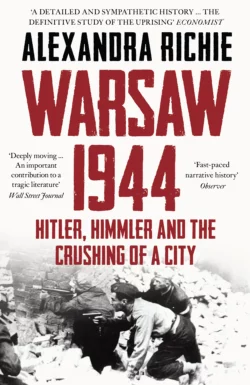

Warsaw 1944: Hitler, Himmler and the Crushing of a City

Alexandra Richie

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Книги о войне

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1552.95 ₽

Статус: Нет в наличии

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The dramatic story of the Warsaw Uprising, one of the last major battles of World War II, in which the Poles fought off German troops and police, street by street, for sixty-three days.In autumn 1944, German troops and police entered Warsaw to deport its inhabitants. Though the war was now all but lost, the demolition of Warsaw remained part of the Nazi racial plan of ′cleansing′ central Europe for future German settlement. In the first five days alone, 40,000 human beings were shot, thrown out of windows, burned alive or trampled in a frenzied killing spree. But, to Himmler′s surprise, the Poles did not give in. The Warsawians were well organized and fought valiantly. With the entire population behind it, the Uprising, which was originally expected to last less than a week, held out for sixty-three days. Finally, faced by a vastly superior force, the resistance was gradually crushed. More than 250,000 people had been killed and 85 per cent of Warsaw had been destroyed.Today Warsaw is again a bustling metropolis. Poland is a member of NATO, a member of the European Union, and its partnership with Germany is remarkably close. But scars remain: on virtually every street corner, small memorials commemorate the dead.In her compellling account of the Uprising, Alexandra Richie puts the battle of Warsaw in its rightful place within the context of the Second World War. Using previously unpublished documents and photographs, she weaves the events of the battle and the experience of the soldiers and civilians as they fought street by street into a wider political, social and military context, incorporating views of Poles trapped within the city as well as Germans and Russians who witnessed the events. By examining the Warsaw Uprising in light of the Churchill-Roosevelt-Stalin negotiations over the fate of post-war Europe, Richie examines why it has rightly been called the first battle of the Cold War.