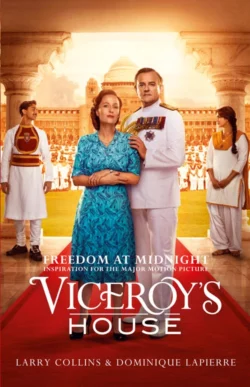

Freedom at Midnight: Inspiration for the major motion picture Viceroy’s House

Dominique Lapierre и Larry Collins

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Историческая литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 996.84 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The electrifying story of India’s struggle for independence, told in this classic account (first published in 1975) by two fine journalists who conducted hundreds of interviews with nearly all the surviving participants – from Mountbatten to the assassins of Mahatma Gandhi.This edition does not include illustrations.On 14 August 1947 one-fifth of humanity claimed their independence from the greatest empire history has ever seen. But 400 million people were to find that the immediate price of freedom was partition and war, riot and murder. In this superb reconstruction, Collins and Lapierre recount the eclipse of the fabled British Raj and examine the roles enacted by, among others, Mahatma Gandhi and Lord Mountbatten in its violent transformation into the new India and Pakistan.This is the India of Jawaharlal Nehru, heart-broken by the tragedy of the country’s division; of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, a Moslem who drank, ate pork and rarely entered a mosque, yet led 45 million Moselms to nationhood; of Gandhi, who stirred a subcontinent without raising his voice; of the last viceroy, Mountbatten, beseeched by the leaders of an independent India to take back the powers he’d just passed to them.