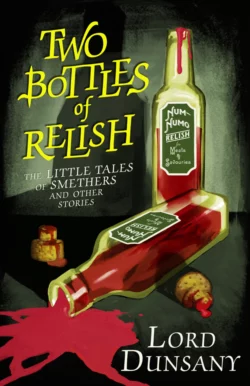

Two Bottles of Relish: The Little Tales of Smethers and Other Stories

Lord Dunsany

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1089.58 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Lord Dunsany mixes reality with fantasy in this forgotten collection of modern detective stories. Some are macabre, others have a lighter and more amusing touch, but every story stimulates the imagination and reveals the acknowledged master of the short story at his very best.SMETHERS is a travelling salesman for Numnumo, who make a relish for meats and savouries. He shares a flat with an Oxford graduate called Linley, who fancies himself as a detective and to whom Scotland Yard is inclined to turn if they encounter a particularly challenging mystery. When a pretty young girl disappears and her lodger is suspected of murdering her, two bottles of Numnumo relish are the only clues, and Smethers is sent to gather more information . . .Amongst the hundreds of fantasy stories for which the Irish dramatist, poet and writer Lord Dunsany became deservedly famous there was one solitary little book of detective stories. Selected by Ellery Queen as an ‘unequivocal keystone’ in the history of crime writing, this quirky collection is a mixture of the masterful and the macabre, a book that lovers of detective stories and tales of the unexpected will want to savour.