on man

Her deadliest foe. The toilworn horse, set free,

Unheedful of the pasture, roams at large;

And as his stiff unwieldly bulk rolls on,

His iron-armed hoofs gleam in the morning ray.

So the Scottish poet James Graham begins his poem The Sabbath (1804). All this island over, there was a hush of feudal quiet in the country on a Sunday. We must sink into this quiet to understand and tolerate, with our democratic minds, the graded village hierarchy, graded by birth and occupation, by clothes and by seating in the church. It is an agricultural world as yet little touched by the machines which were starting in the mills of the midlands and the north. The Sabbath as a day of rest and worship touched all classes. Our feeblest poets rose from bathos to sing its praises. I doubt if Felicia Hemens ever wrote better than this, in her last poem (1835), composed less than a week before she died.

How many blessed groups this hour are bending,

Through England’s primrose meadow paths, their way

Towards spire and tower, midst shadowy elms ascending,

Whence the sweet chimes proclaim the hallowed day:

The halls from old heroic ages grey